- Matthew Thorsen

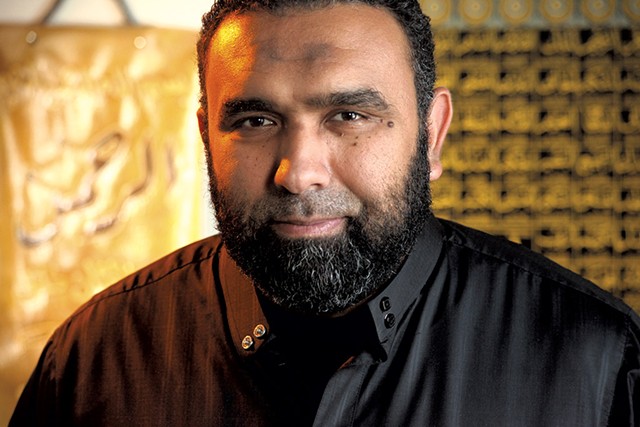

- Imam Islam Hassan

On a Sunday afternoon in June at the Islamic Society of Vermont's mosque in Colchester, eight boys and girls sat cross-legged on a plush red carpet, each holding a copy of the Koran. They listened attentively as Imam Islam Hassan explained the rules of the Koran memorization competition that would be held in a few weeks to mark the end of the Islamic fasting month of Ramadan.

"What do [the winners] get?" asked a girl, grinning.

"The memorization of the Koran is the prize," pointed out a parent, who sat within earshot.

"There will be a prize," the Egyptian-born imam assured his student. He turned to the Koran app on his iPad. "All right, we'll read 10 more verses."

Such scenes have been commonplace since Imam Islam was hired in 2011 as the first full-time imam — meaning "leader" — of this inclusive community mosque. It has grown by leaps and bounds since its founding 22 years ago. But that era is approaching a close. On May 26, the eve of Ramadan, Imam Islam announced that he and his family would be moving to Ohio at the end of June.

The news shocked many members. "I was very sad when I heard that," said Hamed Camdzic, a Bosnian American who goes to the mosque regularly. He organizes his work schedule as a Green Mountain Transit driver so he can attend Friday midday prayers, which Muslim men are required to perform together. "He's a very nice person. He taught us many things," Camdzic said of the imam.

"I feel like an orphan," said Nausheen Azhar. The South Burlington resident and her sons have attended classes taught by the imam.

According to the 38-year-old imam, who lived in Minnesota previously, "It was a combination of things that made us decide to go. We figured out what's best for us and ... our two daughters," he said. On July 15, he'll assume his new position as the imam of the Islamic Center of Cleveland.

According to Taysir Al-Khatib, president of ISVT and one of its founding members, the imam's decision didn't come as a surprise. "We know there's a time for everything. He did his dues," he said. "He wants to try something else; I don't blame him."

Regardless, everyone agrees that the maturation of the Islamic community in Vermont has been linked to Imam Islam's personal and professional development. "[To say] that this imam had nothing to do with what the [mosque] is today would be complete falsehood, because we saw it change," declared Azhar.

The Islamic community in the Green Mountain State is arguably one of the smallest in the country. Farhad Khan, who has twice served as ISVT's president, estimates that Vermont has about 4,000 Muslim residents.

There was no organization like ISVT when Khan moved to Vermont from New York City in October 1993. One of the first things he did in his new home, he recalled, was look up "Abdul," "Ahmad" and "Mohamed" in the phone book, hoping to locate Muslim families. He found about 10, he recalled. Most were families of IBM employees, one of whom organized the first Friday prayer at his house in Essex. Soon the families started to think seriously about starting an Islamic society.

The ISVT was founded in 1995. Though that coincided with the arrival of Muslim refugees from Bosnia, the burgeoning community still lacked resources. With no physical space of their own, Muslims prayed on Fridays at the Chapel of Saint Michael Archangel at Saint Michael's College. They didn't have an imam, so the men took turns giving sermons and leading prayers. "I got books to learn," Al-Khatib recalled. "We had no other choice. We felt the responsibility."

Another important task the founding members had to take on was performing funeral rites. Khan still remembers the first Muslim — a Bosnian accident victim — whom he helped bury 20 years ago in Bristol. "We had a book to see what we [should] do next, how do we wash the body," Khan said. It was January 1997 and "freezing cold ... [but] we wanted to shovel the dirt," he continued. "To this day, we still talk about it." Khan is now a selectman in Middlebury.

In 1999, ISVT bought out a computer service store located at 182 Hegeman Avenue in Colchester. The Bosnians raised most of the money to set up Vermont's first mosque in the building. "They were the driving force, because they were passionate about getting a [mosque]," explained Khan. A couple of years later, the Islamic community swelled further with the arrival of refugees from Somalia, Iraq and Burma. The Somalis would later start their own small mosque in Winooski.

- Matthew Thorsen

- Imam Islam Hassan (far right) with his students

As the community grew, ISVT leadership thought it was time to hire a full-time imam. Though the elders had stepped up to perform important rites and invited speakers from time to time, "we needed someone with a grasp of Islamic knowledge to lead the community," Khan said.

Moroccan native Houda Musanovic moved to Vermont in 2002. She said not having an imam was a "struggle." "People would have questions, and they didn't know who to go to, especially women who have to go through a divorce," the dental assistant recalled. Many also had questions on how to pay zakat, the giving of obligatory alms to the poor and needy, Musanovic added.

"We either would look for online resources, or we would wait for a visiting guest speaker and ask those questions," Khan recalled.

Not all members were convinced that ISVT would benefit from the guidance of an imam. "There are some people who are set in their ways ... They think an imam is going to bring a narrow, one-sided view," explained Khan.

Sunni Muslims generally follow one of four schools of understanding and practicing Islamic law. Because the Islamic community in Vermont is so diverse, however, a strict implementation of one particular school would marginalize segments of the population.

South Burlington resident Azhar recalled experiencing such conflicts during her youth in the United Arab Emirates. She didn't like going to her local mosque, she said, because the other congregants would always correct her posture during prayer. "People were pinching me everywhere," she recalled. Azhar, who was born in Pakistan, follows the Hanafi school, while the other women, she noted, followed the Maliki school.

Hiring an imam was a "courageous decision" that involved "a lot of commitment and money," said Khan. Some of the bigger mosques, he noted, can afford to pay an imam an annual salary of about $70,000 and provide a four-bedroom house. ISVT cannot offer such a package; most of the organization's income comes from weekly donations, which average $300 in total, and membership fees. "It's an ongoing effort to make money," Khan added.

In Minnesota, the future Imam Islam was "working casual jobs," while leading prayers when the main imam wasn't around, teaching at the local Islamic school and giving lessons on the Koran. In August 2010, ISVT invited him to lead tarawih, extra night prayers that Muslims perform during Ramadan.

He officially became imam of ISVT in 2011. Azhar, who hadn't been attending Friday prayers when the imam arrived, said she felt compelled to return after she heard positive feedback from her peers about his sermons.

GMT driver Camdzic said he saw "a lot of progress" in the community after Imam Islam joined ISVT. The imam held classes for adults and children, led prayers and taught at the Weekend Islamic School. He groomed male teens to lead tarawih. He conducted funeral rites, urged mourners not to neglect their daily prayers and did a lot of family counseling behind the scenes.

The imam was also approachable in other areas, Fatuma Bulle noted. When the Burlington College alumna wrote a dissertation titled "Muslim Women's Rights and the Hijab," the imam took the time to review her work. "He corrected me on a lot of things I didn't know," Bulle said. A member of the faculty was impressed with the imam's knowledge and asked if he would be willing to work with the college, she added.

In 2014, ISVT set out on a mission to raise $750,000 to buy the other two-thirds of its building in Colchester. Musanovic was skeptical. "Personally, I didn't think it was going to happen," she admitted.

Imam Islam rebuffed suggestions from some members of the community that the mosque take out a bank loan; usury is forbidden in Islam. Instead, he traveled out of state to raise funds. "If it was not for him and all the hard work of the community, we would not [be successful]," said Musanovic.

Al-Khatib estimated that 20 percent of the money raised came from out-of-state contributors.

Many ISVT members credit Imam Islam with fostering good relations with people of other faiths and with community partners including the Burlington Police Department. Rabbi James Glazier of Temple Sinai in South Burlington echoed their sentiments. The imam, according to Glazier, "appreciates the pluralistic society we live in." The imam and his family had visited the synagogue on a Friday night to participate in the Sabbath, the rabbi added.

Jacob Bogre, executive director of the nonprofit Association of Africans Living in Vermont, noted that the imam has been willing to talk to communities that engage in early marriages about the importance of education, especially for young women. "We will miss him," he said.

Vermont's reputation as a rural state could be a barrier in the search for a new imam. "Somebody has to be brave enough to come here," Khan said. But the small Islamic community offers a good training ground for a relatively inexperienced imam, he noted. "If you work in a place like this for five or six years [and] you get enough experience, you're bound to get [other] offers."

Al-Khatib said the search to find a new imam is already under way. The successful candidate will need to have memorized the Koran, possess a good understanding of the different schools of thought, and be able to counsel families, give sermons and lead prayers, he said.

But the most important quality the candidate will require is patience, Al-Khatib stressed: "Patience is No. 1, because we are very diverse. He has to be an imam for everybody, [like] Brother Islam was."

Comments (2)

Showing 1-2 of 2

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.