- Marc Nadel

Robin Sumner arrived 10 minutes early, set up her lawn chair and waited for Molly Gray to speak. The 59-year-old drug and alcohol counselor had heard about the Richmond community forum through Gray's campaign newsletter, which she signed up for while researching candidates. But unlike some of the 25 people fanned out around the stage that September evening, Sumner was not one of Gray's avid supporters.

"I wanted to see her in person," Sumner said from behind a face mask that depicted Rosie the Riveter. "I wanted to hear what she had to say — now that she's here."

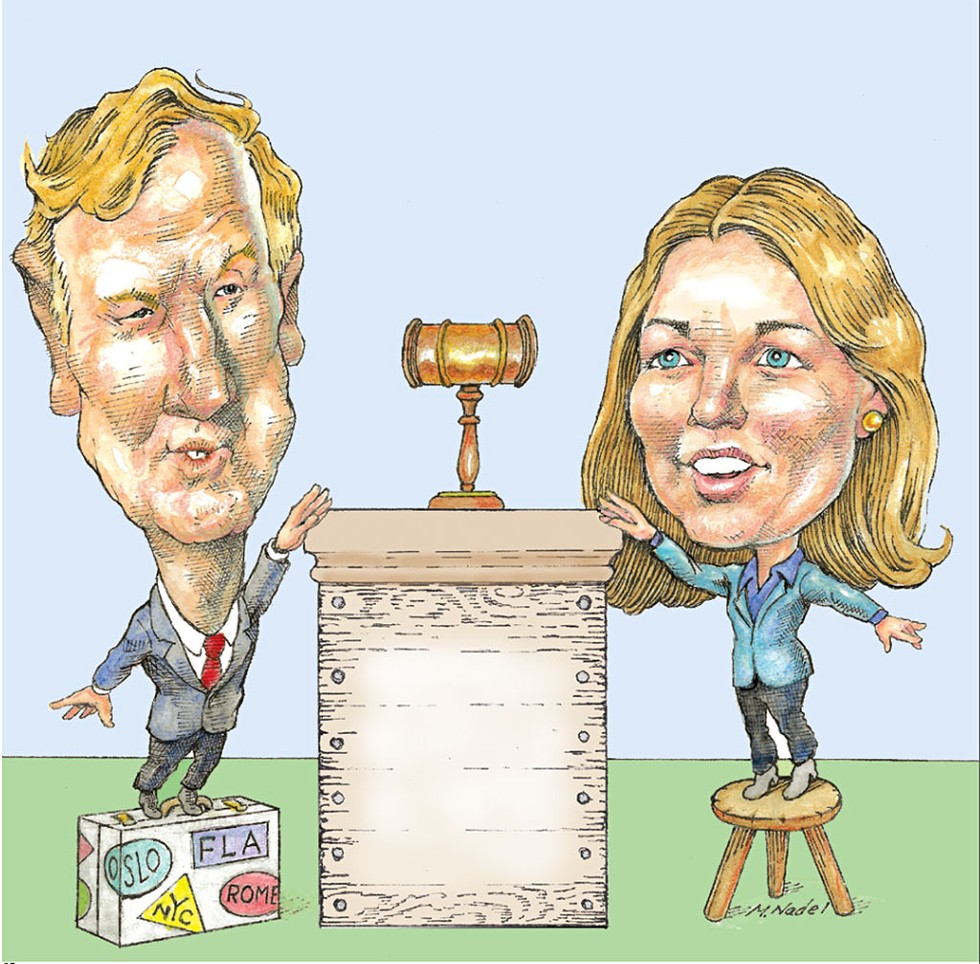

"Here"is the campaign to become Vermont's next lieutenant governor, the most competitive statewide race this cycle. Gray, a 36-year-old prosecutor in the Vermont Attorney General's Office, emerged from a crowded Democratic primary last month with a chance to become only the fourth woman ever to hold Vermont's No. 2 office. Standing in her way is Scott Milne, a 61-year-old Republican from Pomfret who runs his family's namesake travel agency and has twice before unsuccessfully campaigned for statewide office.

Sumner knew little about either candidate. Her sister is a fan of Gray's, and she was more familiar with Milne; his parents, who ran Milne Travel before him, hooked her up with some "great deals" when she used to book trips as an undergraduate student, she said. Neither connection is strong enough to earn her vote.

"I'm the type of Vermonter who usually votes people out, not in," she explained.

It is voters like Sumner, who have not made up their minds, that will likely sway the election. A recent poll conducted by Vermont Public Radio and Vermont PBS found that Gray holds a slim 35 to 31 percent advantage over Milne, within the poll's 4 percent margin of error. In other words, it is a virtual tie, suggesting that whichever candidate has more success wooing the undecided voters will prevail.

Gray and Milne have vastly different visions for the next two years.

Milne jumped into the race on May 28, months after the coronavirus pandemic struck, and says the next lieutenant governor must prioritize the survival of Vermont's small businesses. He argues that only he has the experience necessary. "We have got to stabilize Main Street," he told Seven Days earlier this month.

Gray is thinking bigger. She says Vermont's future hinges on solving its demographic crisis, a point she emphasizes by citing statistics that show deaths outpace births in a majority of counties. That, along with Vermont's struggles in retaining young people, has made it one of the grayest states in the country.

To reverse this trend, Gray wants the state to invest in childcare, broadband expansions and paid family leave, arguing that those programs and services are the only way Vermont can "keep a generation home and bring a generation here."

"This campaign is about mirroring back to Vermonters this moment we're in and how we can transform our future to meet those needs," said Gray, who announced her candidacy in late January.

Both candidates know they would have little power if elected, given that the lieutenant governor's only real duties are to preside over the Vermont Senate as its president, cast rare tie-breaking votes, help determine legislators' committee assignments, and step in if the governor is out of the state — or dies. But they also recognize that while the role lacks executive might, it provides invaluable exposure. The office may be a glorified soapbox, but it's a tall one, and the lieutenant governor generally avoids blame for initiatives that fall short. It can also serve as a useful stepping-stone — just ask former LGs such as Gov. Phil Scott.

For typical voters, however, picking whom to support is often a far less complex affair. Most want someone they agree with or, short of that, someone they can trust. For Sumner, the litmus test is simple.

"I don't need somebody just banging the gavel," she said. "I really want stuff to get done."

Farm to Statehouse?

- Luke Awtry

- Molly Gray speaking in Richmond

Gray has been working on her campaign full time since taking an unpaid leave in May from the Attorney General's Office. The pandemic has made traditional outreach efforts difficult, but she has managed to fill her schedule with business stops, honk-and-waves, and community forums.

She did all three during one busy afternoon this month, zipping back and forth between Richmond and Waterbury. She brought her newly hired scheduler, Hazel Brewster, a 23-year-old University of Vermont graduate, and Samantha Sheehan, a 32-year-old who left her communications job at Vermont Businesses for Social Responsibility to run the campaign.

Gray's first stop of the afternoon was Conant's Riverside Farms in Richmond. She hopped out of her car and slid into the passenger seat of a Bobcat 3400 utility terrain vehicle driven by Alison Kosakowski Conant, whose husband, Ransom, is a sixth-generation farmer. After securing this reporter in the Bobcat's bed, they set off rumbling through the 1,000-acre farm, crossing West Main Street into an expansive field near Interstate 89 where gourds, squash and pumpkins grew.

Gray was raised on her parents' vegetable and dairy farm in Newbury and has made her rural upbringing a central theme of her campaign. She peppered her guide with questions about the Richmond farm operation and the broader dairy industry. "Round bale or corn silage?" she asked as they rolled past a large red barn that had been renovated a few years ago with the help of state funding. "What do you think is the future of dairy?" she later asked, before steering the conversation toward internet access and childcare, two of her top priorities.

The conversation was unlikely to win Gray any votes; Kosakowski Conant was backing Gray well before the tour. But it was part of the candidate's effort to appeal to rural voters, whose voices she has promised to bring into Montpelier.

"If the pandemic could show us anything, it's that we are changing the way we access government," she told Kosakowski Conant, referring to how legislative floor debates and committee hearings have been streamed online for the first time.

Before heading out, Gray posed for a photo with Kosakowski Conant in front of the historic barn; the image was up on Gray's Twitter feed by the time she had settled in for her next stop at SunCommon in Waterbury.

There, she met with owners Duane Peterson and James Moore, who explained how they grew their business over the last decade into one of the largest community solar providers in Vermont. Gray jotted down notes in a turquoise journal and frequently asked questions about their business practices and how solar could become more accessible. Her attentiveness left an impression.

"She's just incredibly direct," Moore told Seven Days after the meeting. "'Tell me what's going on and what are the issues.' She wants to really understand and is curious, so that was neat to see. You don't always see that in political candidates or elected officials who stop by here. They just want to talk rather than listen."

Inside SunCommon's warehouse, Amy Lavery was waiting excitedly for Gray's arrival. The 45-year-old warehouse assistant only knew Gray from her campaign commercials but wanted to see if she got that "shock" people feel when meeting someone they know from television. "She looks like we could have graduated together," Lavery said, in a way that made it clear that was a good thing.

As she toured the facility, Gray eventually spotted Lavery and her coworker. She introduced herself and asked Lavery to explain what she does. "This is what I've been waiting for!" Gray said as she heard about the nuts and bolts of the operation.

Their interaction lasted only a few minutes, but it was enough for Lavery. "She's got the energy to do it," she said as Gray continued on her tour. "I mean, she just proved it to me here.

"I'm glad I haven't done my mail-in ballot yet," Lavery added.

Gray was met with the same enthusiasm back in Richmond for a late afternoon sign-waving event, where several members of the UVM College Democrats joined in.

"To see women in office, when we want to be in office at some point, is just so empowering," said 18-year-old Maeve Donnelly.

"Especially in Vermont," added Sierra Hayes, an 18-year-old Waterbury native who noted the Green Mountain State's spotty track record of electing women to the top levels of government.

Third Time's the Charm?

- Jeb Wallace-brodeur

- Scott Milne

Milne comes from a long line of politicians. In 1938, his grandfather became the first Barre Republican since reconstruction to be elected to the legislature. A cousin was secretary of state. Both his parents served in the Vermont House.

When he brings up his family, as he often does, Milne almost always mentions how his mother, a Republican, lost her House seat because she voted in favor of the groundbreaking bill to legalize same-sex civil unions in 2000. Marion Milne supported the measure despite wide opposition from her constituents, a principled stand that would end her political career.

"I will not be silenced by prejudice and fear," she declared from the House floor. Her words would be remembered nearly two decades later during a ceremony on the Statehouse lawn commemorating the historic vote.

Marion died just two months before the 2014 election. Her son keeps her old stone nameplate on his desk.

Scott Milne fancies himself an old-fashioned, moderate Republican, cut from the same cloth as the late U.S. senator George Aiken and, more recently, Gov. Scott. He has called U.S. Sen. Susan Collins (R-Maine) his political lodestar. After reluctantly swearing off Donald Trump in 2016 following the release of the "grab them by the..." tape, Milne has continued to disavow his party's president. He has said he plans to write in former Vermont governor Jim Douglas for the White House — the same choice he made in 2016.

Despite his family's political roots, Milne seems almost averse to the demands of a traditional campaign. In his mind, there are two types of politicians: those who will interrupt your dinner and those who won't. He is proudly the latter.

"If somebody looks at me like they want me to say hello, I say hello," he explained. "If they're looking like they want to have dinner, I let them have dinner."

That ethos defined his two previous bids for office. In both his 2014 near-defeat of Democratic governor Peter Shumlin and his less competitive race against Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) two years later, Milne raised little money, held few events and operated with a skeleton crew of volunteers.

Milne says he is following the same guiding principle this election, but recent developments show he senses real opportunity — and that he's upped his campaign strategy.

For starters, Milne has surrounded himself with an ensemble of well-known Republicans with proven track records in Vermont. Sen. Corey Parent (R-Franklin), a rising star in the state GOP, is managing the campaign. Mike Donohue, the party’s former Chittenden County chair, is working as Milne's press secretary. Jim Barnett, a former aide to governor Douglas and the late U.S. senator John McCain, is volunteering as a consultant.

Milne has also received an enthusiastic endorsement from Scott. In a digital ad released shortly after the primary, the governor declared: "As we face new challenges and disruptions to our economy caused by this pandemic, we need someone with Scott's experience as a problem solver and innovator in the lieutenant governor's office."

And after Milne previously struggled to earn support from the national scene, at least one group is convinced he is a worthy cause. Last week, the Republican State Leadership Committee launched a $200,000 ad campaign on Milne's behalf, calling him the partner that Scott needs to "get Vermont back to work." The money instantly leveled the playing field, erasing the three-to-one fundraising advantage — $281,000 to $90,000 — that Gray had enjoyed thanks to a lengthy donor list featuring many business owners, renewable energy advocates, fellow attorneys and top Democratic officials.

"The expectation of success breeds success," Douglas said, regarding why Milne seems to be getting broader support this time around. "People see him as a very credible candidate, so a lot more people are willing to devote some time and energy to his race."

Even Milne seems to view himself as a much stronger candidate now. Explaining his argument against Shumlin, whose second term had been crippled by a disastrous rollout of Vermont Health Connect, he said, "It was a referendum on: Are you sick of what's going on? Give me a shot."

His message this time around? "We're in a pile of shit. You want some help getting through it? I'm the guy," he said.

That was more or less the pitch former Barre City mayor Thom Lauzon made on Milne's behalf earlier this month after running into the candidate and this reporter during a walk down North Main Street.

"I'd recognize that gaggly mother anywhere!" Lauzon said as a way of greeting Milne. He implored Seven Days to be nice to the candidate because "we're gonna need people like this guy" — those who understand business — in the coming years.

Indeed, Milne's supporters consistently tout his business background as the main reason he would make the better LG, even though, beyond reforming Act 250 and several modest tax credit proposals, he has not really detailed how it is that he would help businesses survive. For example, asked at a recent debate whether he would support the state giving ailing businesses more financial assistance, Milne dodged the question, saying only that he believes there is a need for more funding from the federal government. He later told Seven Days that Milne Travel has not received any federal or state COVID-19 relief aid.

Still, the very fact that Milne understands business seems good enough to his supporters.

Lauzon, a real estate developer and trained accountant who, along with his wife, donated $4,160 to Milne's campaign, said he is deeply concerned that the next two years could spell doom for many businesses that are hanging by a thread. "It's just going to be a long winter," he said to Milne, adding that his "optimistic" guess is that one in every six businesses will go under because of the virus.

"And if it comes back—" Milne ventured.

"Don't even fucking say that," Lauzon said, half joking. "Shut up. Say that again, I'll slap you.

"No, seriously," he continued. "I don't even know, I don't even think — that would be so awful. I really try not to even think about it."

Milne, however, can't help but think about a return of COVID-19. When he is not on the campaign, he is focused on his business, which has suffered mightily under the pandemic's constraint. He sold the majority share of his travel agency to a national firm, Altour, in 2016 but remained on as president. While he has been through two economic downturns before — after the travel business came to a halt in the wake of 9/11, and then again during the 2009 recession — neither resulted in layoffs.

The same can't be said for the pandemic. His agency — which operates nine offices across Vermont, New Hampshire, New York and Maine — recently closed down a location in White River Junction. About a third of its 80 employees have taken a voluntary furlough, and the rest are working 30 hours a week.

Despite the hits, Milne doesn't seem concerned that the agency will go under. In fact, he believes it will benefit in the long run, due largely to the fact that many others in the travel industry will not. "It's not really the way you want to gain market share, but if you can survive through this, you can come out of it stronger than ever," he said.

The same could be true for so many other businesses around the state, he said. But first, they need to survive. "What kind of state we're gonna be 10 years from now has a lot to do with what happens over the next two years," Milne said.

Voting Fights

- Jeb Wallace-brodeur

- Molly Gray

Two days after the August primary, more than a dozen Democrats gathered on the Statehouse lawn for a press conference meant to show that they had set aside any hard feelings from the campaign.

The two gubernatorial candidates who lost to Lt. Gov. David Zuckerman seemed to have gotten the memo. Former education secretary Rebecca Holcombe and attorney Patrick Winburn took turns at the "unity" press conference stumping for the Progressive/Democrat. They described him as the best chance at furthering some of the Democratic priorities that Scott had vetoed during his four-year tenure and urged their supporters to rally behind him.

"We were running a relay race," Holcombe said, calling out to Winburn in the crowd. "And now we're handing the baton to David."

If Gray's competitors felt the same way, they didn't show it. All three — Sen. Debbie Ingram (D-Chittenden), activist Brenda Siegel and Senate President Pro Tempore Tim Ashe (D/P-Chittenden) — spent more time talking about each other than their newly minted nominee, offering only the thinnest of congratulations. None endorsed Gray or urged their supporters to consider voting for her.

"I want to congratulate Molly Gray on her win in the Democratic primary," was all Siegel mustered before heaping praise on Ashe and Ingram for their years of service in the legislature.

"I congratulate Molly Gray on winning the confidence of the majority of the members of our party and wish her the best in the general election," Ingram said, only after thoroughly complimenting Siegel and Ashe.

Ashe, whose dozen years in the Senate, including the last four as its leader, had made him the early favorite to succeed Zuckerman, offered the most convincing support for Gray. "[She] ran a fantastic campaign, earned the victory, and I want to congratulate her and wish her very well going into the general election," he said.

It was no big surprise that, just two days after the bruising primary, the candidates were not shouting Gray's name from the rooftops. The newcomer's rapid ascent in the Democratic party had clearly rubbed some of her competitors the wrong way, making her the target of stinging criticisms during the final weeks before the primary.

Ingram fueled questions about whether the 15 months when Gray lived in Switzerland between 2017 and 2018 made her ineligible to serve as lieutenant governor under a constitutional requirement that Vermont LGs must have "resided in this State four years next preceding the day of election." She and Siegel also attacked Gray over her voting record after it was revealed that Gray had not cast ballots in the four national elections between 2008 and 2018.

Yet it soon became clear that the lack of enthusiasm was a harbinger of the simmering discontent pockets of Democrats felt toward their nominee. Last week, that dissatisfaction burst into the open when Ingram declared she would finally endorse someone in the race: Milne.

"I have been a lifelong Democrat, and I'm still a Democrat," Ingram told reporters on the lawn of the First Unitarian Universalist Society of Burlington. "[But] I believe that Mr. Milne is the best person for this important position at this time."

According to Ingram, it was not Gray's voting record or any specific policy difference but rather her lack of life experience that swayed her decision.

"Although I am committed to supporting the advancement of women in our political system, the position of lieutenant governor is too important to decide solely on the basis of sex rather than the many other characteristics necessary for the job," Ingram said. "In my opinion, Mr. Milne's qualities in other respects matter more than electing a woman."

Ingram's distaste with the primary's result was no secret. A week afterward, she penned an op-ed in the Brattleboro Reformer that argued the media had unfairly anointed Gray and Ashe as the only two real contenders, overlooking her because she is a lesbian and Siegel because she is a low-income single mother. But her defection still shocked many Democrats.

Some saw her decision as petty. Others called it a betrayal. Others still criticized her for engaging in the same type of gatekeeping that has long discouraged more women from seeking higher office.

On Twitter, Holcombe described feeling "mystisad."

"Mystification that Ingram did this and sadness that an elected woman leader's tool of choice to take down another woman candidate is a sexist trope," she wrote.

While Ingram is the most notable prominent Democrat to publicly rebuke Gray, she is not the only member of the party to do so. Rep. Linda Joy Sullivan (D-Dorset), a moderate, announced last week that she, too, is backing Milne. The decision was less of a surprise: Sullivan unexpectedly broke ranks to vote against the effort to override Scott's veto of a paid family leave bill earlier this year, effectively killing the top Democratic priority.

Perhaps more significant are the reservations that some Democratic voters harbor about Gray's candidacy due in large part to her voting record.

Julie Cunningham, a lifelong Democrat who lives in Brattleboro, is executive director of Families First, a nonprofit organization that helps children with special needs and their families. As a Black woman, Cunningham said, she is "interested and invested" in seeing more women in politics. But while she believes that Gray is "very accomplished," she said she "cannot stop thinking" about the votes Gray skipped.

"Especially in light of everything that's happening right now, and the passing of the honorable John Lewis, who called our right to vote sacred and the most important nonviolent action we can take," she said of the late U.S. representative from Georgia.

Cunningham took particular offense at Gray's attempts to blame missing the 2016 election on the challenges of voting while abroad, given that "so many Black and brown people — marginalized people who have an incredibly difficult time voting" — still manage to do so.

At a debate last week, Gray falsely claimed that she "proudly voted for Hillary Clinton in 2016 but was unable to have my vote counted because I was serving overseas." Her campaign later clarified that she had misspoken and that her ballot was never cast.

That someone with such a poor participation record now wants to fill the state's No. 2 elected office has left Cunningham and her friends "scratching our heads," she said. Cunningham has ruled out voting for Milne but may consider writing in someone else's name, she said.

Even some Democrats who plan to vote for Gray can't seem to shake the frustration of her primary win.

Mary Ellen Manock, who helps run Flip the Vote Champlain Valley, a group of activists that seeks to prop up Democratic candidates in swing states, said she was upset by how Gray came "waltzing in" with a poor voting record and questions about her residency status and defeated someone such as Ashe, who had spent a dozen years working to further Vermont issues.

Gray had received the backing of top Vermont Democrats she had met while working for U.S. Rep. Peter Welch's (D-Vt.) 2006 campaign, as well as from mega-donor Jane Stetson, longtime Leahy campaign manager Carolyn Dwyer, and a slew of current and former Leahy staffers.

"It was just frustrating that the Democratic machine could make this happen," Manock said.

Manock went to Ashe after the primary and suggested he wage a write-in campaign. He demurred, but her frustrations remained, so much so that she would later vent about Gray in a letter to members of her women's book club. Among them: Madeleine Kunin, Vermont's only female governor and one of Gray's mentors.

Gray owned up to her lackluster voting record after it became public over the summer, saying in interviews that she was "not proud" of it.

She told Seven Days that she should not be disqualified from holding elected office because of "mistakes" that she made in her twenties and said the only thing she can do at this point is to "be honest, acknowledge that no candidate is perfect — that's my imperfection — and then work to try to get as many people excited and engaged in participating in our future as possible."

And recognizing that it would likely surface in her race with Milne, she preemptively brought it up at a solo press conference after the Democratic unity event and again acknowledged her lapse before calling on her opponent to run a race focused on the issues.

Milne's campaign, however, delighted in twisting the knife after Gray hosted an event commemorating the centennial anniversary of women's suffrage.

"Suddenly, [Gray] thinks her vote is important enough that she should cast some of her first as our lieutenant governor and president of the Senate," blasted Janet Metz, chair of the Vermont Republican Women's Coalition, who was serving as Milne's campaign coordinator at the time. "This is the epitome of privilege and entitlement. If you didn't care enough to cast a ballot when it only counted for one person, don't expect Vermont to reward you with the power to vote for the rest of us." (Shortly after Metz released this statement, she left the campaign because, according to Milne, she disagreed with his public denunciation of President Trump.)

Milne had initially kept a distance from the attacks, relying on his campaign manager to do his bidding. But he told Seven Days earlier this month that he believed Democrats who voted early for Gray, only to later learn about her voting record, are feeling "buyer's remorse." He then went on the offensive at a debate last week, asking her why voters should trust her to cast votes as their LG when she "hasn't really taken ownership of voting."

"You don't have a record of being an engaged citizen until you want to be an engaged lieutenant governor," Milne said, while referring to himself as a "consistent voter."

A day later, a left-leaning super PAC shot back on Gray's behalf, accusing Milne of lying about his own voting record. In a press release, the Alliance for a Better Vermont Fund attached a graphic that showed he missed votes in two presidential primaries (2008 and 2012) and four state primaries (2008, 2010, 2012 and 2018), as well as the 2010 general election.

"After seeing the debate last night, I was very infuriated by the hypocrisy," said Ashley Moore, executive director of the alliance. "I decided it would be a good time to essentially say, 'Hey, this is the pot calling the kettle black.'"

Milne's campaign refuted some of Moore's claims on Monday, disclosing an email from the Pomfret town clerk that said his electronic voting record did not tell the whole story. Rather, Clerk Becky Fielder wrote, a review of her office's paper records showed that the Republican had actually voted in four of the seven elections that the PAC claimed he skipped. (She said she did not have any paper records for 2008.)

Fielder addressed the email to Moore, Milne and Gray's campaign. The clerk said she informed Moore last week that data was missing from the electronic records. But she said Moore declined an invitation to come and sift through her office's paper records for a fuller picture and instead blasted out the attacks, which Fielder described as "misleading at best, bordering on blatant lies." The clerk said she was speaking up because her "conscience" could not allow her to stand idly by as inaccuracies "shape[d] the story."

"I am not taking a political side in sending you this email," Fielder wrote. "I am taking a moral stand."

Reached Monday, Moore said the town clerk had given her no indication that paper records existed after the 2008 election. And even though it now appeared that her allegations were at least partially inaccurate, Moore stood by calling Milne an inconsistent voter and said she had no plans to rescind her press release. In fact, she asserted, the attempts to clear Milne's name show that his campaign is "clearly upset that his inconsistent record was exposed," which is why it is now "working to discredit [our] group."

"Both campaigns have referenced inconsistencies in their voting histories," Moore said. "I think that it's time to move on now."

Milne disagreed. He called on Gray to "come clean" about her voting record and "disassociate herself" from the super PAC, which he described as a "shady and dishonest organization."

"Not only is Molly Gray lying about her own voting record, but now she has her supporters lying about mine," he said in a press release.

On Monday, Gray's campaign manager, Sheehan, declined to comment on the scuffle between Milne and the super PAC. She did the same when asked Milne's record on Friday, before the town clerk's clarification, though she added, "We'll let others do the talking."

'Watching what they say'

Sumner, the undecided Burlington voter, attended Gray's community forum with a question on her mind. "If she's going to be so directed on climate, then I'm probably not going to vote for her," she said before Gray spoke.

Sumner got her answer 30 minutes later. Asked by moderator Daniel Barlow about how she would tackle the climate crisis were she elected, Gray quipped, "How much time do we have?"

She then referenced her stop at SunCommon earlier in the day and said she viewed the climate crisis as one of the "greatest job opportunities of our time," one that needs to be met with the same urgency that the state has afforded the pandemic.

"I think it means we invest in solar; we invest in weatherization; we invest in workforce development that grants jobs from our schools into the businesses that are going to help us figure out climate change," she said. "The time to act is now."

Sumner stood up and asked the candidate about her other concern: mental health. "We're not addressing what's really going on here," she said. "Counselors can't go out and visit clients due to the pandemic. Most people don't have a phone or a computer to talk to the counselor. And I'm just wondering, what are your thoughts?"

Gray spoke for a few minutes about how she understood Vermont's mental health crisis was a major issue, about how she hoped to use the lieutenant governor's office to "demystify" mental health, to "make it part of the conversation."

After the event, Gray approached Sumner and asked her to share what she viewed as the greatest need. The two spoke for a few minutes, then Gray made her way through the crowd.

Reviewing Gray's performance, Sumner said she tensed up as the candidate launched into her answer about the climate. But she conceded that Gray had a point: Renewable energy would lead to jobs, "which is what we need."

"It doesn't seem like it's 100 percent her priority," Sumner said. "So that helped me out."

And while Gray didn't offer many concrete answers on mental health, Sumner did feel her "compassion" on the issue. Now that they had met, "I might reach out and say, 'Hey, listen, I spoke to you at the park, and I'm kind of curious: Have you given it any more thought?'"

Asked whether Gray had managed to win her vote, Sumner said she hadn't. But she hadn't lost it, either.

"I'll just keeping watching what they say," she said, a promise she seemed likely to keep.

Disclosure: Tim Ashe is the domestic partner of Seven Days publisher and coeditor Paula Routly. Find our conflict-of-interest policy at sevendaysvt.com/disclosure.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.