- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

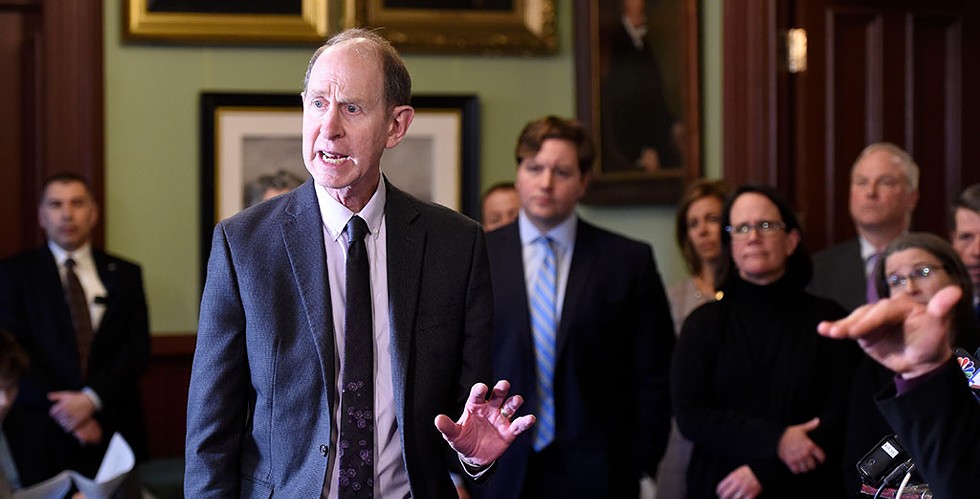

- Gov. Phil Scott

In the lobby of the governor's office, a large whiteboard mounted on an easel warns visitors to "STOP" and wash their hands before entering and leaving. There is, however, nobody left to warn.

Five weeks after the global coronavirus pandemic arrived in Vermont, the fifth floor of Montpelier's Pavilion Office Building is on lockdown. Visitors are prohibited and employees scarce, allowed to come to work only when absolutely necessary. The lights in the reception area are switched off, and the offices of senior staff are empty.

These days, only Gov. Phil Scott remains, running state government via videoconference from his corner office overlooking the Statehouse. "I know that everyone is just a phone call or a Skype call away," he said. "But it's been noticeable when I walk down the hall and I'm the only one here — and that happens a lot."

From his lonely perch, the 61-year-old governor is overseeing the response to the greatest crisis Vermont has faced since the Great Depression.

Already, the novel coronavirus known as COVID-19 has claimed the lives of 29 Vermonters and infected a total of 752 others. It has ripped through nursing homes — killing 10 at Burlington Health & Rehabilitation Center — and scaled the walls of Northwest State Correctional Facility, where at least 50 prisoners and officers have contracted the disease.

To slow its spread through the rest of the state, Scott has ordered strict mitigation measures that would have been unimaginable months ago: dismissing schools, closing businesses and confining most Vermonters to their homes. These decisions may have saved lives, but they have crippled the economy, decimated the state's finances and left more than 73,000 unemployed.

"Had you asked me any time before this whether I'd be shutting down businesses in Vermont, it would've been a resounding no. Never. Not on my watch," said Scott, a second-term Republican and former business owner. "But here I am."

In the absence of leadership at the federal level, governors around the country have stepped up to fill the void. They've had to devise their own testing programs, source their own face masks and compete with one another for a limited supply of ventilators.

As governor of the second smallest state in the union, Scott has found himself fighting a global pandemic with the resources of a midsize metro area. He's had to supplement his staff of 17 with a hastily recruited group of former government officials who volunteer from their home offices. And he's had to count on local business owners to fabricate face shields and navigate Chinese supply chains.

Seven Days interviewed 30 people who have worked with or for the Scott administration as it has navigated the coronavirus crisis. Those who have spent the most time with the governor described his approach as data-driven, decisive, calm and empathetic. "I would go to war with this guy," said Secretary of Human Services Mike Smith, a former Navy SEAL.

Even Scott's adversaries praised him for putting public health before politics. "He's listening to the experts," said Vermont Democratic Party chair Terje Anderson. "He's working collaboratively with the legislature, by all accounts, and that's very different from what we're seeing in Washington."

The pressure is undoubtedly taking a toll on the governor. "It's a lot on his shoulders," said House Speaker Mitzi Johnson (D-South Hero). "It's a lot of stress. It's a lot of hours."

Like many frontline workers whose weekends have become indistinguishable from their weekdays and whose nights resemble their days, Scott says he feels like he's stuck in a time warp. "I'm living in dog years, because a day seems like a week, a week seems like a month, a month seems like seven months," he said.

After returning home late one night last week and showering, Scott recalled, "I started putting on my clothes for the next day. And I caught myself when I put on my dress shirt, and I thought, Oh, wait a second. No, this is night. I'm just getting home ... The routine is just constant, so you lose track of where you are."

It's too soon to know how Vermont will fare in an outbreak that has devastated some states and countries while just glancing off others. It's too soon to know whether Scott has overreacted, underreacted or struck just the right balance.

But at a press conference last Friday in the basement of the Pavilion, the governor and his advisers expressed cautious optimism that the state's worst-case projections might not come to pass. In the weeks since Scott ordered Vermonters to stay home, the disease's growth rate had begun to slow, said Commissioner Mike Pieciak of the Department of Financial Regulation. The administration now believes the state might have the medical capacity to treat every patient as the pandemic peaks in late April or early May, though hundreds may still be hospitalized and thousands infected.

"This news is positive. However, our future is not guaranteed," Pieciak said, a protective face mask hanging around his neck. "The trends can turn on a dime if we stop and relent from social, personal and professional sacrifices that everyone is making in their daily lives."

Scott, who had arrived at the press conference wearing his own camouflage mask, emphasized that his administration was "not declaring victory at this point in time." And he pointed out a cruel irony: "The more successful we are with this social distancing and all the measures we've taken, the more it's going to look like we overreacted," he said. "And I'll take the blame, the burden of that, over the alternative path where we have more deaths than we predicted."

'When It Became Real'

- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

- Human Services Secretary Mike Smith

On the first day of March, Scott received an alarming phone call from New Hampshire Gov. Chris Sununu. "It was basically, 'We have a problem,'" Scott recalled Sununu saying.

A Dartmouth-Hitchcock medical center employee had contracted the coronavirus while traveling in Italy, Sununu informed him, and had broken quarantine to attend a party at a White River Junction nightclub on February 28.

It wasn't news to Scott that COVID-19 posed a threat to Vermont. His health commissioner, Dr. Mark Levine, had first warned him about it in a weekly report at the end of January and had briefed his cabinet days later. The Department of Health had activated its Health Operations Center in early February and was monitoring Vermonters who had recently returned from China, where the virus originated. On the day of the White River Junction party, Levine and other state officials had announced the formation of a coronavirus task force at a press conference in Waterbury.

"Now is the time for all of us to prepare mentally and logistically for possible disruptions to our daily lives," Levine had said.

But according to Scott, it was Sununu's call that woke him up to the crisis to come. "That's when it became real to me," he said. "Suddenly it struck me how vulnerable we really were by the actions of one person."

A week later, on Saturday, March 7, Smith, the human services secretary, was getting ready to go to bed when his phone rang. "I picked it up, and Mark Levine says, 'You know why I'm calling,'" he recalled. "I said, 'Yeah, I do.'"

Health department officials had determined that a patient at Bennington's Southwestern Vermont Medical Center had been diagnosed with the disease. It was the first known case in Vermont.

Scott, who was attending a Norwich University hockey game, learned of the situation from his chief of staff, Jason Gibbs. The governor left the arena to take a call with Smith, Levine and Gibbs. "I don't even think I got through the first period," Scott said.

The news came as lawmakers and administration officials were returning from the legislature's annual Town Meeting Day recess. Public Safety Commissioner Mike Schirling had been vacationing in Florida but hopped on a plane home a day early to help activate the State Emergency Operations Center in Waterbury. "Clearly the workload was going to change," he said.

Vermont Emergency Management, a division of Schirling's department, had been "dusting off" its pandemic plans to prepare for the arrival of coronavirus, he said. But it soon became clear that they wouldn't suffice.

Ordinarily, according to Vermont Emergency Management director Erica Bornemann, disasters come and go in a relatively short period. And, typically, neighboring states or the federal government can lend a hand. Neither has been the case this time.

"The major challenge is really rooted in the scale and duration of the event," Bornemann said. "We had plans, but even at the national level the best plans could not have contemplated the challenges this event has given them."

'Flare in the Air'

- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

- Health Commissioner Mark Levine

Vermont has never seen a two-week period of government intervention quite like the one that began on Friday, March 13. That day, legislators voted to shutter the Statehouse and, at a late-afternoon press conference, Scott declared a state of emergency.

"While many will either not get [the coronavirus] or see mild symptoms, we all have to do our part to slow it down to protect the ill and older Vermonters who are at risk," Scott told reporters at Montpelier's Vermont History Museum. "This is the lesson from other countries like China and Italy, where efforts to slow the spread were not implemented early enough and now we see them struggling."

The initial declaration prohibited gatherings of 250 or more people, restricted access to long-term care facilities and expanded unemployment insurance to cover those affected by the disease. It would serve as the legal basis for a series of subsequent orders that would, in the coming days, close down much of the state.

"That was the first flare in the air that folks needed to buckle down and hold on," said Tayt Brooks, a senior administration staffer. "Your life is going to change."

Over the course of the next week, Scott issued decrees one by one, closing the state's schools, then its restaurants and bars, then its childcare centers. He suspended nonessential surgeries, further restricted gatherings to just 10 people and shut down "close-contact" businesses, such as gyms and barbershops.

Day after day, Scott appeared at press conferences alongside Levine — a tall, gangly physician — to answer questions about each new order and to explain that it had been driven by "the data and the science."

According to Levine, Scott has yet to overrule one of his recommendations, though every significant decision requires sign-off by the governor's office. "I'd say there wasn't a lot that we had to really push down anyone's throat," the commissioner said, calling the state's approach "pretty darn aggressive."

The Republican governor's progressive approach to public health may have something to do with the views of his spouse, Diana McTeague Scott, a nurse at a central Vermont doctor's office. "I certainly hear about some of the challenges people are facing and the struggles they have," he said. "So I would say it would have to influence me in some ways." (Given that she could be exposed to COVID-19 at work, the couple is taking precautions to avoid infecting one another, the governor said; if either experiences symptoms, Scott plans to sleep in his state office.)

As Scott rolled out the mitigation measures, he often telegraphed his next move. Advisers say the goal was to avoid surprising Vermonters about what was to come and to give them time to emotionally — and sometimes logistically — prepare. When the governor ordered businesses and nonprofits to implement work-from-home plans on March 23, for example, he made clear that more draconian measures would follow. Sure enough, the next day he issued his most sweeping directive yet: a "Stay Home, Stay Safe" order that closed all but the most critical businesses.

Senate President Pro Tempore Tim Ashe (D/P-Chittenden), a frequent adversary, hailed the governor's communications strategy.

"I think he's just taken a very measured and calming approach to ease people into each new level of restriction or executive order to ensure that people actually comply with them," Ashe said. "At the end of this, it'll be that approach of getting buy-in at each step of the way that will likely be what makes our efforts pay dividends."

Early in the crisis, some Scott critics questioned whether he was moving too slowly. Two days after he declared a state of emergency, Democratic gubernatorial candidate Rebecca Holcombe called on him to close the state's schools and criticized him for failing to lay the groundwork for such an action.

"Gov. Scott's response to the coronavirus is inadequate," she wrote on Twitter on March 15. "The administration must move faster & more aggressively."

Holcombe, who had previously served as Scott's education secretary, was hardly the only one seeking the dismissal of K-12 schools. Parents, superintendents and the state teachers' union, the Vermont-National Education Association, were all making a similar case.

"People were looking for direction," said Holcombe's successor, Education Secretary Dan French. In his view, the question wasn't whether to close the schools but when. Doing so before there was evidence of community spread could prove ineffective, and it would further disrupt the lives of medical professionals with children in the system.

On the same day Holcombe made her demand — though not as a result of it, administration officials say — Scott ordered schools closed within the next three days. "I think there was a tremendous amount of relief when the decision was made," French said.

Others have criticized the administration for acting too swiftly and failing to consult those affected by a decision. Not long after the Department for Children and Families closed the Woodside Juvenile Rehabilitation Center last month to make room for psychiatric patients diagnosed with COVID-19, two young people escaped from a makeshift replacement facility in St. Albans.

Steve Howard, executive director of the Vermont State Employees' Association, said the incident could have been avoided had Woodside staffers been given the opportunity to weigh in on the suitability and security of the facility. "That was just stupid," he said. "They needed to slow that down."

The rollout of a plan to require each school district to care for the children of essential workers was equally rushed and required multiple amendments after the fact.

Johnson, the House speaker, said that while the process appeared chaotic at times, such an outcome was likely unavoidable, given the circumstances. "Honestly, with every single [order] I heard some people saying we really needed to do this yesterday or last week, and I've heard other people say, 'What the heck? We're not there yet!'" she said. "So you're never gonna hit 100 percent on that. But in the grand scheme of things, I think we did hit the relative sweet spot."

'Here We Go'

- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

- Gov. Phil Scott addressing reporters last Friday in Montpelier

Former health commissioner Harry Chen was quarantined at home in late March after returning to Vermont from a trip to Uganda to teach emergency medicine. He was restless and wanted to lend a hand. Word of his interest soon reached Smith, the secretary of human services.

"Mike Smith called and basically said, 'We need you,'" recalled Chen, an emergency room doctor who also once held the secretary's job on an interim basis. "Luckily, I didn't think about it too much and said, 'Sure.'"

With Levine focused on day-to-day management of the Department of Health, Smith was looking for help planning for a medical surge in the event that the pandemic overwhelmed existing hospital resources. A key component of his work, Chen said, was "beating the bushes for health care providers who aren't already engaged."

Smith and Scott, meanwhile, were beating the bushes for other veterans of state government to return to service in a moment of need. Even in the best of times, Vermont's governors are chronically understaffed — relying on just 17 employees on the fifth floor of the Pavilion to coordinate an 8,300-person workforce spread across nearly 30 agencies and departments.

When the governor needed help fixing the messy closure of the state's childcare system, he turned to an unlikely, bipartisan pair: Neale Lunderville, who had served as Republican governor Jim Douglas' administration secretary, and Liz Miller, who was Democratic governor Peter Shumlin's chief of staff.

"The call comes, you gotta answer it," Miller said.

"I think I texted Liz something to the effect of, 'Here we go!'" said Lunderville, who had previously been pressed into service to run Shumlin's Tropical Storm Irene recovery efforts.

Lunderville's partner, Dennise Casey — who ran two of Douglas' campaigns and served as deputy chief of staff — also joined the team, as did Clarence Davis, who had recently served as interim deputy secretary of human services.

Smith, especially, needed the help. The Agency of Human Services is a massive bureaucracy that accounts for half the state's spending. It includes the Department of Health and five other departments serving Vermont's most vulnerable populations — inmates, children, the elderly, the poor and those with mental illness.

Near the start of the crisis, Smith recruited Kerry Sleeper, a former public safety commissioner, to serve as his interim deputy secretary. The Vermont native had been commuting to Washington, D.C., for more than a decade and had recently retired from the Federal Bureau of Investigation. "He built the emergency operations center and the operations plans — and we need that integration between AHS and the emergency operations center," Smith explained.

Sleeper said he "couldn't imagine doing anything else at a time like this, quite honestly," but he doesn't intend to stay. "I have assured Mike I'm not interested in a long-term state government role," Sleeper said.

Before the outbreak, the Scott administration was already stocked with veterans of the Douglas administration, including Gibbs, Smith, Brooks, Secretary of Administration Susanne Young, Secretary of Civil and Military Affairs Brittney Wilson, and director of workforce expansion Dustin Degree. With Lunderville, Casey and Sleeper back in the fold, it might as well have been a cast reunion.

"When you're in a crisis situation, knowing the people that you're working with and leading with, understanding how they work, having been through previous crises in the past is invaluable," Sleeper said. "It's absolutely invaluable."

'Every Element of the Machine'

- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

- Commerce Secretary Lindsay Kurrle

At every level of state government, workers have stepped up and, in many cases, taken on new roles to combat the pandemic.

Department of Motor Vehicles employees have fielded phone queries for the Department of Labor. State troopers have joined Department of Health staffers in tracing the contacts of COVID-19 patients. Parole officers have relieved corrections officers in the state's understaffed prisons. State property managers have leased hotels and motels to quarantine the infected. Procurement specialists have helped businesses retool to produce medical supplies.

"Every element of the machine has turned towards COVID-19," said Deputy Commerce Secretary Ted Brady.

When Scott needed somebody to model the spread of the coronavirus to determine whether the state had enough equipment and hospital beds, he turned to Pieciak, whose Department of Financial Regulation typically oversees the insurance and banking industries.

"I wasn't anticipating the thought that we might be tasked with looking at the rate of disease growth, but that's what the governor asked that we coordinate," said Pieciak, who enlisted the help of academics and consultants. "We certainly said we'd be happy to help."

All the while, many of these state workers have continued to do their day jobs. "Medicaid still needs to run. DCF still needs to manage foster care," Lunderville said. "It's an extraordinary burden for folks, and they work around the clock."

In recent weeks, they've done so largely from home. Excluding those who work at the state's 24-hour facilities, such as prisons and mental health institutions, roughly three-quarters of the workforce has gone remote, Young estimated.

Even the State Emergency Operations Center, which typically operates out of a war room in Waterbury, went fully virtual for the first time last week. According to Bornemann, the emergency management director, doing so was essential to keep her staff safe and ensure continuity of operations — but it also posed new challenges.

"It means we have to be a lot more deliberate about deliberating," she said. "It means we're on the phone most of the day."

In the early weeks of the outbreak, a skeleton crew of seven senior Scott staffers remained on the fifth floor of the Pavilion. They were required to keep their distance from the governor and closely monitor themselves for symptoms. Last week, in order to protect Scott, Gibbs ordered everyone else home. Only those specifically invited — to staff a press conference, say — are allowed to return.

Secretary of Commerce Lindsay Kurrle finds herself running a state agency under the same roof as her three children, ages 13, 17 and 19. That doesn't mean she has time to ensure that they're adapting to remote learning. "I am here and I see their faces, but there are times when I get to the evening and I realize I haven't really been able to check in," she said.

According to Kurrle, Scott frequently touches base with her and fellow cabinet members to make sure they're coping with the personal strains of the crisis.

Those who can't work from home typically have the hardest, most dangerous and most essential jobs. Chris Cole, commissioner of the Department of Buildings and General Services, calls the custodians and maintenance workers who deep-clean the state's facilities and keep them running "heroes" of the COVID-19 response.

And then there are the corrections officers, at least 18 of whom have already contracted the coronavirus in the state's prisons. The state workers' union recently negotiated a $1.50-per-hour premium for those who work in 24-hour facilities or have direct contact with the public. Those who work with or near COVID-19 patients get a larger pay bump of 20 percent. But Howard, the VSEA chief, says that's not enough to compensate for the hardship and risk.

"There's just real fear. You can hear it in people's voices," he said. "'I don't want to get sick. I don't won't to die. I don't want to get my family sick.'"

'On Its Own'

- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

- Gov. Phil Scott

Scott has never been fond of President Donald Trump, but he's been careful to avoid criticizing his fellow Republican's response to the pandemic — perhaps because the president has taken to using the nation's emergency supplies to reward his allies and punish his enemies.

"I'm sure in the aftermath there will be enough time for criticism, so I'll just stick to the positive points," the governor said, singling out for praise Dr. Anthony Fauci, the omnipresent director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and Dr. Deborah Birx, Trump's coronavirus response coordinator.

Scott also called Vice President Mike Pence, Trump's coronavirus point man, "extremely helpful" to Vermont.

By mid-March, according to Scott, the state was running low on testing supplies and was in danger of running out within days. "So I called Gov. Sununu and I asked him if he happened to have any supplies that we could borrow, because it didn't appear that the federal government was coming through as quick as we needed," Scott recalled. Sununu didn't have any to spare but organized a three-way call with Pence. "We had a good conversation that Saturday afternoon, and he pledged to get us more, which he did, and bailed us out," Scott said.

Others are more direct about the failures of the feds.

"We clearly, as a nation, were unprepared — and that's a fundamental responsibility of the federal government to ensure we are prepared for contingencies," said Sleeper, the former FBI official and deputy human services secretary. "The state was and is literally on its own in the planning and response realm."

According to Bornemann, Vermont was "operating under the assumption" that it could draw down a vast quantity of gear and equipment from the Strategic National Stockpile. But, she said, "We've gotten all we're going to get."

Levine points to two actions the Trump administration could have taken to contain the outbreak: increase testing capacity and broaden the travel ban from China to Italy and the rest of western Europe earlier than it did. But, the health commissioner said, "We deal with the hand we're dealt."

Scott's leadership style couldn't be more different from Trump's. Those who work with the governor say he immerses himself in the details of the state's response but doesn't pretend to know all the answers. According to Bornemann, he's the first governor she's encountered who tunes in every day to the State Emergency Operations Center's updates.

"He's got his video on. We can all see him in his office," she said. "Those are important measures to show folks that are on the ground that he cares — that he is very engaged."

The contrast with Trump is particularly clear at Scott's thrice-weekly press conferences, during which he typically delivers a brief pep talk and then recedes to the back of the stage.

"In his responses, he's got the experts with him and he's deferring to them, rather than answering questions on his own and making stuff up off the top of his head," observed Johnson, the House speaker. "And unlike the president, this governor is willing to make difficult choices with the specific goal of protecting the health and safety of Vermonters."

'The Vermont Method'

- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

- Public Safety Commissioner Mike Schirling

Earlier this month, U.S. Rep. Peter Welch (D-Vt.) learned from a congressional colleague that a Connecticut lumber baron was about to order hundreds of thousands of face masks from China to distribute to local health care workers. The man, who regularly did business in China, also had ties to Vermont and wanted to know whether the state was interested in joining the order.

Welch quickly informed Lunderville and Miller. "Welch reaches out to us and says, 'I got this guy, and you need to call him tonight — like, the order's going in,'" Lunderville said.

Scott was on the phone with the Connecticut man in no time. "I said, 'You don't know me. I'm Gov. Phil Scott, and this is probably the last thing I ever imagined I would ever be doing — cold-calling someone on a Friday night, asking if they had any N95 masks available,'" Scott recalled. "He said, 'I'd be more than willing to help Vermont, my second home.'"

Welch was impressed. "It was a turnaround time of two hours, if that. And that's good work," he said. Now 100,000 surgical masks and 500,000 KN95 masks are on their way to Vermont.

"It's not a typical role," Schirling, the public safety commissioner, said of the gubernatorial procurement. "The governor is both the lead on all of these things and he steps in to play utility player, as necessary."

When the state realized it needed more ventilators, Scott called Adam Alpert, whose family had recently sold BioTek, the Winooski-based life sciences manufacturer. "I didn't know why I was calling him, but I thought, Here's a guy who's well-connected throughout the world, and maybe he could help us," Scott said.

Sure enough, Alpert knew the owner of a major ventilator manufacturer and got in touch. According to Schirling, the state has since placed an order, though it's not clear when the ventilators will arrive. "Unfortunately, it's not like Amazon Prime," he said.

"It really does feel to me like he is engaged, understands the subtlety of the problem," Alpert said. "I came away kind of inspired ... In the crisis that befalls us, he was displaying the kind of qualities I'd hope to see from leadership."

Throughout Vermont, businesses and nonprofits have been working to provide the medical supplies the state desperately needs. Revision Military in Essex has donated face shields, Portabrace in Bennington is producing masks, and Burton in Burlington is donating goggles and masks and manufacturing face shields instead of snowboards.

"We're using the Vermont method, which is: Who do you know?" said Cole, the buildings and general services commissioner, who has coordinated the procurement process with Schirling and Charlie Miceli, a supply chain specialist at the University of Vermont Medical Center.

Last month, the trio caught wind that Concept2 — the Morrisville-based rowing machine manufacturer — was working to obtain a large quantity of masks from China to distribute to health care providers in the area. The company's Shanghai-based parts supplier had relationships with factories that made the masks and was preparing to ship 500,000 to Vermont, according to Trevor Braun, a Concept2 product designer.

Within days, the state had piggybacked on the order and purchased another 2 million.

"It was really sort of heartening to see how trusting they were of Concept2 and our supplier to bring in critical supplies in a critical time," Braun said. Those masks reached a Shanghai airport late last week and could arrive in Vermont soon.

Al Gobeille, a senior executive at UVM Medical Center and former human services secretary, said the ad hoc procurement process had benefited from the personal familiarity of those involved. He said he'd known Schirling well since Gobeille was running Burlington's Breakwater Café & Grill and Schirling was the city's police chief.

"So when I called him and said we need to talk about [personal protective equipment], it wasn't like, 'Do I trust you?'" Gobeille said. "There was never a minute of that."

Sometimes Scott plays an even bigger role in the process. Earlier this month, he saw television news reports showing Vermont National Guard members building a medical surge facility in Essex. He was impressed but also alarmed.

"None of them were wearing masks. They weren't socially distancing," the governor said. "So I called Tracy [Delude], my scheduler, who does quilting, and I said, 'Tracy, I need some masks. I need some built. And I'd like some cool kinda masks.'"

Delude tracked down a bolt of camouflage fabric, and Scott got in touch with Vermont Glove owner Sam Hooper through his brother, Rep. Jay Hooper (I-Brookfield). "I said, 'If I can get you this material, can you make me these masks?'" the governor recalled.

Two days later, Scott delivered the final product to the Essex surge facility — and kept one camo mask for himself.

'Everyone Knew That We Were Vulnerable'

- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

- Gov. Phil Scott

Five weeks into the crisis of his career, Scott appears to be getting good marks from most quarters. Even Holcombe, the Democratic rival who initially called his approach "inadequate," now credits him for "trying to keep us at home, keep us socially distanced and expand the use of testing."

"I appreciate what the governor has done to respond to the public health crisis," she said.

According to Lt. Gov. David Zuckerman, who is also seeking the Democratic gubernatorial nomination, Scott "has responded reasonably quickly and relatively effectively."

But the governor is hardly out of the political woods. His decision to shut down large portions of Vermont's economy has frustrated and confused many business owners, who have closed up shop and laid off tens of thousands of employees.

Since Scott issued his "Stay Home, Stay Safe" order last month, the Agency of Commerce and Community Development has received more than 3,700 requests for additional guidance, according to Deputy Secretary Brady. Some have expressed confusion over whether their business must close, while others have complained about competitors flouting the rules.

"I think I'm not going out on a limb to say there were entities and companies who were not happy to stop work," said Brooks, the senior Scott staffer. "Most companies do not want to shut down."

Certain sectors, such as the construction industry, have been particularly vocal — arguing that they can perform their work without spreading the disease.

"It came as a shock. We're the only state that has construction shut down to the extent that it's shut down," said Dick Wobby, executive vice president of the Associated General Contractors of Vermont and a longtime friend of the governor. "Geez, New Hampshire's got construction rolling. Maine's got it. People are dying left and right in New York, and they've still got construction going." Wobby added that "the naysayers" in his industry have since come around and now understand the need to stay home.

Kurrle, the commerce secretary, said she suspected the decision had weighed heavily on Scott, a former owner of DuBois Construction, the Middlesex excavation company. "If I had to guess, that's been a really tough one, but he has stood with his conviction that, right now, we need to keep Vermonters healthy and keep them alive," Kurrle said.

In the rush to deploy the "Stay Home, Stay Safe" order, the administration created unanticipated problems for some industries. The directive required the tourism sector to cease taking reservations for all future visits — including hotel stays for weddings scheduled for 2021.

"That is quite puzzling and is something that we are working to get changed," Vermont Chamber of Commerce president Betsy Bishop said last week. "They're operating in a very fast-paced way, and all the nuances of the future and road map to recovery probably aren't top of mind."

Days later, Scott remedied the problem in a new order, allowing reservations after June 15, as long as the state of emergency is over.

Scott's executive orders have also led to mass layoffs. Since mid-March, more than 73,000 Vermonters have filed initial claims for unemployment insurance, catapulting the state's unemployment rate to 23 percent.

"The enormity is just really, really incredible," said Degree, the director of workforce expansion. "It's truly massive.

The deluge of claims is being processed by the Department of Labor's 1970s-era IBM COBOL mainframe, which frequently crashes under the burden. Degree refers to it as "legacy software from the silent-film era." Complicating matters, Congress recently extended unemployment insurance to sole proprietors and the self-employed — but left the implementation of the program to the states.

Ashe, the Senate president, says he fears the resulting "double tsunami" will overwhelm the department and further delay payments. "We've made very clear to the governor that that's the thing our constituents are suffering from the most right now," he said.

At Scott's press conference last Friday, Interim Labor Commissioner Michael Harrington acknowledged the hardship the problem has caused. "We can do better, and we will do better," he pledged.

Though Scott is hopeful his executive orders have spared the lives of many Vermonters, they did not prevent the fatal outbreak at Burlington Health & Rehab, nor a more recent one at Burlington's Birchwood Terrace nursing home, which has claimed three residents. And if more inmates and officers at Northwest State Correctional Facility — or the state's five other prisons — become infected with COVID-19, the outcome could get even deadlier.

"I don't know what we could have done differently, but certainly those are areas that weigh heavily on me, because I knew that we were vulnerable there," Scott said of Vermont's nursing homes and correctional facilities. "Everyone knew that we were vulnerable, and we weren't able to keep that from happening."

For weeks, the American Civil Liberties Union of Vermont and other criminal justice reform groups have urged the administration to provide medical furlough to prisoners who are old or unwell, arguing that doing so could save their lives. Though the Department of Corrections has recently reduced its in-state prison population from 1,649 to 1,413, it has resisted implementing a broad-based furlough initiative.

At the governor's press conference last Friday, Smith struck an unusually caustic tone, insisting that he would not release "hard-core criminals" and listing the violent offenses committed by many older prisoners.

Scott and Levine both blame the federal government for providing insufficient testing resources early in the outbreak. "I have no regrets about anything beforehand, because it was all out of our state's control," the health commissioner said. "But now that it's in our control, I feel very positive about the fact that the first thing I said was, 'We're gonna do more testing.'"

At the same time, Levine continues to insist that, even if every Burlington Health & Rehab patient had been tested as soon as the first was diagnosed on March 16, his department would not have responded differently. "All of the things that our [epidemiological] teams do when they go into a facility like that are done whether you're testing or not," he said.

Similarly, even though at least 32 prisoners at Northwest State were infected before any showed symptoms, the Department of Health does not plan to test inmates at the other state prisons until "we have a reason to do so," Smith said.

'A Different Normal'

Every decision Scott has made since the coronavirus reached Vermont, he said, has felt like "the biggest, most difficult decision" yet. But, he added, "I think that the decisions of the future may be even more difficult."

Unlike Trump, who promised weeks ago that church pews would be filled by Easter Sunday, Scott has studiously avoided setting expectations for when he might lift his executive orders. Naming an arbitrary date, he has said, would be irresponsible. Even when he recently extended all of his existing orders through May 15, he made clear that his timelines could still shift forward or backward.

At a press conference on Monday, Scott acknowledged that the extension "was a disappointment for many," but he and Levine suggested there was reason for optimism.

"The number of new cases per day is getting smaller, and it's leveling off," Levine said. "We seem to be approaching, if you will, a plateau. We'll see if that is a sustained phenomenon or just a trend over several days."

And while the commissioner acknowledged that the risk of infection was still great for vulnerable Vermonters in prisons, nursing homes and other such facilities, he emphasized that the state had avoided "major outbreaks or spikes" in the general population.

The administration is already planning for the next stages of its response. Last weekend, Levine named a group of experts to study the serological testing that may help determine who has developed immunity to COVID-19 and can therefore safely return to work. On Tuesday, Scott appointed a task force to consider how to reopen and rebuild Vermont's economy. He also spoke by phone with Sununu and Maine Gov. Janet Mills about the states' respective approaches and how they could coordinate.

Scott said at Monday's press conference that he would take a "phased approach" to dismantling the new regime he has created. "We will continue to watch the trend and our hospital capacity so that as soon as we can begin to dial back some of these steps in a measured, responsible, safe manner, we will," he said.

Someday, the governor promised, "We'll slowly be able to get back to normal." But, he warned, "It may be a different normal than we had before."

Timeline

- January 21: First COVID-19 case confirmed in the U.S.

- January 24: Dr. Mark Levine first mentions COVID-19 in weekly report to Gov. Phil Scott

- February 3: Vermont Department of Health activates Health Operations Center to monitor coronavirus

- February 4: Dr. Levine first briefs Gov. Scott's cabinet on the coronavirus threat

- March 1: N.H. Gov. Chris Sununu alerts Gov. Scott to COVID-19 patient in White River Junction

- March 2: Gov. Scott forms coronavirus task force

- March 7: First COVID-19 case confirmed in Vermont

- March 10: Vermont activates State Emergency Operations Center

- March 13: Gov. Scott declares state of emergency; Statehouse closed

- March 15: PreK-12 schools ordered to close

- March 16: First COVID-19 case detected at Burlington Health & Rehabilitation Center

- March 17: Childcare centers ordered to close

- March 19: First two COVID-19 deaths in Vermont

- March 20: Nonessential surgeries ordered to be canceled

- March 21: Gatherings restricted to 10 or fewer people; close-contact businesses closed

- March 23: Businesses and nonprofits urged to implement work-from-home procedures

- March 24: Vermonters ordered to "Stay Home, Stay Safe"

- March 26: Schools ordered closed for remainder of academic year; Vermont unemployment claims soar to 15,000

- March 27: President Donald Trump signs third coronavirus relief package into law, providing an estimated $2 billion to Vermont

- March 30: Travelers ordered to quarantine for 14 days upon arriving in Vermont; first COVID-19 case detected at Birchwood Terrace

- April 1: First COVID-19 case detected in an officer at Northwest State Correctional Facility

- April 2: State modeling projects peak coronavirus caseload approaching

- April 5: Vermont infection rate surpasses 500 cases, 22 deaths

- April 9: Universal testing at Northwest State Correctional Facility detects major COVID-19 outbreak

- April 10: All emergency orders extended through May 15

Disclosures: Paul Heintz's spouse, Shayla Livingston, works for the Vermont Department of Health. Tim Ashe is the domestic partner of Seven Days publisher and coeditor Paula Routly. Find our conflict-of-interest policy at sevendaysvt.com/disclosure.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.