- James Buck

- Amanda Bean

Amanda Bean's longtime opioid addiction took a turn last summer. The drugs she bought on the street were noticeably stronger but wore off faster — so she shot up more often each day. She also started to use methamphetamine, which had become cheaper and more readily available than the cocaine she preferred. She would sometimes go days without sleep, she said during a recent interview from jail, drifting further and further away from reality.

Then the overdoses began. Dozens throughout the fall and winter, until it felt as if each time she used, she was awakened by someone standing over her with Narcan, the OD-reversal medicine. In April, on Easter weekend, she overdosed at her mother's apartment. Each day the following week, she landed in the ER for overdoses, prompting a concerned doctor to finally ask her what the hell was going on. "I don't know," she recalled telling him.

By last month, Bean had racked up more than 40 pending criminal charges, most for stealing to support her addiction. On May 4, she appeared for a hearing at the Burlington courthouse. Chittenden County State's Attorney Sarah George, who had gotten to know Bean over the years through the legal system, sat in on the hearing. George had noticed the woman's descent seemed to be gaining speed, and yet, she later recalled, she couldn't believe how much worse Bean looked that day.

Scabs covered Bean's gaunt face, and her clothes hung loosely from her frame. She was clearly under the influence: Her arms and legs moved uncontrollably, and her head lolled back and forth, as if she would nod off at any moment. The judge, noting Bean's condition, ultimately postponed the hearing.

George said she later wondered to herself: How is she still alive?

It has been nearly a decade since then-governor Peter Shumlin dedicated his entire State of the State address to what he described then as Vermont's "full-blown heroin crisis." That led to the build-out of what has become a renowned "hub-and-spoke" drug treatment system; just a few years ago, it appeared the state was making tangible progress.

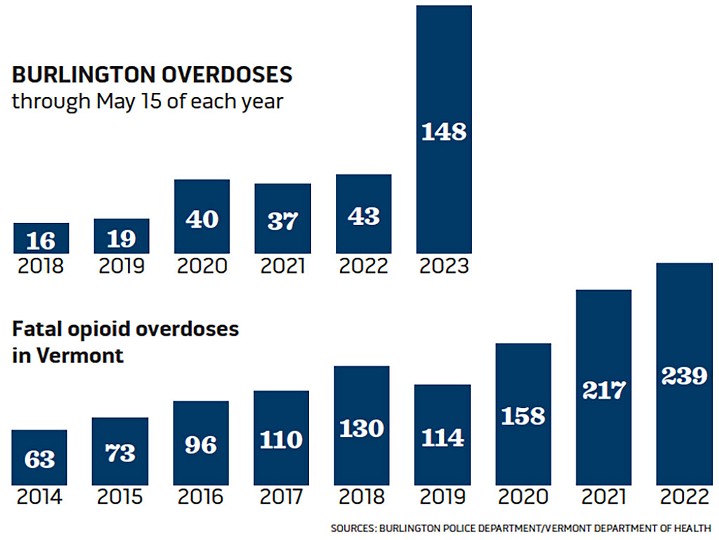

But today, the scourge of drugs is worse. More people died from fatal opioid overdoses between 2020 and 2022 — 614 — than in the previous six years combined. And some people like Bean who have long struggled with addiction seem sicker than ever. Many frontline workers now have a mental list of people they expect to die in the coming year.

The deepening crisis, exacerbated by the pandemic, is the result of a deadlier drug supply. Fentanyl, a powerful synthetic narcotic, has replaced heroin as the main opioid available on the streets, driving up overdoses and complicating treatment efforts. Methamphetamine has arrived, ensnaring people in a tough-to-treat addiction that can ravage both body and mind. Xylazine, an animal tranquilizer, is increasingly present in street drugs; its side effects include wounds that can lead to amputations.

"Being addicted to an intravenous drug has become a game of Russian roulette, multiple times a day," said Erin O'Keefe, who manages an addiction treatment program at the Howard Center's Safe Recovery.

Vermont's treatment system was designed to treat a different drug, heroin, which is difficult to find these days. The housing crisis, meanwhile, has made it harder for people in the throes of addiction to regain stability. Helping people get sober has never been more complicated or difficult.

In Burlington, the epidemic's toll has been particularly high. Overdoses are up nearly 250 percent in 2023 compared to recent years, and siren-blaring emergency vehicles race to OD scenes at least once a day. Public drug use is increasingly visible downtown and in city parks; needles and their orange caps are common sights on the ground and in green spaces. Fatal overdoses continue to climb: In Chittenden County, 29 people died from suspected overdoses through May this year, compared to 21 during the same time period in 2022.

Burlington Mayor Miro Weinberger has been vocal about the worsening drug problem and says state leaders must do more to help cities and towns respond. "We need to once again start treating this like our No. 1 public health crisis," he said.

The shifting landscape leads many to favor what is called harm reduction — helping people use drugs more safely. The logic is simple: Dead people can't recover.

But the step that many advocates believe would make the biggest impact — creating supervised "safe injection sites" — remains a nonstarter for state leaders. Until that changes, people on the ground fear, the death toll will continue to grow.

Bean, 39, who began using drugs as a teenager, has somehow survived. She spent the night in jail after her postponed arraignment. The following day, she appeared before judge Gregory Rainville via video for another hearing.

Prosecutor Sally Adams asked the judge to keep Bean in jail until she could be transferred to a residential treatment facility. Bean had overdosed "multiple times in the last week," Adams said.

"In the last week?" Rainville asked incredulously.

The judge went on to acknowledge the increasing hazards of addiction. The court system, he said, was losing people "left and right" to overdoses, including two mothers who had died in the past two weeks. "That's a little hard to stomach after a while," he said.

"I just do not expect that this woman is going to survive unless she gets treatment," Rainville said of Bean. When Bean started to argue, the judge interrupted her.

"Ms. Bean," he said, "if your life is preserved, I'll take the risk."

Rebound Effect

- James Buck

- Poster at Calahan Park

There was a time when Bean represented hope for people with opioid-use disorder. In early 2014, three weeks after Shumlin's speech, Bean was invited to the Statehouse to testify about her experience with addiction.

She'd already come a long way. As a child, Bean felt uncomfortable in her own skin — "like damaged goods," she would say years later — and the things that brought others happiness rang hollow to her. "The only time I ever felt at peace or joy was when I'm fucked up," she said.

By 30, she had been homeless or in prison for much of her adult life and experienced some of the biggest problems plaguing Vermont's treatment system: long waits at methadone clinics, a lack of access to medication for addiction in prison. But with the help of Lund, a nonprofit that works with mothers to overcome addiction, Bean had gotten clean. She was sober, housed and taking parenting classes. As she testified to lawmakers, someone held her youngest child, just 3 months old.

For the briefest moment, Bean was a voice for change.

Over the next five years, Vermont leaders joined forces to fix some of the major problems she had encountered. The health care system, law enforcement and courts slowly started to treat addiction as a disease instead of a moral failure. Treatment rapidly expanded, including into prisons.

Fatal opioid overdoses, which had risen from 63 in 2014 to 130 in 2018, finally dropped in 2019. It seemed as if Vermont had turned a corner.

But the ground was already shifting. Mexican cartels started pumping cheap fentanyl and methamphetamine into western states, and those drugs gained footholds across the Northeast, including in Vermont.

Fentanyl was showing up in more fatal overdose toxicology reports, and people who had been using cocaine for years started trying meth. Some were hooked instantly.

"I got the biggest rush I'd ever had in my entire life," said Chris, 38, of her first hit, about five years ago. "I can't even tell you how big it was. It was so much more addicting [than coke]."

Meth — or Tina, as it's known on the streets — lasted longer than cocaine, too. Chris, who asked that her last name be withheld because she still uses drugs, knew immediately she would never go back to cocaine.

"Crack is whack, but Tina pays you back," she said.

The pandemic brought new challenges. People in recovery had less contact with the support systems set up to help them stop using, and many lost jobs during the shutdowns. The social isolation led more people to use alone, which is riskier.

Fatal overdoses soared almost overnight: 158 in 2020, then 217 in 2021 — nearly doubling the figure from just two years earlier. Fentanyl and meth were increasingly found in the systems of people who'd died. Vermont's hard-earned progress slipped away.

Then xylazine, an animal tranquilizer, began popping up in the local drug supply. Users who had no idea their drugs had been cut with it began noticing unexplained wounds in places they had never shot up: their shins, faces, hands. Some reported waking up from hours-long blackouts to find they had been robbed or sexually assaulted. Narcan doesn't work on xylazine, so it became harder to bring people back from near death.

Officer John Meierdiercks joined the Burlington Police Department in fall 2021 after two years working for the Howard Center's Street Outreach Team. The rate of overdoses in Burlington seemed to take off last summer, he said. In just a few months, he responded to City Hall Park five or six times to find a man he'd gotten to know during his outreach work on the ground, not breathing. Last August, a man died of an overdose in a city hall bathroom.

The police department's data reflect the surge. Starting around June 2022, the number of overdose calls jumped, and that trend has continued. Officers responded to 49 in April alone, including 11 within one 72-hour period. And those stats don't reflect the true number. Additional ODs are being reversed by fellow drug users who carry Narcan, incidents that don't show up in the data.

The worsening drug crisis has coincided with an increase in property crime. Rates of shoplifting, car thefts and burglaries rose sharply in 2021 and 2022, driven by people who are addicted to drugs, Police Chief Jon Murad said at a public meeting last month. Vermont prison officials reported that 60 percent of people incarcerated in fiscal year 2022 were receiving medication-assisted treatment.

Bean, who relapsed not long after her appearance at the Statehouse, had become a prolific shoplifter in the years before COVID-19, but the pandemic brought her to a "whole different level." Social distancing meant store employees were less likely to confront shoplifters, and cops weren't around as much. Even people who might have had side hustles to support their addictions realized theft was a quick way to make a buck, Bean said.

Some recent violent incidents in the city have also been linked to drugs. Last summer's execution-style murder in City Hall Park, for instance, appears to have been the result of a dealer turf war, according to George, the state's attorney. Others have been tied to meth users — "people with otherwise no real violent history at all that are now dealing with some paranoia," she said.

Tyler Nolan, 32, left Burlington last summer to help care for his ailing mother. He returned this spring to a city that felt completely different.

Nolan struggled with addiction as a teenager before an arrest at 22 for selling heroin set him straight. He's been sober for a decade but has kept tabs on the drug scene, including while working at the Turning Point Center of Chittenden County in Burlington.

Downtown, Nolan ran into people he had known for years but who were hard to recognize. They appeared malnourished and had scabs on their arms and faces; some had amputated limbs.

Last month, at Calahan Park in the city's South End, where he helps coach his child's Little League baseball team, Nolan spotted two dozen used needles discarded by a dugout. He carefully gathered and disposed of them and didn't mention it when his child's teammates started arriving for their game that evening.

A week later, he returned to find posters on the dugouts instructing kids on what to do if they find a needle in the grass.

'My veins were trashed'

- James Buck

- Drug test strips at Howard Center Safe Recovery

Kelly was swimming in Lake Champlain last summer when her purse was stolen — and with it, the prescribed medication she needed to quell her opioid cravings. Kelly knew how bad things could get when she used street drugs. The last time she had relapsed, a few years before, she lost her job, then her house, and was eventually sleeping under a bridge, stealing to survive. Traumatic events had always been her trigger, and this time was no different.

"Fuck it," she said, before walking up to City Hall Park, where, within minutes, she had a bag of dope.

Kelly, who asked that her last name not be used, overdosed that day, then nine more times in a month — the start of a terrifying free fall. She was soon living on the streets, using dozens of times a day. She lost weight and stopped menstruating; her hair started falling out in clumps.

Her withdrawals became so bad that she could barely walk at times, she said, and her boyfriend would shoot her up right there in the park. "The only place he could hit me was in my neck, because my veins were so trashed," she said.

Fentanyl wears off quicker than heroin, meaning people inject it more frequently each day, at greater cost. Kelly, who lost a restaurant job once her drug use became impossible to hide, started stealing from stores to support her expensive habit, racking up a slew of charges that eventually landed her in prison over the winter.

The higher potency of fentanyl leaves less room for error, meaning users are accidentally overdosing more — and witnessing more, too. Kelly said she reversed eight overdoses with Narcan in a single month last summer.

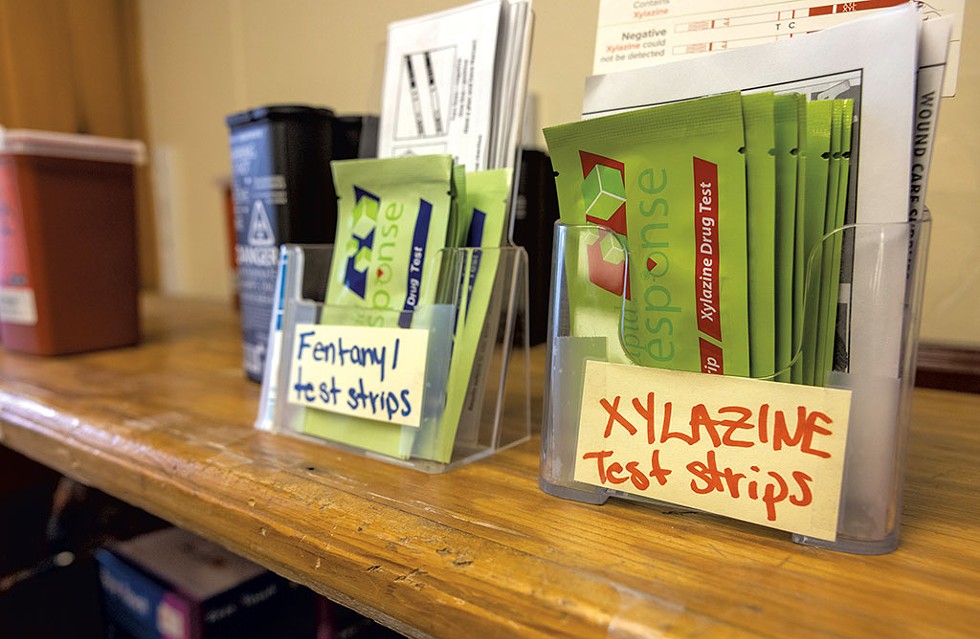

Another unknown: the potential presence of xylazine. When the animal tranquilizer first started appearing last year, people getting tested at treatment programs were shocked to discover it was in their systems. Test strips, too, indicate the presence of the sedative. Bottom line: Xylazine has become so prevalent that it's nearly impossible to avoid.

Tyler, 32, who asked that his last name be withheld, had been sober for more than two years before relapsing three months ago. Within weeks, he had sores consistent with xylazine use. Then his chest began to hurt. Thinking he had an infection, he went to the hospital, where, he said, he was told he was fine. But his condition worsened over the next few weeks, until he could barely stand. Reluctantly, he went back to the hospital a second time but left, he said, after staff treated him rudely.

"I was just another one of their drug cases," Tyler said.

He returned for a third time only after Jess Kirby, his case manager at the Burlington nonprofit Vermonters for Criminal Justice Reform, agreed to accompany him to the emergency room. He learned hours later that he had developed endocarditis, an infection of the heart that can strike intravenous drug users. Left untreated, it is deadly.

In years past, before xylazine arrived, Kirby rarely had clients come down with the infection. Tyler was her fifth to receive the diagnosis this spring.

Broken Spokes

- James Buck

- Erin O'Keefe

The "hub-and-spoke" drug treatment model was designed to integrate addiction treatment into the normal medical system. Patients in need of more intensive care would go to clinics, or "hubs," to receive medication and counseling services. More stable patients could receive their medication through primary care practices — or "spokes." This shift was only possible thanks to the addiction-treatment medication buprenorphine, which was less regulated than methadone and could be prescribed in more settings.

Over time, as doctors bought in, the model grew, and the wait lists for care that had plagued the treatment system disappeared. By 2019, more than 8,000 people — 1.2 percent of the state's residents — were in treatment for opioid addiction, giving Vermont one of the highest per capita rates in the world.

But the model, built during the heroin wave of the opioid crisis, has become less effective with today's drugs. Fentanyl is making it harder for people to transition from active use to treatment, and the state has been slow to adopt the few methods proven to help people quit meth. Meanwhile, Vermont lacks places where people can go to detox.

"Even on a good day, the tools we have to offer people sometimes feel so powerless," said O'Keefe, of Safe Recovery. "It used to feel like we could beat this thing. It doesn't feel like that anymore."

O'Keefe joined the Vermont Department of Health a few months before Shumlin's speech and spent the next five years helping to build out the hub-and-spoke system.

She realized that many people in need of help weren't getting treatment, despite the increased access. So in 2019, she took over a new program at Safe Recovery that prescribes bupe to patients who walk in off the street. The so-called "low-barrier" approach aims to bring hard-to-reach people, often homeless, into the system. And briefly, it seemed to be working.

Now, with so much fentanyl around, her program is in jeopardy; it has become too hard to transition people off the street onto bupe, O'Keefe said.

That's because of how buprenorphine works. To curb opioid cravings, bupe attaches itself to the brain's opioid receptors, dislodging whatever else is there without producing the same intoxicating effects. That can usher fentanyl users into immediate, severe withdrawal, causing anxiety, insomnia, cramps, muscle aches and diarrhea.

This phenomenon, known as "precipitated withdrawal," was less common for heroin users. As fentanyl became more prevalent and more people experienced precipitated withdrawal, word spread.

Methadone, the other approved addiction treatment medication, works differently than bupe and has become more sought-after. But it comes with different challenges. While buprenorphine has a "ceiling" at which taking more won't increase the effect, methadone does not. Significant doses can produce a high and even cause people to overdose.

It's more heavily regulated as a result, and the only place that offers it in Chittenden County — the Howard Center's Chittenden Clinic in South Burlington — requires people to show up for daily doses, at least during the early stages of their recovery.

In February, the University of Vermont Medical Center began offering methadone to people in severe withdrawal or following an overdose. But a third of the 32 people who have started the medication at the hospital since then have failed to follow up with the Chittenden Clinic the next day, a rate that Dr. Daniel Wolfson described as "not great."

There are other troubling signs. More users are taking multiple substances, including meth, and there are no medications to curb cravings of the stimulant. The few treatment programs that have shown promise — such as ones that offer incentives for sobriety — are only just starting to hit the Burlington area.

As treatment has become more difficult, the demand for places people can go to detox and regain stability has grown. But it can take weeks to get into the only two places that take Medicaid in Vermont: Valley Vista in Bradford and Serenity House in Wallingford. By the time a bed opens up, people are often back on the streets — or dead.

The lack of resources has taken a toll on both users and the people trying to help them, said Heidi Melbostad, director of the Chittenden Clinic.

"You talk to somebody and say to them, 'I hear you're unsafe. I hear you have no housing. I hear you were assaulted and raped last night. But I don't have anywhere for you to go,'" she said.

Kelly, the woman who relapsed last summer after losing her opioid medication, had a plan after her release from prison last month. But a housing opportunity fell through, so she linked back up with her boyfriend, who was camping out and still actively using.

Laying in a hammock later that night, Kelly used again. She woke up hours later to find a needle still in her arm. Her tolerance had fallen; she could have easily died.

Recalling the incident the next day, tears welled in her eyes. "I want my dignity back," she said.

Shelter-Skelter

During a record-breaking deep freeze in February, the City of Burlington set up a three-day warming shelter. Sarah Russell, who was hired by the city to help end homelessness, said staff intended to prohibit substances and people under the influence. Within 30 minutes of opening, however, Russell realized that would be impossible.

"People presented deeply under the influence, and those who were not upon arrival quickly were," she testified to Vermont lawmakers in February. Within 24 hours, two people overdosed. The first was found unconscious in a bathroom; staff administered four doses of Narcan and performed CPR until emergency personnel arrived. When the man came to, he refused to leave, saying he wanted to just lie on his cot for a while.

A couple of hours later, a man was found on the shower floor. Staff managed to rouse him, then spent 40 minutes coaxing him off the floor and into dry clothes. Russell sat next to his cot for an hour while he "vomited and cried, begging for money, drugs, methadone or death," she told lawmakers.

The experience shook her to her core. "We set out to operate a shelter to keep people safe from cold weather, but what we actually ended up doing, inadvertently, was running an overdose prevention center for three nights," she said.

The city, with the help of the Champlain Housing Trust, has since opened a community of shelter "pods" for formerly homeless people on Elmwood Avenue, where substances are tolerated so long as people don't deal drugs.

The Committee on Temporary Shelter has a different policy: Only substance-free people are welcome at its various locations, including the Daystation, a drop-in center that offers one of Burlington's only shower facilities for homeless people. Staff at the North Avenue center reported a significant increase in drug-related incidents over the winter. More people were nodding off, and more needles appeared on-site — one of which stuck a staff member.

This spring, for the first time in its more than 30-year history, the Daystation began locking its bathroom and shower room doors. Guests must now ask a staff member for access, which has helped, said Jonathan Farrell, who took over as CEO last year.

"We never wanted to get to that level," he said. "But it got so challenging — you go in, there's messes in the bathroom, there's blood spatter ... It got to the point where it was just completely disruptive."

"The best we can do is push it away," he said.

What's the Antidote?

- Colin Flanders

- Dakota Roberts demonstrating the drug-checking machine in Brattleboro

A few times a week, people head to the rectory of an old Victorian church in downtown Brattleboro and slide some drugs to Dakota Roberts. Roberts works for the AIDS Project of Southern Vermont, a nonprofit that recently launched a service to help drug users find out just what is in the drugs they buy.

"I've come to find that people generally want to be safe, and people generally want to know what they're taking," said Roberts, 30.

Drug-checking services have become more common as states seek to lower the risk of overdoses and infections. Brandeis University in Massachusetts provided the machine in Brattleboro as part of a research project to give Northeast communities insight into local drug supplies.

As overdoses increased this winter and wounds became more common, people started to show interest. The service has sampled about 65 substances to date, and Roberts expects it to catch on.

"It's amazing how interested people get in it, especially after the first time you test something for them," he said. "They have all these questions, wanting to know how it all works."

The machine shoots a beam of infrared light onto the substance and produces a signature that's mapped onto a computer program. Roberts matches the peaks of the graph to determine what substances are likely present. "This is aspirin. This is sucrose. This is heroin," he said, clicking various tabs.

Roberts needs only a tiny amount of the drugs to test either raw substances or "cooker" containers that people use to dissolve their drugs in before injecting. The process takes about an hour, and most people leave an email or a phone number so Roberts can share the results. When he does, he'll usually ask some harm reduction-themed questions, such as: Now that you know what's in there, are you going to use it in the same way?

The work has helped Roberts understand how much the drug supply has changed. Fentanyl used to be mixed into heroin, he said. Now, almost every sample contains just fentanyl, mixed with a basic cut — usually mannitol, a cheap diuretic.

He's also started to notice that the weirder colored the dope, the more likely there's xylazine present. "Traditionally you were looking at, like, white, off-white powder, maybe brown when heroin was still big," he said. "Now you're seeing yellow, green, blue, purple."

Related An Innovative Drug-Treatment Program Encourages Sobriety With an Incentive: Cash

A new law in Vermont will provide legal protection to anyone running drug-checking services, which could pave the way for more. It's one of a handful of measures included in a bill that Gov. Phil Scott signed late last month aimed at lowering drug overdose deaths.

That bill, H.222, also includes the first wave of spending from Vermont's share of funds from national legal settlements with opioid manufacturers: $2 million to fund 26 new outreach and case manager positions; $2 million to distribute Narcan, including through public kiosks or vending machines; $2 million to create four new satellite methadone clinics; and nearly $1 million to expand promising treatment programs that use financial rewards to encourage sobriety.

One thing the bill does not touch on: overdose prevention sites, which have been proven to reduce OD deaths in places where they've opened. Two now operate in New York City, and many view the strategy as the best way to curb the fatality rate in Vermont. That includes Weinberger, who noted that 75 percent of all people dying from fatal overdoses in Vermont have never been treated for addiction.

"That's a staggering figure, and, to me, says that we are absolutely missing a large majority of the people that are most at risk," Weinberger said in an interview.

But Gov. Scott has long opposed overdose prevention sites, going as far as to veto a bill in 2022 that would have simply created a study of them. And Health Commissioner Mark Levine has expressed doubt that the facilities would work in Vermont due to its rural landscape.

At a legislative hearing in April, Levine raised concerns over geographic equity, noting that some of the highest overdose rates occur in rural areas where it could be difficult to staff such a site. He also questioned the pragmatism of the facilities in the age of fentanyl, when people have to use more often. Someone would have to "live" at a site to stay safe, he said, adding that he wants to see more research.

Levine's testimony incensed harm-reduction advocates such as Ed Baker, a 76-year-old former injection-drug user in Burlington who has become one of the most vocal supporters of safe injection sites.

While it's true that most overdose deaths occur outside of Burlington, that's not a good reason to stand in the city's way of starting one when both local officials and community organizations support the idea, Baker said. And even if someone uses the site only once a day, that's one less time they're at risk of dying, he said. Isn't that worth it?

Baker thought that Vermont officials had begun to finally treat addiction like the disease that it is. But the refusal to reconsider stances on safe injection sites signals otherwise, he said.

"We've changed our language, but in here," he said, pointing to his heart, "in here, we still don't care if they die."

Weinberger shares Baker's frustration and said he fears that the state is no longer treating the problem as an urgent matter. Back in the mid-2010s, then-governor Shumlin practically begged local leaders to help fight opioids. Now, Weinberger said, he and his counterparts are pleading for help from the state.

"If we want to really address this crisis," he said, "we need state government to again be a true partner."

'You're Alive'

Amanda Bean was angry the first time she was revived from an overdose — not because she wanted to die, but because she had found a momentary peace in the thought that her disease might finally stop hurting those around her.

She has come to realize the flaw in her logic. Even now, at her lowest point, she still has people in her life who believe she can be rehabilitated: her father, for one, who has stepped in to take care of her children. He has found ways to forgive her time and again.

"'At least I know where you are and that you're alive,'" she said he told her last month when she called from jail, a conversation the two have had many times over the years.

Per judge Rainville's order, Bean remained in jail as this story went to press; the state was looking for a treatment bed.

She said her attorney was trying to secure a plea deal that would allow her to resolve many pending charges in exchange for a one- to four-year prison sentence that would be deferred, as long as she participated in treatment court. From there, Bean hoped to get into Jenna's Promise, a center in Johnson launched by the parents of Jenna Tatro, who died of an opioid overdose in 2019 at age 26.

The nonprofit runs a residential treatment program for women and allows people to stay for up to a year, much longer than the typical 14 days at Vermont's other rehab centers. According to Bean, her father told her, "I think it could change your life."

The center only has space for 17 women at a time, however, and the spots are in high demand. Bean has been in touch with the center's staff and said she believes she'll get in. She has to, she said, because the alternative — landing back on the streets — can only end one way.

"I'll be dead."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.