- Tim Newcomb

Gov. Phil Scott has earned praise for following the guidance of public health experts as he leads Vermont's response to the coronavirus pandemic. Nearly every opportunity he gets, he notes his reliance on data and science.

But when it comes to the peril posed by a rapidly warming planet, environmental advocates argue, Scott has failed to take seriously what experts have made clear for years.

"The science says that we have an urgent crisis on our hands — that we have to reduce pollution dramatically," said Johanna Miller, energy and climate program director at the Vermont Natural Resources Council. "We're not doing our part in Vermont. We're not following the science when it comes to climate."

Criticism of Scott's environmental record mounted last week when he vetoed the Global Warming Solutions Act, which would require the state to reduce its carbon emissions and allow residents to sue if it fails. The House quickly overrode his veto, and the Senate did so on Tuesday.

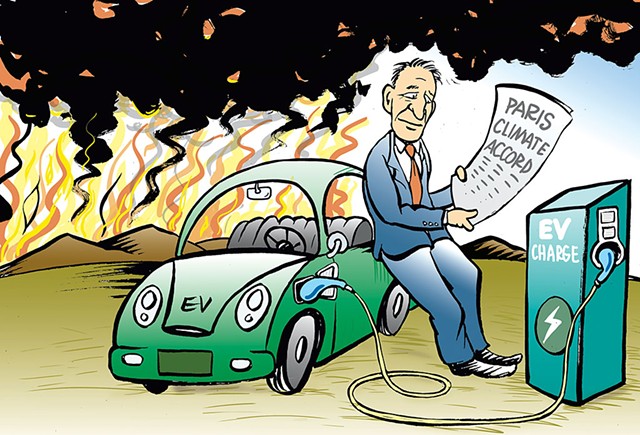

"It was pretty appalling to see this veto come when significant chunks of the West Coast are on fire and the Gulf Coast is underwater," said Ben Walsh, climate and energy program director for the Vermont Public Interest Research Group. "There couldn't be a more stark reminder of why action is necessary — and immediately necessary."

Even Rep. Laura Sibilia (I-Dover), a close ally of Scott's, spoke out against the veto during last week's House override vote. "I am a big fan of our governor," she said on the virtual floor. "He is wrong."

Scott, a Republican who is seeking his third two-year term this November, remains immensely popular with the electorate. According to a new poll released this week by Vermont Public Radio and Vermont PBS, he leads his Progressive/Democratic opponent, Lt. Gov. David Zuckerman, 55 to 24 percent. But the governor's environmental record — or lack thereof, as some see it — stands out as a potential vulnerability. That could explain why his campaign has taken out advertisements on Facebook to burnish his climate bona fides.

"Governor Phil Scott: Leading on combating climate change and preserving our environment," the ad reads, highlighting his work to invest "millions to lower emissions and increase energy efficiency."

According to Zuckerman, a longtime environmental advocate, "That ad screams of 1984 Orwellian doublespeak." The way he sees it, Scott's record has never matched his rhetoric. "He's talked about the climate many times, but the scale of many of his proposals [is] paltry compared to the urgency of the moment," Zuckerman said.

Scott's critics fault him for opposing wind power generation, proposing cuts to clean energy and efficiency programs, and vetoing two bills that would allow Vermonters to sue polluting companies for medical monitoring costs. They also worry he'll refuse to sign off on the Transportation and Climate Initiative, a regional compact that would effectively raise the wholesale price of gasoline and diesel fuel and invest the proceeds in clean energy.

"Despite the fact that he says he believes climate change is real and Vermont has to do its part, he just hasn't shown a lot of leadership or willingness to do much beyond the status quo," said Rep. Sarah Copeland Hanzas (D-Bradford), who cochairs the legislature's Climate Solutions Caucus. "It's perplexing and disappointing."

Scott drew headlines in June 2017 when he committed to meeting the carbon emissions goals of the Paris climate accord after President Donald Trump began the process of withdrawing the United States from the international agreement. The governor quickly joined the U.S. Climate Alliance, a coalition of states and territories that pledged to meet the pollution targets, and he convened his own Climate Action Commission to come up with a plan to do so.

In July 2018, the commission sent Scott its final report, which included 53 recommendations ranging from doubling state funding for weatherization of low-income housing to encouraging carbon sequestration on Vermont's farms. According to Environmental Conservation Commissioner Peter Walke, who cochaired the commission, the administration has been working to implement those recommendations ever since — focusing particularly on increasing the use of electric vehicles.

"There's all sorts of things happening," he said. "All of these things are going to build together to create the scale we need."

Miller, who also served on the commission, credits the governor for making "incremental progress" but argues that "any of the recommendations that require a significant scale are not being implemented." In her view, the commission was hobbled from the start because the governor made clear he would not accept any proposals that would require new taxes.

"There was never any opportunity to think bigger and bolder or to talk about how we might shift investments or raise new revenue," Miller said. "This transition is going to require us to do things differently."

It's too soon to know whether the Scott administration has had any success in reducing Vermont's carbon emissions, because accurate data take years to collect. But at the time he took office four years ago, the state was nowhere close to achieving the Paris goals: the most immediate target being a 26 to 28 percent reduction below 2005 emission levels by 2025.

According to a report issued in January by Walke's Department of Environmental Conservation, Vermont had notched just a 5 percent reduction by 2016 — the least progress of any state in the region. Moreover, the report found, Vermont had higher per capita emissions than any other state in New England.

Asked last week whether he believed his administration's actions would ensure that Vermont met the goals of the Paris accord, Scott said, "We'll see ... I know that's not a great answer, [but] I do think the technology needs to catch up." Later in the interview, he conceded that the state "may miss" its 2025 targets. "I don't know," he continued. "Obviously we'll keep the focus on that and try to maintain and hit our targets, but I think the trajectory isn't linear. It's going to be somewhat level until technology catches up."

Walke voiced an even more pessimistic view. The debate over the Global Warming Solutions Act, he said, "was a clear recognition that we are not on the path that we need to be on. We wouldn't need a planning effort right now if we were going to get there."

While Vermont has successfully reduced carbon emissions generated by its electricity sector, it continues to see increases in transportation and building thermal emissions. According to the DEC's January report, transportation alone accounts for nearly 45 percent of the rural state's emissions.

For that reason, Scott speaks frequently about his desire to replace gas-guzzling automobiles with electric vehicles. "I'm really excited about EVs," he said in the interview. "I think that's where we make significant gains."

The state certainly has a long way to go. As of January, according to the Department of Motor Vehicles, only 1,600 all-electric vehicles and 2,116 plug-in hybrids were registered in Vermont. Experts say the state needs 50,000 to 90,000 EVs on the road by 2025 to meet its carbon reduction targets.

In his January budget address, the governor proposed investing $3 million more in electric vehicle incentives, education and infrastructure build-out. But last month, during an unusual midyear budget rewrite, his Agency of Transportation recommended cutting $700,000 of that.

Speaking last week to the Senate Transportation Committee, VTrans director of policy, planning and intermodal development Michele Boomhower explained that the program was "just not well-timed" due to financial constraints caused by the pandemic. The money, she argued, should go to paving projects instead. "Although we are very much in support of [EV incentives], we feel as though those could wait another year," she said.

Asked about the apparent contradiction between his words and actions, Scott said, "We're in a once-in-a-century crisis right now — economic and health crisis — and we have to be realistic."

According to Lauren Hierl, executive director of Vermont Conservation Voters, it's a mistake to think that the state must choose between addressing the coronavirus crisis and the climate crisis. "I think Vermonters can walk and chew gum at the same time," she said. "We can't pick and choose when we listen to science and when we prioritize issues. We don't have time to lose."

Hierl's organization has endorsed Zuckerman, as has 350.org, the Vermont Sierra Club, VPIRG Votes and the environmentalist Bill McKibben. The lieutenant governor has pledged to raise taxes on the highest-earning Vermonters and invest tens of millions of dollars in weatherization, renewable energy generation and other priorities.

In recent months, Scott has made his respect for science a theme of his reelection campaign. Ahead of this summer's primary elections, he criticized Zuckerman for expressing skepticism about vaccination research during a 2015 legislative debate. But the governor's acceptance of long-established climate science is even more newfound than that.

When he first ran for governor in 2016, Scott repeatedly suggested that humans might not be entirely to blame for the warming of the planet, echoing discredited industry talking points. "Climate change is happening," he wrote in an online forum that July hosted by Reddit and Vermont Public Radio. "And I believe as well it is a combination of man-made contributions as well as a natural phenomenon."

In an interview with Seven Days the next month, Scott walked back his assertion, saying his views had evolved and he had come to understand that climate change is, in fact, due largely to the actions of humans. In last week's interview, he attributed that evolution to the research becoming "more conclusive," though it has been the scientific consensus for decades. "I do listen to the science and the data, and it's become clear that it's man-made," the governor said.

Scott has also argued that Vermont could benefit from the ravages of a changing climate. During a December 2017 press conference, he said that the spate of wildfires threatening California at the time "makes Vermont look pretty good" and could bolster his own state's economy. The remarks prompted U.S. Rep. Ted Lieu (D-Calif.), whose Los Angeles district was scorched by the fires, to issue a press release calling Scott's words "insensitive and stupid."

In last week's interview, Scott acknowledged that his 2017 remarks were "fairly callous" — and even more so now, given the death and destruction of this year's wildfire season. "I regret the way I portrayed that," he said. "But at the end of the day, I think people are going to make decisions on how they can be more safe and healthy."

Scott also defended his recent veto of the Global Warming Solutions Act, drawing an unexpected comparison to a statement he issued arguing that the late U.S. Supreme Court justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg should not be replaced until the next president takes office. "I think what people have to understand is that I believe in process," he said. "It's not about the bill itself or climate change. It's about process."

In Scott's view, the Global Warming Solutions Act is unconstitutional because it empowers an unelected board to determine how the state should meet its carbon emissions goals.

"I think this sets a dangerous precedent," he said at a press conference last week, calling it "suspect" that such a bill would reach his desk at the height of election season. "I do think it has political overtones."

Scott's critics hope it will also have political consequences.

Correction, September 23, 2020: An earlier version of this story misstated the percentage of Vermont's carbon emissions attributable to the transportation sector.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.