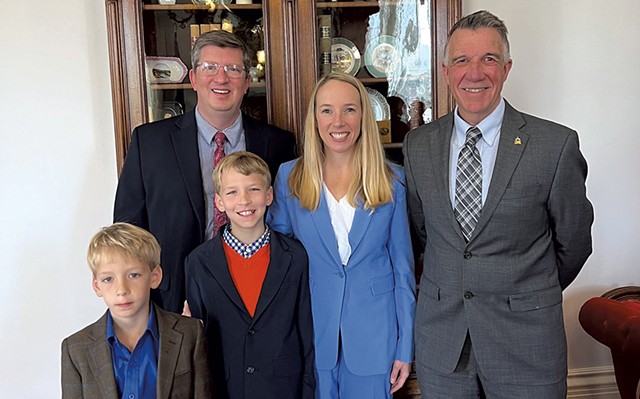

- Courtesy Of Gov. Scott's Office

- Gov. Phil Scott and the Saunders family

Late last month, Gov. Phil Scott held a press conference to introduce his long-awaited choice for Vermont education secretary: Zoie Saunders, a Florida school administrator.

"She's a problem solver, leader and innovator who's been laser-focused on improving outcomes for kids," Scott told those assembled.

On the social media platform X later that day, the governor posted a photograph of himself, Saunders, her husband and two young sons, calling Saunders "an experienced public-school leader."

But Scott's choice has met forceful pushback. Residents, lawmakers, the state teachers' union, the Vermont Principals' and School Boards associations, and even the Democratic and Progressive parties have all raised concerns about Saunders' qualifications for the $168,000-a-year leadership position. She has never worked as a teacher, principal or superintendent and has held her most recent job, as chief strategy and innovation officer in Broward County Public Schools, for just three months.

Saunders' critics have zeroed in on her seven-year stint as a strategist for Charter Schools USA, a privately held, for-profit charter school management company that runs more than 90 schools in five states. They say those schools, which are not currently allowed in Vermont, circumvent public oversight, siphon off tax dollars and are antithetical to the system of education in the Green Mountain State.

At a press conference last week, Scott said the topic of charter schools didn't come up in the interviews he conducted with candidates. The governor also said he doesn't want to start charter schools in Vermont.

Myriad challenges — rising costs, declining enrollment, acute mental health needs, a persistent teacher shortage, lagging academic skills and aging infrastructure — make the appointment of a knowledgeable and capable secretary of education more important than ever, school leaders say. The Agency of Education, which has been without a permanent secretary for a year, is in dire need of a visionary chief executive capable of boosting a demoralized workforce that lacks a clear sense of purpose, according to several agency employees Seven Days interviewed last week.

The backlash to Saunders' selection has put the governor on the defensive. He issued a fiery press release in support of her one week after the introductory press conference. Last Thursday, five senior members of his administration released a commentary titled "We're Moms. Our Kids Are in Public School. We Helped Select Zoie Saunders as Vermont's Next Education Secretary." The women, members of the interview team, said Saunders' "strategic thinking" and experience working with schools in multiple states would be assets to Vermont.

Saunders is slated to start on April 15, but she must be confirmed by the state Senate. The body's Education Committee is scheduled to hold hearings later this month. A majority of senators have to vote for her appointment.

In an interview with Seven Days last Friday, Saunders said she understands that Vermonters have a lot of questions about her. But with the skills acquired in previous jobs, she believes she can help create and realize a vision for Vermont schools. Saunders stressed the importance of using data to drive decisions while also working with individual communities. During the 40-minute interview, she was personable and open to answering questions but employed lots of educational jargon to make many of her points.

"I'm looking forward to being on the ground so I can have those open lines of communication and really listen and learn so I can be an effective leader for the state," Saunders said.

To examine her work experience, Seven Days reviewed news articles and school board meeting recordings from Florida and interviewed national experts on charter schools.

One of those experts, Florida resident Bruce Baker, knows Vermont well. He grew up in Rutland and coauthored Vermont's 2021 pupil weighting study — an analysis of Vermont's funding formula that led to far-reaching state aid changes. He also authored a 2015 policy brief, "When Is Small Too Small?," that examined the efficiency of Vermont's schools.

Baker said he doesn't see how Saunders' experience is relevant to Vermont's education system.

"I wouldn't be surprised by [Saunders' selection] in a number of other states," said Baker, who chairs the department of teaching and learning at the University of Miami. "But Vermont making this choice, I just don't understand it."

'Enhance Their Bottom Line'

When charter schools started in the 1990s, they were billed as places of learning that would allow teachers to innovate and experiment. They could be more flexible than traditional public schools, unfettered by requirements around such things as curriculum, transportation and the number of school days each year. Both Republicans and Democrats largely supported them.

Charter schools are privately run but funded with public dollars. They offer free tuition and cannot set special entrance requirements. To open, charter schools must be approved by an "authorizer" — typically a local or state school board or state education agency.

Roughly 8,000 charter schools now serve around 3.7 million American students, or 7.4 percent of all public-school pupils. Florida is among the states with the highest number, while Vermont is one of only five states that do not allow charter schools. Proponents of charter schools say they give families more choice in how their children are educated.

Carol Burris, a former principal in Long Island, N.Y., and executive director of the Network for Public Education, said charter schools operate very differently than do public schools in Vermont. Her group advocates for strengthening public education and seeks legislative reform of charter schools.

"What charter schools lack is public governance," Burris said. "Public schools are democratically governed by the public. People elect their neighbors to govern the schools." Charter schools, in contrast, are governed by board members who are appointed, in most cases, by school leadership or the company that runs them.

Charter schools have changed substantially in the decades since they were created. Some are now run by education management organizations — for-profit companies. Charter Schools USA, where Saunders worked as a strategist from 2012 to 2019, is one of the largest EMOs in the country, responsible for more than 90 schools in Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina and Louisiana.

Its CEO and founder, Jon Hage, also runs Red Apple Development, a real estate company that buys land and builds schools, then leases those facilities to charter schools. Charter Schools USA is then hired to operate them.

Charter schools use public dollars to pay rent to Red Apple and management costs to Charter Schools USA. Hage also owns a variety of other businesses that receive taxpayer dollars and earn contracts from the Charter Schools USA network.

During her interview with Seven Days, Saunders distanced herself from that aspect of the company. In her role, she said, she focused on helping schools support students to improve their performance, "not the broader corporate entities." One of her proudest accomplishments at the company, she said, was developing a digital platform that helped teachers make data-driven decisions about students.

Saunders said she helped run schools in multiple states, which is relevant to Vermont's ethos of local control. Communities "had different local priorities, and so it was imperative to respect and honor those local traditions while still establishing high-quality standards across all schools," she said.

But Burris, the public-school advocate, said she was troubled by Saunders' "choice to begin a career in education not as an educator of children but as a strategist for a privately run corporation that extracts profit by minimizing what they spend."

Several Florida communities raised similar objections when Charter Schools USA came to town. In 2017, the Marion County School Board denied the company's attempt to open a K-8 school. The district superintendent told board members that she believed Charter Schools USA officials did not "have the best interests of our students at heart" and that "they want to take advantage of our students to enhance their bottom line."

In 2022, the Sarasota County School Board unanimously denied the company's request to open a high school in the city. "This is not the caliber of school that belongs in our district," a board member said at the time.

Looking for a Partner

- Courtesy

- Zoie Saunders

In 2019, Saunders left Charter Schools USA to work as the City of Fort Lauderdale's chief education officer, a newly created position.

Saunders said she was hired to partner with schools and other entities to create greater educational opportunities. One of her major accomplishments, she said, was in the aftermath of the pandemic, when she used federal funds to help develop a summer enrichment and afterschool program to address learning loss.

Saunders found herself in the middle of a heated debate in 2022 when the district considered a partnership with Bezos Academy, a network of Montessori-inspired private preschools started by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos. Bezos Academy wanted to offer tuition-free, full-year preschool in exchange for 10 years' rent-free space in public school buildings.

At a Broward County Public Schools meeting, Saunders offered the city's "strong support" for the plan.

"The Bezos Academy partnership accelerates and expands our capabilities together to address the need and prepare more children for success in schools," Saunders said, noting that it would improve the low kindergarten readiness in public schools.

Teachers' union leaders vociferously objected, calling the plan "Outsourcing 101." They expressed concerns about transparency and oversight, as well as fears that the Bezos schools could negatively affect the public schools that housed them. School board members, too, were skeptical about supporting a private initiative within the public school system.

"I think that we need to cue the wild clown car if we support this item because every door is going to be knocked [down], and it's not going to be a very pretty thing for public education," one board member said.

The partnership did not go forward.

Last December, Saunders was on the move again, taking an $180,000 job as chief strategy and innovation officer in Broward County Public Schools. Saunders said the role built on work she had already been doing in Fort Lauderdale.

Saunders' main focus was to lead Redefining BCPS, an initiative to close or repurpose schools amid declining enrollment. During her brief tenure, Saunders helped organize three "community conversations" meant to collect ideas and feedback from residents about potential school closures.

At the first, attendees answered questions posed by the district about school closures using an artificial intelligence-powered platform called ThoughtExchange. Then "they got to up-vote or down-vote other attendees' ideas," the Miami Herald reported. One teacher told the Herald that the process was "bizarre" and did not allow for "deep, raw conversations."

Saunders said she is proud of the "participatory process" she helped develop to engage community members. It's critical to use "a mixed methodology" when doing this type of work, she said.

"I think it's really important to offer a lot of different ways for people to engage in the discussion," she said, including through surveys, focus groups and grassroots efforts.

But Narnike Pierre Grant, chair of the Broward County Public Schools' diversity committee, said she wasn't impressed by the process. In an interview with Seven Days, Pierre Grant said she felt Saunders was pretending to listen when the district had already decided which schools were on the chopping block. While Pierre Grant found Saunders to be pleasant in their interactions, she said she felt the school exec was disingenuous about the purpose of her role with the district.

Pierre Grant said she was also upset that Saunders came into Broward County, initiated a contentious process and is abruptly departing.

"She doesn't have to deal with the aftermath," Pierre Grant said. "It's really a kick in the teeth to know she's come here, set some things in motion ... and she leaves in the middle."

Nathalie Lynch-Walsh, chair of the Broward County Public Schools' facilities task force, said she didn't think Saunders had enough experience for the complex job for which she'd been hired in Broward County. She noted that her district has faced a rocky few years: A superintendent was arrested, four school board members were removed from their posts by Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis and, just last month, the state ordered the district to pay $80 million to charter schools to settle a lawsuit. Among those who sued the county: Charter Schools USA, Saunders' former employer.

Lynch-Walsh said it was hard to assess how Saunders did in the Broward County job because "she wasn't here long enough to even get her toes wet."

Committed to Public Education?

Saunders said she knows Vermont's education system is facing big challenges but believes she's well suited to tackle them.

On rising education costs, Saunders said she has experience working with cash-strapped schools to come up with processes to cut expenses "in ways that are going to have the best outcomes for students."

As for consolidating or closing schools to bring down costs, Saunders said her work in Broward County prepared her for those discussions.

"What I have learned is, it's not a one-size-fits-all solution, and it's very important for these conversations to be data-driven and also incorporate local input," she said.

Asked about the thorny issue of public money going to private and religious schools through Vermont's tuitioning program, Saunders said, "The state has to follow the federal law." She acknowledged that she has much to learn about the "role that both the public and independent schools play" in Vermont's education ecosystem. But she believes the state is taking the right approach by making sure all schools have strong antidiscrimination policies "so that students are all feeling supported, loved and valued."

Saunders' two sisters and aunt live in Vermont, and her mom just bought a house in the state and plans to retire here. The opportunity to be closer to family is "personally meaningful," she said.

But to get confirmed, Saunders needs to convince a majority of senators that she's the right person for the job. Sen. Becca White (D-Windsor) is one of them.

White said she's been surprised by how much feedback she's received from educators and parents who are concerned about Saunders' former employment with a for-profit charter school company. Constituents rarely reach out to her about the governor's picks for secretaries, commissioners or judges, White said, but she's been getting roughly 10 emails a day. People want assurance, she said, that Vermont's next secretary of education is committed to safeguarding public education.

"When I look at the résumé we have for Ms. Saunders, I have concerns because the public education part ... is the shortest and most recent part of her experience," she said.

Still, White added, she will approach the confirmation process with an open mind.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.