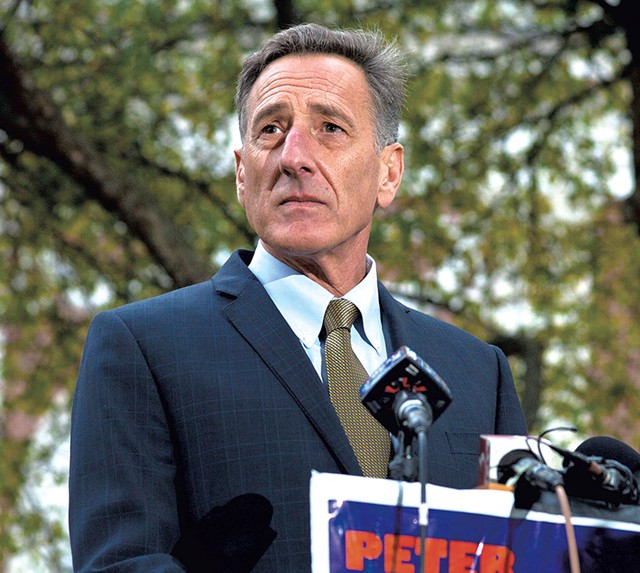

- Matthew Thorsen

- Gov. Peter Shumlin

Peter Shumlin didn't want to do this. He didn't want to sit for an exit interview and talk about the highs and lows of his six years as Vermont's governor.

After several pleas — he had to do it for history's sake, I argued — the departing Democrat acquiesced to an hourlong sit-down in his office.

I took his reluctance as an indication he's tired: tired of getting beat up by journalists and on social media, of the constant rehashing of his missteps, of the trappings of the high-profile 24-7 job.

I had watched Shumlin — literally — as he walked into the governor's office in January 2011, after I covered his campaign and his previous four years as Senate leader. He was a wiry, upbeat Energizer Bunny of a politician with but a wisp of gray in his hair. Now 60 years old, he has bags under his eyes, lots of gray and a been-there, had-enough look about him.

He's had successes as governor, most notably leading the state's recovery from Tropical Storm Irene and drawing national attention to opiate addiction.

But there have been some rough stretches: Technical problems plagued his highly touted state-run health insurance exchange, and financial scandal rocked the Northeast Kingdom development projects he championed.

Somewhere around the halfway point of his time in office, he went from courting the news media to treating us like an untrustworthy adversary. He grew distant from a legislature dominated by his own party. Once Mr. Fun, he no longer seemed to be having any.

But no, Shumlin insisted as we launched into the legacy interview, he wasn't looking to avoid this discussion because he's tired of the media or the job.

"I'm not big on legacies," he said. "I'm not one that looks back."

That's true, according to those who have worked with him. "He's a forward, not a backward, looker," said Liz Miller, a lawyer who served with Shumlin for four years — as his public service commissioner and then as chief of staff.

But six years as governor have changed Shumlin. What happened to that guy who was so eager to be governor of Vermont?

Growing up in Putney, Shumlin took to politics early on. He listened to Martin Luther King Jr. speeches on reel-to-reel tape in the closet of his childhood bedroom. As a dyslexic boy who struggled to read, he learned to shine thanks to his gift of gab.

Over three decades, he worked his way up from the Putney Selectboard to the Vermont House and Senate, where he served two stints as president pro tempore.

In a come-from-behind 2010 campaign, he out-hustled four Democratic primary opponents and then Republican Brian Dubie to win election.

He promised to get "tough things done," and many of them he did.

As a legislator, he had a reputation for being a bull in the china shop, ticking off a lot of people and then charming his way back into their good graces. He was a driving force behind Vermont's same-sex marriage law and the fight against pharmaceutical companies.

As governor, he remained true to that style — but every accomplishment seemed to offend somebody, and he couldn't possibly charm everyone back. His renewable energy push provoked outrage from a growing cadre of wind-power opponents. His support of the Addison Natural Gas Project pipeline riled environmentalists.

Persistent problems with the state's health insurance exchange, Vermont Health Connect, suggested he couldn't get tough things done — at least not this particular mega-million-dollar IT project that was outsourced to a vendor that went belly-up.

When he dropped plans for a single-payer, government-financed health plan after barely winning reelection in 2014, he lost some of his most ardent liberal supporters.

So it is that the man who strove to be governor now talks wistfully of repairing to Putney with his wife of one year, Katie Hunt, whom he described as his "sanctuary of sanity." He pines for people to call him "Peter" again instead of "governor."

He may not like to look back, but I know I'm not alone in wondering: How will Shumlin be remembered as Vermont's 81st governor?

After our interview, I ambled over to the Statehouse steps to watch him light the Christmas tree. On the chilly December evening, parka-clad toddlers darted through their parents' legs.

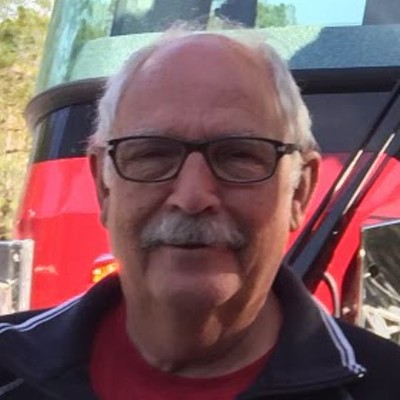

Michael Obuchowski, the mustachioed commissioner of state Buildings and General Services, introduced Shumlin. Disregarding the crowd's eagerness to see the lights come on — and to sample the hot chocolate that awaited — Obuchowski talked briefly about his boss.

History, he said, would look kindly on Shumlin as one of the most effective Vermont governors.

"He took on unpopular things or things that were difficult to do politically," Obuchowski explained later. "He went by a maxim that it's better to try and fail than to not try at all."

Many of Shumlin's boldest moves have yet to yield fruit, Obuchowski said, citing the governor's work boosting opiate treatment and limiting doctors' ability to overprescribe.

Miller made the same point about Shumlin's work establishing universal access to prekindergarten programs. "That's a big deal," she said. "It's going to take time to develop, but it's going to matter."

Shumlin's friends and foes agreed he's been an aggressive governor.

"Vermonters were looking for perhaps a more activist governor. That's what he's done," said Bill Lofy, who served as Shumlin's chief of staff his first two years in office. "He understood his political capital would start to diminish the day after he took office."

Shumlin was too active, argued Rep. Heidi Scheuermann (R-Stowe), who said she's suffered from both the cost and complications of buying insurance through Vermont Health Connect.

"He wanted a chicken in every pot, free health care for everybody," she said. "I don't think he set the expectation at the right level."

"That's the curse of the liberal Democrats — they want to do things," said Steve Kimbell, who worked for Shumlin on health care reform during his first two years in office.

Kimbell, like others who know Shumlin well, said the governor was undaunted by risk. "He's a little too self-confident for his own good," Kimbell said.

Shumlin, when asked recently about his willingness to fly in the state's 1962 Cessna, said he has always lacked the "fear gene." It's an apt analogy for how he reacts to most things, Kimbell said.

More caution might have served Shumlin back in 2013, when the governor plunged into a deal to buy his cognitively impaired next-door neighbor's house. Jeremy Dodge's friends cried foul, saying that Shumlin took advantage of him.

Shumlin claimed he was trying to help Dodge, who was about to lose his home to foreclosure. But public outcry forced the governor to undo the deal and to become Dodge's mortgage holder. Shumlin argues that it's all worked out. Dodge still lives in the house and is making good on his obligations.

But the episode plagued Shumlin, reinforcing Vermonters' uneasiness with his sometimes cavalier style.

"Whether it deserved to or not, it captured a feeling people had," said departing House Speaker Shap Smith (D-Morristown).

Smith argued, as Shumlin did, that the Dodge deal should not be remembered as a defining element of Shumlin's tenure.

But the controversy did coincide with the decline of Shumlin's popularity. During the 2014 campaign, voters repeatedly referred to it as they tried to put their finger on why they'd lost faith in Shumlin. The two-term incumbent came within roughly 2,400 votes of losing to a Republican novice, Scott Milne.

The Dodge controversy also seemed to change Shumlin's relationship with the media. He became a less enthusiastic interviewee; he stopped trying to charm us.

Shumlin dismissed my reasoning. "I love the media," he told me, as if saying so made it true. His wife was less diplomatic. When he started dating Hunt, who is half his age, the Vermont press held off revealing the relationship until the couple started showing up together at official events. Nonetheless, she took aim at various Vermont media outlets in a series of papier-mâché sculptures that Shumlin displayed in his ceremonial Statehouse office in June, after the legislature adjourned.

Those who know Shumlin say neither the Dodge deal nor any single event was the trigger, but that Shumlin did face a lot of negativity that, over time, became increasingly fierce.

Society changed, said Alex MacLean, who was Shumlin's campaign manager in 2010 and then served as his deputy chief of staff for three years. Her former boss was the first Vermont governor to feel the brunt of social media's harshness, she said. Everything he said and did unleashed a torrent of dismissive critics.

"It's brutal to be a public official in this day," she said. "You have people hiding behind their computers saying anything."

While Shumlin's relationship with the public and the press may have changed, staffers said, he went about his business the same as ever. He did not dwell on what people thought of him.

"The governor, from my experience, really remained focused on what he wanted to accomplish," Miller said. "He said it from the moment I was hired: 'Time is short, and we've got a lot to get done.'"

Shumlin lays claim to a sizable list of accomplishments. He reeled them off without the help of notes, declining to characterize any single one as most significant. "All of them," he said.

"We delivered on almost every single vision we had," Shumlin said, leaning back in a wooden office chair with his feet up on another chair.

He had pledged to shut down Vermont Yankee. In 2014, the nuclear power plant closed, though its owners said it was the market, not the governor, that forced their hand.

"They said the lights would go out" when Yankee closed, Shumlin said. Instead, Vermont has the second-lowest electric rates in New England.

He had pledged to expand renewable energy, and on his watch the state saw a boom in wind and solar projects. In the last year, Vermont has gotten 1,400 new clean-energy jobs, Shumlin maintained, bringing the state's total to 17,000.

Even on health care, for which he has faced the most criticism, Shumlin cited progress. The number of uninsured Vermonters dropped from 8.6 percent of the population to 2.7 percent, though some of that decline can be attributed to the federal Affordable Care Act. The much-anticipated "all-payer" payment model he negotiated with the federal government could finally bend the curve of health care costs, he contended.

One of Shumlin's most acclaimed achievements came after Tropical Storm Irene hit in August 2011, eight months into his first term.

The storm killed six Vermonters, shredded hundreds of miles of roads and bridges and flooded the state government's largest office building in Waterbury.

Shumlin won credit for both his emotional and logistical responses. He was consoler in chief for those who lost homes and family. He was clerk of the works in rebuilding roads and offices.

"His response to that crisis will be seen as one of his finest hours," Smith said. "He was unwilling to let people say, 'We can't do this; we can't rebuild.' There are a lot of people who would not rise to that challenge."

While Irene might have been a political high point for Shumlin, he rates it as his toughest situation. Never mind the grief he got over Vermont Health Connect, he said. It was far more difficult to deal with the real grief he saw at the funerals of those who were swept away in the storm.

"I don't think you can prepare for that kind of unexpected tragedy," he said. "You're supposed to be the one who can fix it."

How has that burden changed him? I asked.

"I'm more sober," he said, "about how tough it is to get tough things done."

Comments (6)

Showing 1-6 of 6

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.