- Annelise Capossela

Last spring, 27-year-old Lauren Weston quit her job as a water resource engineer at Milone & MacBroom in Waterbury and moved to a yurt on a farm in Franklin County. Over the last decade, the path from the corporate world to the yurt has seen plenty of millennial foot traffic, but Weston's reasons for abandoning her nine-to-five existence reflect a cultural undercurrent that has only recently entered the mainstream lexicon: climate panic.

It has other names, too — ecological anxiety, climate anxiety, climate grief, ecological grief — but each of those labels refers to the same malaise: a growing sense that everything is hurtling toward cataclysm, that we've trapped ourselves in a hell of our own making.

If you find this story alarming, you’re not alone. This month, Seven Days is launching a semi-regular series called “Fired Up: Vermonters respond to the climate crisis.”

We’ll explore the state’s climate-related challenges and what residents are trying at a local level to mitigate the planet’s heating trend — noting what’s catching on and what isn’t. We’ll also look at ways to become more resilient in the face of changes that may be inevitable.

All of these stories will be tagged with the Fired Up icon. Look for them in upcoming issues.

Got a suggestion for the series? Send it to coordinator Elizabeth M. Seyler.

Weston interned on the farm for six months, an experience she described as transformative and humbling. "I had no idea about how crops grew, or the timing of seasons," she said. At night, she liked to hear the animals rustling in the woods outside her yurt.

But since the internship ended and she moved to Burlington last fall, the despair has crept back in. Weston won't attend events that require her to drive; this year, she stayed home alone on Thanksgiving, because she didn't think she could bring herself to make small talk with anyone. Sometimes, Weston said, the only thing she can do is lie on the couch all day and watch TV, pretending to be normal.

Earlier this month, when protesters interrupted Gov. Phil Scott's State of the State address with chants of "Climate collapse means starvation in Vermont!" and "I'm afraid I'm going to die!" they were, in effect, demanding that he stop pretending to be normal.

A few hours before Scott's speech, a troupe of activists calling themselves the Red Rebels staged a glacially slow procession from the Unitarian Church of Montpelier to the Statehouse. They were mute and elaborately painted, like Elizabethan mimes or extras in a Stanley Kubrick movie, dressed entirely in scarlet. Their theatrical refusal of the pedestrian social contract — walk briskly, make friendly eye contact, try not to look creepy — was itself a demand: The world is on fire. Why are you in such a hurry to get to the office?

While Weston and the Red Rebels represent arguably extreme manifestations of climate panic, Vermonters in general are increasingly feeling its destabilizing effects, a seesaw of activism and nihilism. A survey by the Vermont Public Interest Research Group, released at the end of 2019, found that 61 percent of respondents feel "very worried" about climate change, compared to just 35 percent of respondents who took the same survey in 2016.

In those three intervening years, we elected a president who has, among other things, called climate change a hoax, undermined the role of scientific research in federal policy making and overturned Obama-era regulations on offshore drilling. More than 23 million acres of California — an area larger than the state of Maine — have burned. Three of the five costliest hurricanes in United States history struck in 2017, causing $265 billion in damage.

And that's just in this country. Within the last few months, fires in Australia have killed an estimated billion animals. Flooding in Jakarta has displaced almost half a million people and forced the Indonesian government to move its capital to the island of Borneo.

In light of these catastrophes, Oxford Dictionaries chose "climate emergency" as its phrase of 2019. Over the last year, use of the term has increased a hundredfold in the English language. Oxford's short-listed words of the year were also climate-centric: "climate action," "climate denial," "eco-anxiety," "extinction" and "flight shame."

On a recent morning at Pingala Café, a vegan eatery in Burlington, a twentysomething commented to her friend that on top of her "hangover shame," she was feeling "eco-shame" for drunkenly requesting an Uber home the night before.

"I know what you mean," her friend said solemnly.

Reasons to Panic

- Jeb Wallace-brodeur

- The Red Rebels

Since the mid-1800s, the advent of the industrial era, the average global temperature has risen by 1 degree Celsius. For decades, the scientific community has regarded an increase of 2 degrees Celsius as the precipice of the unthinkable. A glimpse over the edge: hundreds of millions of people exposed to deadly heat, floods, drought, and water and food shortages; 99 percent of coral reefs turned into underwater graveyards; up to 965,000 square miles of Arctic permafrost vulnerable to thaw, which could trigger the release of a gas 86 times more powerful than carbon as a greenhouse-effect multiplier.

These predictions aren't the doomsday prophesies of some fringe blogger; they come from the United Nations and NASA.

In 2016, the 187 signatory nations of the Paris Agreement (a number that, as of November 4, 2020, will no longer include the U.S., per President Donald Trump) agreed to "take action" to limit warming to 1.5 degrees. That increase, scientists now acknowledge, would still have dire consequences for much of the planet's human and nonhuman population. Seventy to 90 percent of the world's coral reefs would be wiped out, as opposed to 99 percent; a NASA study of 105,000 species of plants and animals found that 8 percent of plants, 6 percent of insects and 4 percent of vertebrates would suffer massive habitat loss.

Fires and floods, already occurring with nightmarish regularity in a world currently 1 degree Celsius warmer, would get even worse. Places like Miami and Bangladesh and the Marshall Islands might have a few more years to figure out how to get their citizens to higher ground.

In the wake of the Paris Agreement, 1.5 degrees of warming became our collective ecological Narnia — an alternate reality that seemed accessible via some combination of doing particular things and closing our eyes and wanting it badly enough. Not that the science was unclear: To achieve that goal, net global emissions would have to decrease. Instead, they've risen.

And while net emissions have begun to plateau and even decline in the U.S. and the European Union, those trends aren't significant enough to atone for the staggering amount of carbon we've already injected into the atmosphere over the past three decades. Nor are they enough to offset the footprint of the world's rapidly expanding economies — particularly China, which was responsible for more than a quarter of all global emissions in 2019.

The question — the same one that world leaders, scientists, policy wonks and technocrats have haggled over since before the invention of the DVD — is how to reduce emissions on a scale that would set us on the path to 1.5 degrees without crippling developing countries.

A recent simulation by Carbon Brief, a UK-based climate change science and policy research group, projected that net global emissions would have had to fall 3 percent every year, starting in 2000, to maintain any probability of curbing warming to 1.5 degrees within this century. Now, in 2020, emissions would need to decline by exponentially steeper increments each year, reaching net zero by 2040.

That vertiginous slope doesn't just represent a drop in fossil fuel emissions; it implies a total transformation of the structures and systems and human behaviors that produce them in the first place.

We're not there, not even close. In October 2018, the UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the historically sober-minded arbiter of climate data, released a report that decisively shifted the discourse: Even if every country met its Paris targets — a feat that would require cutting global emissions by 45 percent below 2010 levels, which are lower than current levels — the IPCC found that global temperatures are still on track to rise 3 degrees by 2100, barring immediate and drastic measures.

As one University of Oxford climate scientist and report contributor put it to the New York Times, "It's telling us we need to reverse emissions trends and turn the world economy on a dime."

And the 3-degree scenario — 1 degree warmer than the aforementioned hellscape — represents only the median portion of the probability spectrum. The IPCC projections, according to journalist David Wallace-Wells in his 2019 disaster panorama, The Uninhabitable Earth, run as high as 8 degrees. In that world, he writes, "the oceans would eventually swell 200 feet higher, flooding what are now two-thirds of the world's major cities; hardly any land on the planet would be capable of efficiently producing any of the food we now eat..." He continues with one apocalyptic example after another.

In sum, Vermont would become coastal.

State of Emergency

- Jeb Wallace-brodeur

- Extinction Rebellion activists at Gov. Phil Scott's State of the State address

In Vermont there is, as yet, no equivalent to a billion dead animals, which can help create the illusion that ecological disaster is something that happens elsewhere — that the state is too small and insignificant to affect or be affected by the worst impacts of climate change.

But climate change is an open system; Vermont's greenhouse gas emissions don't localize their long-term consequences. And even though Vermonters may be at considerably less risk than the approximately 600 million people who live within 30 feet of sea level, higher elevation in no way means imperviousness.

Already, in our present 1-degree-warmer reality, the amount of rainfall in the most intense storms in the Northeast has risen 71 percent since 1958. The Fourth National Climate Assessment, completed in 2018, found that the region is locked in to more than 2 degrees of warming by 2035, the greatest temperature increase in the contiguous U.S.; the intensity and frequency of precipitation events is only projected to get worse.

The Green Mountain snow season, on average eight days shorter now than it was three decades ago, will continue to shrink, affecting communities that depend on the winter recreation industry for jobs and revenue. More people will die of mosquito- and tick-borne illnesses, which are already on the rise: In 2017, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that Vermont now has the nation's highest per capita rate of Lyme disease. Perhaps the least of our worries is that the maple sugaring season could begin a month earlier by the end of this century; as the probability of major coastal flooding increases, so does the likelihood that Vermont will become a "receiving state," in the words of the 2014 Vermont Climate Assessment, for people displaced by hurricanes and higher sea level.

Vermont, of course, is no stranger to floods. According to data from the National Weather Service, average precipitation in Vermont has increased by almost six inches since 1960. In parallel, the number of federal disaster declarations in the state has been climbing. Since 2010, there have been 18, 13 of which have been issued since 2011. The most recent, last fall's Halloween storm, left more than 100,000 people without electricity, making it the fifth-largest outage event in the history of Green Mountain Power.

The worst of them all so far, Tropical Storm Irene, in August 2011, caused $733 million in damage. That figure represents only what the state and federal government spent on recovery efforts. The human cost — long-term physical and mental health effects, lost wages, the unseen economics of disaster — is much harder to calculate. One grim snapshot: A 2012 study by the U.S. Department of Commerce estimated that the relocation of state workers due to Irene deprived Washington County of $32.7 million in potential revenue.

Christine Carmichael, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Vermont's Gund Institute for Environment, has spent the past few years studying the psychological toll of Irene on Waterbury residents. In her research, she found that the overwhelming majority of people who experienced catastrophic flooding from the storm live in perpetual fear of losing everything again. Several people Carmichael interviewed said that they consistently wake up at night during heavy rainstorms to make sure the river isn't overflowing its banks.

To accommodate a reality in which deluges are no longer an anomaly but a persistent fact, the state's Hazard Mitigation Plan includes a voluntary buyout program for homeowners who live in flood-prone areas. The program, part of a post-Irene FEMA aid package, offers residents 75 percent of fair market value for their homes; under certain circumstances, municipalities will cover the difference. To date, 130 homeowners have taken a buyout. But there are some major obstacles, said Vermont Emergency Management director Erica Bornemann.

"A lot of people don't know that this program exists," she explained. "And the municipality has to apply on behalf of the homeowner. It can take a long time — a year to 18 months from the time the application is submitted — to get an approval. So it's not the silver bullet in terms of getting folks out of flood-vulnerable areas."

According to data from the state's Watershed Management Division, some 10,000 structures in Vermont's floodplains still await their turn.

Doomsday Web

- Luke Awtry

- Jane Dwinell

The internet has a kaleidoscopic effect on climate anxiety, refracting it into a million tessellations of fear and rage and spookery. The omniscience of Facebook and Google virtually guarantees that once you start clicking on articles about the wildfires ravaging Australia and the ever-shrinking window in which we might avert catastrophic warming, the nightmare stories will begin to find you. The instant proliferation of social media content, the simultaneity of the hellish and the trivial, only amplifies the absurdity.

In early January, Vermont-based writer and environmental activist Bill McKibben tweeted a photo of a beach encampment in Mallacoota, Australia, where nearly 4,000 people had sought refuge from the flames. An hour later, McKibben retweeted ExxonMobil Australia's New Year's wishes: "Stay safe and have fun this new year, from all of us at ExxonMobil Australia." The next item in my Twitter feed was an ad from the Wall Street Journal: "You're feeling depressed. What have you been eating?"

Memes, the tea leaves of the internet, have increasingly begun to reflect this existential distress, a self-mocking disgust at the squalor of our present condition. Recently, a photo of a humanoid-shaped shadow in an empty bedroom surfaced on Instagram, accompanied by this text: "in 2020 i'm shedding my physical vessel and becoming a void."

Among the more soul-obliterating corners of the doomsday web is a PDF titled "Deep Adaptation: A Map for Navigating Climate Tragedy." The author, Jem Bendell, is a professor of sustainability leadership at the University of Cumbria in Carlisle, UK; he published the paper on his own website in July 2018, after a peer-reviewed journal requested "major revisions" to the draft he submitted.

"Deep Adaptation" regards the climate crisis not as something to be understood purely through quantitative data — rising temperatures, melting Arctic ice — but as an all-encompassing juggernaut that requires a new philosophical framework. Bendell posits that most climate change research proceeds from the assumption that we can effectively manage the impacts of warming while maintaining the standard of living to which the affluent Western world has grown accustomed.

Based on his review of the latest climate science, Bendell concludes that that premise is both false and reckless — that humanity is, in fact, headed for "inevitable near-term social collapse due to climate change . . . with serious ramifications for the lives of readers." Now, he suggests, is the time to "step back, to consider 'what if' the analysis in these pages is true, to allow yourself to grieve, and to overcome enough of the typical fears we all have, to find meaning in new ways of being and acting."

A number of scientists and scholars have taken issue with Bendell's argumentative approach — namely, that he conflates "likely" collapse and "inevitable" collapse, without adequately substantiating either characterization. In spite of, or maybe because of, that epistemological thumb wrestling, "Deep Adaptation" has achieved a niche virality; in a February 2019 Vice story (titled "The Climate Change Paper So Depressing It's Sending People to Therapy"), Bendell claimed that it had been downloaded more than 110,000 times. (An illustration of its nicheness: "Someone in the alternative economics and Bitcoin crowd told me, 'Oh, everyone's talking about deep adaptation in London at all the dinner parties,'" he told Vice.)

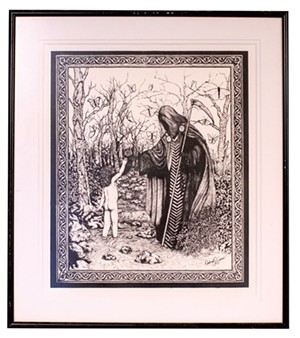

- Luke Awtry

- Tarot death card

One of the paper's downloaders was Jane Dwinell. A lifelong homesteader and semiretired Unitarian Universalist pastor, she currently lives in a net-zero house in Burlington's Old North End. She and her husband, Sky Yardley, grow most of their produce in their backyard. A framed 15-by-17-inch drawing of the death card from the Tarot deck hangs in their kitchen, a reminder of the inevitability of endings and the promise of regeneration. Dwinell, who used to work as a labor and delivery nurse at Gifford Medical Center in Randolph, is fond of the metaphor.

As we sat at her kitchen table one chilly November morning, warmed by a space heater that drew electricity from the solar panels on her roof, Dwinell told me that she had abandoned hope of reversing the trajectory of climate change long before she read Bendell's work.

"I mean, 20 years ago, even 10, I thought we could still turn it around," she said. In 2010, Dwinell published a book, Freedom Through Frugality [spend less, have more], a practical guide to releasing oneself from the manacles of consumerism and doing less harm to the planet. (A snippet: "If you feel you can't leave home without lipstick or nail polish, think about why that is.") But the book didn't sell very many copies, and carbon emissions kept rising. Dwinell got discouraged.

"Then, it started to feel like it was too late, with the feedback loops and everything," she said. "I'd read Bill McKibben's The End of Nature, and it seemed like climate change was accelerating."

This is a common refrain among the climatologically woke — the sensation that the world is deteriorating presently, rapidly, at double or triple speed, while everyone else's lives proceed at a normal pace.

When Dwinell first encountered "Deep Adaptation," in March 2019, she felt vindicated. Not long after, she became a moderator of the then-newly launched Facebook group Positive Deep Adaptation, named for its emphasis on productive, non-shaming discussion about how to physically and spiritually prepare for ecological collapse. Today, the group has nearly 9,000 members; Dwinell is the sole moderator on the East Coast of the U.S.

As a moderator, her main job is reviewing membership requests — the group receives, on average, 150 each week — and deep-sixing occasional trolls. The vast majority of members are concentrated in the U.S., the UK, Australia and Canada; seven, including Dwinell, live in Vermont, mostly in Chittenden County.

She divides the group into two categories: those for whom the prospect of climate-change-induced societal breakdown is "new news," and those, like her, who have been bracing themselves for decades. Most newcomers, Dwinell said, are looking for community, a place to express the all-consuming dread they can't talk about with the people in their off-line lives.

In the discussion thread, parents grapple with how to speak to their young children about what the world might look like by the time they enter adulthood. Recently, one mother from the UK wrote that she told her daughter, "We are going into a period that is going to be a lot like, you know, being in Europe and going into World War II. There may be a lot of chaos and confusion. There may be food shortages. Your dad and I are looking into buying some land to grow food — and I am doing my best to try to help in our community."

Others seek advice on what to do with their 401ks, fearing that retirement plans will offer no purchase in a warmer world. In late December and early January, members from Australia shared their terror and hopelessness — the sense that collapse was no longer a distant specter, but actual and unfolding over more than 23,000 square miles of the continent. One woman posted: "It's too late for growing or relearning. It's about survival now."

A disaster of that magnitude is unlikely to strike Vermont anytime soon. But Dwinell has steeled herself for whatever comes, whenever it comes. "I'm prepared," she said. "I know how to grow and find food. I know how to slaughter animals. I've built eight houses and renovated two. I know how to deliver a baby, and I know how to help somebody die."

2020 and Wellnessed to Death

- Caleb Kenna

- Lindsey Berk and Matthew Orchard

In 1816, known as the "Year Without a Summer" or "1800 and Froze to Death," a June blizzard dumped a foot and a half of snow on Cabot. Farmers who had already shorn their sheep tried to keep them warm by tying their fleeces back on, but whole flocks still died of exposure. In July and August, the temperature regularly dipped below freezing, killing the corn harvest for the year. The sun was dimmer, shrouded by a fog-like veil that wouldn't lift.

The culprit, though no one living then knew it, was the 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia, which launched enough sulfur and ash into the atmosphere to produce a sudden global winter that devastated crops throughout the northern hemisphere. Food shortages in New England prompted a mass westward migration. Vermont alone lost nearly 15,000 people, reversing seven generations of population growth.

Those who stayed behind noticed other strange things. In January 1817, steeples and fence posts began to glow. People's hair would spontaneously acquire a mysterious aura, as if lit from behind — a phenomenon called St. Elmo's Fire, the result of a strong electrical field generated by the volcanic eruption.

In an interview with Seven Days last fall, Vermont historian Howard Coffin noted that the religious fervor of the Second Great Awakening, which had begun a decade earlier, led many people to conclude that only the wrath of God could have been responsible for the surreal occurrences they were witnessing. Terrified, they prayed in droves. New England governors even prevailed upon their constituents to build more churches, hoping to regain divine favor.

Religion no longer wields the social and metaphysical authority that it possessed in the early 19th century. Today, we have the gospel of wellness and self-care, a $4.2 trillion industry predicated on the notion that the human vessel, particularly the female vessel, can and should be optimized. In its most blatantly capitalistic forms (SoulCycle, $8 cold-pressed juices), this relentless pursuit of optimization has taken on the zeal of spiritual pilgrimage, a culturally enforced ritual of self-flagellation and purification that feels entirely wrapped up in the fossil-fuel-powered narrative of economic productivity. Viewed in this context, goat yoga starts to look like an insanely depressing attempt to rectify our depraved ecological situation.

It's no coincidence that eco-anxiety tends to afflict the privileged — those for whom climate change is an internet rabbit hole rather than a life-upending reality. ("This is all about white people," said Dwinell, who is white herself.) At its extremity, one symptom is an obsessive preoccupation with the carbon impact of everything, analogous to the way someone with anorexia perseverates on calories.

As the enormity of the climate crisis dwarfs all of our psychological and political faculties, as things keep getting weirder and bleaker — what former Democratic presidential candidate Marianne Williamson called the "dark psychic force" of the Trump era — there seems to be a growing demand for new-age spirituality and its promises of transcendent self-soothing, unyoked from organized religion and capitalism. Astrology, in particular, has had a mainstream resurgence, especially among millennials. In a New Yorker story last October, an internet astrologer summed up the field's renewed appeal: "'In the Obama years, people liked astrology. In the Trump years, people need it.'"

Since climate panic has emerged as a specific ailment that requires specific therapeutic acknowledgment, a cottage industry of conferences, workshops and seminars has rapidly spawned to treat it. The American Psychological Association included half a dozen sessions on ecological grief at their 2019 annual meeting; in Burlington, Railyard Apothecary hosted an ecological grieving circle last November and has scheduled another on January 26. A climate panic-adjacent herbal workshop ("Inflammation, Anxiety and Climate Change") is planned for April.

In 2016, a year before the APA officially recognized "eco-anxiety" as "a chronic fear of environmental doom," a married duo founded the Good Grief Network — a free support group for people struggling with the weight of the climate crisis, modeled loosely on the Alcoholics Anonymous approach. (Step one of 10: "Accept the severity of the predicament.")

In January, activist Lindsey Berk launched the first Vermont chapter of the Good Grief Network. Berk and her partner, Matthew Orchard, are also members of Extinction Rebellion, which helped organize the protests during Gov. Scott's State of the State address earlier this month; Orchard was one of the chanters who interrupted Scott's speech. Recently, climate tragedy has struck close to home for them: Orchard, who grew up in Australia, has been watching his country burn on the news.

The couple recently bought a 140-year-old farmhouse a few blocks from downtown Brandon. Ideally, said Berk, she and Orchard would like to install solar panels on the roof and purchase an electric car, but for the time being, they can't afford to do both. The two of them are so panicked about the state of the planet that they're not sure if they want to have children — a sentiment that many people in their activism circles share. When the topic came up at a recent Extinction Rebellion gathering, Berk told me, several women started crying; to them, bringing new life into the world no longer seems morally justifiable.

In Berk's view, Good Grief provides a necessary outlet for these complicated feelings. "We live in an emotionally constipated society," she said. "We've lost community, we've lost our bodies, we've lost nature. This is a safe space for people to move through their ecological grief without letting it paralyze them."

Berk, 36, is trained in vinyasa yoga and restorative yoga for trauma. Last fall, she led a women's retreat in Joshua Tree National Park in California; she has since decided she will no longer organize events that require her to get on a plane. The retreat agenda included a sound bath in the Integratron, a wooden-domed cupola in the desert. Its architect, the prominent UFO apologist George Van Tassel, believed the structure was capable of facilitating both cellular rejuvenation and time travel.

Berk plans to incorporate a few different modalities into the 10-week Good Grief curriculum — "ecstatic dance, soundbaths" — to help people get out of their heads and live more fully in the present, even if that present is an increasingly uncomfortable place.

The evening after the Statehouse protests, Berk held the first Good Grief session at a Pilates studio in Brandon. Of the 13 people in the circle of yoga mats, only three, including Orchard, were men.

After acknowledging that we were on the unceded lands of the Abenaki — a standard disclaimer within Vermont's climate-justice movement — Berk asked each person what they hoped to gain from the workshop. Several people mentioned "resilience." Others spoke about "adaptation" and "community." One woman said she wanted to "find her feelings again."

Yet another woman explained that ecological grief has made her day-to-day life feel like "playing house," an elaborate and pointless game. "Seeing birds used to give me a sense of joy," she said. "But now it's like, 'How much longer will I be able to see them?'"

Eventually, Bianca Zanella, poet-in-residence at Phoenix Books in Rutland, led the group in a writing exercise, aided by tea lights, essential oils and crystals. ("Does anyone need a rundown of which crystals do what?" Zanella asked before passing them around.) After a warm-up meditation, several people shared the images that had appeared to them — a tree with a missing branch, a dry riverbed, bees carrying their dead from a hive.

At the end of the class, Zanella invited everyone to stay in touch via email. "Also, I've been told that I'm a really good hugger," she said. "So if anyone needs a hug, feel free to come and get one." At least one person — the woman who said that her life felt like playing house — took Zanella up on the offer. I almost did, too.

Green New Deal or No Deal

- Luke Awtry

- Clarissa Sprague

For the better part of the last decade, Vermont's war against the climate crisis has played out primarily on the rhetorical front. In spite of its environmental activism-industrial complex and smorgasbord of nonprofits with regenerative-sounding names — Community Resilience Organizations, Vital Communities, Efficiency Vermont — the state's greenhouse gas emissions have risen 16 percent since 1990.

After President Trump announced in 2017 that he planned to withdraw the U.S. from the Paris Agreement, Gov. Scott issued a statement affirming Vermont's commitment to "reducing the region's carbon emissions." While utility companies have made some progress toward transitioning to renewable energy sources, the state still hasn't achieved a single one of its emissions reduction goals.

Johanna Miller, the energy and climate program director of the Vermont Natural Resources Council, feels this dissonance acutely. In 2017, Scott appointed her, along with 20 others, to his newly formed Vermont Climate Action Commission. A year later, the commission submitted 53 proposals to Scott; he has yet to act upon any of them.

"The governor has said the right things, but, substantively, there's virtually nothing there," Miller said. "But most Vermonters aren't following the minutiae of policy progress, so when you hear him saying the right things, you assume that he's also doing the right things."

This false equivalence of language and action is partly what enables us to live in a seemingly consequence-free present, a world in which reusable shopping bags and compostable forks have become proxy signifiers of virtue. At the start of the 2020 legislative session, Vermont's Climate Solutions Caucus outlined several policies to help reduce emissions, including urging the state to join the Transportation and Climate Initiative — a cooperative agreement among 12 Northeast and Mid-Atlantic states, plus Washington, D.C., that would generate revenue for green transportation programs by raising taxes on fossil fuel companies.

Early projections have estimated that the proposal could drive up the price of fuel as much as 17 cents a gallon, an increase that Scott has indicated he wouldn't support. The governor has, however, indicated that he would support more electric vehicle incentives for consumers. (He is particularly excited about the electric Ford Mustang, which, as he noted in his State of the State address, can do zero to 60 in 3.3 seconds, with zero emissions.)

Meanwhile, the Sunrise Movement, a national youth coalition with more than 10,000 members, has been ramping up its efforts to swing elections in favor of environmentally progressive candidates. Sunrise launched in 2017 to advocate for politicians who support renewable energy; in the 2018 midterms, half of the 20 candidates whom Sunrise endorsed won office. Among them were Democratic Representatives Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York, Debra Haaland of New Mexico, Rashida Tlaib of Michigan and Ilhan Omar of Minnesota.

Over the past year, Sunrise has pivoted to fighting for the Green New Deal, a resolution introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives last February by Ocasio-Cortez and Democratic Sen. Ed Markey of Massachusetts.

The concept of a Green New Deal predates the House resolution; the writer Thomas Friedman was among the first to popularize it in a 2007 column for the New York Times. In its current iteration, the Green New Deal proposes a transition away from fossil fuels on a macro level.

Among the systemic reform goals it outlines are zero-emissions public transportation, universal health care, guaranteed wages and ending the oppression of "frontline and vulnerable communities" — including "indigenous peoples, communities of color, migrant communities, deindustrialized communities, depopulated rural communities, the poor, low-income workers, women, the elderly, the unhoused, people with disabilities, and youth."

The Green New Deal isn't legally binding, nor does it contain any specific legislation. But from Sunrise's point of view, the resolution has come to represent a political litmus test: If you don't sponsor it, you don't grasp the extent of the climate crisis. In the House, 67 Democrats — including Vermont Rep. Peter Welch — have signed on as cosponsors. Thirteen Senate Democrats, plus independent Bernie Sanders, whom Sunrise endorsed for the 2020 presidential race, have also sponsored the resolution.

Vermont's senior senator, Democrat Patrick Leahy, has publicly voiced support for some of the principles of the Green New Deal but has stopped short of signing it. In an interview with WCAX-TV shortly after the resolution was introduced in the House, Leahy acknowledged its contents vis-à-vis his own legacy: "I've already written a lot of things that are in there — in housing, in conservation, in environmental standards, in alternative forms of energy," he said.

Leahy continued: "It's nice to say, 'We're all for this,' but then do the hard work to get there. I've been doing the hard work for decades, and so much of what's in the green plan reflects things I've gotten for Vermont and gotten for the country and will continue to, as long as I'm on the Appropriations Committee."

UVM junior Clarissa Sprague leads the 40-some members of the Burlington chapter of Sunrise. Sprague stayed on campus over Thanksgiving break to organize a protest calling out Sen. Leahy's inaction on the Green New Deal, which took place on a Friday afternoon in early December, a coordinated day of climate strikes for Sunrise chapters across the country. Wielding hand-painted banners ("LEAHY, WHAT SIDE ARE YOU ON?"), Sprague and about 15 student activists crammed themselves into the elevator of Courthouse Plaza on Main Street in Burlington and rode it up to Leahy's state office on the fourth floor.

Sprague knew that Leahy wouldn't be there, so the plan was to talk to his chief of staff, John Tracy, and whoever else answered the door. (When the group convened an hour or so beforehand to strategize, Sprague advised them: "They're going to take whatever you say and twist it to serve their purposes. Stay on message.")

There was barely enough room for everyone in the waiting area of Leahy's office, where Tracy and Leahy's environmental policy adviser, Tom Berry, met the protesters. As members of the group introduced themselves and shared why they wanted the senator to support the Green New Deal, Tracy and Berry waited patiently, wearing the impenetrably forbearing expressions of parents considering whether to grant an allowance raise.

Thirteen-year-old Veronica Lindstrom, an eighth grader at Lyman C. Hunt Middle School, spoke first: "It's terrifying to think about what my future might look like, and having an idea like the Green New Deal gives me a little bit more hope that I'll have a future to look forward to."

Tracy then explained that the Green New Deal was nonbinding, and that while Leahy thought it was a good platform, he was more interested in sponsoring legislation that would "actually make a difference." At one point, Tracy said that the senator would be cosponsoring the 100% Clean Economy Act, which would direct organizations under the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to create a plan to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

Chris Harnell, a UVM junior, interjected: "That's not soon enough."

Tracy looked fatigued. "I'm just telling you the legislation he's signed on. They can always work on dates."

"Well," said Harnell, "that makes me feel like he doesn't understand the scope of the crisis, because I know that it has to be by 2030, and the UN knows it has to be by 2030. So why doesn't Sen. Leahy know that it has to be by 2030?"

Tracy sighed. "I appreciate your perspective, and trust me when I tell you that Sen. Leahy has been focusing on these issues forever."

Afterward, Sunrise held a candlelight vigil in front of the "Democracy" sculpture outside of Leahy's office building. In spite of the snow, nearly 100 people turned out, including Tracy, Berry and 73-year-old Anne Damrosch. In tears, Damrosch told me that she came because she was terrified for her grandchildren.

"This isn't fair," she said. "I'll be gone before it gets too bad."

Two days later, VTDigger.org posted an article about the vigil, and several commenters mocked the student activists. "I see lots of polyester jackets in those photos," one person wrote. "Lead by example, kids." Another posted: "You think decades of declining test scores does not matter? This here is what it translates into."

In response, someone lamented: "Condemning protestors for wearing polyester or burning candles is akin to arguing that because they breathe out CO2, they must either be ignorant of or not care about global warming ... It's hard to read this junk and not despair."

Sprague had been planning to spend her spring semester abroad in New Zealand. But over the past few months, she'd begun to feel uneasy about abandoning her role at Sunrise and getting on an international flight. A few weeks after the vigil, she made up her mind: She would go to New Zealand for three months, not six, then return to Burlington to spend the second half of the semester leading Sunrise and working on other climate actions in Vermont.

"Deep down, I know we won't make it out of this," Sprague said. "But the next election determines whether we do it with grace."

Rebels and Reality

- Chelsea Edgar

- Sunrise Movement vigil

Extinction Rebellion, whose official Facebook page has approximately 364,000 likes, consists of hundreds of autonomous chapters in dozens of countries and at least 30 states; its deliberately nonhierarchical structure makes precise membership statistics elusive.

The group has a penchant for tactics with a theater-of-the-absurd vibe. Last October, for instance, Extinction Rebellion protesters in New York City hauled an 18-foot fishing boat into the middle of Times Square. Dozens of people handcuffed and superglued themselves to the boat, a visual allegory of the plight of refugees escaping deteriorating social conditions due to climate disaster.

A week and a half later, Extinction Rebellion organized a three-day encampment in front of the Vermont Statehouse to protest the legislature's inaction on climate change. They weren't there to make any specific policy demands; philosophically, the group is more interested in large public displays. To that end, the encampment involved several days of speeches, at least one dance party and a draft horse, which belonged to Hartland farmer Stephen Leslie.

Dan Batten, the group's Vermont coordinator, said that some people had hoped to raise the profile of their demonstration by getting arrested — sleeping on the Statehouse lawn is technically illegal — but the Montpelier police accommodated their presence without so much as issuing a fine.

Batten, 52, who works as a technical writer for an insurance company, has neatly cropped hair and the general aura of someone who has never seen the inside of a jail cell. In fact, Extinction Rebellion is his first foray into the world of civil disobedience.

Batten and his family are, in a sense, climate migrants: They moved to Vermont last year from Richmond, Va., where they had a small farm with chickens and rabbits. Batten said they had considered installing solar panels on their property and going off the grid, but southern Virginia's increasingly hot summers, combined with the bleak ecological prognosis, compelled them to go north instead.

"We figured that people are going to be on the move in the decades to come, so we wanted to move to a state that had already done some work as far as renewables are concerned," Batten said. "Our daughter is 13, and we thought it would be really helpful for her, 30 or 40 years from now, to be established here already." The family now lives in Bristol Village Cohousing, a solar-powered community of 14 households.

Batten first learned about Extinction Rebellion in the fall of 2018, shortly after the IPCC released its sobering report. Around that time, members of the group in London, where the movement began, staged a human blockade of the city's major tunnels and bridges, effectively forcing a shutdown of the daily commute.

The demonstration, intended to physically enact the disruptive impacts of climate change, prompted a smattering of press coverage in the U.S., including a New York Times story headlined: "Commuters Drag Climate Activists From London Trains."

Batten was impressed. When he discovered that Vermont had a fledgling Extinction Rebellion chapter, with a 12-person mailing list and no designated leader, he volunteered to take charge. Since then, five regional chapters have sprung up across the state, and the general mailing list now includes more than 600 people.

Extinction Rebellion's steady growth in Vermont is at least partly attributable to what members refer to as "the talk." That's an hour-plus-long PowerPoint — equivalent to a fifth-grade sex-ed lecture in terms of its life-altering potential — that lays out a précis of our collective ecological fate. By Batten's estimate, he's given the presentation, titled "Heading for Extinction and What to Do About It," at least 15 times.

On a Wednesday evening in early November, the prospect of extinction was enough to summon nearly 50 people to the basement of Montpelier's Kellogg-Hubbard Library, where Batten was delivering an iteration of "the talk." That night, Batten was struggling to get the PowerPoint to display on the projector. As more and more people filed in, widening the circle of chairs until almost every available inch had been annexed, there was a sense of thwarted medieval expectation, as though we had come to witness a hanging, but the noose wasn't tight enough.

A woman with shoulder-length gray hair took a long, noisy drag on a juice box.

"I have a friend who's a member of the Colorado astrology association," she offered. The projector sighed briefly to life, then conked out again. "She told me that Mercury is in retrograde."

Someone suggested that it might be time for Extinction Rebellion to invest in a new projector. Someone else corrected: a new used projector. The consensus was that we were witnessing but the first sneeze in industrial civilization's long, consumptive decline. Eventually, Batten gave up on the projector and decided to show the slides from his laptop.

"This is not a fun talk," he announced grimly. "I hope you didn't come to be entertained."

For the next 90 minutes, Batten waded through Extinction Rebellion's synopsis of the latest climate science. The only viable course of action, the presentation concluded, is mass mobilization to demand radical and immediate change, on par with the civil-rights movement and Mahatma Gandhi's nonviolent resistance to British imperial rule.

A few weeks later, a woman who had attended the talk in Montpelier went to an Extinction Rebellion meeting in Burlington. She told me that she probably wouldn't go back to the Montpelier chapter, because she noticed that Batten had been drinking out of a single-use plastic water bottle during his presentation. She then confessed — glancing around the room furtively, as though someone might be eavesdropping — that she drives a gas-powered SUV.

Correction, January 22, 2020: An earlier version of this story misstated the disclaimer from the climate grief workshop.

Comments (12)

Showing 1-12 of 12

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.