- Courtesy Of Vermont Glove/adam Plotsky

- Mark McKerley cuts material at Vermont Glove's facility in Randolph

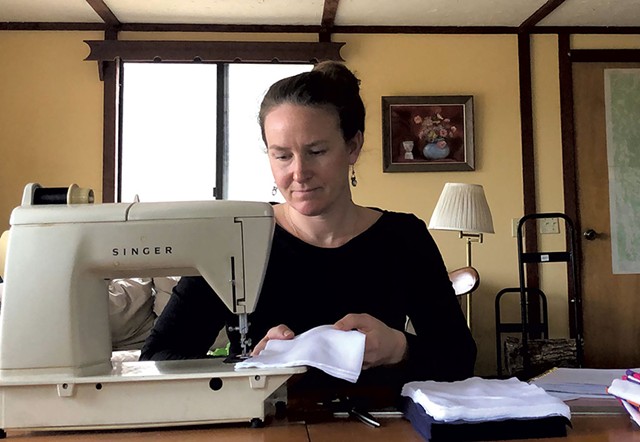

Each evening, Calley Hastings throws a stack of up to 50 cotton face masks into her Subaru Crosstrek and drives down a muddy road to a rendezvous point not far from her Brookfield home. There, she meets the owner of a local manufacturing company and trades the masks for more materials, most of which she will distribute to about 10 other home sewers around her neighborhood. Saving some fabric for herself, she heads home to work on the next day's batch.

Hastings, who also runs her own goat's milk caramel business, Fat Toad Farm, adopted this routine more than a week ago. Quickly shaking off any rust that may have gathered in the dozen years since she fired up her grandmother's old Singer Touch and Sew machine, Hastings said she can now "bust out" her assignment with little effort. The work provides her with a much-needed sense of purpose to combat the feeling of helplessness engendered by the coronavirus crisis, she told Seven Days.

"As long as the machine doesn't break too many times," she joked.

Hastings and her neighbors are foot soldiers in a growing army of home sewers that Vermont Glove has enlisted to produce the protective gear. Eight full-time employees are working staggered shifts at the leather goods manufacturer's facility in Randolph to cut the materials, which are then delivered to the home sewers to be assembled. The company, which has made gloves for more than 100 years, is now selling the face masks both wholesale and on its website for $6 each.

- Courtesy Of Calley Hastings

- Calley Hastings sewing a mask at home

The cotton masks cannot substitute for medical-grade N95 masks that are most effective in filtering out the coronavirus. But health experts say any face protection is better than none, and some medical professionals have started wearing cotton masks over their N95s to prolong the N95's life. Others who work in the public sphere have taken to wearing homemade fabrics so that the coveted medical-grade ones are freed up for hospitals.

The shift has allowed Sam Hooper, Vermont Glove's president, to aid the relief efforts and avoid laying off any employees. He told Seven Days that he's finishing up a last batch of glove orders this week before transitioning to the masks full time. He expected to ship out roughly 4,000 masks this week to buyers — including the Vermont State Police, the Vermont Department of Corrections, private companies and individuals. Home sewers will be paid $1 for every mask they produce once the company starts receiving payments, Hooper added, though some have already offered to volunteer their time.

"We're doing it just to be made whole," Hooper said last week. "We're not really making a buck on this."

Vermont Glove is among at least a dozen small manufacturing companies that have pivoted in recent weeks to produce critically needed medical supplies amid a nationwide shortage. Last week, Burlington maker space Generator announced it had used a 3D printer and open source designs to create a face shield for frontline medical workers that it hopes to mass-produce once its prototype is approved. Skida, a Queen City headwear and accessories company, has started making gowns for health care workers. A few distilleries have started brewing hand sanitizer.

Related Generator Maker Space Prototyping Face Shields for Hospitals

The grassroots mobilization underscores the innovative spirit that has come to define Vermont's manufacturing community and reflects the same communal response to crisis that surfaced in the wake of Tropical Storm Irene nearly a decade ago. But while Vermont manufacturers may take on an even bigger role in the weeks to come, some companies eager to help have been unsure exactly how to do so, causing some frustration.

"They want to solve the problem," said Bob Zider, director and CEO of the Vermont Manufacturing Extension Center. "Manufacturers are generally like that — they want to make something happen. So immediately there's a frustration if they can't find an outlet or a place where they can begin to put their back to the plow."

In the three weeks since Vermont confirmed its first coronavirus case, Green Mountain manufacturers have received little official guidance on how to make products that are actually helpful to medical professionals. Many medical supplies must meet specific standards to be used in hospital settings, and even then, products usually undergo tests before they can be deployed.

As Vermont officials work closely with hospitals to try to ensure that they don't run out of supplies, state government would seem like the most logical clearinghouse for information on what needs to be made, and how. But state agencies have been slow to tell manufactures exactly what they need.

Several business and trade organizations that spoke to Seven Days recalled fielding hundreds of questions from anxious manufacturers over the last few weeks. But they didn't know how to respond when companies asked about retooling to produce supplies, said Lisa Ventriss, president of the Vermont Business Roundtable, a nonprofit that serves more than 100 CEOs of some of Vermont's biggest employers.

"Interest on the part of people to help has been there for weeks," Ventriss said. "We simply didn't know yet what form that help should take."

The Lake Champlain Regional Chamber of Commerce has been equally unsure what to tell the dozen or so area manufacturers with a desire to help, according to executive vice president Catherine Davis. She said the organization has told companies to "sit tight" as it works to figure out the next steps with the state. She acknowledged that can be a difficult message to hear for companies that have seen "their entire worlds shift in a two-week period."

"Stress, as we know, breeds impatience," she said. "They so want to be a part of the solution. We just need to have some patience to figure it out."

- Courtesy Of Vermont Glove/adam Plotsky

- Vermont Glove president Sam Hooper showing off some of his newly produced face masks

The state has made some progress recently. Officials working with outside groups last week identified a list of medical supply needs, with N95 masks, ventilators and hand sanitizer topping the chart, according to Chris Carrigan, vice president of business development at the Vermont Chamber of Commerce. That organization and several others have also collaborated with the state on surveys that will gauge which manufacturers have the capacity to donate those specific items or start producing them on their own. And the administration of Gov. Phil Scott last week designated a single agency, the Department of Buildings and General Services, to coordinate these efforts moving forward, which should make it easier to share information.

The business groups concede that the state would be closer to harnessing the power of the manufacturing community had these steps come sooner. But none spoke critically of the state's response. Instead, they praised government officials for swiftly adapting to unprecedented challenges.

"We learn little by little," Zider said. "It's kind of like walking into a tunnel with a flashlight. You can only see so far ahead. You got to take another step, and you can see a little further."

The leaders' only criticism was aimed at the federal government for what they say has been an inadequate response to the outbreak.

"Would we have been better off if the president had listened to the information he got in December, so in January and February we could have prepared for this? Absolutely," said Ventriss, of the business roundtable.

Indeed, President Donald Trump has come under fire for failing to take sufficient action during the crisis, most recently over his resistance to enact the Defense Production Act. The 60-year-old law gives the federal government power to direct industries to produce crucial items during times of need. Trump eventually invoked it last Friday afternoon, calling on General Motors to manufacture ventilators — but only after governors around the country, including Scott, urged him to do so. Two days later, the president accused states of requesting more equipment than they need.

Vermont, meantime, has scrambled to amass supplies for an expected surge in coronavirus patients. Agency of Human Services Secretary Mike Smith said last week that the state needs to at least double its capacity of hospital beds, personal protective equipment and ventilators. Public Safety Commissioner Michael Schirling was less willing to cite a specific number of items the state may need. He said his response to such questions has consistently been: "As many as we can get ahold of."

"We're buying them as fast as possible," the commissioner said at a press conference last week.

Schirling said the state's request for personal protective equipment from the federal government stockpile falls somewhere in the "millions" of items. The Trump administration has offered some help. Six truckloads of equipment delivered this weekend, for example, exceeded the state's warehouse capacity, prompting the Vermont National Guard to build a temporary holding area, the commissioner said.

Still, state officials have warned against complacency; Vermont likely faces significant competition for further supplies from other states, some of which have received only a fraction of their requests so far. At Monday's press conference, Scott said Vermont is not relying on the federal government.

"We're pulling every lever we possibly can and finding a lot on our own," Scott said. Schirling added that Vermont manufacturers would likely play a role in those efforts. He told Seven Days on Tuesday that the University of Vermont Medical Center is working on a prototype ventilator that could be produced in the Green Mountain State.

Until then, smaller companies like Vermont Glove say they plan to keep doing what they can to help out. Hooper is working to find the materials needed to produce masks that are more protective. He also anticipated that more companies would join the relief efforts. He said that's because Vermont companies share two key attributes, both of which will be required to get through the pandemic: "a lot of grit and a lot of neighborly care."

"It's just a part of the way of life here," he said.

Comments (2)

Showing 1-2 of 2

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.