- Kym Balthazar

Moments after taking office as Vermont's 82nd governor, Republican Phil Scott pledged to a Statehouse chamber filled with Democratic and Progressive legislators that he would "rise above the politics of division and partisanship."

Scott acknowledged that he and the assembled lawmakers wouldn't always agree. "But," he continued in the January 2017 inaugural address, "we must always treat others the way we want to be treated."

By all accounts, he meant it. During his 16 years as a state senator and lieutenant governor, the excavation company owner from Berlin had built a reputation in the Statehouse for kindness, integrity and civility. A lifelong Republican, he'd won four statewide elections in liberal Vermont by espousing a centrist philosophy and a commitment to cooperation.

So it came as a surprise to Scott's former colleagues when, over the next 18 months, he presided over two of the most acrimonious legislative sessions in recent history. He vetoed a record 13 bills — including three of just four budget vetoes in state history — and brought Vermont to the brink of an unprecedented state government shutdown.

To be sure, Scott has occasionally bucked his party to work with the legislature's Democratic majority, most notably when he signed a series of new gun restrictions into law. And he has distanced himself from the toxic rhetoric of his party's standard-bearer, President Donald Trump.

But even as Scott has preached a high-minded gospel, his staff has failed to follow suit. By turns antagonistic and aloof, they have alienated Scott's closest friends in the legislature and sapped him of his greatest asset: goodwill.

"There's the Phil that everybody saw as senator and lieutenant governor. And what we see as governor is really, really different," said House Speaker Mitzi Johnson (D-South Hero). "Something in there changed."

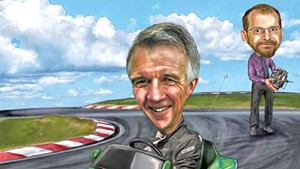

That "something," according to many of Scott's allies and adversaries, is the omnipresence of the governor's combative chief of staff, Jason Gibbs. The 42-year-old operative, who cut his teeth as Republican governor Jim Douglas' sharp-tongued spokesperson, has consolidated power in Scott's Montpelier office — and, some say, over the governor himself.

Gibbs' influence, actual or imagined, is such that he is widely referred to behind his back as "Gov. Gibbs."

Over the last month, Seven Days spoke with three dozen legislators, cabinet officials, gubernatorial aides and outside advisers about Scott's leadership style — and that of his chief of staff. (Several of those who work in the administration or maintain close ties to it refused to be named for fear of professional retribution.) While most argued that the governor maintains control, some of his closest compatriots complained that Gibbs' aggressive approach has exasperated legislators and undermined Scott's agenda.

"He's a fighter, you know? That's a great quality about him, and it's also a bad quality," one cabinet member said of Gibbs. "Politics is a human game, and if most of the humans are mad at you, it's hard to play the game."

A second cabinet member put it this way: "Phil's a genuinely nice guy, but there seems to be a bit of a disconnect when it comes to staff." Asked whether the governor was well-served by Gibbs, the official said, "No comment."

Even Sen. Dick Mazza (D-Grand Isle), a Scott loyalist who chooses his words carefully, questioned Gibbs' approach. "There's room for improvement," Mazza said. "Jason, from time to time, can ruffle feathers."

Gibbs casts a long shadow over state government. According to career employees of three executive branch departments and agencies, he and Scott's other top aides regularly ignore or overrule nonpartisan staff to push a conservative agenda, particularly concerning the environment, education and taxes.

Kirby Keeton, a policy analyst and former interim general counsel for the Department of Taxes, has found the situation so alarming that he felt obligated to speak out publicly. In previous administrations, the self-described whistle-blower said, gubernatorial aides might ask for data to inform a policy decision. But in this one, "They make a political decision and ask for data to support it."

Such intrusions into day-to-day governance have been "demoralizing," according to a high-level manager in another department. "I can live with [staff] decisions being overturned," the civil servant said. "But those decisions should be overturned for reasons that are in the interest of Vermonters, not in the interest of an administration."

Scott, who prides himself on running a technocratic administration with an empowered cabinet, said in an interview last month that he was surprised to hear such complaints and pledged to address them with his secretaries and commissioners. "If their team doesn't feel as though they have a voice, then they need to reach out and do a better job," he said of his cabinet members.

But the governor excused his political aides for occasionally failing to "rise above" the fray. "I think my team is very loyal and very defensive when it comes to me," he explained, characterizing himself as "a sitting duck" in the face of Democratic attacks. Scott is up for reelection in November to a second two-year term and is being challenged by former Vermont Electric Coop CEO Christine Hallquist, a Democrat.

Asked whether he'd heard the moniker "Gov. Gibbs" before, Scott went silent and appeared surprised. "No," he said with a forced chuckle.

"It couldn't be further from the truth," he said, calling his chief of staff loyal, engaging and inquisitive. "We don't agree on everything. We have our own debates. But in the end, I win, you know, because I'm governor — and that's the way it is."

A Study in Contrasts

- File: Jeb Wallace-brodeur

- Jason Gibbs talking with Gov. Phil Scott

Scott brought to the governor's office few of the attributes that defined his immediate predecessors.

Unlike Democrat Peter Shumlin, a born salesman who brimmed with self-confidence, Scott is an introvert who would rather listen than speak. And unlike Douglas, who spent virtually his entire career in state government, Scott came to politics and policy late in life.

The 60-year-old Barre native studied technical education at the University of Vermont and went on to run motorcycle-repair, restaurant, nightclub and excavation companies. "Because he was in the construction business, he thinks, What are the plans? Show me the blueprint," Gibbs said.

Though Scott spent a decade in the legislature, he mostly served on the Senate Transportation Committee and the Senate Institutions Committee, both of which are known more for doling out money than setting policy.

"I think it's healthy to have someone who it's all new to," said Scott's secretary of administration, Susanne Young, who previously worked for Douglas. "You really get a fresh look with someone who has not really lived and breathed it."

Johnson, the House speaker, has a less charitable take: "I don't know if he can sit down and explain how education funding works," she said.

"Phil is not comfortable in his clothes," echoed a Democratic legislator who has been friends with Scott for years. "He's not comfortable in detailed policy analysis."

When Scott took office in 2016, he hired a chief of staff who compensated — or perhaps overcompensated — for what he lacked. In Gibbs, he found a fierce political operative who could flesh out and give voice to a shared philosophy of fiscal conservatism and social libertarianism.

Though their politics are similar, their style is not. "He's a bit of a warrior," Scott said, "and he likes the debate."

That's been the case since Gibbs, the Brandon-born son of a tool-and-die machinist and a bank teller and bookkeeper, joined the Otter Valley Union High School debate team in the early 1990s.

"He was pretty much the same then as he is now," said Sen. Peg Flory (R-Rutland), whose youngest son was on Gibbs' team. "Very sure of himself. Very bright. Doesn't always pick up well on people cues."

The University of Massachusetts graduate joined Douglas' first run for governor in 2002 and worked his way up from campaign chauffeur to gubernatorial spokesperson to commissioner of the Department of Forests, Parks and Recreation. After losing a bid for secretary of state in 2010, Gibbs took time off from politics — other than a stint on the local school board — and worked in marketing and communications. He lives in Waterbury with his wife, Amy, and their daughter.

Gibbs returned to the game during the 2016 election, serving as an unpaid adviser to Scott's gubernatorial campaign and then on his transition team.

As Scott's chief of staff, Gibbs oversees an 18-person office that handles the governor's policy, media, legal and constituent-service needs. He's a member of the cabinet and serves as a liaison to Scott's secretaries and commissioners. But the most demanding part of the 70-hour-a-week job is staffing the governor himself — as gatekeeper, briefer, troubleshooter and minder.

"He doesn't drink enough water," Gibbs said of his boss. "So I sometimes worry about whether he's hydrated enough."

No duty is too big or small for a chief of staff. In his office last month on the fifth floor of Montpelier's Pavilion Building, Gibbs showed off a floor plan he'd drawn on a massive whiteboard to help him reallocate office space in the governor's suite. For 23 minutes, Gibbs delivered an uninterrupted, jargon-laced monologue focused largely on his plans to reinvent state government and reimagine the budgeting process.

"I mean, I'm kinda dorkin' out here," he concluded with a self-satisfied grin, finally allowing a reporter to ask a question.

While the role of chief varies depending on the needs of a governor, it almost always entails playing bad cop to the boss' good cop. "It's a job of no, not yes," said Liz Miller, who served as the second of Shumlin's three chiefs of staff.

Unlike many of his predecessors, who stayed behind the scenes, Gibbs prefers to take center stage. According to some who have attended meetings with the two, the chief does the talking — one top legislator described it as "mansplaining" — while the governor does the listening. And when the administration faces criticism, Gibbs is frequently the one who fires back — over the phone, on Twitter or in the press.

"He's aggressive, and he carries out the plays that the governor calls, and I sometimes think that that energy is mistaken for something else," said Brittney Wilson, who managed Gibbs' secretary of state campaign and now runs Scott's reelection bid. "Jason means well. He really does."

Scott, who has raced stock cars most of his adult life, compares Gibbs to his longtime crew chief at Barre's Thunder Road SpeedBowl.

"Usually drivers are the ones who are very intense, high-strung, and the role of the crew chief and spotter is to calm the driver down," the governor explained. "Well, it was just the opposite with my crew chief ... I mean, sometimes he would say over the radio, 'You gotta go get that guy! You've gotta go retaliate!'"

For Scott, the role reversal worked. "We had a lot of success," he said. "I mean, we won a lot of races."

Coffee Talk

Lieutenant governors in Vermont have few formal responsibilities other than to preside over the Senate and fill in for the governor in his absence. But during Scott's six years in the post, he used it to cultivate personal relationships with lawmakers of every political stripe.

When a senator went missing in the Statehouse, chances were that he or she could be found yukking it up with Scott and Mazza over free coffee in the lieutenant governor's first-floor corner office.

In April 2015, when Scott's counterparts in Connecticut and Rhode Island pitched a regional partnership to improve Vermont's troubled health insurance exchange, the lieutenant governor invited two top Democrats on a road trip. Sens. Jane Kitchel (D-Caledonia) and Tim Ashe (D/P-Chittenden) piled into Scott's black pickup truck and drove to Providence to vet the idea.

Ashe, now the Senate president pro tempore, said he'd take such a trip again "in a heartbeat," but he's not waiting by the side of the road. "It's been a different experience dealing with him as governor," the pro tem said.

These days, according to Flory, the governor seems "sheltered" from his Senate friends. "I miss the casualness," the Rutland senator said.

It's not just about bruised feelings. Legislators say the distance has impeded collaboration and compromise, and they complain that Scott's staffers are scarce around the Statehouse.

"Our contact with the administration is really pretty limited," said Kitchel, who chairs the Senate Appropriations Committee. She noted that few of Scott's aides have experience in state policy and said they were often absent during key committee debates.

"The disengagement of his team is probably the primary challenge," Ashe said.

In one memorable episode early in Scott's tenure, Gibbs issued what he called an "informal directive" urging newly hired administration officials to avoid after-hours fraternizing with lawmakers and lobbyists. Hitting the bars in Montpelier, he explained to the Vermont Press Bureau, "can be counterproductive to the priority of governing."

A year and a half later, as lawmakers were preparing for a special session to resolve a budget veto, Scott's legislative lobbyist, Kendal Smith, sent a memo asking policy officials in each agency and department to steer clear of the Statehouse. "If [legislators] see you there they will be tempted to continue conversations on other issues outside of education financing ... diluting their focus," she wrote.

Senate Majority Leader Becca Balint (D-Windham) thinks it's a mistake to limit interaction between the two branches.

"We're too small a state to not be talking and interacting with each other," she said. "We were framed as an enemy."

Fish & Wildlife Commissioner Louis Porter, a former legislative lobbyist for Shumlin, is skeptical that relations are any worse than usual. "I think that some of the criticisms by legislators and others about the Scott administration are very similar to the ones I heard about in the Shumlin administration," he said.

The only difference, according to special assistant to the governor Dustin Degree, is that Democrats no longer control both the legislature and the governor's office, so disagreements are more likely to spill into public view.

"The Shumlin administration and the legislature had these same exact tiffs," said Degree, a former state senator. "They were just done in the quiet of a committee room."

Gibbs, for one, appears to loathe the legislature. During the interview in his office, he gestured dismissively at the Statehouse whenever he mentioned its occupants. He suggested, wrongly, that legislative leaders had put Seven Days up to this story.

At first, he denied any discord — and then he blamed it on the other side. The governor, he argued, is struggling mightily to "reset the political architecture" and leave behind tribalism and partisanship, but Democratic and Progressive legislators see that as a threat to their power and would rather "weaken" Scott than work with him.

"My boss wants to ... leave the political environment better than we found it, and that bothers some of them because they look at it and think, Well, we don't want people to think well of moderate Republicans," Gibbs said. "That wouldn't be good politics."

Gibbs and other fifth-floor staffers regularly cite a closed-door Senate strategy session in February 2018 during which Democrats and Progressives sought to counter Scott's messaging success. As Seven Days reported at the time, Sen. Michael Sirotkin (D-Chittenden) urged his colleagues to send Scott a slew of politically popular bills in order to "get a bunch of vetoes."

"If he vetoes everything, he's gonna have some 'splaining to do," said Sen. Ann Cummings (D-Washington).

Though the senators sounded desperate and divided, Gibbs characterized the event as evidence of a grand conspiracy. In his eyes, it explained away Scott's record-setting veto spree and justified Gibbs' own rhetoric.

"There's a point in time where you have to stand up against your political adversaries," the chief of staff argued. "There's an unfortunate reality where sometimes you have to push back on them and fight fire with fire."

'The Authentic Phil'

- File: Jeb Wallace-brodeur

- Gov. Phil Scott

The trouble with Gibbs' narrative is that it ignores the first 13 months of the Scott administration and the vetoes that preceded the Senate's infamous strategy session.

Many trace the animosity back to the governor's first days in office, when in his January 2017 budget address he proposed freezing school district budgets and forcing teachers to pay a higher percentage of their health insurance premiums. The plan, which surprised lawmakers, would have required them to immediately delay Town Meeting Day school budget votes and meddle in local spending decisions.

It was a nonstarter.

Scott dropped the matter until April, when just weeks before adjournment he suddenly made a new demand: to shift school employee health insurance negotiations from the local to the state level, a change he promised would save up to $26 million. Though legislators had heeded his call to hold spending in line, Scott vowed to veto the state budget if it did not include his last-minute proposal.

The legislature resisted, and the governor carried through on his threat, making him the second governor in Vermont history to veto a budget.

"I think we may have surprised them with our resolve," said Young, the administration secretary.

According to one Scott ally, it was a mistake to provoke the legislature with such a last-minute demand. "You don't pull this out in April," the veteran Republican said. "It was just an opportunity lost to build trust and show that the governor is a man of his word."

At times, the administration and legislature have managed to find common ground. They quickly agreed to a $35 million bond to help build hundreds of new homes to address Vermont's housing shortage. And when Trump launched a crackdown on illegal immigration, they rallied around legislation limiting state cooperation with the feds.

Most notably, after a February 2018 school shooting in Florida and a foiled plot in Fair Haven, the two camps collaborated to enact Vermont's first significant restrictions on gun ownership. While Scott typically allows Gibbs to drive the policy-making process — particularly when it comes to education finance — his aides said the governor took charge of the gun legislation.

"That was the one thing where you saw the authentic Phil," Johnson said. "That was the one conversation at our weekly meeting where I would turn to him and ask a question and he would answer it, not his staff."

'Another Day in the Office'

A year after the first budget standoff, the administration found itself in a familiar place: making a last-minute demand to hold the line on education property taxes, this time by using $34 million in surplus revenue to buy down tax rates.

Shap Smith, a former Democratic House speaker, took to Twitter to eviscerate the plan, calling it "a fiscal joke" and arguing that it would result in higher taxes the following year. "It's the wrong answer," he wrote.

"Um...None of that is true," Gibbs responded in a tweet. "Would be happy to debate it on WDEV or VPR or anywhere if you're so inclined."

Two days later, the men were sitting side by side on a Statehouse couch wearing headset microphones as WDEV-FM host Dave Gram moderated a testy debate. Lawmakers, lobbyists and reporters clustered around them, blocking a hallway to the Statehouse cafeteria.

It was an unusual spectacle in Vermont politics, an arena in which public officials typically make their arguments directly to constituents, not through spokespeople or surrogates. To some, it seemed that Gibbs was upstaging the governor in order to satisfy his own ego.

"I mean, I wouldn't do it," said the first of the two cabinet members who would not be named. "I'm not the governor. I'm not the principal. I'm the curtains."

Neale Lunderville, who worked with Gibbs in the Douglas administration, argued that it can be helpful for others to amplify the governor's message while allowing him to stay above the fray.

"Every administration has employed that tactic in one way or another," Lunderville said. "Sometimes you want the staff to be out in front on something."

But sometimes the staff go too far. A month later — after Scott vetoed his second state budget and just before he vetoed his third — his campaign sent a mass email to supporters referring to his rivals as "extremist Democrats and Progressive party leaders."

The email, which quoted Sirotkin's and Cummings' comments at the Senate strategy session, alleged that legislative leaders had "manufactured" a government shutdown threat "because they are so deeply committed to raising your property tax rates and/or trying to make the Governor look bad."

Wilson, the campaign manager, said she wrote the email — and later got a talking-to from the governor. "To be honest with you, I didn't think that 'extremist' was worse than 'extreme,' but apparently people thought that was too far," she said. (Gibbs claims he neither approved nor remembered the email.)

One casualty of the education finance fights, in addition to civility, has been expertise. According to an Agency of Education official, fifth-floor staffers have ignored and undermined its experts. "We have been pushed aside. We have not been listened to. We have not been asked questions," said the official, adding that the agency was uninvolved with Scott's major education policy proposals.

Keeton, the tax policy analyst, said his department had also been bypassed in that debate.

"The ideas the administration brought these last two sessions for education financing did not originate from the tax department. These were fifth-floor proposals," Keeton said. "If you actually had experts at AOE and Tax working on this stuff, you wouldn't have these half-baked proposals."

Said one former Scott appointee, "There was an unwillingness to really understand the full scope of an issue before putting a proposal forward."

Commissioner of Taxes Kaj Samsom disputed the notion that his department took a back seat to Scott's aides, saying that policy development is "always a two-way street" between career staff and political appointees. As for Keeton, Samsom said, "He was not in a position to have much insight into how those policies were developed."

Whatever their origin, the legislature's nonpartisan Joint Fiscal Office also found fault with the administration's work. When JFO analysts scrubbed the numbers on one Scott plan in May, it found what it called "major technical errors," to the tune of $100 million to $160 million.

Gibbs did not take kindly to the critique. "The JFO analysis reflects a desire on the part of legislative leadership to undermine the arguments the governor is making in his plan," he told VTDigger.org at the time.

Ashe demanded that Scott denounce Gibbs' comments, which the Senate president compared to Trump's attacks on the U.S. Congressional Budget Office. Scott apologized at a press conference, but a week later Gibbs did it again, accusing the JFO of intimidating administration officials and hiding their math.

"It suggested either that Jason was being really ill-disciplined or that the governor and his team had signed off on it again, which would've been out of character," Ashe said.

The Senate responded with a unanimous resolution condemning Gibbs' remarks and praising the JFO's neutrality. Even Scott's legislative allies supported the resolution.

The episode prompted Sen. Chris Pearson (P/D-Chittenden) to call for Gibbs' ouster over Twitter. "I think it's time for the governor to reflect on his staffing choices and decide to let Jason Gibbs go," Pearson explained recently. "I think he's a destructive voice on the fifth floor."

Asked last month about the controversy, Scott said, "That was one opportunity where he could've done better." But Gibbs himself still isn't sorry. During the interview in his Pavilion office, he retrieved a stack of printed news stories and Twitter exchanges in an attempt to show that his comments had been taken out of context and that he had been "baited" into engaging in the first place.

"I regret that I kind of fell into that trap," he said.

How did it feel to be the subject of a Senate resolution? "Not to be glib, but it didn't feel like anything," he said. "It just felt like another day in the office."

Owning It

Gibbs said he recognizes that he's viewed as "a mean-spirited, aggressive political animal." But, he counters, "People who know me — who really know me — actually understand that, while I can be energetic, I am well-intentioned."

As for the "Gov. Gibbs" moniker? "I think it's profoundly unfair to the governor, and it's embarrassing to me," the chief of staff said.

Others on the fifth floor back him up. "That's just not at all grounded in reality or in truth," said Young, the administration secretary. "Gov. Scott is very much in charge."

In contrast to the caricature, Gibbs argued, Scott "can be a little bit of a micromanager." He insists on reading and approving every scheduling request and responds to the most minute details in his cabinet members' weekly reports.

One recent obsession, according to Gibbs, has been the upcoming commissioning of a U.S. Navy submarine to be named after the Green Mountain State. Scott wants to know how many Vermont veterans he can bring to the Connecticut event, where they will stay and how much it will cost. "This is the construction contractor in him," Gibbs said. "'I'm responsible for this job. I've taken it on. I need to know every detail.'"

Scott may keep quiet in meetings, his supporters say, but that shouldn't be mistaken for disengagement. Rather, they argue, he's taking in the information he needs to come to a decision — and letting his staff do the grilling.

"He's quiet and he's reserved, and I think sometimes people read that in a certain way, but they're wrong," said one Scott aide. "He's not easy to read."

Though some Democrats pin the governor's problems on Gibbs, others argue that doing so lets Scott off the hook. "The governor hires his staff, and his staff are reflective of his priorities and his values," said Kitchel, the Senate Appropriations chair. "If he has a staff and he is deciding that their advice is sound, then he owns it and it's his."

Whether their advice is sound isn't quite clear. Though Scott may have won the messaging war in the budget fights, the legislature ultimately prevailed on the substance. In June, after vetoing the budget twice and bringing the state to the edge of a government shutdown, the governor blinked and let the legislature's spending package become law without his signature.

It's also unclear what voters think of those decisions. A poll conducted by Morning Consult in the spring showed Scott's support slipping among Republicans after he signed Vermont's new gun laws, but the governor went on to defeat a conservative challenger in the August primary. There has been little public polling since, so there's no way to know how he's faring against Hallquist, the Democratic gubernatorial nominee.

While some have speculated that Scott will shake up the fifth-floor staff if he wins reelection, the governor himself said he expects no major changes and has "no reservations" about Gibbs' performance.

"I think he's served me well," Scott said.

That may be, suggested one Republican ally, because the governor doesn't know there's a problem. "He is so protected in his bubble that people aren't sure what's getting to Phil," the ally said. "How would he know? Everything is filtered through Jason."

Disclosure: Tim Ashe is the domestic partner of Seven Days publisher and coeditor Paula Routly. Find our conflict-of-interest policy here: sevendaysvt.com/disclosure.

Comments (9)

Showing 1-9 of 9

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.