- Suzanne Podhaizer

- Brio Coffeeworks

Coffee math used to be a lot simpler: Is it cheaper to buy the grounds in the blue can or the red and yellow can? How many sugar packets will it take to render a massive cuppa gas-station joe palatable? If I guzzle that whole Styrofoam cup of swill, how many hours will it take me to fall asleep?

As with many consumables, appreciation for coffee has grown over recent decades. Some treat it as not just a caffeine-delivery system but a prized beverage. And, accordingly, the calculations have gotten trickier. Today, consumers can dive as deeply into coffee lingo and logistics as they'd like, learning the differences among beans grown in various microclimates of a region of Costa Rica or exploring the relationship between roast level and sweetness in the cup.

A few years back, it seemed comedic to listen to people order fussy espresso drinks: "Can I have a venti half-caf latte with soy milk and caramel? On ice." Take a hipster to a coffee bar today, and she might ask for a pour-over of bright, citrus-y Ethiopian Sidamo, roasted to just before second crack.

A few years ago, that request would have been gibberish to all but the most fervent coffee drinkers. To many, it still is. Perhaps because it's treated as fuel, and some hesitate to shell out for a better cup, coffee doesn't yet enjoy the same exalted status as scotch or Cabernet. But it's clearly a beverage on the rise. And, while our coffee industry may get less national ink than our craft breweries, we can make one shocking statement with certainty: Vermont businesses play a part in nearly every cup sold in the United States.

- Michael Tonn

This is not true of gallons of milk or growlers of craft beer, or even of jugs of maple syrup. The Green Mountains' climate doesn't permit the growing of coffee beans, yet Vermont has become a coffee superpower.

Why? A little history: In 1981, a former rolling-paper salesman named Robert Stiller decided to snap up a coffee shop in Waitsfield, located near his Sugarbush ski condo. He parlayed that venture into Green Mountain Coffee Roasters — the now-beleaguered behemoth that was renamed Keurig Green Mountain in 2014 and sold to an investor group this March.

KGM has weathered financial troubles over the years: Stiller has lost, regained and re-lost his billionaire status and was finally forced out as chairman of his company's board. Environmentalists target the business for selling single-serving K-Cup pods — nine billion of them in 2014 alone — that are neither compostable nor easily recyclable. (You can recycle portions of the K-Cup after pulling it apart into its component pieces, but who actually does that?)

Yet KGM employs more than 6,000 people worldwide and, according to Fortune, controls 20 percent of the retail coffee market in the U.S. And it has demonstrated a dedication to social responsibility: It engages in water-restoration projects, donates to nonprofits that strengthen coffee-growing communities and encourages staff members to do volunteer work.

In Vermont, one of KGM's most significant impacts, aside from providing jobs, is training the next generation of coffee entrepreneurs — people who left the company but stayed in the state to start their own businesses. It's the coffee parallel of the New England Culinary Institute, which has seeded the restaurant industry with graduates, and hence new eateries, around the state.

KGM alumni form the backbone of Vermont's coffee industry, joined by coffee lovers who moved to the area for its touted quality of life. Some are coffee testers and theorists, some are activists working to spread the wealth, and some roast the beans or serve them, but all are committed to a higher appreciation for the quality of each cup.

Behind the Scenes: Analysis and Education

- Jeb Wallace-brodeur

- Coffee Lab International staff Shannon Cheney, Debby Pakbaz, Mané Alves, Maxwell Duquette and Josh Parker cupping coffee

Dan Cox, who was the first full-time staff member at Green Mountain Coffee Roasters, is one of the coffee industry's movers and shakers, both locally and nationally. He rose through the ranks to become GMCR's vice president, and has served as national cochair of the Specialty Coffee Association of America. After he and Stiller parted ways in 1992, Cox founded a trifecta of Burlington-based businesses: Coffee Enterprises, Coffee Analysts and Coffee Ed.

Slated to move in the near future, those businesses currently occupy impressive headquarters in Burlington's Lakeside neighborhood. A floor-to-ceiling window in Cox's office affords a stunning view of Lake Champlain. Framed newspaper articles about the company hang in the conference room, and pre-Columbian artworks decorate the walls. When it's tasting time, a ceremonial gong summons employees.

At Coffee Analysts, Cox's associates use sophisticated equipment such as refractometers and vacuum ovens, along with their own highly trained palates, to put coffee beans and packaging through their paces. Vice president Spencer Turer has worked in the coffee industry for more than 20 years.

"Out of the top 10 coffee companies, we test for nine of them," Cox says. Those include national brands such as Folgers, Kraft and KGM. They do quality testing for Dunkin' Donuts, too.

- Jeb Wallace-brodeur

- Debbie Pakbaz

While Coffee Analysts is about the sensory evaluation and analysis of coffee products, Coffee Enterprises guides professionals through the intricacies of working in the coffee industry. It offers assistance with business planning and marketing, coffee purchasing, and mergers and acquisitions, as well as other matters of law. Cox has even written a book, Handling Hot Coffee: Preventing Spills, Burns, and Lawsuits, to help save beverage businesses from legal action. Through the third arm of the business, Coffee Ed, the team provides customized training for those who work in the industry.

One of Cox's points of pride is that his outfit — which includes the "largest independent testing facility in North America" — is not a coffee roaster, nor is it involved with the production of coffee for sale. "We're completely independent," he notes. "We're not competing with any of our clients."

Mané Alves takes a different approach. A former (brief) employee of Cox's, he founded his own company, Coffee Lab International, in 1995. Like Cox's suite of businesses, CLI offers product analysis, testing and education. Unlike Coffee Enterprises, Alves and his staff also roast and sell coffee under the name Vermont Artisan Coffee & Tea Co.

Alves travels five months out of the year, sourcing beans from farmers who have exceptional practices and produce the highest-quality coffee. In Waterbury, those beans may be kept single origin — for instance, a Guatemalan coffee that comes from organic-certified suppliers with plantations on the shores of Lake Atitlán — or combined into blends with consistent flavor profiles. Many baristas, including Elizabeth Manriquez, owner of Espresso Bueno in Barre, swear by Vermont Artisan's espresso blend.

CLI's environment is relaxed and casual. Its staffers include lab director Shannon Cheney, a sensory analyst who is a former employee of KGM and a 20-year industry veteran, and Maxwell Duquette, who fell into the coffee business during college. Duquette found a mentor in Alves and now works in sales and marketing. Both are bursting with coffee enthusiasm and eager to talk about their work.

A tour of the facility includes a stop in the roasting room, which has nine roasters ranging in size from petite to gigantic, and a visit to the tiny kitchen, where a Kegerator hums. What's inside? Cold brew.

- Suzanne Podhaizer

- Cold brew at Coffee Lab International

In the cup — or, in this case, a tulip glass typically used for fancy beer — the cold brew is refreshing and complex and has a rich, smooth mouthfeel akin to that of a fine stout. The product has been in development for nearly two years; Vermont Artisan plans to release it at the Vermont Brewers Festival this July.

Next on the tour is the tasting room, where the coffee analysis and testing occurs. Cups of beans sit out on tables, and shiny water boilers are lined up on the counter. Cupping, the highly structured procedure by which coffee is slurped and scored, is a precise and serious business.

In the coffee industry, those who have passed an arduous series of tests administered by the Coffee Quality Institute are dubbed "Q graders," licensed to analyze and grade Arabica coffee. Q graders — who develop skills similar to those of sommeliers — determine whether beans can be graded as specialty coffee, a distinction reserved for those that have few defects. Bags of beans that smell and taste delicious and arrive sans broken or underripe beans, mold and stray husks, translate to better returns for the grower.

Cox was the second American ever to earn the Q grader distinction. Four members of the Coffee Analysts staff are also Q graders. Four members of Alves' tasting team likewise bear that title, and Alves himself is one of just 34 instructors worldwide who can train and test new Q graders. He's taught more classes than all but one of them.

Q grader classes require intense attention to detail and culminate in a rigorous test. They are also pricey: $1,650 for a six-day stint. When Duquette took the class, which he passed, 12 of the other 15 attendees failed.

CLI's other courses include a five-day session on roasting and cupping, and two-day instruction on becoming an excellent barista.

Perhaps it's a positive commentary on the state of the industry that, like Coffee Enterprises, CLI has outgrown its current digs. This fall, it will relocate to a new facility on Route 100 in Waterbury Center. There, CLI will have a dedicated classroom for its School of Coffee, as well as a new café where customers can sample and learn.

Holly Alves, Mané's wife and CLI's president (and a former employee of KGM), says the café will provide an outlet for the tiny lots of boutique coffee that Alves comes across in his travels. Too small and too costly per pound for regular production runs, these lots are perfect for roasting on-site and selling by the cup to interested drinkers.

Nonprofits and Economic Development

- Suzanne Podhaizer

- Coffee plant in Puerto Rico

Like that of many food products, coffee production has a dark side. The Coffea plant genus grows in equatorial regions between the tropics of Cancer and Capricorn, so much of the world's coffee is sourced from impoverished nations, some of them embroiled in conflict. Each coffee-growing nation has its own laws governing exportation and its own legal and ethical standards for labor.

Because coffee is a commodity product — the second most traded good in the world after oil — much of it is sold for a minuscule price per pound. Furthermore, coffee growing is seasonal and subject to the vagaries of precipitation, temperature and plant diseases, so it rarely yields sufficient profit to create stable businesses and communities.

That's where Food 4 Farmers comes in. The mission of the Hinesburg-based nonprofit is to help bring food security to coffee-growing communities. Says codirector Janice Nadworny, "The price of coffee doesn't support farmers adequately. They're not earning enough income to feed their families, send their kids to school, have electricity." Coffee's commodity status, combined with increasingly challenging climatic conditions that can lead to more disease, will keep that from changing any time soon.

Nadworny compares the plight of coffee farmers to that of Vermont dairy farmers producing commodity milk. Some have been able to stabilize their livelihoods using value-added product lines or diversification.

Coffee farmers have similar options. But, as Nadworny points out, coffee-growing regions lack many resources available to businesses in the United States, and farmers there endure tribulations that American farmers don't. "In many communities, roads might be washed out, there could be guerrillas, or [growers] might have to pay off the paramilitary so they don't wreck their farm," Nadworny says.

Starting with "community diagnostics" that help identify regional strengths and challenges, F4F helps coffee growers come up with strategies. For instance, farmers might bring in a secondary industry such as beekeeping. "There's a huge demand for delicious coffee-flower honey," Nadworny says. "People want to buy it, and the income is significant right away."

F4F also helps farmers who have extra land but no resources to purchase seeds and plant new crops. For instance, it's working with a coffee-growing cooperative in Nicaragua, consisting of 750 families, to start the area's first farmers market.

"There's only one supermarket, and it's owned by Walmart, and it carries all processed and expensive food," Nadworny explains. The new market, which she compares to the Intervale Food Hub in Burlington, will give families a fresh alternative. "It looks like [Vermont] 20 years ago," she says. "It's the very same integrated process of strengthening a local food system."

Overall, says Nadworny, "We're helping transfer this knowledge and power to these farming communities so they have choices."

Many of F4F's board members and advisers work in the coffee industry, or study it. They include founder Rick Peyser (former director of social advocacy and coffee community outreach for KGM), who works at Lutheran World Relief; Mané Alves; Brio Coffeeworks co-owner and president Magda Van Dusen; and Ernesto Méndez, an assistant professor at the University of Vermont, who analyzes "interactions between agriculture, livelihoods and biodiversity conservation."

Cox helped found and serves on the board of another Vermont nonprofit, Grounds for Health. Its mission is to "reduce cervical cancer among women in developing countries" by partnering with coffee cooperatives and health organizations in Africa and Latin America. To date, GFH has screened more than 61,000 women and helped treat 4,177.

Artisan Coffee and Indie Roasters

- Suzanne Podhaizer

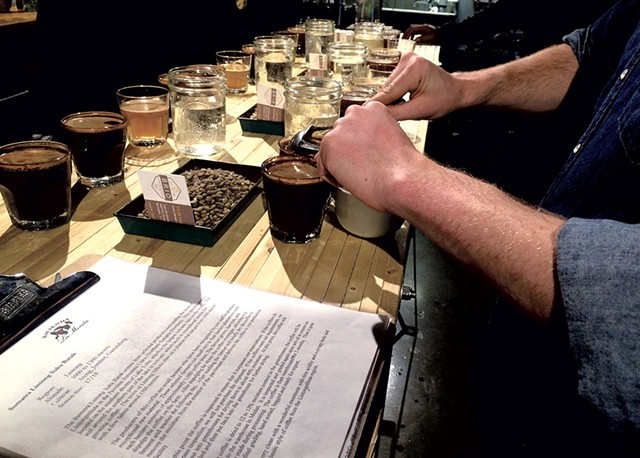

- Public coffee cupping at Brio Coffeeworks

When food professionals talk about the American coffee industry, they often refer to three "waves." During the first wave, which began in the 1800s, mass production, vacuum packaging and global shipping made coffee widely available to consumers.

The "second wave," which is sometimes associated with the rise of Starbucks, refers to consumers' embrace of espresso and coffee drinks and their increasing curiosity about coffee growing and roasting.

While Vermont has plenty of first- and second-wave coffee businesses, small-batch roasters such as Vermont Artisan and Brio in Burlington belong to the third wave. The term was coined by San Francisco roastmaster Trish Rothgeb in 2002 and encompasses the interest many now take in the finer details of coffee production and brewing, as well as social responsibility.

Third-wave coffee roasters characteristically source their beans from individual farms and cooperatives rather than whole regions, attend to tiny gradations in roast temperature, and find creative ways to engage with consumers. Each Friday at noon, for example, Brio offers a public cupping at its Pine Street roastery. The session allows participants to acquire some in-depth coffee knowledge and play at being sensory analysts for an hour.

Although Vermont now has dozens of small roasters, Turer, Cox and staffers at CLI believe there's room for more. Rather than competing with one another for the same customers, roasters should be trying to convert commodity coffee drinkers into specialty coffee drinkers, local experts suggest.

In tough economic times such as these, why should people spend more on beans and brews? Some would say the future of the industry depends on it. Like dairy farmers, coffee producers thrive when their products are more highly valued. And, as with other specialty foods, the extra dollars typically flow toward those who take better care of soil, employees and products.

"The specialty coffee industry pays very close attention to the medical conditions and social conditions" in coffee-growing communities, says Turer.

Cox adds, "Until the specialty guys came along, I didn't see the bigger guys getting involved [in social missions]. If we don't help [coffee farmers], we won't have anything to sell."

Green commodity coffee is sold cheaply — it's currently trading at about $1.22 per pound — but specialty coffee is prized. Esmeralda Geisha, one of the most expensive beans, is grown in one small valley on a single Panamanian coffee plantation. In 2013, it fetched $350.25 per pound at auction. Although the Geisha is the most dramatic outlier, it illustrates the point: Farmers do better when they grow specialty coffee.

So do other members of the supply chain. According to Cox, each coffee bean is handled about 18 times — from tree to burlap sack to customs — before being purchased by its final consumer, and everybody who handles it needs to get paid: exporters, importers and roasters alike. Specialty coffee, because it has fewer defects and is handled more carefully in production, generally tastes better, too.

Granted, that's never guaranteed. After all the effort that goes into growing beans, moving them around the globe, storing them and roasting them, the final product can be rendered unpleasant by a thoughtless barista or some dude in his pajamas with bedhead.

- Suzanne Podhaizer

- Camille Berlioz making a pour-over at Maglianero

That's where cafés come in. As artisan roasting has increased, so have the options at coffee shops. Well-trained baristas will be able to identify the best brewing method for your tastes — whether French press or Chemex — and prepare your drink with care. At Burlington's Maglianero, for instance, which uses beans from North Carolina's Counter Culture Coffee, baristas favor the AeroPress and pour-over methodologies for the consistent and flavorful cups they produce.

A quick primer on methods: The pour- over resembles what happens in a drip coffee maker, except you're pouring the water by hand over the grounds. The coffee seeps through a filter, leaving the cup free of sediment. The Chemex, invented in 1941, is a glass coffee maker using a manual pour-over system. The AeroPress features a plunger like a French press but has key differences such as a finer-gauge filter.

Preparation options may be complicated, but engaging with excellent coffee doesn't have to be. Scout & Co., which has three locations in the Burlington area, buys from Vivid Coffee, which roasts beans on location at Scout's Winooski shop, and other local roasters. Baristas, including co-owner Tom Green, are happy to tell you about the flavor notes in your cuppa, if you're interested. Or you can just get yours with smoked maple syrup and a torched marshmallow and sit in the sunny window with a coffee in one hand and a Miss Weinerz artisan doughnut in the other.

- Suzanne Podhaizer

- Cappucino at Scout & Co.

Yes, the fetishization of specialty food products such as coffee can be annoying — especially when self-styled connoisseurs start foodsplaining. But those who care deeply about the aesthetic qualities of their coffee often also care about coffee farmers and choose beans that are grown and harvested sustainably. That care and attention translate to a more stable and resilient livelihood for producers.

Roasters and cafés that are willing to charge a little more for their products — and consumers who are willing to pay it — believe in something more than a caffeine high. Their conviction can transform communities, both in coffee-growing countries and here in Vermont, as the state's thriving coffee industry demonstrates.

So, when your friend asks for a cold-brewed cup of locally roasted coffee from the Kibuye valley of Rwanda, excited about its notes of chocolate and peach, instead of dismissing the hipster-speak, you may want to taste what that's all about.

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.