- Luke Awtry

- Sue Schein

Sue Schein has fond memories of visiting childhood friends on Caroline Street in Burlington. In the 1950s, the South End neighborhood was home to young families whose patriarchs toiled at the nearby lakeside factories. The area was affordable, unpretentious. Everybody knew everybody. And to young Sue, it felt like home.

Decades later, Schein bought her first house on that very street, a modest bungalow built in 1923 with a small apartment upstairs. The wooden floors are close to a century old, and, with few exceptions, the fixtures are original to the house. The area's friendly vibe hasn't changed either. At age 74, Schein relies on neighbors to help with yard work and drive her to appointments — favors she repays with homegrown vegetables and matzo ball soup made from scratch. Schein, a retired radio broadcaster and college instructor, calls the arrangement her "assisted living plan." She aims to age at home for as long as possible.

The city's recent property reassessment may upend that plan. Schein's duplex more than doubled in value, from $249,800 to $605,300. The property tax bill that came last month was equally shocking, increasing from $7,457 to $12,998. Even after her state rebate — which is based on her roughly $40,000 annual income from pensions and rent — Schein will owe an additional $448 a month. She never worried about taxes until now.

"My stomach is filled with acid; my back is cramped up in spasms. I'm virtually sleepless, and I'm crying a lot," Schein said. "I'm willing to pay a share that's equitable, but mine is nutsy-cuckoo out of scale."

Burlington's housing costs were already high, but the city's first reassessment in 16 years has only worsened matters for the large majority of homeowners. High demand has driven up home prices — a phenomenon exacerbated by the flood of out-of-state buyers during the pandemic. Commercial property values have grown modestly overall, but many took big dips as downtown went dark due to pandemic shutdowns. Homeowners are being squeezed to make up the difference.

Many residents were stunned when they received their home's new valuations in mid-April, but they still didn't expect the tax increases — thousands of dollars in many cases — contained in the bills that came in July. Landlords are passing their higher costs on to tenants. Renters and homeowners alike fear they're being priced out, and some are questioning why the city would conduct a reassessment during a pandemic that had already toppled any semblance of normalcy.

"The timing could have been much better," said Wanda Hines, a lifelong resident of Burlington's Old North End, whose tax bill increased by $1,518 this year. "Even though I understand that it was long overdue, they could have been a little more sensitive to the overall economic instability ... that we were already up against."

City leaders say they didn't have much choice. The state Department of Taxes mandated the reappraisal three years ago, after Burlington's assessed values dropped to below 80 percent of fair market value. This number, called the common level of appraisal, determines whether a town is paying enough to the state education fund. Burlington's post-reassessment common level of appraisal is close to 100 percent, suggesting that home values are on par with the market.

"The goal of the adjustment is to reach greater equity," Mayor Miro Weinberger said. "On the whole, I'm confident this worked."

The city contracted with Texas company Tyler Technologies for the general reassessment and used a separate Massachusetts-based company, SOA, for commercial valuations. The entire process cost $1.1 million.

The reassessment was "revenue neutral," meaning both the municipal and education tax rates were adjusted downward to account for higher property values. If a property owner's valuation rose more than 40 percent — the average for all taxable property citywide — their tax bill went up, too.

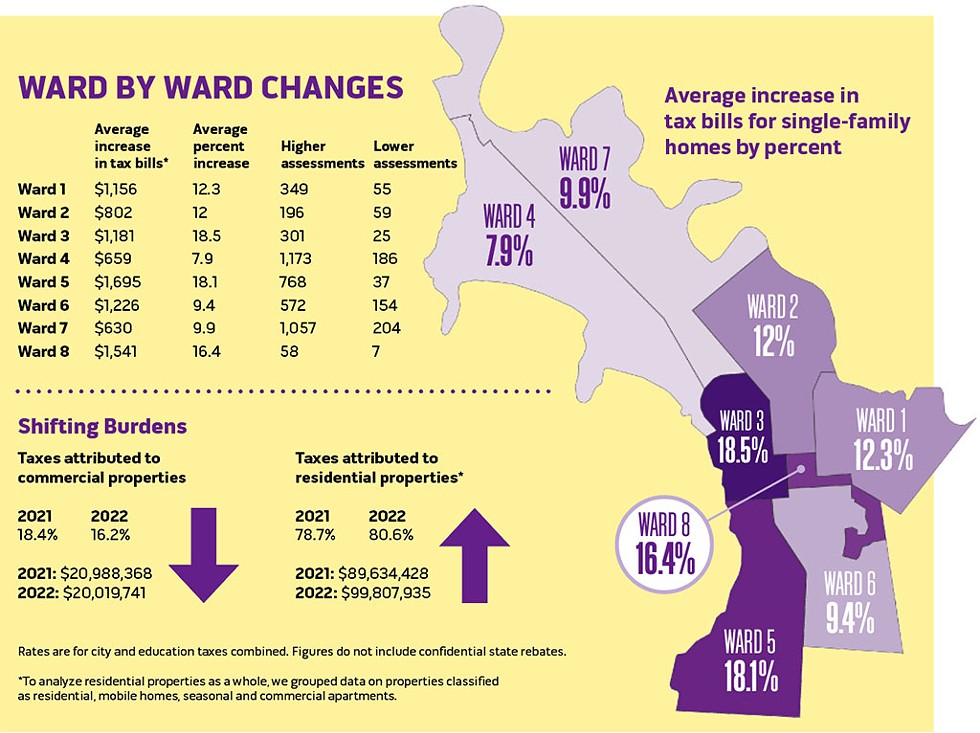

That's the case for 86 percent of single-family homes, the most prevalent property type in Burlington, though the actual increases varied. Ward 5, in the city's South End, has boomed with breweries and other amenities since the last reassessment — resulting in an average $1,695 tax increase, or 18.1 percent year over year. By contrast, taxes on single-family homes in Ward 4, the New North End, went up by 7.9 percent, or $659 on average.

Yet even as residential tax bills increased overall, those for commercial properties dropped. On the whole, residential property owners will pay the city roughly $10 million more in taxes this year, but commercial properties will collectively contribute nearly $1 million less.

Unlike residential valuations, which are calculated using data from recent sales, commercial values are largely based on the buildings' cash flows. The value of Queen City hotels, hit hard by pandemic travel restrictions, collectively dropped by $15.3 million. The Burlington Country Club, whose value declined by $930,700, will pay 41 percent less than it did last year. The Innovation Center on Lakeside Avenue, the city's highest-appraised commercial building, will get a tax-bill reprieve of $15,743.

"Every dollar makes a difference," said Joe Carton, chief operating officer of Westport Hospitality Group, whose Hotel Vermont and Courtyard Marriott lost $18 million in revenue last year. Those businesses combined will pay $454,216 less after reassessment. "We're appreciative of the tax break. We know it probably won't last forever," Carton said.

Flynn Avenue resident Sam Beall didn't expect his taxes to go up because commercial property taxes went down. He doesn't think it's fair that businesses benefited from being assessed during the pandemic.

"I'm worried that we're locked into these tax rates for the next 10 years in a way that's unbalanced and not accurate," said Beall, who will pay $954 more in taxes. "I'm gonna be fine, but ... I worry about what's coming down the pike."

City assessor John Vickery acknowledged that the tax burden shift was greater than anticipated. At a city council meeting last week, he said the city should have better communicated to residents that certain neighborhoods could see larger tax bills. Vickery also announced that his office would reassess hotels next April, which could provide some relief to homeowners, and said the city may also take another look at office and retail buildings, depending on how quickly they bounce back from the pandemic.

Meantime, residents are figuring out how to make ends meet without additional state help. About 70 percent of Burlington homeowners get a state education tax rebate, but the amount is based on their income and home value for the previous year — meaning those with higher bills have to wait a year to get commensurate relief.

"It's certainly frustrating, especially with how high property taxes are in Vermont," said Jake Feldman, senior fiscal analyst with the state tax department. But, he added, "the people who are having these big bill increases are gonna get the credit they deserve."

That's little comfort to Schein, the Caroline Street resident, whose first tax payment was due last week. Like many homeowners, Schein met with a Tyler representative over Zoom earlier this year to appeal her home's new value but had no luck. Now, she's challenging her valuation at the Board of Tax Appeals, a citizen-run panel that will begin hearings next month. She's compiled what she thinks is an airtight appeal, a five-page report that argues her home "looks and feels old" compared to similar houses. Schein says that the three-story, renovated duplex down the street shouldn't pay half of what she pays per square foot.

If Schein's second appeal fails, she'll be faced with a hard choice: Either sell her home and leave her beloved neighborhood behind, or raise her tenants' rent more than they can afford. For Schein, there's no way to win.

The reassessment, she said, "throws my life plan really in doubt."

Going up

- Source: City of Burlington assessment data. Analysis by Sophia Hodson.

Colin Urban was sitting on the porch of his North Winooski Avenue apartment late last month when his landlord delivered the bad news. The property owner had made every effort to keep Urban's rent stable during the pandemic, he said, but the city's reassessment forced him to reconsider. Urban got the letter a week later: His rent would be going up $100 a month, to $1,270, on October 1. Rents for the building's three other one-bedrooms would also increase.

"He was like, 'You know, it's with a heavy heart that I have to do this,'" Urban recalled. "He really made it seem like he has no other options."

Urban can afford the extra cost, especially because he's splitting it with a roommate, but it's hard to stomach for a place that's not getting any nicer for his money. The floors of the building, built circa 1899, are still slanted. The place is poorly insulated, so the heating bill is high.

In Burlington, where renters constitute more than 60 percent of households, many will experience the trickle-down effects of higher housing values. Tenants are faced with paying more or moving out, and few apartments are available to choose from.

Olivia Taylor faced that dilemma in the spring, when she was apartment hunting with her partner. Every unit they liked was snatched up within hours. So Taylor resolved to stay put in the two-bedroom apartment on Ethan Allen Parkway that she shares with a roommate. But their monthly rent will be $150 higher, Taylor's landlord told her, because taxes are going up.

Taylor, who works as a consultant for an international development firm, took a side job with a catering company and started pet-sitting to make up the difference. Her roommate also works three jobs.

"It makes me very mad," Taylor said of Burlington's housing crisis, suggesting that the city needs to build more. The units that have come on line — such as the $1,400 studios at the Cambrian Rise development on North Avenue — are unaffordable for most renters, she said.

Indeed, according to the Out of Reach report, an annual publication by the National Low Income Housing Coalition, Burlington renters would have to make $24.33 an hour to afford a market rate one-bedroom apartment without spending more than 30 percent of their income on rent. Using that same standard, a minimum-wage earner could afford just $611 a month in rent, the report says.

Urban, who makes $30 an hour, said he barely breaks even every month after paying rent and credit card bills.

"For someone to live in Burlington who's making $15 an hour — where are they going to live?" Urban said. "How is that even feasible?"

Landlords describe a similar pinch. Emily Reynolds said she and her husband charge $1,200 a month for their two-bed, one-bath apartments on Riverside Avenue. But when their taxes went up by $2,883 this year, they upped their rates. The Reynolds had never raised rents on their tenants, one of whom has lived there for five years.

"These are people that we've known for a while and have been good tenants," Reynolds said. "We've never been in a situation where we're the evil landlords."

The Reynolds previously lived in the duplex but moved to Washington County five years ago when they realized they couldn't afford a single-family home in the Queen City. Now they're wondering if their rental property was a good investment.

Richmond resident Kyle Maxwell asked himself the same question when the tax bill for his triplex on South Winooski Avenue went up by $4,519 this year, a 23 percent increase. Maxwell said he didn't raise the rents after he bought the building in April but will have to ask about $125 more a month from each unit just to stay solvent. Rent for the three-bedroom unit in his building is already $2,400.

"I would be hard-pressed to afford it. I know that. So I wouldn't blame anybody for needing to move," Maxwell said. "I think we'll see a lot of changing of hands and changing of keys in the coming years as these leases expire and people are looking at 10 percent increases in their rent."

The Champlain Valley Office of Economic Opportunity's free tenant hotline has gotten more calls about landlords hiking rents during the pandemic. Jess Hyman, associate director of its housing advocacy programs, worries that because renters' wages haven't risen at the same rate as their housing cost, "there's no way to keep up" with other expenses.

"If someone's prioritizing paying their rent, and half of their income or more is going toward rent, that doesn't leave enough for food or health care or childcare or car payments," she said. "That has a ripple effect on the rest of their lives."

Hyman said Burlington's tight rental market has long made marginalized communities more vulnerable to discrimination. With such high demand, landlords can be choosy about their renters, which can allow implicit bias to creep in, Hyman said. If rental rates continue to increase, she said, that would exclude "even more people."

"People will be living in situations that may not be safe," Hyman said. "It makes it really tough, especially for families, especially for folks who are already really struggling."

'The randomness of this'

- Luke Awtry

- Deena Frankel

After the value of their Pine Street home nearly doubled to $477,000, Deena Frankel and her husband, Gregory Dana, got to work preparing an appeal. They spent 20 hours reviewing the values of other single-family homes in their neighborhood and looked for flaws in the data collected by the city's consultant, Tyler Technologies.

Though the work was tedious, it was familiar to Frankel and Dana, both of whom are retired but did analytical work during their careers. They had just 15 minutes on Zoom to try to convince a Tyler representative that their value was too high.

"We felt they didn't have an understanding that the South End isn't all one neighborhood," Frankel said. "One of the key things we looked at was that lack of nuanced understanding of the neighborhood. And they kind of admitted that in the course of the hearing."

Frankel and Dana succeeded, at least partially: The city ultimately knocked about $44,000 off their home valuation, though the couple's new tax bill is still significantly higher than it was last year.

"It's still costing us $2,000 more," Frankel said.

Yet Frankel and Dana were among the lucky ones. Of nearly 1,500 residential property owners who appealed their assessments, values decreased for only about 450, or 30.5 percent. And several homeowners who appealed told Seven Days they found the process confusing and arbitrary, with no explanation for the ultimate decisions.

"I totally believe in taxes, and I totally believe in contributing to the greater good, and I want to keep doing that," said Zpora Perry, whose taxes on her Locust Street home went up about $2,600. "I just want it to be a process that's fair and equitable and transparent, so we know who's paying it and who's getting out of paying it."

Perry's first experience with Tyler didn't inspire confidence. Her property's assessment had increased $220,000 over its value from 2015, when the city last reassessed it after she and her husband built a 400-square-foot accessory dwelling unit, or ADU, for her parents in the backyard.

When appealing, Perry and her husband compared their property to others with detached ADUs. Some of those values were calculated differently: While the price per square foot of Perry's ADU was higher than for the main house, the square footage of the neighbors' ADUs were lumped in with the main house and calculated at the same rate, she said.

During the couple's appeal session on Zoom, the Tyler rep didn't introduce himself until prompted, then said, "I'm just the monkey," Perry recalled.

"I wrote it down because I was so shocked," she said.

The rep then "said a few other self-deprecating things" and made small talk before Perry and her husband got him back on track to discuss the matter at hand. They asked him if he'd received their appeal document, which they'd filed through the city website; he said no. When they broached the issue with their ADU, the rep was confused.

"He said, 'What's an ADU?'" Perry recalled. "We were like, 'Uh, an accessory dwelling unit?'" And he was like, 'What's that?'"

Before the couple knew it, their 15 minutes were up. Later, they received a letter that said their value was unchanged, but Tyler didn't provide any explanation. They've filed another appeal to the city's Board of Tax Appeals.

- Luke Awtry

- Zpora Perry and her daughter, Lyle Johnson

At the city council's August 9 meeting, Councilor Chip Mason (D-Ward 5) excoriated Tyler, saying he's "heard nothing but extreme negative things from every constituent" who contacted him about their appeal. "We're getting some of the most emotional and frustrated emails I've received in 10 years," Mason said.

Alex Friend, meanwhile, had a far different — and more rewarding — experience. He thought his Henry Street valuation was way out of whack and compiled data on comparable houses and recent home sales, which he argued were driven by a pandemic bubble that was not representative of his property's actual worth on the market.

Friend sent in his documentation before the hearing.

"On the morning of the appeal, we spoke with somebody from Tyler Technologies, and he said, 'Yeah, I read your appeal, and I agree with that. I'm going to take down your valuation,'" Friend said. "And we were all prepared to say, 'But ... but ... but!' But we didn't have to say anything."

The assessors lopped about $116,700 off Friend's assessment.

"That's what really strikes me, is the randomness of this," Friend said. "It seemed like it worked well for us, but not for other people."

Nearly one in five of all property owners appealed their new assessments, but Vickery, the city assessor, defended the assessment process and the company that carried it out. Tyler completed the city's 2005 reassessment, too. That year, it sent a representative to view every property. Those reps only managed to get into about 50 percent of homes, Vickery said.

Tyler visited only a few homes in 2020 before the pandemic hit. Its employees reviewed city records, sales data, photographs taken from the air and city streets, and market analysis to come up with its valuations. The company obtained some home measurements, such as square footage, by using computer software to examine digital photographs of the buildings.

Sending a person to each property is "old-fashioned," said Vickery. Some communities still favor that method, however; South Burlington hired Tyler to reassess its properties using in-person checks. The city paid about $400,000 for the review; homeowners were notified about their new valuation in June.

Rates of appeals show that South Burlington property owners were less likely to challenge their new assessments than Burlington residents were. About 9 percent of SoBu taxpayers appealed to Tyler, compared with roughly 18 percent of Burlington's.

Blane Bowlin, Tyler's project manager for both cities' reassessments, did not respond to messages requesting comment.

"The change in values, by and large, are correct," Vickery said. "And there's always a few issues that get missed or not addressed. I anticipated that, and I know there will be some work to put a fair value on every single property."

Some homeowners, though, worry that even the appeals process missed important information. Sebastian Ryder and her husband, Jeff Bower, saw the value of their modest North Champlain Street home leap by $101,500. But the assessors counted a full, finished basement, while the couple said they have a small dirt crawl space. Tyler also miscalculated several rooms' square footage.

Bower sent a list of mistakes to the consultant, but the company denied his request for a change. He and Ryder did not file another appeal.

The increased valuation, coupled with a steep drop in the payment they get from the state, means Ryder and Bower will pay about $3,660 more in taxes this year, a significant amount for a couple earning around $65,000 annually, Ryder said. She could stomach the increase if the city were providing the services she expects. Instead, Ryder said, she's been unable to summon the police to what she described as a nearby drug house.

"I want to be safe," Ryder said. "I want to feel like I can walk from my front door to my car without being screamed at by a neighbor."

"We're not asking for the world here," she added.

Right timing?

- Luke Awtry

- Wanda Hines

Hines, the Old North End resident, wanted to do something for herself this summer. Her children have moved out, and she hoped to use her small savings to finally purchase a health insurance plan. At the very least, maybe she could fix her tired roof, the raggedy awning above her front door or the leaky kitchen sink. She'd even priced a trip to Mississippi to visit family.

Then she got her tax bill. Hines will pay twice what she did last year for her home on the corner of Oak Street and Intervale Avenue. Now her plans are off the table.

"There will be a little less joy in my life," Hines said. "A little less joy for Wanda."

Hines is one of those questioning why the city would conduct a reassessment during a disruptive pandemic. Others are wondering why the city waited 16 years to reassess properties, as home prices steadily climbed.

Many municipalities wait until the state orders a reassessment, but towns can initiate the process whenever they want, said Casey Michael O'Hara, program manager for the Vermont tax department's Division of Property Valuation and Review. O'Hara pointed to national standards that say towns should "reinspect" property values every four to six years. The state recommends waiting no more than 10.

"If you've waited that long, you're likely going to see a pretty significant increase" in property values, he said, adding, "the markets are dynamic, and they're always changing."

City Councilor Sarah Carpenter (D-Ward 4) said the city should reassess properties more often, despite the cost. Carpenter, who ran the Vermont Housing Finance Agency for 20 years before being elected, said this reassessment demonstrated how suddenly the tax burden can shift.

"You need to do it as often as you see trends, and changes in trends," she said.

Carpenter was less convinced that the city should have halted the process mid-pandemic but noted that many of her constituents disagree. No one knew how long the pandemic would last, and Burlington would have been out of compliance with state orders, she said.

Both Mayor Weinberger and Vickery, the assessor, say the city was right to soldier on because it had a standing contract with Tyler and a state-mandated finish date of April 1. But the officials disagree on whether Burlington should assess properties more frequently.

Weinberger said he's unconvinced that it would be better for taxpayers to endure more regularly a costly reassessment, which he called "disruptive and challenging." The mayor also noted that the city hasn't waited for a state mandate to address inequalities on a smaller scale. Both multifamily housing and lakefront properties have been reassessed since 2005, Weinberger said.

"[That] has actually reduced the tax burden in between reappraisals for all other taxpayers," he said. "I think that's a pretty good strategy."

Vickery, however, said he thinks more frequent citywide reappraisals would keep values more equitable and aligned with the market. If the market continues its upward climb, and Vickery said he expects it will, the city may need another reassessment before 16 more years pass, he said.

'Facing the precipice'

- Luke Awtry

- Mark Montalban

Alan Bjerke opened the Board of Tax Appeals meeting on July 28 with a warning.

"It's going to be a busy fall, so enjoy your August," Bjerke, the board chair, said to nervous laughter.

He wasn't kidding. More than 640 property owners filed a second challenge of their valuation in front of the board, which is made up of seven members of the public and three city councilors. The board will split into three groups to hear the appeals — collectively holding 20-minute hearings 18 times a day, three days a week, for 11 weeks. The process could take until December.

Vickery said not everyone will be satisfied, though he thinks "a lot of people will be." Those who still have objections to their valuation can take the city to court.

As the board wades through its stack of appeals, Mayor Weinberger is focusing on other solutions. In the short term, he's directed department heads to find relief for low-income homeowners, including potential one-year grants to supplement their lagging state rebate. This fall, Weinberger will host his third summit focused on addressing the city's housing shortage.

Weinberger, a former developer, said the city's housing stock has increased by 1,500 units since he was elected in 2012 — "a historically large number," he said, "but it's not enough." The mayor said city zoning should allow more than one structure to be built on most city lots.

"We need to become one of the growing list of cities that takes dramatic, dramatic change with our local land-use laws," Weinberger said. "If we are serious about making housing a human right, if we're serious about stopping this upward pressure of housing valuations, that is the only way. We need to create a lot more homes."

Meantime, the existing conditions have become untenable for some residents. Katherine Taylor-McBroom and her husband decided to put their Home Avenue house on the market as soon as they got their new tax bill last month. The couple thought Burlington was getting too expensive before the reassessment, and their $957 annual increase convinced them it was time to move back to Taylor-McBroom's native Tennessee.

"I didn't want to leave, because I feel safe here ... But I'm ready to go now. At some point, you're just like, OK, it's not worth it anymore," Taylor-McBroom said. She worries that the city is becoming out of reach for many.

"Burlington is going to be either low income [or] high income," she said. "There's not going to be any middle class."

Mark Montalban was struggling financially before the reassessment upped his New North End home's value by $98,000. A single parent of a child with disabilities, Montalban took home $24,400 last year, including the federal stimulus checks sent out during the pandemic. The temporary $250 monthly federal child tax credit is helping, but Montalban is still behind on his utility bills, and now he owes about $800 more a year in taxes.

"I'm just making it by the skin of my teeth," he said.

Montalban operates Green Acres Homestead, an urban homesteading venture in which he grows vegetables and makes kombucha, herbal salves and more out of his home. He's invested in solar panels and has a greenhouse. His son, who has autism and special needs, feels safe and stable here. He can't just pack up and leave.

Instead, Montalban is squirreling away the proceeds from this summer's farmers markets and preparing for the winter slowdown. Focusing on the task at hand keeps his worries at bay.

"If I thought about it too deep, it would freak me out," he said. "I'm in survival mode."

But there could be more increases on the horizon. The Burlington School District is considering building a new high school, and the city council is pondering a switch to consolidated waste pickup, which would require multimillion-dollar bonds. Weinberger is weighing whether to ask voters this fall to approve a revenue bond for the Burlington Electric Department's energy-efficiency programs. The mayor says he's committed to keeping tax rate increases within the rate of inflation, as he has since he was first elected.

"That's going to continue to be my guiding star," Weinberger said. "I'm going to find a way to do both."

The mayor's talking points on affordability only make Schein, the Caroline Street resident, even angrier about her situation. She wishes the administration had prepared residents to pay higher taxes, and that the city had reassessed properties more often so increases could be absorbed over time. Had that happened, Schein said, she wouldn't feel as she does now, like she's "suddenly facing the precipice."

Schein has emailed legislators, contacted city councilors and posted on Front Porch Forum about the reassessment. She's anxiously awaiting the date of her second appeal.

"If I haven't taken every step and wailed loud at every person that I can, I won't have done myself the justice of trying every last thing," she said. "Until then, I'm just trying not to panic."

Sophia Hodson contributed data analysis for this story.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.