- Tim Newcomb

Twenty thousand Vermonters will lose their unemployment benefits on December 26 if two federal programs that expanded the social safety net amid the pandemic are allowed to expire.

Vermont cannot afford to extend the programs itself, and while federal lawmakers have said for months that they support renewing them in some way, negotiations in the partisan-paralyzed Congress appear no closer to a resolution. With the deadline approaching, each day without a deal nudges families closer to the edge.

"Even a week without income is too much for most people," said Stephanie Yu, deputy director of the progressive-leaning Vermont think tank Public Assets Institute. "Most people are living paycheck to paycheck."

They include people such as Stella Maher, who has been on unemployment since losing her bartending job in March. The Killington resident stashed away as much as she could when her benefit checks still included a $600 federal pandemic supplement that ended in the summer. Since then, her savings have dwindled as she tries to keep up with a list of monthly expenses that includes a $180 student loan payment and $1,400 in rent. Maher's bank has sent her several notices that she's dipped below $100 in her account, and she's now racking up credit card debt as she wonders how much worse her situation might get next year.

"It's never a place you want to be," she said.

A growing sense of desperation is becoming evident during calls to the Vermont Department of Labor's unemployment center. Employees there sometimes field calls from angry or distraught claimants: "people who have, at times, threatened to harm themselves or harm others," Labor Commissioner Michael Harrington said last week. But while such calls were rare before the pandemic, the department is bracing for many more. The state has even brought in the Department of Mental Health to train call-takers on how to deal with Vermonters in crisis — "in recognition of what's coming," Harrington said.

The two expiring unemployment programs are part of a series of emergency stimulus measures Congress passed in the spring — spending that also included direct checks to most households and the $600 weekly supplement to existing unemployment benefits. The financial blitz helped many Americans withstand sudden job losses or unanticipated expenses. But much of that assistance dried up over the summer, and studies have found that millions more Americans have plunged into poverty as a result.

According to a recent survey from the University of Vermont, nearly 30 percent of Vermont households were food insecure at some point between the months of March and September. Households that suffered job losses or disruptions — about 46 percent — were more than twice as likely to report food insecurity.

The demise of the unemployment programs could have even more dire impacts. Many families have already run through their savings. And while some are receiving unemployment benefits because they are working fewer hours than usual, others have no work whatsoever. Once the checks disappear, so too will their income.

The threat of losing benefits comes as the coronavirus surges, raising fears of another crippling shutdown that would lead to another wave of massive layoffs. The first week of December spawned more virus cases in Vermont than did the months of June, July, August and September combined. Officials are hopeful that recent restrictions on travel and multi-household gatherings will slow the surge. But more restrictions could soon be necessary.

"We're still figuring out if we've seen the worst yet," Yu said.

As of last Friday, about 8,500 Vermonters were enrolled in the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program, which Congress created in the spring to cover people left out of the traditional unemployment system: gig workers, part-timers, freelancers and the self-employed, as well as those unable to work because of pandemic-related childcare or health issues. The program calculates payments based on past average wages and allows people to receive partial benefits even if they are still working, as long as they are taking in less money than they typically would.

Another 9,000 people are receiving payments through the Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation program, which offers an additional 13 weeks of benefits after 26 weeks of state jobless benefits.

Some people currently qualify for yet another 13-week extension program unrelated to the pandemic. But Vermont's reported unemployment rate has reached a low enough level that the state will likely not be eligible for that program by the end of the month.

All told, the Department of Labor anticipates that up to 75 percent of roughly 28,000 people now on unemployment will lose benefits once the federal programs expire.

Sarah Adams, 41, applied for the pandemic assistance program after she was forced to close her cleaning business in mid-March. The Bridgewater resident stopped claiming benefits once her business returned to full operation in July. But the business, which relies on second-home owners, took another hit after Gov. Phil Scott reimposed travel restrictions last month.

Adams has started filing for unemployment again while she forgoes some pay from her business. She had hoped that claiming the partial benefits would allow her to assign the few clients she has left to her employees and therefore save some jobs. But after learning in an interview with Seven Days last week that benefits for self-employed people would expire around Christmastime, Adams said she would likely have no choice but to let go of most of her employees — whom she considers family — "so that I personally can go out and clean homes and earn more money."

"It's extremely stressful and depressing," she said.

Other self-employed people are making similar calculations. Jay Vos, a 72-year-old Burlington man who runs a dog-walking and -sitting business, said weekly unemployment payments, on top of Social Security and a pension from a previous job, have helped him stay afloat after his client list shrank dramatically. With his benefits set to expire, "It's going to be a struggle paying my rent, paying my utilities, the upkeep of my car," he said.

Vermont leaders are well aware of the impending benefits cliff but say there's nothing they can do. Though Vermont has roughly $250 million left in its unemployment fund — a little over half of what it was when the pandemic began — federal restrictions prevent the state from using that money to replace the federal benefits. Officials say it would be impossible for a state the size of Vermont to find an alternative funding source.

"We don't have the resources," Scott said during a press conference last month. "We're talking about tens of millions of dollars every single week."

Indeed, the Vermont Legislative Joint Fiscal Office reported last week that the federal government had pumped nearly $100 million into the state through the two expiring programs as of October 20, a total that is likely far higher now as more and more people exhaust their state benefits. That's on top of the $600 million injection from the now-expired $600 weekly payments.

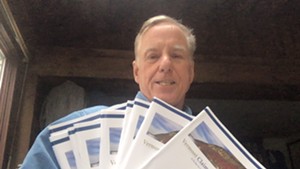

Scott has expressed frustration at federal lawmakers' inability to reach a deal to extend the programs. On Monday, he and four other Republican governors released a letter demanding that Congress pass a relief bill by the end of the month.

"It may not be everything they want," Scott said in November. "But just as a stopgap measure, there's a number of initiatives they should be working on right now to help."

"I'm pleading with them to get back to work," he added.

There is still a chance that Congress will extend the programs before they expire. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) has called a new aid package one of the chamber's top priorities, saying at a press conference on November 4 that he hoped the "partisan passions that prevented us from doing another rescue package will subside with the election."

"I think we need to do it, and I think we need to do it before the end of the year," he said.

Yet there remains no clear picture of what the new benefits package would look like. Last week, a bipartisan group of lawmakers introduced a $908 billion plan that would provide, among other assistance, four months of $300 a week in extended unemployment benefits. Some top Democratic leaders endorsed the plan. But others, including Sens. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) and Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), oppose a provision intended to shield companies from coronavirus-related lawsuits. Sanders also criticized the proposal for lacking stimulus checks, saying in a statement that tens of millions of Americans "would receive absolutely no financial help from this proposal."

McConnell, meanwhile, instantly shot it down, implying that he thought it was something President Donald Trump may not sign. "We have no time to waste," the Republican leader said.

McConnell instead proposed another version of his slimmed-down stimulus package that has already failed twice to advance in the Senate. His $500 billion plan contained far less support for the expiring unemployment programs, extending the benefits only a month before phasing them out over a two-month period during which no new claimants could be accepted.

As the partisan squabbles continue in Washington, D.C., more and more Vermonters are realizing their benefits will soon expire.

People on unemployment must usually prove that they are actively searching for jobs each week, but the state suspended that requirement early on in the pandemic. The Department of Labor has started urging Vermonters who are able to work to begin looking for new jobs, flooding social media with posts about job fairs and apprenticeship programs.

For people with personal health concerns or those without childcare, however, finding a new job may not be an option right now, said Yu, of the Montpelier think tank. "There's so many reasons why people might not be able to work," she said. "They're forced to make really difficult choices."

Some are now reaching out to a help hotline called COVID Support VT, which the state launched with Vermont Care Partners in October to provide counseling services to Vermonters in need. Alex Karambelas, one of the hotline's counselors, said many recent callers have described severe financial distress due to the approaching deadline. Most say it is the first time they have experienced such upheaval.

One woman in her late fifties was in crisis because she had been unable to find work since being furloughed from a job in the restaurant industry, where she has spent her career. "Her concern was that she's currently left without the skills or the education to pivot," Karambelas said.

Karambelas understands her callers' plight better than most: She herself lost a restaurant job in March and spent about five months receiving unemployment — payments that she used to cover expenses for both herself and her mother. She recalled the concern she felt when the $600 payments were set to expire this summer. And while her new job is to support people — to explain that even though they may feel powerless, there are ways to manage their stress — she cannot help but lament what is beyond her control.

"There is a solution to this problem, and the solution lies with the federal government. It's up to them to take the initiative to help people right now," she said. Otherwise, "things are going to get dire."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.