- James Buck

- James Pocock

James Pocock had been spending his nights huddled in a downtown Burlington ATM vestibule when the coronavirus arrived in Vermont. On March 18, an acquaintance told him that the state had agreed to temporarily house people experiencing homelessness in hotels and motels in order to keep them safe.

"I said, 'All right. I'll get a night,'" Pocock recalled. "And I just never left."

That is, until last month, when the 50-year-old Ohio native moved out of the Quality Inn Colchester and into a one-bedroom apartment in Essex. "It's something I've been wanting for a long, long time," said Pocock, who has been homeless on and off since 1989. "I've never signed my own lease before."

Pocock is one of hundreds of Vermonters likely to end up with more stable housing as a result of the pandemic, thanks to a $95 million infusion of federal coronavirus aid in the sector. By the end of the year, according to state officials and their nonprofit partners, the money will have funded the construction of 243 new housing units and the rehabilitation of 216 existing apartments. The aid is also going toward upgrades of 12 shelters, ensuring that they can safely serve clients even during a global pandemic.

The largest of these projects is Champlain Housing Trust's conversion of a Baymont Inn & Suites on Susie Wilson Road into a 68-unit affordable housing complex rechristened Susan's Place, which Pocock now calls home. Last week, he admired the sprawling, baby blue building from a gazebo in the facility's parking lot, sitting on his walker and puffing on a cigarette.

"COVID is a horrible thing, but in some regards, it's been a huge blessing for me," Pocock said.

Others haven't been as fortunate.

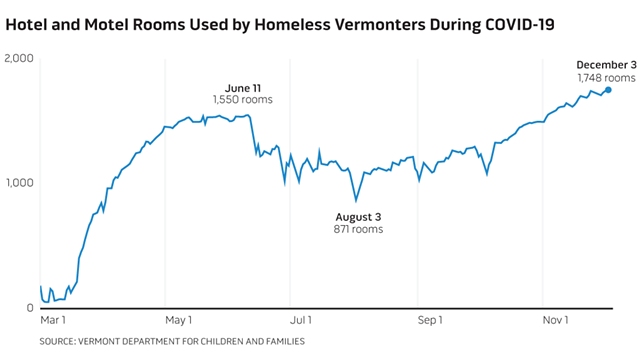

In recent weeks, the number of housing-insecure Vermonters receiving state vouchers for hotel and motel rooms has surged. According to the Department for Children and Families, which administers the program, a record 2,483 people — including 417 children — were living in 70 such facilities around the state as of early this week. The cost of the 1,770 rooms, according to DCF senior adviser Geoffrey Pippenger, was roughly $140,000 a night, or $4.2 million a month.

"It's the exact right thing to do, but it's not sustainable," said Chris Donnelly, Champlain Housing Trust's director of community relations. "I hope it leaves people with their eyes open — that we have a much bigger housing crisis than people thought."

Advocates have long feared what might happen to those living in hotels and motels once the December 30 deadline to spend federal coronavirus aid passes. But in recent weeks, state officials have quietly made clear that they will continue dispensing housing vouchers until the public health crisis subsides. At a press conference last Friday, Human Services Secretary Mike Smith suggested that the expanded program could continue until at least July 2021. According to Pippenger, the Federal Emergency Management Agency is expected to foot much of the bill, though the state will have to provide a 25 percent match.

The program's extension is a relief to those who believe it has kept housing-insecure Vermonters safe throughout the pandemic. According to the state Department of Health, only six people experiencing homelessness have been diagnosed with COVID-19, and none has died from the virus.

"The governor wants everyone to stay safe at home — and you need a home to stay safe," said Erhard Mahnke, coordinator of the Vermont Affordable Housing Coalition.

The state program, formally known as "General Assistance temporary housing," long predates the pandemic. But before last spring, when the state waived many eligibility requirements, it rarely served more than 250 households a night, according to Pippenger.

Though the program has been criticized over the years as a waste of state resources, Mahnke called it "a godsend" that it was already in place when COVID-19 arrived in Vermont. "It may not be a solution to homelessness, but it's certainly something that's needed for our homeless and vulnerable Vermonters," he said.

Other state initiatives funded by federal coronavirus aid have kept Vermonters from losing their homes in the first place. The legislature earlier this year appropriated $25 million for rental housing assistance, $4 million for mortgage assistance and $8.5 million for utility arrearages, according to the Joint Fiscal Office.

All three forms of aid are scheduled to expire later this month, as are some unemployment payments, raising the prospect of yet another wave of homelessness. That would likely be compounded when, a month after the state of emergency eventually ends, Vermont's eviction moratorium lapses.

"We're trying to assist folks with some pretty severe challenges with short-term funding when what they'll probably need is long-term assistance," Mahnke said.

According to Pippenger, "a constellation of factors" is driving the current rise in use of the hotel and motel program — including financial desperation, a resurgence of COVID-19 and the onset of winter. "The super short answer to why things are increasing: It's complicated," he said.

Those enrolled in the program are scattered around the state — in rural motor inns and crowded chain motels. The facility housing the most recipients is the Holiday Inn Burlington, just off Interstate 89 in South Burlington. It has closed for regular business to accommodate the new clientele, who numbered 134 last week.

Since May, the state has contracted with the Champlain Valley Office of Economic Opportunity to provide wraparound services to the hotel's residents. Case managers work to find them stable housing and jobs, while other nonprofits host medical clinics and needle exchanges. Hotel staff continue to run the front desk and clean the rooms once a week.

"It's just a lovely and respectful alternative to the shelter system," CVOEO's Holiday Inn program director, Dave Gunderson, said last week in his conference-room-turned-office near the hotel's lobby, where residents dropped by to meet with his colleagues. "This seems to show that we can do better. It's just a matter of whether we choose to."

Not everyone is enamored of the arrangement. Neighboring businesses have complained that the program has brought drugs, disorderly conduct, theft and plenty of sirens to the area. The South Burlington Police Department has responded to 380 incidents at the hotel since May, according to Chief Shawn Burke. In October, he said, a resident died of a suspected opioid overdose.

"That's not shocking from a public safety perspective when you think about the population that's there," Burke said, arguing that the same activity would likely take place elsewhere if the hotel's residents were dispersed.

Though responding to calls from the Holiday Inn has drained his department's resources, Burke praised CVOEO for working collaboratively to address problems and providing its own clinicians and security. "I think this has been a good strategy," he said. "I just know that, long term, it's very, very expensive, and I don't know what the endgame is going to be."

For Sara Carroll, the Holiday Inn has served as a life raft. Before moving in last May, the 42-year-old Burlington native had been couch-surfing and living on the streets for much of the previous three years.

"I started experimenting with some drugs with my previous boyfriend, and I got in too deep," she explained. "I lost custody of my child to her father, and I kind of went overboard: lost my car, lost my apartment, lost my job, lost everything. Suffered a really bad overdose, which opened my eyes, and I've been clean since."

At the Holiday Inn, Carroll has worked with counselors to access group therapy and is attempting to sign up for federal disability assistance. "I hate asking for help, but it's here," she said.

Most importantly, according to Carroll, the Holiday Inn has offered a safe and secure place to sleep. "It's nice not to have to worry about where I'm going to lay my head at night," she said. "It's nice to have this place."

Carroll won't be there much longer. She recently learned that she, too, had secured a room at Susan's Place. "I'm pretty psyched," she said.

- James Buck

- Susan's Place

Even as residents move into one wing of the former Essex motel, named for the late Champlain Housing Trust social worker Susan Ainsworth-Daniels, remodeling continues on another. Last week, workers scurried around, noisily completing the renovation.

According to Donnelly, the Champlain Housing Trust bought the building in October for $11.6 million and had just months to convert its 124 rooms into 68 apartments, at a cost of $900,000.

"It's amazing," Donnelly said of the speed with which Susan's Place came together. "To do this in three months is wacky — and that's a technical term."

Throughout the state, affordable housing organizations have been rushing to finish similar projects by the end of the year. Though most such developments typically take two to three years to complete, those funded with federal coronavirus aid had just six months.

"Some are going to be a race to the finish line," said Vermont Housing & Conservation Board executive director Gus Seelig, whose organization was charged with distributing roughly $34 million for new housing and improved shelters.

The projects include a 33-unit shelter operated by ANEW Place at Burlington's Champlain Inn and a 21-unit shelter in Colchester run by Steps to End Domestic Violence. South Burlington's Ho Hum Motel will serve temporarily as a COVID-19 isolation and quarantine center and will later become affordable housing. Elsewhere in the state, nonprofits have been working to create housing in a former John Deere store in Rutland, a mobile home park in Bradford and a German chalet-style lodge in Brattleboro.

"It really took a lot of creativity to find those projects and make them happen," said Jennifer Hollar, VHCB's director of policy and special projects.

Her organization required that affordable housing developers develop long-term funding plans for each of the new facilities. Though federal coronavirus aid can be used to purchase and remodel buildings, their new owners are on the hook for wraparound support services. Local and state housing authorities will help low-income residents access federal assistance, such as Section 8 vouchers, to help pay the rent.

Pocock, who lost the use of his left foot after a surgery last year, applies a portion of his disability benefits as rent for his one-bedroom apartment at Susan's Place. Though he worked for years as a cook at Chittenden County restaurants, he currently has no other form of income.

Substance use contributed to Pocock's slide into homelessness, but he said he hasn't touched methamphetamine in 20 years, nor crack cocaine in 10. "And I'm keeping it that way," he said. (Pocock does call himself "a BB guy: beer and bud" and wears a camouflage hat featuring a marijuana leaf and the word "Weed!")

During his stay at the Quality Inn Colchester, Pocock witnessed plenty of hard drug use, he said, but he doesn't plan to tolerate it if he sees the same at Susan's Place.

"This is my neighborhood now. This is where I live," he said as he led a reporter to his second-floor apartment. "I ain't gonna allow that crap around here."

Pocock said he already feels at home, though he hasn't yet slept in his new bed. After years of living in a tent in the woods and on the streets of Burlington, he feels more comfortable in his sleeping bag on the floor. "Old habits die hard," he said.

Inside his apartment, which he entered with a key card, were early signs of Christmas: multicolored lights on a window and tinsel on a door. Two stockings hung from a television.

"Home, sweet home," Pocock said with a grin on his face.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.