- Bear Cieri

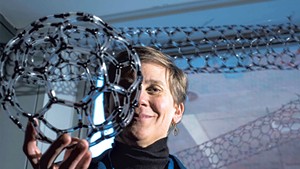

- Kirk Dombrowski

The robots will begin their mission when the snow melts next spring. Some no larger than a quarter, the insect-like devices will crawl under bridges, swim into storm drains and climb power lines — targets that are inaccessible to their human overlords. Swarms of these so-called "micro-robots" will deposit wireless sensors to monitor the structures' resilience to strong winds, heavy rainfall and other environmental forces, feeding data back to researchers on the ground.

The four-year study, led by University of Vermont mechanical engineering professor Dryver Huston, won a $4 million grant from the National Science Foundation earlier this month. The application was competitive, with a one-in-four chance of winning, Huston estimates. He owes his success to a newfound commitment to research at UVM, the likes of which he hasn't seen in his 34 years on campus.

"The plan is to try and compete for more of these big grants," Huston said. "It's an investment that sometimes pays off."

The man with the plan? Kirk Dombrowski, who runs UVM's Office of the Vice President for Research. The office manages grant awards for all seven colleges at UVM, and as vice president, Dombrowski is in charge of tracking the spending and overseeing the office's 140 employees.

A transplant from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Dombrowski arrived in Burlington in April 2020 and immediately made his mark. For the fiscal year that ended in June, UVM attracted $227 million in research funding — an all-time high that easily eclipsed the previous year's $181.7 million record haul. Before Dombrowski, UVM wouldn't have dreamed of reaching that number, said Dan Harvey, the research office's director of operations.

"We all would have said, 'You're out of your mind. That would never happen,'" Harvey said with a laugh. "But it did, and a lot of it is because of him."

Not only has Dombrowski broken records, he's also built a foundation for success, his colleagues say. Early on, Dombrowski hired a team of grant writers who collaborate with faculty to apply for funding, and he helped open a brand-new Office of Engagement on campus to assist small businesses in doing the same. This month, he convinced the state's energy leaders to join forces to apply for a slice of the federal infrastructure bill.

Dombrowski hopes his work has a tangible impact on UVM's campus, the city of Burlington and beyond.

"I think that universities are transformative to the communities around them," Dombrowski said. "We need to show people there remains a huge benefit to higher education, not just for the people who are in it."

Dombrowski grew up in Gloucester, Mass., and came back East after nearly seven years at Nebraska-Lincoln, where he taught sociology and served as the associate dean for research. A trained cultural anthropologist, Dombrowski has studied how to slow the spread of HIV in rural Puerto Rico and how to prevent suicide among Indigenous people.

At Nebraska-Lincoln, Dombrowski organized teams of researchers to go after big grants. One $12 million award from the National Institutes of Health funded the university's Center on Rural Addiction, which studies substance use in the rural Midwest.

UVM's Office for the Vice President for Research has existed for years, but few people off campus know of it — a reputation Dombrowski is working to change. His department is the go-to place for faculty members seeking both research grants and private equity to bring their inventions to market.

It helped launch Benchmark Space Systems, a startup founded by UVM grad Ryan McDevitt. Formed in 2017, the company builds technology to propel small satellites. In June, Benchmark's products were used for a rocket launch by SpaceX, the aerospace outfit run by Tesla cofounder Elon Musk. (For more on Benchmark, see page 39.)

"That's the ideal goal," Harvey said. "UVM faculty [and students] create something really cool, and then we figure out how to help bring it to market and create jobs and further cement UVM's role in the community as a catalyst."

Dombrowski has taken that mission to heart. When he arrived at UVM, the research office had just one grant coordinator to assist faculty such as Huston to write major applications. Now there are six. They help make completing the applications, some of which are 300 pages long, slightly less daunting. Dombrowski also brought in a Washington, D.C.-based consulting firm to find lesser-known grant opportunities.

Huston said he likely wouldn't have won funding without the support. He's pleased that UVM is propping up other disciplines instead of just focusing on its Larner College of Medicine, the biggest grant-getter.

"Kirk has tried to say, 'OK, can we bring the rest of the campus up to that level of activity?'" Huston said. "That's the mentality."

Dombrowski's goal is to elevate UVM to one of the nation's most prestigious research institutions — specifically, those conferred with the coveted "R1" designation from the Carnegie Commission on Higher Education. Since 1970, the organization has classified colleges and universities using benchmarks that have changed over time. Most recently, in 2018, the commission gave the R1 label to just 131 universities that participate in "very high research activity."

R1 schools include Dombrowski's former one, Nebraska-Lincoln, and Purdue University in Indiana, where UVM president Suresh Garimella previously served as the VP of research.

When UVM hired Garimella in 2019, he took the helm of a university divided over recent cuts to its humanities program. Students and faculty staged a protest, criticizing UVM's budgeting model that shifted funding from the liberal arts to science, technology, engineering and math, or STEM. Late last year, UVM proposed cutting more than two dozen programs from its College of Arts and Sciences but later found the cash to save many of them.

Dombrowski says investing in non-STEM areas is key to reaching R1 status. Qualifying universities, he said, have to show that their research funding is comprehensive and includes a wide range of academic disciplines. UVM is currently an R2, just one step removed from the R1 status, but the step up would signal to funders that it's "a world-class research university," Dombrowski said, "not just a place that does some really good medical research."

UVM has struggled to keep all-star faculty who feel limited by the school's research opportunities, Dombrowski said. Joining the elite classification could attract talented, more diverse faculty and graduate students, he said. In other words, the label would give people a reason to come to Vermont — and stay.

"It has a lot of immediate positive implications," Dombrowski said. He hopes to meet the standard by 2024.

His colleagues say Dombrowski's fast-paced, innovative style is refreshing. Dombrowski says he simply encouraged his office to be more proactive — not just managing grants but also competing for them.

His workplace philosophy is equal parts aggressive and forgiving.

"I want them to try things that might fail," Dombrowski said of faculty. "[We're] trying to give people credit for the innovation of the ideas rather than their success or failure."

Dombrowski has also supported partnerships with UVM's neighbors.

In 2019, Harvey, Dombrowski's chief of staff, began working with the Burlington Electric Department to build a solar research facility at the city's McNeil Generating Station using decommissioned solar panels. The city will provide the space for free and is already storing the equipment at McNeil. UVM, meanwhile, will pay $150,000 to cover the permits and construction, and will provide the power to McNeil's joint owners — BED, Green Mountain Power and the Vermont Public Power Supply — at no cost. The facility is scheduled to open next year.

"UVM can play a really important role in developing technologies that can help us with reducing emissions and managing energy use," BED general manager Darren Springer said. He hopes that the facility will inspire students to look for jobs in the clean energy sector after graduation.

In the summer of 2020, Dombrowski helped set up the new Office of Engagement, which is charged with bolstering Vermont's skilled workforce. The office, which UVM calls "the university's front door," helps private companies write grants, hosts business roundtables and sets up paid student internships. In less than a year, the office created 365 of these internship positions.

Earlier this year, UVM undergrad Skylar Bagdon started a new program — Academic Research Commercialization, or ARC — through which teams of students partner with inventors to create startup companies. The fledgling initiative got off to a good start, but when Dombrowski learned that it needed funding to continue another year, he hit the phones.

"Within, like, a month, he had gotten a donor to give $50,000 to run the program," said Harvey. "Now we're creating ways for these students to stay in Vermont."

Kerrick Johnson is similarly impressed with Dombrowski, calling him "the most entrepreneurial person I've met at UVM, ever." Johnson is the chief innovation officer for the Vermont Electric Power Company, known colloquially as VELCO, which runs the state's electricity transmission system. VELCO is also one of the 15 members of Dombrowski's new Vermont Clean Energy and Resilience Consortium. The group, which is composed of several electric utilities and tech companies, wants to collaborate to get some of the $1 trillion in the infrastructure bill that is currently stalled in Congress.

The plan, along with President Joe Biden's $3.5 trillion Build Back Better proposal, would expand high-speed internet access, upgrade power grids and offer rebates for electric vehicles. Experts estimate that, together, the measures would eliminate up to a billion tons of carbon pollution, the equivalent of taking 250 million cars off the road forever.

The Vermont consortium's goal is to "import dollars that help us advance the energy vision we already have," Johnson said. This could include expanding Vermont's electric vehicle charging stations or investing in public transit.

Johnson said he was impressed that Dombrowski cold-called leaders of Vermont utility companies, some of whom he'd never met, to get them involved.

Dombrowski says the energy project is one way to make UVM more accessible and not simply the "university on the hill." At first, he found that business leaders doubted him because they'd found UVM unreliable and unresponsive in the past. People who work at the school questioned whether the university could become a premier research institution without sacrificing instruction.

Eighteen months in, Dombrowski says his doubters are coming around. Faculty see that investing in research creates academic opportunities outside the traditional classroom. CEOs are noticing that Dombrowski shows up and delivers on his promises.

For Dombrowski, the job boils down to making higher education more relevant to more people — a challenge he says he's prepared to tackle.

"We'll just have to keep demonstrating that we are committed," he said, "and then demonstrate it again."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.