- Ken Picard

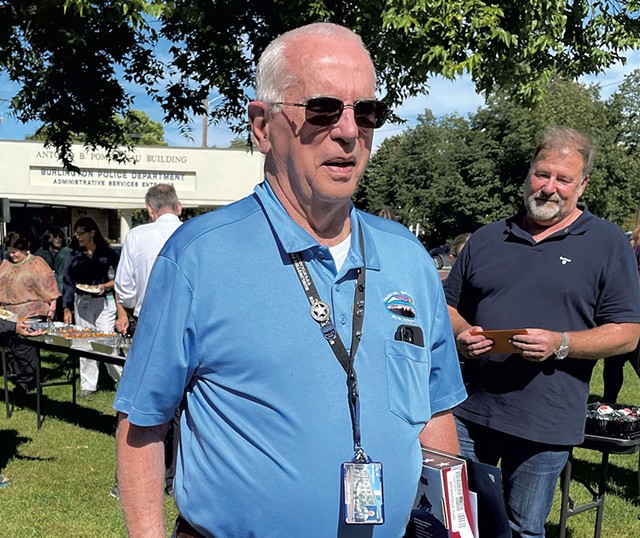

- John King at his retirement party

When John King joined the Burlington Police Department in July 1965, he received just five days of law enforcement training. It included one day to memorize a map of Burlington, another to learn city ordinances and a third to study state criminal statutes. His paycheck for the first week: $62.

By week two, King was handed the keys to a police cruiser and sent on solo patrol, with strict instructions never to leave Burlington while on duty; his municipal authority ended at the city limits. He wasn't even allowed to stop a burglary in progress in South Burlington, which he watched from across the street in Burlington, King recalled.

Much has changed in police training and jurisdiction since then, but fellow cops have consistently held King in high regard. At a time when officer morale is low, recruitment is flagging, and some Burlington residents, including members of city council, want to defund the police and exert tighter civilian oversight, King's recent retirement party provided a rare opportunity for the men and women in blue to celebrate one of their own.

On the afternoon of September 24, civic leaders and members of the police department gathered in Battery Park to mark the end of King's 56-year career. The 77-year-old Waterbury native stood quietly in plain clothes before a crowd of about three dozen, all there to honor his decades of service.

Vermont Public Safety Commissioner Mike Schirling noted that King actually had two police department careers: one as a police officer, which he left as commander — a rank now called deputy chief — and a second, starting in 1991, as parking enforcement manager. Schirling, who retired from the Burlington Police Department in 2015 as chief, called King "the epitome of service, dedication and perseverance."

Burlington's acting police chief, Jon Murad, shared highlights from King's time on the force, including the 1973 arrest of international fugitive L. Wayne Carlson, a notorious Canadian bank robber and jail breaker. Carlson had been stopped and taken into custody at the U.S.-Canada border, Murad explained, and brought to what was then the Burlington Correctional Center. He used a smuggled .38 Smith & Wesson to take seven sheriffs and five prisoners captive and make his escape.

"John found him several days later and made the pinch," Murad said, for which King was awarded Patrolman of the Year.

At the ceremony, Murad gave King a plaque of the police department shoulder patch — made out of Lego pieces. King, a Lego enthusiast, had discovered a few years ago that Murad's wife, Vonnie, is also a fan and had given her some of his sets. In appreciation, she crafted him the BPD logo.

- Ken Picard

- John King holding the Lego plaque

John Tracy, aide to Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.), presented King with a letter from the senator and a flag that had flown over the U.S. Capitol. Tracy said King is the last retiring Burlington police officer to have worked with Leahy when he was still Chittenden County state's attorney.

Burlington attorney Joe McNeil, who also spoke at the ceremony, has known King the longest of anyone in the city. McNeil and King attended Camp Holy Cross in Colchester together when they were kids and have been friends ever since.

McNeil, who served as Burlington city attorney for nearly 38 years, recounted a story about King that he said exemplified his friend's reputation as a man of principles. One day in the 1980s when Bernie Sanders was mayor, someone parked in his reserved spot on Main Street, forcing Sanders to park elsewhere. As a result, McNeil said, Sanders' "old beater of a car" racked up three or four parking tickets.

Fuming, Sanders told McNeil to void the tickets, a decision that McNeil and King normally made together. This time, however, McNeil took the action unilaterally. Later, King gave McNeil an earful for his breach of protocol.

"[King] understood that parking administration can quickly go off the rails," McNeil said. Anytime you dismiss a ticket, he added, "you run the risk of being accused of favoritism."

King's career spanned more than a third of BPD's 156-year history. An amiable man of few words, King was the only member of his family to enter law enforcement. His father was a granite shed worker in Barre; his mother, a stay-at-home mom.

After graduating from high school on a Friday in May 1962, King left for the Army on the following Monday. Though he had expected to serve in Vietnam, after the Bay of Pigs invasion his military police company was deployed to the Panama Canal, where he spent the next three years.

Upon his return to Vermont in 1965, King heard on the radio that the Burlington police were hiring. He applied and started work the following week.

In 1965, Vermont had no training academy for municipal cops, King said. According to the Vermont Criminal Justice Council, the first basic training course for any of the state's law enforcement personnel was held in 1968, in a building previously used as a sanitarium for tuberculosis patients. At first, only state troopers attended.

When town and city police cadets finally were admitted to the academy, state police instructors taught all the courses. This created tension, King recalled, because municipal cops perceived that state cops were running the show.

To alleviate such concerns, the academy asked municipal police to serve as instructors. In the first co-taught class, King joined a state police lieutenant to educate cadets on accident scene investigation. Several years later, when police radar came into widespread use, King was one of two instructors sent to New York State to learn how to train other officers in their use.

City policing was quite different then than it is today. In the 1960s and '70s, most patrols were done on foot, King said, and there were call boxes on virtually every corner that officers used to communicate with dispatchers.

"You had to flip the lever every half hour to let the station know you were OK," he recalled. "There was a red light on top, and if you saw that red light on, it meant the station wanted you."

In some respects, policing was also more laid-back. King remembers when the city jail was located on the corner of Main Street and South Winooski Avenue, adjacent to the fire station, where a public parking lot now sits.

"There were times when you'd arrest somebody and tell them to walk over to jail, and you'd meet them there later," he said. "And you'd go over there, and they'd be sitting on the steps waiting for you."

During night shifts, King carried a key ring to let himself into any business in downtown. Sometimes he'd go on duty at midnight and be in the only car on the road. It wasn't unusual, he said, to work two or three consecutive nights without a single call.

"I don't think people had the tendency to call the police as often as they do today," he said.

But King also had his share of frequent flyers. He recalled one elderly woman living alone in the South End who periodically called the police to report a stranger in her yard.

"So we'd go down and talk to her," King said. "All she really wanted was for you to come in, and she'd have warm chocolate chip cookies and a glass of milk for you."

Parking enforcement was also very different back then. In the '70s, if someone had unpaid parking tickets, the city didn't impound their vehicle, as it does today.

"We arrested the driver and took them over to jail," King said. "And that person stayed in jail ... overnight and was arraigned the next morning."

And because parking tickets were considered a criminal offense, appealing one was a risky proposition.

"I had to explain to the person that ... if you lost, you would get a criminal conviction on your record for the rest of your life," King explained. Schoolteachers, postal workers and even fellow cops rarely appealed for fear of losing their jobs. By the late 1970s, King had successfully lobbied the legislature to make parking tickets a civil offense.

When King became parking enforcement manager in 1991, he heard his share of excuses from people trying to get out of paying tickets, he said. Some were legitimate; others, ridiculous. Usually, King held firm and wasn't swayed by sob stories.

There were some notable exceptions, though. One morning King got a call from a man who was staying at the Radisson Hotel — now a Hilton — on Battery Street. The man had parked on College Street the night before and woken to find his car missing. After an overnight snowstorm, the vehicle had been towed because it was blocking snowplows.

As the man explained to King, he was visiting Vermont from Hawaii for a meeting at IBM in Essex Junction. He had never seen snow before in his life and called his wife to tell her how beautiful it looked.

"He said, 'I just never conceived that you would have to plow it to clean the streets,'" King recalled. So King voided the ticket, but the man still had to pay the towing charge.

Looking back, King is thankful he never had to fire his gun in the line of duty as a policeman.

"I enjoyed my work," he said. "I enjoyed driving to work in the morning, and I enjoyed driving home in the afternoon. If anything, I hope people remember that I tried to treat them equally, fairly and uniformly."

Correction, October 18, 2021: An earlier version of this story misidentified Burlington acting police chief Jon Murad's wife. Her name is Vonnie Murad.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.