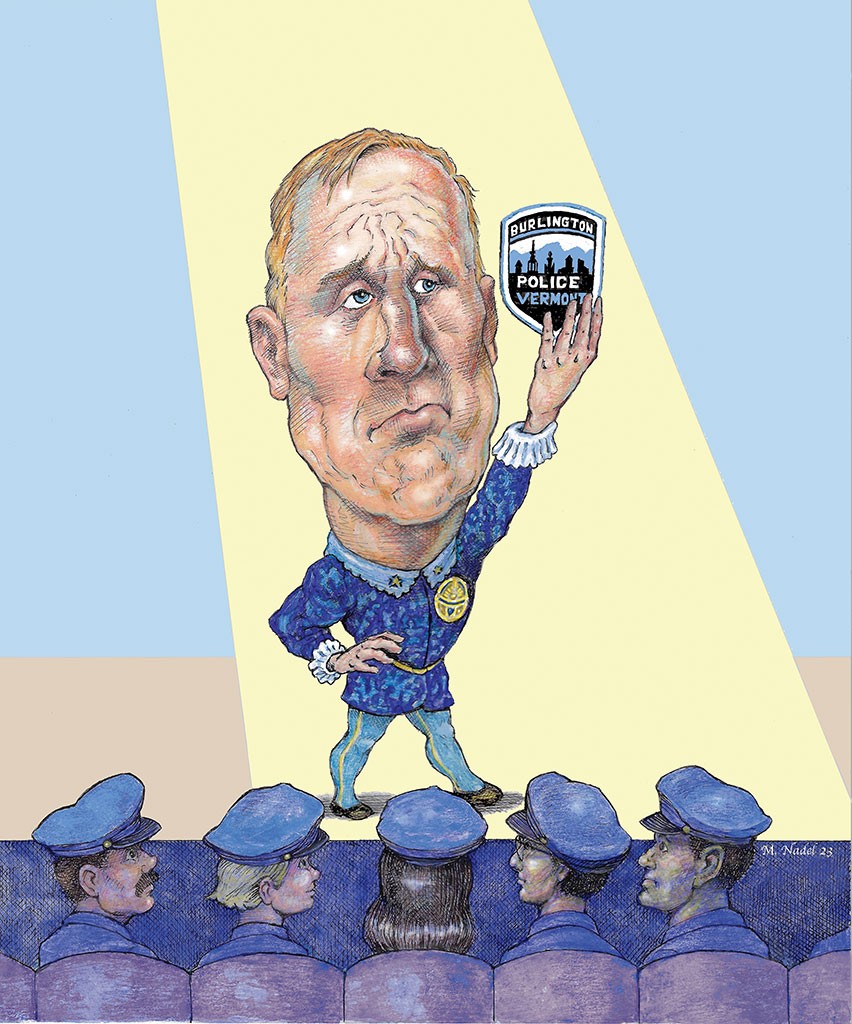

- Marc Nadel

But Murad's converts did not include all members of the Burlington City Council, who, soon after Weinberger's pitch, refused to give him the permanent job on a 6-6 vote. The mayor declined to reopen a nationwide search and said Murad would remain acting chief indefinitely — an arrangement deemed legal by a city attorney and that takes the decision out of the council's hands. More than a year later, Murad remains the acting chief, while Weinberger waits for the right political moment to nominate him again to be the permanent one.

On paper, Murad would seem to have too-good-to-be-true qualifications to be Burlington's top cop. A local boy who grew up in Underhill, he's a Harvard University grad twice over who learned law enforcement as a beat cop and in the executive offices of the New York Police Department.

Once an aspiring actor who spent more than half a decade in Los Angeles, he's a practiced communicator who appears as comfortable in front of a television camera as he does commanding a crime scene. He can rattle off statistics with the intensity of a preacher delivering a Sunday sermon.

Murad has earned the trust of his once-skeptical officers at least in part through leading by example. When the city experienced an unprecedented spate of gunfire incidents in 2021 and 2022, he showed up at nearly every scene — on Saturday, too, after a midday shooting at a downtown apartment. He has signed up for overnight shifts on the beat and worked on Thanksgiving and Christmas.

"He loves Burlington and the people in it," said Michele Asch, a former chair of the Burlington Police Commission. "He's just committed to the work that he's doing."

But in times of crisis, even textbook qualifications may not win a police chief sufficient political support — and Murad has led the department in historically challenging times. He assumed the post in June 2020, during the early months of the pandemic and just after George Floyd's murder by Minneapolis police sparked a global movement against police brutality and racial bias. In Burlington, Murad's officers were already facing excessive-force lawsuits from several Black residents. Just weeks after Murad became acting chief, the city council voted to cut police staffing by nearly a third through attrition. Within a year, more than a dozen cops had left the demoralized department.

Murad and his officers have found themselves under close, often critical scrutiny. Residents and some city councilors have objected to the way Murad deployed his reduced force and, earlier this year, deplored the fact that off-duty officers were providing private security at a condo complex. Last summer, a trauma surgeon accused Murad of threatening to arrest him as he treated a gunshot victim at the hospital.

Murad's critics describe him as ill-suited for the job. They've questioned his temperament, leadership and commitment to reform in a department in which an outside consultant found serious deficiencies. Some of his fiercest detractors serve on the city's police commission, which has expanded its oversight powers in recent years.

"At what point does the mayor take leadership here and rise above this political fight and say this is not working for the city?" said Councilor Joe Magee (P-Ward 3), who wants Weinberger to reopen a search for a new permanent chief. "I think we're long past that time."

During two recent interviews with Seven Days, including a 90-minute sit-down last week, Murad spoke confidently about his leadership and his record of rebuilding the depleted department. Throughout the conversations, he made clear that he'll continue doing the work, regardless of the political distractions.

"My confirmation is not relevant to me," Murad said. "I have the job."

Act One: 'More Than the Norm'

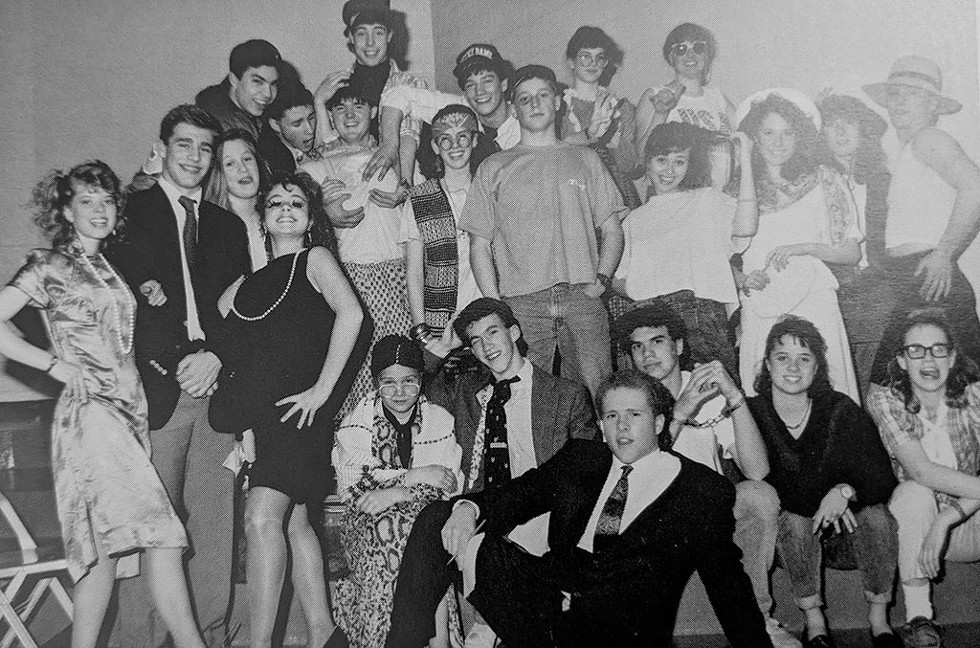

- Courtesy

- Murad (front, seated) in a Mount Mansfield Union High School yearbook photo

Even as a child, Murad seemed to find the spotlight. He was a middle schooler in 1985 when he joined Lyric Theatre's production of Oliver! as the Artful Dodger, a charismatic pickpocket and child gang leader. A Burlington Free Press reporter who attended a rehearsal that fall asked 12-year-old "Jonathan" how it felt to look out from the stage for the first time.

"It doesn't scare me," he said. "Facing the audience sort of feeds my energy."

Murad grew up in Underhill, the eldest son of two University of Vermont professors. In an interview, Tim Murad described his son as having an encyclopedic brain and the ability to quote Shakespeare chapter and verse. The elder Murad remembered how his son had once auditioned for a play at UVM but didn't tell the casting directors he was only in high school until he got the part. They let him keep it.

"To me, it's an indication that he was always striving to do more than the norm," Tim Murad said.

Young Murad stood out at Mount Mansfield Union High School. He was a member of the National Honor Society, won a writing competition sponsored by UVM three times and was part of the school's Scholar's Bowl team when it won the 1991 state championship. His classmates voted him "Best Actor" and "Class Storyteller."

At Harvard, Murad studied English and American literature and kept acting. He was a member of Hasty Pudding Theatricals, one of the oldest theater societies in the world, whose famous alumni include renowned actor Jack Lemmon and the 32nd U.S. president, Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

After graduation, Murad went to Los Angeles in hopes of becoming an actor. Using the moniker "J.C. Murad," he landed a handful of bit parts in shows such as "Beverly Hills 90210" and "Melrose Place." He played a cop nearly every time — an irony not lost on the Rake Vermont, a leftist online outlet in Burlington that panned each and every one of his performances in a January 2022 article.

Murad's last acting credit was a 2001 role in "The X-Files." After the 9/11 attacks that year, Murad said he asked himself what he was contributing to society by chasing a Hollywood dream. "The answer that I came up with was 'Not much,'" he told Seven Days.

He moved to New York City in 2003 to reunite with his college girlfriend, Vonnie, whom he'd later marry, landing at Newsweek as an editorial assistant. But he still felt unfulfilled and took the civil service test to become a police officer. At age 32, Murad started an entirely new career.

Act Two: A Big Leap

- Courtney Lamdin ©️ Seven Days

- Murad at the scene of a shooting in Burlington on Saturday

Murad began policing as a beat cop in 2005, patrolling public housing projects in the Bronx. His résumé indicates that he was a plainclothes field intelligence officer focused on drug interdiction. He soon caught the attention of then-NYPD commissioner Ray Kelly, who assigned him to the Office of Management Analysis and Planning — the so-called think tank of the NYPD.

In 2013, Murad earned a master's of public administration from Harvard's John F. Kennedy School of Government. He gave the graduate student address with his trademark confidence.

"Everyone changes the world," he told his classmates, as Oprah Winfrey, an honorary degree recipient that year, sat just to his right. "It's how we do it that counts."

Around the same time, he started working as a technical consultant for "Brooklyn Nine-Nine," a TV comedy about a fictional New York City police precinct.

In 2014, Murad got a six-rank promotion to become an assistant commissioner at the NYPD under Bill Bratton, a legend in policing circles. In a recent interview with Seven Days, Bratton said he'd spotted Murad's talents when reading a white paper written by Murad and two other officers that examined the department's challenges and how to address them.

Murad had a way with words, Bratton said, and he was smart.

"He's a living Google machine," Bratton said, then laughed as he recalled another of Murad's quirks.

"He uses the craziest expressions in the absence of swear words. I've heard him use the term 'Golly gee,'" Bratton said. "There's this boy-next-door wonder about him."

Murad became Bratton's speechwriter and helped create a new communications office. Notably, his star was rising in a department — and an occupation — under fire. Earlier that year, an NYPD officer had killed Eric Garner, a Black man, by placing him in a choke hold. Michael Brown's death in Ferguson, Mo., a month later sparked Black Lives Matter protests nationwide.

One of Murad's vocal critics, Burlington City Councilor Melo Grant (P-Central District), who is Black and grew up in New York City, said she's disturbed by the acting chief's connection to Bratton. The former NYPD commissioner embraced the controversial "broken windows" theory that calls for policing lower-level infractions, such as vandalism, to prevent more serious crime. Critics say that approach leads to over-policing communities of color.

Murad said he believes "broken windows" is an effective policy.

"Stopping small things before they get big is a key, logical component of prevention," Murad wrote in an email to Seven Days. "I believe that police exist to keep people safe, by preventing and responding to crime and disorder, with and for our neighbors."

Bratton left the NYPD in late 2016 to join Teneo, a public relations firm. Murad followed soon after to work as his chief of staff.

But he missed policing, he said, and home. In 2018, he applied for a deputy chief job in Burlington, where his former NYPD colleague, Brandon del Pozo, was top cop. He got the position, took a 60 percent pay cut and moved back to Vermont.

Act Three: Crisis Chief

- File: James Buck

- Murad at a protest in 2020

In Burlington, Murad found a department that was skeptical of him. Like del Pozo, he was an Ivy League-educated NYPD alum. He had little experience working a beat and was chosen over several internal candidates to be deputy chief of operations. Members of the Burlington Police Officers' Association went to Mayor Weinberger with their concerns, to no avail.

They repeated those concerns a year later, when del Pozo and another deputy chief, Jan Wright, resigned amid a social media scandal, leaving Murad as the logical internal candidate. Weinberger brought in an interim chief, but when she left six months later, Murad became acting chief.

Meanwhile, police officers who were once suspicious of Murad now see him as their defender against a hostile city council. They backed him when the city's search for a permanent chief yielded just Murad and an unnamed person; so did Weinberger. Attempts to reopen the search, led by Progressive councilors who voted against Murad's appointment, have gone nowhere.

When the police ranks were diminished by departures, Murad showed up for the cops who stayed behind. He fought for a new union contract that gave officers sizable raises and retention bonuses, which also supported his plan to staff up. He has gone to their hospital beds when they were injured on the job and to funerals for their loved ones. He worked shifts on the beat and helped at crime scenes, including at last weekend's downtown shooting.

As a chilly rain fell on Saturday, Murad consulted with officers who were collecting evidence outside Manhattan Pizza & Pub. He spoke with pedestrians who asked him what was going on. "There was a shooting," Murad told one curious bystander, who nodded and said, "Things are going downhill."

Weinberger said Murad's tendency to "lead from the front" helped repair his relationship with the rank and file.

"He knew he was in a fragile position with them, and he worked to turn it around," Weinberger said. "I see that as a very positive evolution."

After Weinberger announced his plans to make Murad's job a permanent one in January 2022, the acting chief returned to police headquarters to find his officers had planned their own coronation ceremony: They presented him with two new stars for his uniform collar and a chief's badge. For Murad, it was indicative of how far he'd come.

"That was a very big moment," he said, "to have earned it from them in that way."

When the council rejected Murad's nomination four days later, Murad reassured his troops in an email with the subject line "The Obstacle is the Way." It was a musing on a quotation from Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius that calls for stoicism in the face of a challenge.

"What good old Marcus meant was essentially ... a fancy way of saying when life gives you lemons, make lemonade," Murad wrote in the email, which he shared with Seven Days. "I am still here today. So are all of you."

Murad has continued to go to bat for his officers by resisting an effort to increase civilian oversight. He lobbied against a March ballot measure that would have created a new "community control board" with the power to discipline police, saying it would harm recruitment efforts and strip existing officers of due process rights. Voters rejected the measure by nearly a two-thirds margin.

Murad said the city's current oversight model — in which a civilian-led commission can recommend discipline, but only he can impose it — is "pretty darn close" to perfect. The stance has strained his relationship with members of the Burlington Police Commission, who have been pushing for more oversight power. Last year, three commissioners urged the council to reject his nomination for permanent chief, though two of them refused to discuss the issue when contacted recently by Seven Days. The other, Grant, resigned from the body after she was elected to the city council in March.

Councilor Ben Traverse (D-Ward 5) acknowledged that Murad's "laser focus" on restaffing has turned some people off.

"He has been very defensive at times and protective of [officers]," Traverse said. "Where that has not always served his best interest as being a potential candidate for permanent chief, I do think it's served the best interest of the department."

Members of the Burlington police union declined to be interviewed by Seven Days but did respond to emailed questions. They described Murad as a tireless advocate for them, even as city council Progressives vilified and diminished the department. The union praised the acting chief for creating a "public safety continuity plan" that added community service liaisons — who are akin to social workers — to the ranks.

"No one else was presenting tangible responses to a rapidly deteriorating public safety crisis," the union wrote. "Chief Murad has proven himself as a competent and committed leader during incredibly adverse conditions for any Chief."

He did so, the union said, by "demonstrating political savvy."

Act Four: On Message

- File: Luke Awtry

- From left: Former deputy chief Jan Wright, Mayor Miro Weinberger and then-deputy chief Jon Murad in 2019

Murad worked behind the scenes in the Big Apple, but in Burlington, he's taken center stage.

He uses the spotlight to keep his officers' concerns in the forefront, a tactic that was particularly effective when the city's tally of gunfire incidents increased dramatically in 2021 and 2022. The department has always sent out press releases, but with Murad at the helm, the communications became more regular and included suspects' rap sheets. The procession of press releases didn't merely report the facts — it reminded the public that the department was short-staffed and that officers were sometimes overwhelmed with calls.

TV news outlets ate it up. Burlington crime reports and mug shots made the evening news. So did Murad, who carved out time to do standups for those reports. When the camera turned on, Murad would smoothly launch into his talking points without stumbling. His constant refrain: Burlington needs more cops to battle the surge in crime.

Murad has been less forthcoming with Seven Days. After repeated requests, he reluctantly agreed to be interviewed for this story.

The former actor certainly understands the power of public messaging. The American Civil Liberties Union of Vermont has been critical of what it describes as Murad's inflammatory rhetoric about crime in the city. In summer 2021, the nonprofit advocacy group accused Murad and Weinberger of tying the city's uptick in gunfire to the council's police-cutting vote, charging that the officials' "campaign of misinformation" wasn't borne out by data. At the time, overall calls for service had dropped by nearly half since 2016. Violent crime had decreased sharply, the ACLU said.

Members of the police commission have also challenged Murad's interpretation of data. The body has zeroed in on racial disparities in officers' use of force and has asked Murad to investigate whether bias could be at play. After reviewing body camera footage, some commissioners suspect it is, according to cochair Stephanie Seguino.

"We are observing situations in which, in particular, African Americans, we believe, are treated differently than a similarly situated white person," she said.

Murad disagrees and has said the BPD has "drastically reduced" disparities. He said he's been transparent about use-of-force trends, which he shares with the commission in a monthly report. City staff produce an annual report that breaks down data by race.

The department has also recently begun posting online body cam footage from incidents involving use of force. Murad said members of the public can view the clips and judge for themselves.

The disagreements over alleged racial bias were exacerbated by a TV interview in May 2022 during which Murad described the perpetrators of gun violence as members of an "affinity group," a term that refers to people with a common purpose. The TV station paired Murad's comments with footage of young Black men at a shooting scene. Vermont legislators from the Statehouse's Social Equity Caucus later published an op-ed on VTDigger.org that accused Murad of spreading a "dangerous message."

"Murad's statements use coded speech to garner support from white people by drawing on conscious and unconscious racial-based fears that Black people are violent," wrote the group that included Rep. Tiffany Bluemle (D-Burlington). "This can frighten both white and Black people about crime, lead to more aggressive police activity, and more police racial profiling."

Councilor Grant, a former police commissioner, agreed.

"On one hand, he understands the power of his words," she said, "and on the other hand, he doesn't."

Act Five: Man With a Plan?

- File: Bear Cieri

- City Councilor Ali Dieng

On the wall next to Murad's desk at police headquarters on Burlington's North Avenue hangs a bright yellow sign with the word "Believe" in blue capital letters.

The poster is a replica of one that appears in "Ted Lasso," the hit Apple TV+ show about an American football coach who is hired to lead a struggling English soccer club. Lasso, the central character, is ridiculed for his ignorance about the sport but eventually wins over the team and its fan base with optimism and compassion. In the show, the "Believe" sign hangs in the locker room, an enduring reminder to stay positive.

Murad isn't much like Lasso — he doesn't have a charming Kansas accent, for one thing — but there are parallels in their stories. Like Lasso, Murad is leading a team out of crisis, and by many measures, he's succeeding. But he still has to convince some that he belongs.

Murad acknowledged that the past three years have been trying but said he's settled into the job and the community. He and his wife, Vonnie, live in Burlington's New North End with their two school-age kids, MacArthur and Cady Elizabeth.

Sitting at a conference table during an interview in his office last week, Murad used a personal anecdote to illustrate his view of public safety as a bedrock of society. His wife and daughter had recently finished acting in Lyric Theatre's Shrek: The Musical at the Flynn. Without cops keeping the public safe, "you can't have any of the other things that you want out of a community," Murad said, referring to the play and public events more generally.

To Murad, in this moment, that largely means hiring more cops. Asked about his vision for the future of the department, he defaulted to familiar talking points about immediate staffing needs rather than articulating a long-term plan.

He has made progress toward his goal. Since last September, the city has gone from 51 to 58 "effective" officers, or those who are able to work at any given time. Six others are on leave — such as for military deployments or medical reasons — or are using vacation time before retirement.

Four recruits are expected to graduate from the Vermont Police Academy later this month, and Murad anticipates that more could join the next class in August.

The department is authorized to employ up to 87 officers, a number that aligns with recommendations from CNA, a Virginia-based consultant hired in 2021 to assess police operations. But Murad says Burlington needs between 95 and 100 officers and hopes the city will revisit the number.

Some officers will be deployed to carry out quality-of-life policing downtown this summer. Cops will be conducting more patrols on the Church Street Marketplace and in City Hall Park — where drug and alcohol use have become more apparent — and issuing more tickets for offenses that contribute to a sense of disorder, Murad said.

"We're going to focus on this zone," he said, "and make certain that we're clearly present and that we're establishing a different tone."

Murad acknowledges that his department needs new ways to approach the underlying causes of some crimes. He supports hiring unarmed personnel, including a crisis response team of clinically trained professionals who can respond to mental health and substance-use calls. City councilors have approved of the plan, though some object to housing the team within the police department. It may be several months before it's up and running.

"The more seamless all of that is, the more collaborative it is, the better sewn together it is, the better it will serve the community," Murad said.

Forming a crisis response team was one of 150 recommendations in CNA's report, which was meant to guide future police reforms. But some of Murad's critics say his response to the document has been lukewarm or outright dismissive.

Besides believing that CNA underestimated the number of officers Burlington needs, Murad disagreed with its suggestion that sergeants should regularly audit body camera footage and provide feedback to officers, calling it "an unreasonable" request amid a staffing shortage. Progressive councilors have cited his reaction to the report as a reason they can't support him for permanent chief.

They've also charged that Murad's view of public safety is too myopic. Councilor Magee said Murad isn't vocal enough about addressing the drug crisis at a time when the city's overdose numbers are soaring. By contrast, del Pozo — Murad's predecessor — was an early adopter of harm-reduction strategies.

During last week's interview, Murad acknowledged the issue and pulled out a chart showing overdose rates. The problem seems intractable, he said.

"I don't know what we can do until we're properly resourced, but we can't wait until we're properly resourced to address that," he said.

Councilor Joan Shannon (D-South District) empathizes with Murad's situation. Del Pozo had the luxury of a fully staffed department, she said, which allowed him to work on other priorities.

"I would not want Jon to be focused on anything but keeping our head above water, honestly," she said.

Weinberger has suggested he won't ask the council to formally appoint Murad until he knows he has the necessary seven votes, and it's unclear if he does. Shannon and Councilor Mark Barlow (I-North District) would vote yes, while all four Progressives would say no. Councilor Ben Traverse (D-Ward 5) said he is unsure where he stands. Four other Democrats didn't return interview requests from Seven Days.

Councilor Ali Dieng (I-Ward 7) has gone back and forth. But after the incident in which Murad confronted the surgeon, Dieng decided the acting chief has "too much baggage."

"I am coming to realize Burlington needs a fresh person," he said. "Someone with the ability to rebuild trust."

Many of his supporters wonder why Murad wants this job at all, when he could easily find work somewhere else — and perhaps be better appreciated there. The question came up at a January community meeting about gun violence at AALV, which helps immigrants from Africa settle into life in Vermont. Murad had been invited to the Old North End center by Sandy Baird, an attorney and family friend. Murad's parents were among the handful of people in the audience.

The acting chief acknowledged that the past two years had been exhausting, saying he felt as if he alone was trying to raise the alarm about increased gun violence. Murad then dropped a reference to a character from Oresteia, the Greek drama in which he'd performed during high school. He'd felt like Cassandra, he said, a prophet who foresaw tragedy but was cursed never to be believed.

But then, as so many times before, the acting chief spoke of his love for Vermont, about his wife and two children, and of his commitment to the job.

"I'm here," he said, "and I'm not going anywhere."

Correction, May 3, 2023: A previous version of this story included inaccurate historical crime data.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.