- Courtesy Of The City Of Burlington

- Interior of a "shelter pod"

In December, Burlington razed what was left of the Sears Lane homeless encampment in the South End. Mayor Miro Weinberger had abruptly ordered campers to clear out earlier in the fall, angering activists and Progressive city councilors who had tried to get him to reconsider.

Five months after the controversial decision, Weinberger has made ending homelessness one of his primary objectives.

On Monday, the Burlington City Council approved the mayor's plan to build a low-barrier "shelter pod" community in a parking lot in the Old North End. A resource center there will provide a place to warm up, and staff will connect people with social services. And next month, a new city employee will begin leading programs aimed at ending chronic homelessness, which Weinberger has pledged to do by the end of 2024.

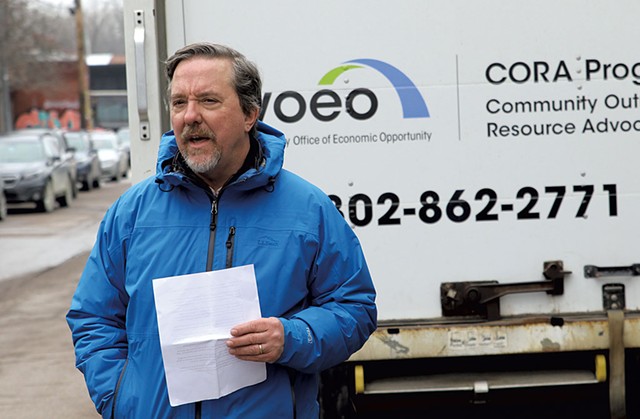

Community nonprofits have also stepped up. Last week, the Champlain Valley Office of Economic Opportunity unveiled a new truck that will enable its outreach team to make daily deliveries of food and other essentials to encampments. Staff expect the vehicle, which has a laptop, a microwave and other amenities, to regularly visit the pod village.

"We can do huge things if we're committed to it, and I think that's what we need to do here," Weinberger told Seven Days last week. "We can't be just looking to incrementally chip away at this."

The efforts are part of a 10-point housing plan Weinberger unveiled late last year, less than a week after the demolition of the Sears Lane encampment. It also includes goals to rezone areas of the city to spur residential development.

Homelessness has been a chronic, and daunting, problem in Burlington as housing prices have risen higher than ever. Some homeless advocates are pleased to see Weinberger act after the debacle at Sears Lane, which occurred just as winter set in. But others say the measures he's proposed are temporary fixes when the city should be investing in long-term housing options.

"This is not a plan to end homelessness in two years," said Brenda Siegel, a political activist and former candidate for lieutenant governor who has advocated for unhoused people. "There's some good stuff in here, but a lot of these are Band-Aids; they're not solutions."

- Courtney Lamdin

- Parking lot at 51 Elmwood Avenue in Burlington

The city has been working to eliminate homelessness for decades, but the recent infusion of federal coronavirus relief funds has reinvigorated the effort. In summer 2020, the city applied for a $1.3 million grant to build tiny homes at Sears Lane, but the Vermont Housing & Conservation Board denied the request. Several campers subsequently built their own shanties, which lacked running water and were powered by generators that irritated neighbors. The encampment was erected without permission on city-owned land.

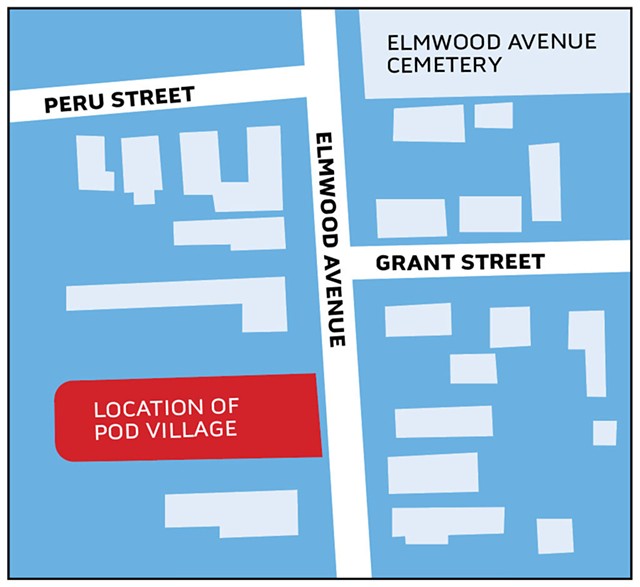

Using $1.47 million in American Rescue Plan Act cash, the city will try to build a better regulated, safer community for people without homes — from the ground up. The council's vote on Monday will put the 30 shelter pods in a city-owned parking lot at 51 Elmwood Avenue, not far from downtown. Ranging in size from 60 to 120 square feet, the pods will have electricity, heat and air conditioning. Residents will share showers and toilets in a modular unit.

The pods will essentially function as tiny apartments, with each "tenant" having an assigned, secure unit of their own for six to eight months. Caseworkers will help people find long-term, stable housing.

The city is searching for a local nonprofit to manage the community, which it hopes to open by July — around the same time the state will end its program that pays for homeless people to live in motels. The pod city will operate for three years.

- Courtney Lamdin ©️ Seven Days

- Brian Pine

"If we're going to prohibit encampments like Sears Lane, we as a city have an obligation to provide an alternative. This is what that's intended to be," said Brian Pine, director of the city's Community & Economic Development Office, which is managing the project. "I have no question there will be plenty of demand and interest for living here."

But the proposal is already controversial. Some speakers at Monday night's council meeting said the pods have no place in a residential neighborhood downtown and expressed concern about a potential increase in crime. Others said the pods will give unhoused folks a leg up out of poverty and a sense of stability that could discourage antisocial behaviors.

City officials considered nine other spots on city-owned land, including Sears Lane, but picked the Elmwood lot because it's close to services that unhoused people may need, including the Feeding Chittenden food shelf on North Winooski Avenue, the state Economic Services Division outpost on Pearl Street and the Howard Center's syringe exchange on Clarke Street.

The village will also have a code of conduct that could make illegal activity an evict-able offense, but Weinberger says he won't support a policy that prevents people with substance-use disorder from living there.

"In some ways, I hope people who are suffering from that kind of challenge find their way to this facility," he said, "and we can help them get greater help from there."

Others question whether the pod plan can adequately meet the demand for temporary housing. Siegel, the homeless advocate, wondered how the city will help the dozens of others who won't get a pod. And she criticized the city for not consulting unhoused folks about whether they'd use the shelters before deciding to build them.

Public Works Commissioner Solveig Overby raised the same issue last week as her commission considered closing the Elmwood Avenue lot so that it could be used for the pods. She ultimately cast the sole "no" vote, though the measure passed.

"[The campers] wanted a community like Sears Lane; that was working. I don't think it was working for other people," she said. "However, we need to be able to integrate them into making decisions about how they want to be housed."

- File: James Buck

- Sarino Macri at Sears Lane

At least one former Sears Lane resident wants a pod. Sarino Macri, who was kicked out of his hand-built tiny home, has already contacted outgoing Council President Max Tracy (P-Ward 2) and CEDO staff. He's been living at a South Burlington motel on the state's dime since the camp was taken apart last fall, and he said he'd like a place with showers and electricity once the motel program ends on June 30. Macri said he'd appreciate living in a community with rules and structure.

"I have no place to go," he said. "It's a big help for me if I can get one."

Unlike Macri, some unhoused people might want to avoid a city-managed facility or neighbors who have already made them feel unwelcome.

Burlington homeless advocate Stephen Marshall said people would be justified in not trusting the city after what happened at Sears Lane. But he still supports the pod village as a way to offer dignity and freedom. He also suggested that the city invest in permanent tiny homes.

The shelters are "a Band-Aid approach, but maybe that's what's needed," Marshall said. "The reality is, a lot of folks need housing, and people I hear talking about it at lunch do not seem negative about it. They're looking forward to what the city's gonna do."

Marshall is also a proponent of allowing people to camp, which is banned by city ordinance in certain places, including public parks. Last month, Councilor Joe Magee (P-Ward 3) proposed decriminalizing camping on all public lands, though it would still be prohibited in some places.

Magee says the ordinance wouldn't sanction camping outright; rather, the city would only remove encampments that pose health, safety or environmental concerns, and campers could appeal the city's decision. His proposal would also stop the city from punishing an entire encampment if only some members caused trouble — a clear response to the mass eviction at Sears Lane, where two people were arrested before the city ordered the camp's closure. A council committee and city attorneys are vetting the proposal.

Weinberger, however, said condoning camping generally works against the goal to end homelessness. The mayor recognized that some people may not want to live in a regulated pod village, but he said camps can create public health and safety issues.

"It represents a very different concept of how we best address this community challenge [of homelessness]," Weinberger said of Magee's approach. "It's essentially suggesting that this can be done through tents and encampments, and I don't see it that way."

Magee supports the pod plan but said his camping proposal could help those who refuse to live under the city's thumb.

"Even as we expand low-barrier shelter options like the pod community, there will be folks who require the no-barrier autonomy that is provided by camping," Magee said. "It's important that we have these protections codified into city law."

Despite the differences of opinion, Weinberger and his critics agree that the best solution is to create more long-term housing. The mayor's plan calls for working with groups such as the Champlain Housing Trust to build 1,250 new homes in the city, 312 of which would be permanently affordable, by 2026. Close to 80 would be designed specifically for formerly unhoused people.

Some of that work has already started, according to Champlain Housing Trust CEO Michael Monte. His organization is working with the Veterans of Foreign Wars to redevelop the group's South Winooski Avenue building into a 30-unit affordable apartment complex. Priority would be given to homeless veterans, who could use a new Veterans Service Center with computer labs and therapeutic spaces on the building's lower levels. The housing trust has requested a $400,000 Community Development Block Grant from the city.

The nonprofit is also negotiating an expansion of its offerings at Cambrian Rise, a sprawling housing complex on North Avenue where it currently runs a 76-unit affordable apartment building called the Laurentide.

Several formerly homeless people live at Laurentide, but it's not a perfect solution. In recent weeks, residents have complained about criminal activity there, prompting the housing trust to relocate at least two people. The trust has also hired a security guard, Monte said.

For now, Weinberger thinks the pod city is a step in the right direction for ending homelessness in three years.

"Not only do I think it's possible, I think it's critical that we believe that we can actually solve problems on a timescale like that," he said. "Having that sense of urgency is what's going to get us there."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.