- Bear Cieri

- Tom Flanagan

On the second day of the school year, Burlington school superintendent Tom Flanagan strode down the halls of C.P. Smith Elementary School, greeting staff and students. It was still morning, but the temperature outside had topped 80 degrees, so Flanagan had shed his suit jacket and rolled up the sleeves of his blue button-down. A 48-year-old former hockey and soccer player, he still has the solid build and buoyant energy of an athlete.

He popped his head into the nurse's office. "Good morning!" he said cheerfully. "How's it going so far? Pulling all the paperwork together?"

"It's going great," school nurse Christine Harris replied.

Out in the corridor, he called to a passing custodian, "Suzy, it's looking great in here!"

In the learning center, librarian Beth Lane stood in front of a group of fourth graders.

"Hey, Mr. Flanagan!" she greeted the superintendent. She explained that the class had just practiced lining up silently in alphabetical order and that the fifth grade purchasing club would be in charge of $800 of the library budget this year.

"What?!" Flanagan said, with exaggerated incredulity, as the masked students gazed up at him.

His green eyes, behind round tortoiseshell frames, scanned the group of students. "How's it going so far? How's day two?" he asked.

"Good," a few called out.

"Well, I'm so excited to be back here with you," Flanagan told the 9- and 10-year-olds, who then went around, sharing their favorite summer reads.

Flanagan's exuberance is just one thing colleagues, parents and community members say they like about the first-time superintendent, who is entering his second year as the school leader in Vermont's largest city. A recent transplant to the Green Mountains, Flanagan was confronted on his arrival in July 2020 with challenges that would have strained even the most experienced administrator.

He took over a district with nearly 4,000 students, more than 1,200 employees, a $91.5 million budget — and a recent history of rocky superintendencies. Flanagan replaced Yaw Obeng, a Canadian and Burlington's first Black superintendent, who first struggled to obtain a work visa and then drew criticism for choosing to live in South Burlington and send his children to school there. Obeng's predecessor, Jeanne Collins, departed after a controversy about financial mismanagement.

As Flanagan arrived, the COVID-19 pandemic was about to force the district into a disruptive mix of remote and in-person learning for the 2020-21 school year. Then, a day before school opened, elevated levels of carcinogenic chemicals were found at Burlington High School. The school system also faced longer-standing challenges — perhaps first among them questions about equity and systemic racism in a district composed of 40 percent students of color.

By all accounts, Flanagan has tackled all these issues with vigor, acting quickly to find a temporary space for the high school when health officials deemed the existing one unsafe; communicating effectively about the pandemic with administrators, teachers and families; and reaching out to communities of color to hear their concerns about the city's schools.

"I've been watching him carefully and with skepticism, to be honest, because the school is a big, heavy system, and there are a lot of things in place that are hard to change," said Emma Kouri, a parent who chaired a school safety task force last year.

Kouri said Flanagan has allayed her concerns. "He leads with compassion. He leads with vulnerability. He leads with curiosity," she said. "I have been very pleasantly surprised."

Burlington School Board Commissioner Martine Gulick said she also initially wondered whether Flanagan was up to the challenge.

But "he seems to be handling the stress of all of this really well," said Gulick, who lives in Flanagan's New North End neighborhood and sees him out and about with his wife and three kids. "I'm just always kind of impressed, and also amazed, at how he seems to stay calm, take care of himself, take care of his family and also meet the needs of the district."

Others say they are reserving judgment for now. Stephanie Seguino, who served on the school board from 2014 to 2018, said that before Flanagan is judged a success, he must demonstrate substantive and measurable progress in better serving the district's students of color. Some benchmarks, according to Seguino: recruiting a more diverse staff and reducing the disproportionately high suspension rates for African American, special education and economically disadvantaged students.

"The data need to tell us," said Seguino, a University of Vermont economics professor. "So, the proof is in the pudding, and we'll see."

To handle the many challenges he faces, Flanagan can draw on his experiences as a high-level administrator in larger cities — Washington, D.C., and Providence, R.I. — although he notes it is a much "different thing when you're the person who's ultimately responsible for the whole thing."

When he's having a hard time with an issue, he said, he always comes back to one question: "What is the right decision for kids?"

During a walk-through at Hunt Middle School on the second day of school, Flanagan came upon a staff member helping a student learn to use her locker.

"How does it feel?" Flanagan asked the girl about the return to school.

"Sad," the student said. She told Flanagan about her long, tiring bike ride to school and her anxiety about returning to the classroom.

"I'm sorry to hear that," Flanagan said, his voice taking on a soft, sympathetic tone. "So, you're working through the first day, kind of getting back into it, huh ... Do you have someone here who can help you if you're feeling nervous?"

The student gave a noncommittal "I don't know," but the staff member assured the superintendent that she did.

"It's really important to have people who can help," Flanagan said before he moved on to another classroom.

A Seat at the Table

- Bear Cieri

- Tom Flanagan asking students about their summer reading while visiting the library at C.P. Smith Elementary School

Flanagan's own experience growing up in Washington, D.C., shaped his desire for more equitable schools. He was raised in Mount Pleasant, a historically African American neighborhood that saw an influx of refugees from El Salvador and Guatemala in the 1970s and '80s.

He played basketball with neighborhood friends at the local school playground. But when it came time for him to start school, his mom entered a lottery so he could attend one with a better reputation in a wealthier neighborhood.

"I was a little kid, so I had no idea what was going on," he said. But he always wondered why he couldn't go to school in the neighborhood where he lived.

"What it led me to want to do is to make sure that schools in neighborhoods across cities, and the programming within schools, is really good for everybody," he said.

Flanagan graduated from the University of Oregon, where he majored in religious studies. During a stint as an assistant soccer coach in college, he discovered how much he enjoyed working with young people.

He moved back to Washington, D.C., in his twenties to be closer to his younger half-siblings and taught at a progressive, independent school before earning master's degrees in educational administration and special education. He was a high school history teacher, then a special education coordinator and principal in D.C. public schools.

"Being a principal ... I worked in some schools where you really had to stay calm, and you really had to make sure that you were always thinking about what's best for kids," Flanagan said of the sometimes chaotic, physically and emotionally draining environments in which he worked.

Flanagan became the D.C. system's deputy chief of specialized instruction, overseeing special education programs in 2012. Four years later, he became chief academic officer of Providence Public Schools in Rhode Island.

The Providence district had developed problems so serious that the state took control in 2019, after a Johns Hopkins University report documented student learning deficits, deteriorating school buildings and inadequate services for English language learners.

Flanagan said he publicly supported the state takeover because it allowed for a reorganization of leadership to happen. He described Providence as a "complicated place" to work, with constant turnover at the administrative level that led to a piecemeal approach to instruction. Systems intended to mitigate the long history of corruption in the city also made it hard for the school district to function effectively.

He worked for three years under former Providence superintendent Chris Maher, who said Flanagan was an effective leader in the troubled district. Flanagan helped restructure departments focused on students with disabilities and those who were learning English. And he led the charge to make sure educators were using high-quality curricula in order to increase the rigor of teaching.

"He has a deep passion to look at inequities and address them," Maher said.

When a job opened up in Burlington, Flanagan found much that appealed to him about the Queen City. He liked the size of the school district compared to the vast systems he'd previously worked in — big enough to feel like a challenge but small enough that he'd be able to get to know all the schools. A lover of food and music — his stepfather founded the famed 9:30 Club in Washington, D.C., and Flanagan has fond childhood memories of seeing punk and new-wave bands there — he appreciated Burlington's lively culture. So did his wife and kids. Because of his experience in Washington and Providence, districts where more than 90 percent of the students identify as people of color, he also felt at home in a place with a diverse student body.

In fact, Flanagan said it was an easy decision for the family to settle in the city and send their daughters — a seventh grader and third-grade twins — to its schools.

The timing of Flanagan's hiring allowed him to get a better feel for the city before starting his new job. He was named Burlington's incoming superintendent in March 2020, the same week that Providence Public Schools closed for in-person instruction because of the pandemic.

The shift to remote classes gave Flanagan the flexibility to embark on a spring listening tour, speaking to Burlington community members on Zoom to learn about their desires for the school district.

"I think the way sustainable change happens is doing work with the community," he said. "There is a lot of good stuff that has been happening here over time, and a lot of committed people, and it's really about building on that foundation."

Liz Curry, who served on the Burlington School Board from 2013 to 2020, agrees that Flanagan is continuing to build on initiatives — including annual equity reports and efforts to hire administrators of color and curtail police in schools — that were already under way. That's important to consider when assessing his tenure thus far, she said.

"Tom is sitting at a table that was set," Curry said. "Perhaps some of the table was out of order, and he's putting it in order."

"We are so lucky to have Tom. We really are," Curry said, citing Flanagan's ability to bring people together and his understanding of systemic racism. "In this moment in history, he is the person we needed, for a lot of different reasons. And one of the reasons is the white power structure feels comfortable with Tom. And if that's what it takes to really make a change, that's what it's going to take."

Listen and Learn

- Bear Cieri

- Tom Flanagan with students on the playground at C.P. Smith Elementary School

Flanagan acknowledges that, as a white man, he might be an imperfect messenger for "erasing and dismantling systems of power and systemic racism," something he says he's committed to doing.

He hopes that his actions speak for themselves.

At the beginning of last school year, he took a middle school teacher's recommendation to expand access to in-person instruction for students learning English and those receiving special education services. Those students were offered four days per week in the classroom during the COVID-19 pandemic, instead of the two prescribed by the district's hybrid model. Though the shift created scheduling challenges, Flanagan said it was worth it because it gave those students the extra support they needed.

Estella Shela, a recent immigrant from Burundi and the mother of four teenagers, agreed. Through a translator, she said she was grateful her kids were able to spend more time in the classroom. Managing to keep them on track with their studies at home would have been difficult, she said. And, as a member of a parent advisory council last school year, Shela said, she felt that Flanagan valued her perspective and demonstrated that he cares about people of color.

City councilor and Burlington parent Ali Dieng, who grew up in Senegal, has had a similar impression of Flanagan. Dieng founded Parent University, a program for New American families, and worked in the school district for 13 years before leaving for a new job this summer.

"He's committed to equity and inclusion, and I think he has demonstrated it beautifully," Dieng said. "He works very well in ... supporting Parent University, supporting the interpreters and supporting New Americans academically."

The first official meeting Flanagan had with community members was with New American parents, Dieng noted.

Some of those parents told Flanagan they felt like their children were being cared for at school but not challenged, the superintendent said. It's something that's stuck with him.

"The big work of social and racial equity is around what teaching and learning looks like," Flanagan said. "How do we make sure that learning is challenging, engaging and empowering for students?"

To that end, he holds monthly meetings with building principals so that they're on the same page about concepts such as systemic racism and unconscious bias. The leaders also look at district data for trends in student outcomes based on race, special education and economic status.

Only 6 percent of teachers in the district identify as Black, Indigenous or people of color. Flanagan said he hopes to use additional strategies to recruit, hire and retain more BIPOC teachers, including alternative pathways to teacher licensure through local universities, as well as updating hiring and recruitment policies.

"We want our students to see representation of themselves in the adults who are working with them," Flanagan said.

Though Burlington has had a diversity and equity coordinator since 1997, Flanagan last year created a formal Office of Equity and equipped it with additional staff and funding. This summer, that office organized a monthlong Racial Justice Academy to teach about social and racial justice and restorative practices, and to give students of color leadership skills so they can work for change.

In 2014, the Burlington School Board attempted to cut armed police officers, known as school resource officers, from schools but ran into opposition from the city. In February, a school safety task force called for the district to eliminate one of the officers and reassign the other to the Burlington Police Department.

The task force cited racial disparities in arrests in city schools and the discomfort and fear that BIPOC students reported due to having officers on campus. Flanagan supported the recommendations and brought them to the school board, which approved them in April.

"He didn't push back," said task force member Kouri. "He totally trusted us and went to the school board with it, and I think that was really brave, because [police in schools is] a very polarizing topic right now."

Flanagan has also acted on feedback he's received directly from students. Some told him they felt that a policy prohibiting hoods from being worn in school affected students of color unfairly. Flanagan did away with the rule this summer.

He also meets monthly with teacher and student advisory panels to listen to their questions and concerns.

"At the beginning, I wondered how much of it was for show," said senior Peter Kuypers, a member of the student group. But "he's done a great job of taking our input and actually doing something with it."

When high schoolers told the superintendent that the food choices in the downtown high school's cafeteria were lacking, Flanagan "took it upon himself to try to get more variety," Kuypers said. A week or two later, there were new pizza and salad options.

Flanagan said he sees connecting with students and teachers as a core part of his job and estimates he's visited at least 90 percent of classrooms in the district.

Because he's regularly in the schools, "he is acting and reacting from a place of understanding who we are and what we're doing and where we need to go, which is positive and productive," said Burlington Education Association president Beth Fialko-Casey, a high school English teacher.

"When I'm stuck in the office for too long, I like my job less," Flanagan said. "I'm really intentional about being in schools because it gives me energy. I think, to be a good superintendent or a good leader, you have to be with the folks who you're leading."

'A Huge Blow'

- File: Luke Awtry

- A sign at Burlington High School in May

When Flanagan became superintendent on July 1, 2020, the pandemic was the only crisis on his radar — and one he said he felt "relatively prepared" to handle. Vermont was doing a better job dealing with COVID-19 than any other state in the country, he said, and there was clear public health guidance about how to mitigate virus risks in schools.

But another calamity was hiding in the air, walls and foundation of Burlington High School: carcinogenic chemicals known as PCBs.

As the district prepared to welcome students to Burlington High School's Institute Road campus last September, Flanagan got some very bad news. Environmental tests done before the district embarked on a $70 million high school renovation project found "alarmingly high" levels of the chemicals in a building used by the tech center. Flanagan decided to close the high school immediately while awaiting additional testing.

Those tests found levels above Vermont's guidelines for PCBs. The district's building consultants, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the Vermont Department of Health all advised Flanagan that the high school was not safe for students. The superintendent ordered the building to be closed indefinitely. Students continued to learn remotely.

Besides being used for sports practices and meal prep in uncontaminated areas, the campus has remained vacant ever since.

"It was a huge blow, a huge impact to the community and a major thing that was happening, but ... I didn't feel like it was a huge decision that we had to really toil over," he said of closing the school.

Flanagan then created a small committee to explore potential sites for a temporary high school. When the search zeroed in on the 150,000-square-foot former Macy's building on Cherry Street in the heart of downtown, Flanagan and his staff hashed out a three-year lease with the owners of the building.

- File: Cat Cutillo

- Burlington High School

He also requested a face-to-face meeting with Gov. Phil Scott to ask for state support. Scott didn't make any promises, Flanagan said, but he ultimately came through with $3.5 million for construction costs.

The district set a tight timeline for the renovations. And on March 2, 10 weeks after the lease was signed, Flanagan stepped up to a podium and welcomed staff, students and community members to their temporary high school. He was met with a chorus of claps and cheers.

"It's amazing to think that we are standing in what used to be a department store, that we're greeting people where we used to buy winter coats, reading books where they once sold fine china, taking phone calls in converted changing rooms and learning science near the old suit racks," he said.

Megan Munson-Warnken, a longtime parent in the district, said she was impressed with the quick turnaround. "I do not believe anyone else would have gotten us into Macy's so quickly. That was stunning," she said. "And, honestly, I didn't believe we could, and I was so pleased and humbled to be proven wrong."

The transition hasn't been totally smooth.

Last year, parents and students complained about harsh lighting, the lack of windows and high noise levels in rooms where the walls don't reach the ceiling. The district worked to fix problems, replacing bright light bulbs with softer ones and extending the walls.

On a recent walk-through of the space during the first week of school, one teacher pulled this reporter aside to voice concerns about the noisiness in some classrooms.

"He's not wrong," Flanagan said, when told of the teacher's comments. The superintendent said the district is still making tweaks as students and staff settle in for what could be a long stay.

At the very least, the stay is indefinite. After additional testing found more widespread PCB contamination on the Institute Road campus, Flanagan urged the school board in May to abandon the high school renovation and construct a brand-new building.

The board accepted his recommendation in a unanimous vote.

"It would have been easy for the district to be bogged down in months of indecision," said Burlington Mayor Miro Weinberger, who praised Flanagan for acting decisively during a challenging time.

School Commissioner Gulick said she saw Flanagan's strong leadership in the way he approached the decision to cut bait on the old building.

"I know a lot of us were very hesitant to do that after all the work we put in," Gulick said. "I remember at one meeting he said, 'You know, this is the time for us to lead. And there are gonna be some hard things that we have to do, and this is one of them.' That was important to hear. It was motivating. And just to feel like we have this unifying message coming from our leader ... it was really empowering."

The school board is now considering several sites for a new building, which it would like to have up and running by August 2025.

"We know that's a really aggressive timeline. I don't want to minimize it," Flanagan said. "But I'm starting to feel like I'm seeing a path."

A Five-Year Plan

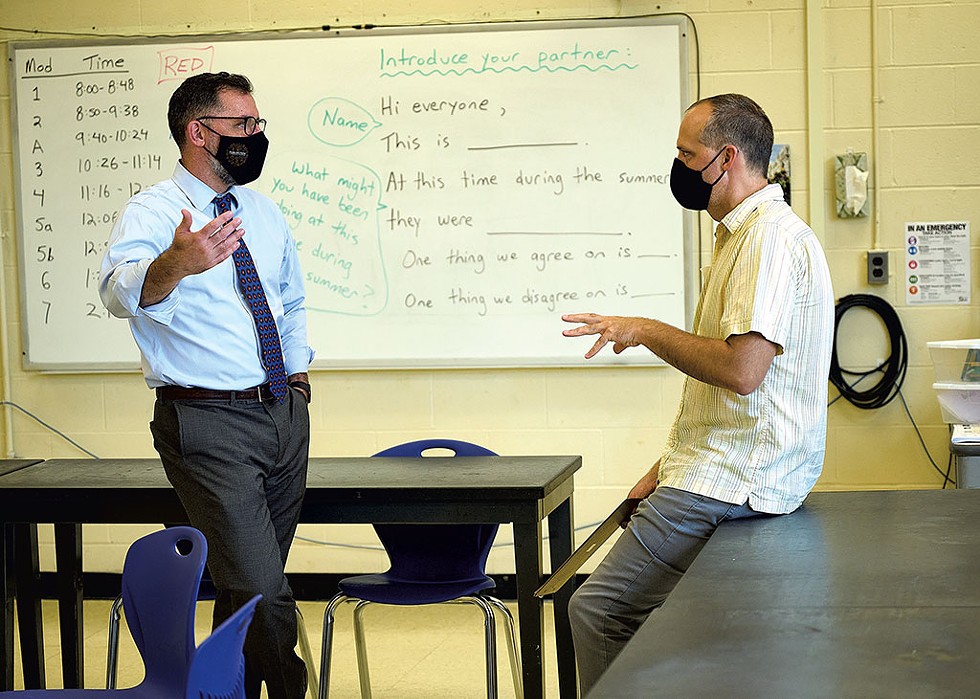

- Bear Cieri

- Tom Flanagan (left) talking with science teacher Nathan Caswell during a tour of Hunt Middle School

An effective superintendent must troubleshoot day-to-day issues while also developing a long-term vision for schools.

Edmunds Elementary School principal Bonnie Johnson-Aten, who served as the school district's first diversity and equity director from 1997 to 2000, describes Flanagan as skilled at both jobs. None of the curveballs thrown his way "became an excuse not to do the real work," she said.

With the transition back to in-person learning going relatively smoothly this month, Flanagan has begun work on a new five-year strategic plan for the district with the help of the Burlington community. It will address big-picture issues such as increasing academic rigor, creating more equitable schools, and preparing students for careers and college.

A diverse group of 50 parents, students and employees will work this fall to collect stories and information about community members' experiences in the district. The coalition could present its findings to the school board as soon as November.

Flanagan said he's committed to seeing the plan through all five years — or longer. In other words, he said, he plans to stick around for a while.

One issue he is tackling right away is what he describes as the "inequitable" way in which Vermont allocates state aid to education. Flanagan is part of a coalition of diverse school districts across Vermont pressing legislators for changes that would provide more state assistance to schools with a large number of students whose education costs more — for example, English language learners and those who live in poverty.

If the state aid formula were to be revamped to provide his district with more funds, Flanagan said, Burlington could better serve its students and hold down property taxes. And that could help counteract the tax increase Burlingtonians will likely face for the new high school.

Whether the school will be built on the existing New North End campus, which would require approximately $20 million just to remediate the chemicals, or somewhere else remains to be seen; there's lots of work ahead.

"Here we are, the biggest city in the state, the economic driver for Chittenden County and, long-term, we don't have a high school," School Commissioner Gulick said. "I mean, that's just very disturbing and very troubling."

Flanagan said he's heard from a number of community members who want the school to rebuild in the New North End, while others are excited by the idea of having a permanent downtown high school.

Count Mayor Weinberger in the latter camp: He spoke favorably of using the city's Gateway Block — which includes Memorial Auditorium, a city-owned parking lot and several private properties — on Main Street.

Whatever location prevails, Flanagan will have the heavy lift of selling the nine-figure project to the city's voters.

Burlington residents have approved the school budget for seven years straight, most recently with support from more than 75 percent of voters. In November 2018, residents approved a $70 million bond for a high school renovation, which the district is now in the process of returning — though $4 million has already been spent.

In March or November of next year, voters will be asked to approve a bigger bond. Flanagan said he's hoping to find additional state and federal support for the high school project to ease the burden on Burlington taxpayers, many of whom were just hit with a tax hike from the city's recent property reassessment.

And though Flanagan said the high school project is his greatest technical challenge this coming year, he sees several bigger-picture ones: making sure that students are engaged in learning and continuing his work to build trust and relationships with members of the school community through listening, and responding, to their needs.

Leaving Hunt Middle School on the second day of school, Flanagan happened upon a New American student and his family having a meeting with school staff and a multilingual liaison in a small stone courtyard.

"Hello, how are we doing?" Flanagan asked, approaching the group. The superintendent pulled down his mask, revealing his smile and trim salt-and-pepper beard to the seventh grader.

"This is me with no mask on, so you remember," he told the student. "How's school for you? Tell me honestly. I want the full truth."

The student returned the smile but didn't answer.

"I'll come back," Flanagan told him. "We can talk, OK?"

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.