- Bear Cieri

- Shoreham Inn and Pub

On a quiet Sunday evening at the Shoreham Inn and Pub, a pair of women chatted over glasses of wine at the bar. Nearby, a solo guest ordered the burger-and-beer special. The small crowd was mostly locals, co-owner Andrew Done said later.

Tucked into a front corner table sat Judy and Will Stevens, owners of Golden Russet Farm & Greenhouses, located about four miles from the inn. When the couple first moved to Shoreham in 1984, recalled Judy Stevens, the historic white clapboard-sided building with its "circa 1790" sign operated as a bed-and-breakfast and offered no regular public meals.

In 2005, Molly and Dominic Francis bought the Shoreham Inn and added a country-style pub, which grew into a community hub over their 14-year tenure. The current owners, Done and his wife, Elizabeth, continue that community focus.

Over the years, the casual restaurant has hosted numerous town fundraisers and special events as well as regular meet-ups for various groups, Stevens recounted. Tennis players can head to its outdoor deck after weekly matches on the town courts; other locals gather in a cozy corner over a shared passion for rug hooking.

Seven Spots

For the town of about 1,200 residents, the venue just off Route 22A is a comfortable spot close to home where neighbors can connect over food and drink. Like many such destinations in small-town Vermont, "the Shoreham Inn has done a huge amount to bring people together," Stevens said.

When the Preservation Trust of Vermont brainstormed a list of elements that "make a great village" in 2007, "restaurant-café" was among the top six, along with post office, library, school, town office and general store.

But historians say that breaking bread at restaurants is actually a relatively new way to spin the threads of small-town community. And, as anyone who has ever tried to keep an eatery alive in such a place can attest, it's not a simple one.

About a decade ago, a group of restaurateurs used a community-building pitch to draw local investment to Claire's Restaurant and Bar in Hardwick, whose story landed in the pages of the New York Times. After six years, however, the restaurant closed — a reminder that the postcard ideal of a gathering place comes with plenty of challenges.

Historically, few rural American towns had a restaurant, said Amy Trubek, a cultural anthropologist and University of Vermont associate professor who has published books on both the culinary profession and home cooking. In nonmetropolitan areas, she pointed out, restaurants existed mostly to feed travelers, as the original Shoreham Inn did. "There was no tradition of eating out in everyday life because women cooked at home," Trubek said.

Not until after World War II did people start to dine out more regularly, thanks to the rise of the middle class and an increase in the number of women working outside the home, elaborated Jill Mudgett, a cultural historian who specializes in 19th- and 20th-century Vermont.

"Restaurants in small towns did not have a whole lot to do with community cohesion," she said, reiterating that they catered largely to out-of-towners and to single men renting rooms in town.

Mudgett and Cheryl Morse, a University of Vermont associate professor of geography who studies rural communities, both noted that earlier generations of Vermonters did gather over food — not at restaurants but at seasonal events such as chicken pie suppers and ice cream socials. While these traditions persist in some places, they don't provide the kinds of regular opportunities to bump into neighbors that reinforce community connection, Morse said. Restaurants are places where you can linger, she noted, while "people don't hang out at the town hall."

Although the residents of many small towns would love to be closer to a café or restaurant, the economics of providing that place to linger are sobering. "It can be hard to make money at that scale. You have to put value on the community service," said Trubek.

"They have to be the kind of restaurants that are really accessible to everyone," Morse added.

Locally owned restaurants have been struggling around the country for the past 20 years, said Tim Marema, editor of the Daily Yonder, a blog about rural people, places and policies nationwide. "In a lot of rural America, the institution of the eatery has become the Dairy Queen, the McDonald's, the KFC," he said. "It's really difficult in lots of places for an independent to make a go of it."

In Vermont, some restaurant owners, like the Dones at the Shoreham Inn or Kelden Smith at Samurai Soul Food, make their business work by catering to both locals and tourists. Others have cobbled together startup capital and customer commitment from locals to launch "community-supported" restaurants such as the Bobcat Café in Bristol or the now-defunct Claire's. In Peacham, it took more than a decade of community fundraising to open a central café.

Still, Morse noted, "a lot of towns just don't have the capacity to support a café or restaurant. They have to make do with a general store." Morse has studied the role of general stores in promoting rural community resilience. In addition to more traditional general stores such as the venerable Franklin General Store (see right), she cited local examples of the newer hybrid restaurant-meets-general store model: Parker Pie at the Lake Parker Country Store in West Glover, and the pairing of Harry's Hardware with the Den and Sarah's Country Diner in Cabot.

Like Marema, Morse has also observed the trend of chains becoming local gathering places. In some rural Vermont locations, for example, upgraded gas station convenience stores have added food options and places to sit, she said.

While it's easy to lament the decline of unique small-town eateries, Marema cautioned against idealizing them. "We romanticize that," he said. "We want those small businesses with the well-trodden wooden floor, the cash register that still jingles." He acknowledged that restaurants can help preserve local foodways and regional culture but added, "The coffee klatches are still happening, even if it's at fast-food places."

Still, it's hard to imagine a Maplefields customer writing an online review like one posted earlier this year on Facebook about the Halfway House Restaurant, Shoreham's other longtime favorite. The family-owned, diner-style spot is frequented by the local farming community and known for solid eats and housemade desserts. Reviewer and regular Bill O'Neill goes there, he wrote, for "very good home-cooked meals." Plus, he noted, "You also get a big slice of the community."

We visited seven eating and drinking places in Vermont that vary in their business models but all add vitality to their rural communities, along with a "big slice" of local color.

— M.P.

Shoreham Inn and Pub

51 Inn Road, Shoreham, 897-5081, shorehaminn.com

- Bear Cieri

- Shoreham Inn and Pub co-owner, Andrew Done

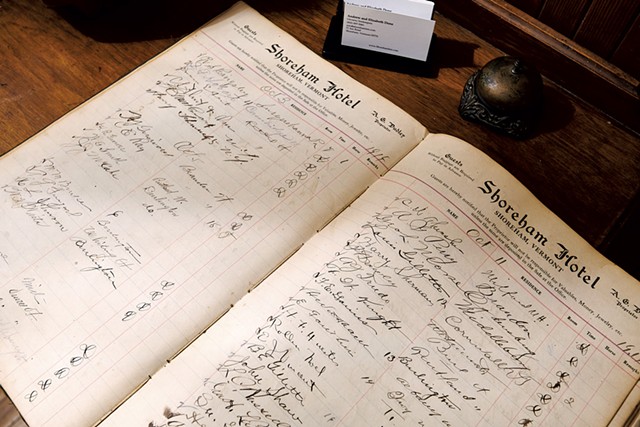

The guest book in the lobby of the Shoreham Inn is more than a century old. It contains columns for name, residence, remarks and "horse." Recent visitors have hailed from as far as Colorado and Alabama. None, apparently, brought a horse — but they did praise the cozy, wood-beamed pub and inn, which are more than 100 years older than the guest book.

Andrew and Elizabeth Done, who bought the historic property in early 2017, are hands-on owners. Andrew, a longtime hospitality professional who most recently worked in New Orleans, manages the kitchen. His wife is a cheerful presence out front and bakes all the from-scratch desserts.

Andrew described the menu as "home cooking, comfort-type food, not froufrou." A roster of mains checks all the boxes: steak, grilled chicken, baked haddock and a burger made with local beef. On a late-fall evening, the vegetarian offering featured butternut squash from Golden Russet Farm & Greenhouses, whose owners, Judy and Will Stevens, happened to be eating at the inn that night.

- Bear Cieri

- The Shoreham Inn and Pub guest book

The business sees a steady flow of tourists from July through foliage season, but the Dones very much value their local customers, too. The pub section of the menu, Andrew said, was designed specifically with locals like the Stevenses in mind. Occasional $11 specials that combine beer with wings or a burger also help keep a night out affordable.

For $10, a generous hill of mashed potatoes came topped with two well-seared Vermont-made bratwursts and a savory red-wine-and-onion sauce. The classic Caesar, which correctly includes anchovies by default, made a solid counterpoint to the "bangers and mash" richness.

For those with a sweet tooth, Elizabeth's dessert list presents an embarrassment of options. During a recent visit, maple-pecan cheesecake, devil's food chocolate layer cake, rum pumpkin chiffon pie and a butterscotch pudding all tempted. Our table of four shared the cake and pudding and found the latter a creamy, caramel-kissed pleasure.

Judy Stevens recommended the pies, though perhaps it was lucky for us that none was on the menu that night. One nice thing about this time of year, she added: Having fewer tourists makes more room for locals at the Shoreham Inn.

— M.P.

Franklin General Store

5243 Main Street, Franklin, 285-2033

- Stina Booth

- Sue and Bill Mayo, co-owners of the Franklin General Store

The other day, Art Davis walked into the Franklin General Store for a quick lunch — a bowl of housemade chicken noodle soup and a bottle of chocolate milk. He was in the middle of readying a new logging truck for use at his business down the road, A. Davis Agriculture Services. So Davis, 63, took his lunch to go and headed back to his shop.

"The store's our general meeting place," he said before leaving. "We stop in almost every day and buy our lunches and spread gossip." Back when he was 19, Davis recalled, logging with a team of horses in the Franklin County woods, his lunch was three sandwiches and a thermos of coffee.

These days, the general store on Main Street serves a daily hot lunch special to about 20 people, some of whom are loggers and sugarmakers. The noontime meal, usually $7.50, could be ham and scalloped potatoes with string beans; a hot roast beef sandwich and fries; or macaroni and cheese with a grilled natural-casing hot dog. The special usually sells out by 12:30 p.m. "Stragglers," to use co-owner Sue Mayo's word, arrive later for subs, sandwiches, soup and pizza.

Sue, 58, a Franklin native, owns the store with her husband, Bill, 64, who grew up in St. Albans. They bought the business in 2003, after Bill was laid off after almost 25 years at IBM. The Mayos have renovated the store over time, adding their own products to its provisions. The freezer holds stacks of Sue's pies, from-scratch beauties that include pumpkin, raspberry, maple cream, strawberry rhubarb and chicken pot pie.

Venison hunted by Bill and packaged as steaks and sausage is available (for a limited time) in the meat freezer. The cider inventory includes a hard cider, Just Franklin, made from a variety of apple Bill grows at his orchard near the Canadian border; he's patented the fruit under the name Franklin Cider.

Sue remembers the store from her childhood, when it was called O.H. Riley. A sweet shop and barbershop stood next door; the grange hall was across the street. Her grocery purchases were marked in a ledger and paid for at week's end by her father, who was a foreman at the pulp mill in Sheldon.

A store poster from decades past announces "Free Lunch Served on Thursday." Showing Seven Days the old notice, printed when T-bone steak was 79 cents a pound and bananas were two pounds for a quarter, Sue remarked, "So, does that answer your question about community?"

— S.P.

Harry's Hardware

3087 Main Street, Cabot, 563-2291, harryshardwardvt.com

- Courtesy Of Harry's Hardware

- Jam session at Harry's Hardware

Grocer Bobby Searles had operated the Cabot Village Store for about a decade when the next-door hardware shop and gas station hit the auction block in 2012. Searles wasn't interested in selling tools, he told Seven Days in 2017, but a small town is "a fragile ecosystem," and he felt compelled to buy the place. Villages turn into ghost towns, he pointed out, when they can't readily meet their residents' basic needs.

Searles ran the hardware biz for four years. "We tried to sell this store to everyone who walked in," he said.

In 2016, Johanna and Rory Thibault moved into a 200-year-old farmhouse around the corner. As they settled into the old place with their two children, they became hardware store regulars. Rory Thibault (now the Washington County state's attorney) was just coming off active military duty, and the family was ready to put down roots in Cabot. Searles' casual "Buy my store" proposition grew into a larger conversation: What does this town need? What's missing?

"We identified what we thought was a need in the community," Johanna Thibault said last week, "which was to provide a place for people to come together. There wasn't really anywhere to do that."

The Thibaults became half-partners in the business with Searles and extended the register counter into a full-length bar-top. In July 2017, they began serving beer, wine, and bar foods such as Scotch eggs and pretzels. Sarah's Country Diner, which operates a tiny dinette at the rear of the building, supplies additional soups and other snacks.

Now, when neighbors come in for a mousetrap or a box of screws, they often stay for a beer. "There's no separation" between the bar and the hardware store, Thibault said. "When we have music, you're sitting among the hardware. So there's oil for your car right there, and you're like, 'Oh, yeah, I needed to pick that up.'"

In fact, Thibault added, the financial cushion supplied by beverage sales has enabled Searles to expand the shop's hardware inventory; when someone comes in looking for a part, Harry's is more likely to have what they need.

Saturday night music showcases summon out-of-towners who dance among the rakes and shovels; on Sundays, locals strum, hum and drum away the afternoon at community jam sessions. The bar draws visitors to the nearby Cabot Creamery Visitors Center into town, too. In the past, Thibault said, tourists wouldn't come into the village. "They would go to the creamery and go back out again."

— H.P.E.

Samurai Soul Food

176 Route 5, Fairlee, 331-1041, facebook.com/samuraisoulfood

- File: Sarah Priestap

- Diners at Samurai Soul Food

Every restaurateur knows that January is no time to open a restaurant. Just don't tell Kelden Smith, who opened Fairlee's Samurai Soul Food in January 2017.

In a town with only 977 year-round residents, where the only other four-season restaurant was a decades-old pizza place, the tiny, super-casual restaurant was nonetheless an instant hit. "Everybody from town comes in," said general manager Amy Bruce. "We've just had an outpouring of locals who are grateful to have a place to go that's close by and different."

The décor is part bachelor pad, part tiki bar, part college dorm room. Strings of chile-pepper lights glow red against bamboo-lined walls. Posters depict a young Bruce Lee, circus polar bears on teeter-totters and clowns. An overhead television plays silent anime films. Languid goldfish swirl around the rocks and plastic plants inside a long tank near the door. Tibetan prayer flags adorn the doorways.

The food is not what you might expect, either. Locals crowded in to sample a funky Asian-fusion menu featuring kung pao chicken wings, lobster rangoons and wonton tuna nachos made with raw fish, spicy mayo and wasabi cream.

Bruce, who described the food as "fun," said, "Every dish has its own special twist; it's not your basic taco or burger. There's always one ingredient that sets it apart from other places."

Season matters bigly in Fairlee, which is home to two meandering lakes lined with second homes, at least eight kids' summer camps and an idyllic 18-hole golf resort. When the weather warms, Fairlee's population swells by thousands as out-of-staters sweep the cobwebs from waterfront houses and camp counselors entertain the scores of kiddos who sleep in canvas tents.

To accommodate those hungry masses, Samurai Soul Food added an outdoor patio in its first summer, doubling the available seating. But as the nightly lines persisted, locals retreated to their own decks and gardens and waited for winter's return. "We get overrun by summer people," Bruce said. "People from here wait for our downtime so they can get back in."

In this tiny town, the adage rings true: Good things come to those who wait ... for winter.

— H.P.E.

Carrier Roasting and Good Measure Brewing

17 East Street, Northfield, 485-4600, goodmeasurebrewing.com, carrierroasting.com

- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

- Nate Doyon working the counter at Carrier Roasting

On the Saturday before Thanksgiving, Carrier Roasting in Northfield hosted a pie social and fundraiser for the local food bank. People enjoyed slices of maple cream and devil's chocolate pie with a strong cappuccino or a cup of black coffee. By 12:30 p.m., as pie ran out, adjoining Good Measure Brewing was filling up with a different crowd: folks getting a jump on holiday cheer.

The café and taproom housed in a brick building are bound by walls and ownership. Over the past two years, the onetime IGA space has been revitalized into dual enterprises, each serving a double function: production facility and hangout. The café roasts its own beans; the taproom serves beer brewed in the back.

That double purpose is the key to the venture, said co-owner Ross Evans, who grew up in Northfield. "You have a place where you can produce something that's going to go out in the world," he said. "Yet people can come into your location, sit and consume your thing. We're bringing people to town."

Since January 2017, in this Washington County town that is home to Norwich University and about 2,000 people, roughly 10,000 people have come to the brewery-café, Evans said. Most of the customers are from out of town. "The businesses bring new money into Northfield that isn't otherwise there," he noted.

- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

- Scott Kerner pouring a beer at Good Measure Brewing

Evans, 37, and his brother-in-law, Scott Kerner, 43, co-owner of Three Penny Taproom in Montpelier, founded Carrier Roasting three years ago in Evans' parents' barn. They set up roasting equipment beside a pottery shop and sold beans through a subscription service.

In January 2018, having teamed up with Matt Borg, a roaster with experience at California's Blue Bottle Coffee Company, the business partners moved the roastery to the Good Measure Brewing building. Now, Carrier Roasting ships some 350 pounds of beans a week, packed in bags marked "roasted in Northfield, Vt.," to destinations from Burlington to Everett, Wash.

The goods that stay at 17 East Street, on both sides of the space, contribute to life in the village, patrons say. The day of the pie social, a Massachusetts couple who graduated from Norwich University in the mid-1990s sipped flights of beer in the taproom; their teenage daughter sat in the next room with a frothy coffee drink.

One of those alums, Rob Archambault, noted how times have changed. "There was nothing here when we were here," he said of his college days. "We drank beer at bonfires by the river."

— S.P.

Peacham Café

643 Bayley Hazen Road, Peacham, 357-4040, peachamcafe.org

- Hannah Palmer Egan

- Peacham Café

The people of Peacham gathered for decades at the Bayley-Hazen Country Store. When it closed in 2001, the town's 700-odd residents had no place to chat with neighbors over a morning coffee; nowhere to grab an easy takeout supper; no stop-on-the-way-home for milk or eggs. "We were used to having a gathering place," said former town planner Barry Lawson, where "you could pick up some goods or dessert and also meet people."

Shortly after the store closed, a group of citizens got busy. With help from the Preservation Trust of Vermont, they secured funding to buy and revive the store. By then, the original owner had sold off all the kitchen equipment. Undeterred, the group pursued plan B, Lawson said: Find another old building and set up shop there.

A decade passed before it found a viable home for the desired gathering place. In 2011, the municipality decided to offload the town-owned "bus barn" — located beside the old store, a stone's throw from the village green — for $1. Nonprofit Peacham Community Housing purchased the place, and a second round of fundraising netted $120,000, enough to transform it into a modest market-café.

Laborers from St. Johnsbury's prison camp kept renovation costs in check as workers gutted the 100-year-old building, reframed its interior, hung and painted Sheetrock and installed kitchen appliances. The business plan included ongoing funding in the form of slow-season rent subsidies and other financial supports to keep the restaurant afloat during hard times.

Finally, as the autumn leaves began to blush in 2014, local chef Ariel Zevon opened the café with a menu of stuffed French toast, farm-fresh soups and salads. In summer 2016, Caledonia County native Crystal Lapierre took over; these days, she runs the place with her twin sister, Shannon Pelletier.

Together, they wake the village with a morning caffeine fix — lately, using a shiny new coffee machine — along with breakfast sandwiches, housemade bagels with cream cheese and lox, and honeyed granola with yogurt. At lunch, the sisters' deli-style sandwiches, salads and wraps incorporate as many community-sourced meats and produce as the town's farmers can supply.

Lawson acknowledged that it's hard to run a food business in a small town. "The market is just not there," he said. But Peacham seems to have demonstrated that where there's a need, there's a way.

— H.P.E.

Hobo's Café

18 Cross Street, Island Pond, 723-4601

- Courtesy Of Hobo's Café

- Rob McComiskey at Hobo's Café

When Rob McComiskey was a kid growing up in Canaan, he loved Friday night dinners at Bessie's Diner. The whole town seemed to be there, he recalled. The camaraderie was enhanced by poutine, pizza and steak.

"That's the thing about a restaurant," said McComiskey, 35. "It brings the whole community together."

Now he and his parents are helping to build community at Hobo's Café in Island Pond, the barbecue restaurant the McComiskeys opened on Mother's Day 2017. Their son returned to the Northeast Kingdom from Colorado, where he'd been living and cooking for 13 years, to be its pitmaster.

"I was sitting there watching an awesome sunset over the Rocky Mountains, and the phone rang," McComiskey recalled. It was his father, Bob, calling with news from Vermont. "I bought a restaurant, and I want to bring barbecue to the North Country," Rob's father told him. "Are you in?"

"Yes, Dad, I'm in," he answered. Soon McComiskey was back in the Kingdom, living above the restaurant in the Essex County town of about 800 people.

"The beauty of barbecue is in its simplicity," he said. "You don't have to go off the wall to enjoy good food."

Hash brisket, pumpkin pancakes and coffee bring townspeople and recreators — campers, hunters and snowmobilers — to Hobo's Café for breakfast. Meat smoked over apple, hickory and maple wood fills plates at lunch and supper, served with two sides.

While the food may be all about enjoyment, the 48-seat café has also been a place for the community to take on weighty matters; in October, it hosted a forum on opiates in Vermont, led by Attorney General T.J. Donovan. He ate pulled-pork sliders and posted a thumbs-up review on Facebook ("Everyone should stop at Hobo's BBQ in Island Pond — great BBQ and conversation").

"It was very interesting," McComiskey said of the discussion. "It was about a serious epidemic, and it was really insightful. As a community, we're concerned about what's going on with this. We all care for each other, and we want better."

Hobo's Café served veterans at half price on Veterans Day. On Thanksgiving, a Canadian trucker with a load of Christmas trees wandered into the restaurant looking for a warm meal; though the place was officially closed, family and staff welcomed him to join the feast they were holding there. "It was a back-to-your-roots kind of feeling," McComiskey said.

On a regular day at the café, McComiskey particularly enjoys talking with his older customers. "I get to sit down and hear their stories," he said. "I've learned to stay humble. You have to stay humble to gain experience in life."

— S.P.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.