On New Year's Day 2019, Seven Days staff photographer Matthew Thorsen died from cancer — or, as we put it in our cover story tribute to him the following week, the disease "ushered" the beloved and brilliantly enigmatic artist "into his next great adventure." Wherever it is we go once we depart this mortal plane, Matt has had good company there these past 12 months.

Related Remembering Seven Days Photographer Matthew Thorsen

He was the first of several notable Vermonters to leave us in 2019, many of whom you may have read about. Henry Huston, who died in July, was a key figure in designing the Church Street Marketplace and Burlington's Waterfront Park. In September, scientist Cardy Raper died, just months after we interviewed the mycologist about her provocative and entertaining memoir, Love, Sex & Mushrooms: Adventures of a Woman in Science. October brought the loss of Paul Bruhn, who had been chief of staff for Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) and, more recently, the first executive director of the Preservation Trust of Vermont, among numerous other distinguished titles he held.

Activist and journalist Susan Green died in March — you might recall her regular byline in the Burlington Free Press and Seven Days years ago. Activist, filmmaker and onetime Richmond constable Roz Payne died in May, as did noted jazz pianist Dan Skea. If there's a band in the afterlife, it got a new jazz bassist in November as Ellen Powell left her earthly gig.

Of course, other Vermonters died this year, too — many you might not have heard about. We like to tell some of their stories in this end-of-year issue, as we've done annually since 2014. Whether or not their passing made the news, their lives impacted their communities in ways both large and small. Some were individuals who saw, heard or processed the world in a manner that changed us; some were people who made life better for others because of how they lived theirs.

— Dan Bolles

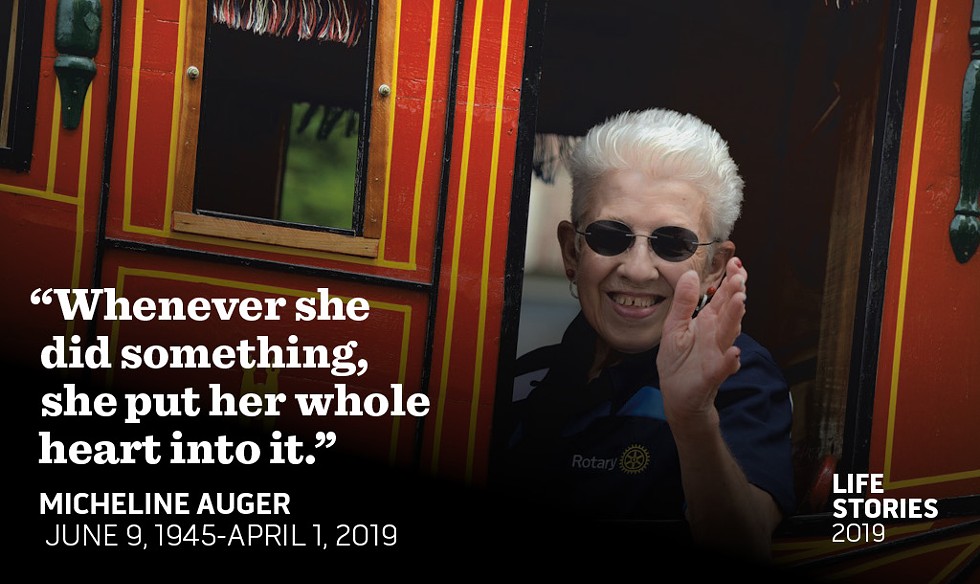

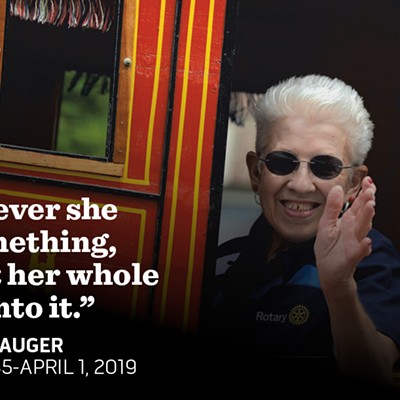

Micheline Auger

June 9, 1945-April 1, 2019

- COURTESY OF DAWN GREENWOOD

- Micheline Auger riding in a stagecoach in Newport’s centennial parade in June 2018

On a snowy night in December 2013, Corey Marcoux was driving to the Newport police station for his patrol shift when he spotted a small, bundled figure on Main Street, clearing the sidewalks with a shovel. Even from a distance, he knew it was Micheline Auger.

Micheline was a fixture on the streets of Newport. Nearly every single day, rain, shine or blizzard, she loaded the basket of her seated motorized scooter with a broom, a bucket and trash bags, then cruised downtown to begin her cleaning rounds.

In the summer, she would pick up cigarette butts on the sidewalk. "Without gloves!" recalled her sister-in-law, Therese Auger. "We were always trying to get her to wear gloves!"

Micheline often stayed out so late that the Newport Police Department, fearing she might be struck by a car, gave her a reflective vest. In the winter, Micheline cleared the stoops of the shops along Main Street. And not only did she shovel the sidewalks, said Marcoux, she even shoveled the strip between the street and the curb where snow piled up from the plows, so people could get out of their cars without stepping in slush. She did all of this for free, without complaint or recognition. Following a period of decline that likely stemmed from long-term health issues, Micheline was found dead in her Newport apartment on April 1.

That December 2013 night, Marcoux remembers, Micheline eventually stopped into the police headquarters to announce that she had cleared the front steps and the walkway. Marcoux thanked her for her service, then asked if he could take a photo of her to share on Facebook. Micheline agreed. The post, which received more than 1,700 likes, praised her selfless dedication to keeping Newport clean.

"I asked her why she does all this work, especially when she isn't paid for it," Marcoux wrote, "and she told me that she does the work for the exercise and to help the community. We believe a person such as Micheline should be recognized for her hard work and effort to help the community at her own expense."

Micheline, then 67, was already something of a local legend, for both her street-cleaning vigilantism and her habit of thumbing rides all over town. But the Facebook post mentioned a fact about Micheline that many people didn't know: At 21, she had been in a near-fatal motorcycle crash that left her with a chronic limp and lifelong cognitive difficulties.

Before the accident, Micheline had been enrolled at Lyndon State College, now Northern Vermont University, studying to become a teacher. The youngest of nine children, she grew up on a dairy farm in North Troy, where her family had moved from Granby, Québec, when she was nine years old. Micheline was a stickler about the non-Francophone pronunciation of her name; as she was fond of telling people, "It's Michel-in, like the tires, not Michel-EEN."

In her youth, Micheline was strong-willed and free-spirited. "She always tried everything," said Therese, the wife of Micheline's older brother Normand. At North Troy High School, she played basketball and softball; in her junior year, she was named Harvest Ball Queen. She liked dresses, but she didn't care about getting dirt under her fingernails.

She loved her independence so fiercely that when she started at Lyndon State, she insisted on getting her own wheels to ferry herself back and forth between home and the campus. After some negotiation, she convinced her mother and father that she should be allowed to have a motorcycle.

One evening in July 1966, as she was riding her bike home from Lyndon State along Route 5A, a boulder tumbled down an embankment into the road in front of her, and Micheline didn't have enough time to swerve out of the way. The collision left her in a coma for 54 days. The doctors told her family that if she ever woke up, she would never be the same.

- PHOTO COURTESY OF DANIELLE PAQUIN

- Micheline at her 2015 graduation party

When Micheline regained consciousness, her father, a former wrestler, refused to accept that his daughter might not walk again. According to Danielle Paquin, Micheline's niece, he made her do strengthening exercises every day. "He would say, 'Move your arms! Move your arms!' She would get frustrated, but she couldn't speak, and the more frustrated she got, the more she flailed," remembers Danielle, who was 10 at the time of Micheline's crash. "So it worked."

After months of recovery at her parents' house and a stint in a rehabilitation facility in Pennsylvania, Micheline could walk and talk again. For a time, she made money cleaning houses and dog sitting, but her occasional short-term memory lapses made it hard for her to keep a job. In 1994, she moved into an apartment on Main Street in Newport, and at some point after that — no one recalls precisely when — she started picking up litter on the sidewalks. That gradually morphed into her quiet, one-woman crusade against all instances of unsightliness in public spaces.

Before Sunday Mass at St. Mary Star of the Sea, Micheline would make her way through the pews and straighten every hymnal. She waged perpetual war on grass that grew between the cracks in the pavement. Her weapon of choice: a flathead screwdriver.

"I would see her on her hands and knees, wedging this screwdriver into the tiniest crack you can imagine," said Danielle. "I mean, who does that? Whenever she did something, she put her whole heart into it. She just wanted to make everyone happy."

In 2015, after Officer Marcoux's Facebook post went viral, Lyndon State College invited Micheline to commencement to present her with an honorary teaching degree. Danielle remembers her aunt being ecstatic.

"They told her that they would bring the diploma to her in her seat, but she insisted on going up there herself," Danielle said. When her name was called, she walked slowly to the stage, leaning on her cane for support. The crowd gave her a standing ovation.

But even after the recognition started pouring in — a community service award from Newport City Council, a spot on WCAX-TV's "Super Senior" segment, an honorary membership in the Newport Rotary club — Micheline was constitutionally incapable of taking it easy.

Late one night in summer 2018, Normand and Therese were returning home to Newport after visiting relatives in Québec when they spotted Micheline at the Maplefields on Route 5, where she liked to get flavored iced coffee. With kid-like glee, Micheline flagged them down. "Come see what I've been doing!" she said.

She led Normand and Therese across the street to the parking lot of a Dollar General, where she had been using her flathead to dig up weeds in the cracks of the asphalt.

"Look," she said, beaming at her handiwork. "Isn't it beautiful?"

— Chelsea Edgar

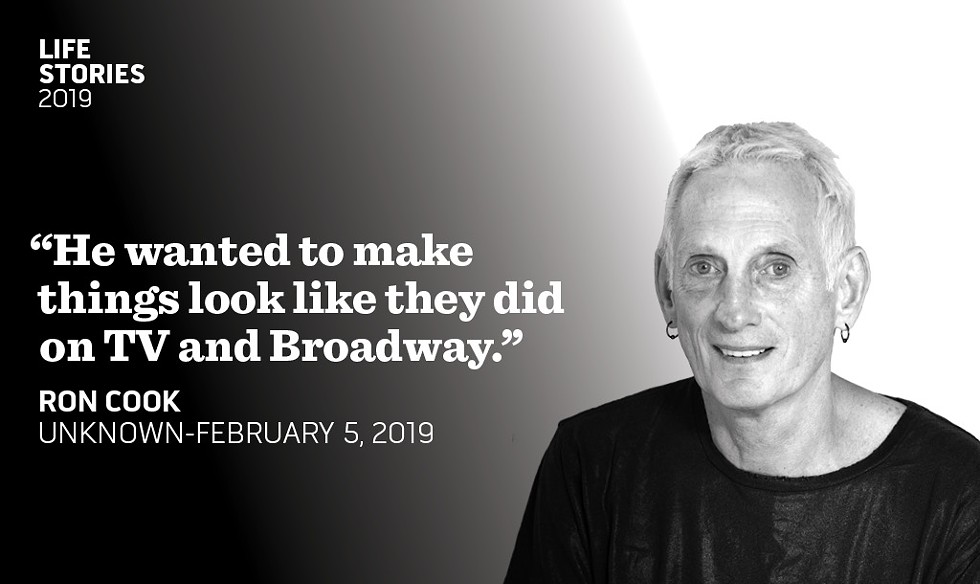

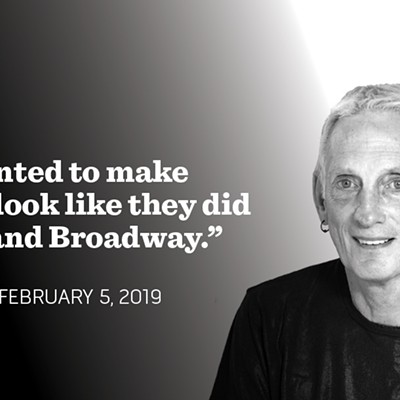

Ron Cook

Unknown-February 5, 2019

- Ron Cook

"Ron never told anyone his age," said Cynthia Mengis, sister of Burlington hairstylist Ron Cook. The seemingly ageless beautician kept his date of birth shrouded in mystery, to the point that his birthday embargo was practically a running gag. His close friends and family continue to guard his secret even after his sudden death in February, a result of unexplained intestinal bleeding.

Ron was well known in the Queen City's hairstylist community, having held chairs at long-gone establishments such as It's Hair! and Freestyle, as well as contemporary shops Tonic and O'M. He studied at the Sheldon Beauty Academy after collegiate stints at the University of Vermont and Brooklyn's Pratt Institute School of Architecture. His love of all things beautiful and glamorous won out over all previous interests. Mengis can't quite recall what he studied at UVM.

"He always did my hair," Mengis said. "I never had anyone else do it."

According to his sister, Ron's affinity for style and fashion started at an early age.

"He was very artistic and great at decorating," she said, recalling his enthusiasm for gussying up their one-room schoolhouse in Northfield for Halloween.

Ron was a man about town — literally. He was often seen walking Burlington's streets, because he chose not to drive for most of his adult life. He also never owned a cellphone or computer — though he did finally relent and pick up an iPad not long before his death.

Ron's raison d'être was making other people look good.

"He had a childlike wonder and love of talented and beautiful people," said Syndi Zook, who served as executive director of the community theater group Lyric Theatre from 2004 through 2017.

Ron was the company's go-to stylist and hair chair for many Lyric productions, starting with Oklahoma! in 1976. He was meant to helm the group's spring production of Mamma Mia! this year. The show's program included a tribute to Ron, which Lyric colleague and O'M co-owner Don O'Connell penned.

"He always had these little sayings," O'Connell said, noting Ron's catchphrase, "Whatever, whatever," which he might use in any circumstance.

The Lyric community deeply appreciated Ron's handiwork.

"It was great to have Ronnie, with his spectacular eye for glamour and detail," Zook said. "He really elevated Lyric's hair and makeup. He wanted to make things look like they did on TV and Broadway."

In addition to styling actors' hair, Ron would spend hours working on wigs. Some of his creations still exist in Lyric's extensive costume collection.

"He would put more work into a wig than anybody should," said O'Connell. "He would get into a wig and really wanted it to fit well. He looked at it like a little piece of art."

O'Connell first encountered Ron when he entered Burlington's beauty scene in the early '90s. The two became fast friends and, later, coworkers.

"There weren't a lot of guy stylists around," O'Connell said. "When you see somebody new in the business that you get along with, that has the same interests, it's nice to have that camaraderie."

Ron's work also took center stage at the Winter Is a Drag Ball, an annual bash featuring Vermont's most decadent drag queens and party people. Ron was particularly known for styling the ladies of the House of LeMay, the reigning mothers of the state's drag culture. The occasion was the perfect excuse to bust out pieces from his extensive collection of rhinestone apparel.

A master gardener, Ron also had an appreciation for natural beauty.

"If you go to a nursery, he had just about every flower they had," said Mengis, noting his love of poppies, tulips and daffodils.

"Anytime you would pick him up for anything, he had to take you on a tour of his garden," said O'Connell.

Ron was considered one of the kindest and gentlest people around.

"He didn't have a mean bone in his body," Mengis said.

"He was never critical," recalled Zook. "[But] he wasn't afraid to tell you how he felt about something. He would say, 'I would have done it this way' or 'I would have used this color.'"

For many years, Ron and his sister hosted an "orphans" Christmas dinner for all of their friends in the area who didn't have family close by or other gatherings to attend.

"He'd be the one who would set the table and see that the whole house was decorated, outside and inside," Mengis said. "He always tried to do things the very best that he could."

— Jordan Adams

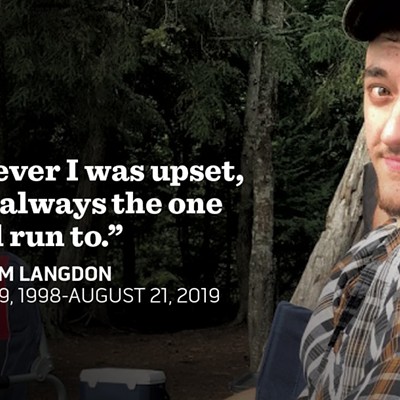

Chase Adam Langdon

February 19, 1998-August 21, 2019

- Chase Langdon

In middle school, gestures of kindness are often elusive. Perhaps that's why Devon Abner still remembers the day in seventh grade when he met Chase Langdon. Abner, who said he was often bullied in school, was sitting in the back of the bus when a kid he'd never seen before hopped on.

"I was like, 'You live up here, bud?'" Abner recalled.

Chase explained that he'd just moved to Waterbury from New Hampshire with his mom and his older sister. He then asked Abner matter-of-factly, "Hey, you want to be friends?"

It was the beginning of an easy rapport that stretched through the two young men's high school years at Harwood Union in South Duxbury and came to an end in August, when Chase passed away after a two-year battle with soft tissue sarcoma at age 21.

Neither he nor Chase liked school much, said Abner. They drove around together, hung out, and had "deep conversations" about life and relationships. They also played Airsoft, a recreational sport in which players engage in mock combat.

Sometimes, people have that one good friend who's almost like a sibling, said Abner: "We were kind of like brothers."

Chase's kindness extended to animals. His mother, Heather Allen Rivers, recalled that, a few years ago, before he became ill, her son heard about a dog that needed a home. Its owner, an older woman who owned a field in Northfield where Chase played Airsoft, had cancer and couldn't take care of it anymore. He agreed to take in the dog — without asking his mom if it was OK.

- Chase with mom Heather (left) and sister Lindsey

When Rivers told Chase she was too busy to care for a dog, he convinced his older sister, Lindsey, who lived nearby with her boyfriend, to take the border collie-Australian cattle dog mix, Dazy. Chase visited Dazy often, taking her for long weekends and bringing her to his friends' homes.

One of Lindsey's favorite childhood memories of her brother is playing in their backyard in New Hampshire with their father, Adam Langdon. They would pretend that they were in the Army, build tepees and eat foraged fiddleheads.

Indeed, being in nature made his son happiest, said Adam. The two spent much of their time together outdoors — hiking in the White Mountains, fishing on pristine Umbagog Lake on the border of New Hampshire and Maine, and taking summer camping trips with a big group of family friends.

In high school, Chase volunteered for several years at the Wallace Farm on Blush Hill in Waterbury. He started going there for school credit, doing odd jobs such as cleaning stalls and stacking hay bales, said the farm's owner, Rosina Wallace. But he enjoyed it so much that he would sometimes come on weekends and during the summer, with no more payment than a glass of milk.

Wallace remembered Chase as a quiet, hard worker with an ingrained sense of responsibility. "I found him to be extremely pleasant to work with," she said. "I appreciated the fact that I could give him a task and he would get the job done."

Whether it was hiking the steep, rocky Mount Lafayette-Mount Lincoln-Little Haystack Mountain loop with his dad or enduring radiation treatments that burned his throat and made eating difficult, Chase wasn't a complainer, said his mom. "His smile was amazing. So genuine and big," she recalled, noting his "perfect teeth." She added, "And he smiled when he meant it. Never fake or for no reason."

And Chase was a natural protector, especially when it came to the women in his life — his girlfriend, his mom, Lindsey and his baby sister, Vivienne, whom he called "Tiny."

"Whenever I was upset, he was always the one I would run to," said Lindsey. Her brother, younger by two years and seven months, would envelop her in his slim 6-foot-3-inch frame and tell her that it was going to be all right. "He would always hug me and wouldn't judge me," she said.

- Chase at his senior prom, April 30, 2017

Chase had hoped to go into the military after high school, but then came the cancer diagnosis — just one month after he graduated. He was born with a genetic condition called neurofibromatosis, or NF1, that generated a peripheral nerve sheath tumor at the base of his skull that wrapped around his spinal cord and touched his esophagus. The location of the tumor made it difficult to treat, and it became very aggressive, said Rivers.

Though he never realized his dream of joining the armed forces, Chase found a band of brothers in the Green Mountain Sentinels, a Barre-based Airsoft team that he helped form several years ago. He loved the sport and would never pass up the chance to play, said fellow Sentinel and friend Bailey Caple.

"Chase was great because he had the mindset of 'Let's just go play and figure out the rest later," wrote Caple in an email. "The happy, energetic spontaneity was something we all looked forward to anytime we got to spend time with Chase."

When Chase was diagnosed with cancer, the Sentinels gathered less frequently, "until we eventually stopped playing," wrote Caple, "because we felt it wasn't right of us to play the game if we couldn't share those moments with Chase."

He added, "He was a one-of-a-kind person."

— Alison Novak

Dion "Skeeter" Lawyer-Sanders

April 8, 1953-October 24, 2019

- Skeeter Sanders at the WGDR studios at Goddard College

Skeeter Lawyer-Sanders had a playful relationship with words. Take, for example, the typical intro to his weekly radio program. "Smooth jazz, with a touch of soul, from the heart of the Green Mountains," he would purr in his dusky baritone, drawing out "smooth" like he was stretching a skein of silk. Then, "Soft and warm. Welcome to 'The Quiet Storm.'"

Skeeter hosted his nationally syndicated show "The Quiet Storm" on Goddard College radio station WGDR for more than 20 years. Listening to his jubilant, often rhyming wordplay, you'd get the sense he dug talking about the music on his "smooth and cool magic carpet ride" as much as he dug spinning it.

"His radio show was his life," said Kris Gruen, director of WGDR and its sister station WGDH in Hardwick, which also broadcast "The Quiet Storm." Skeeter hosted the show until September, when congestive heart failure began to diminish his health. He died from the illness on October 24, at age 66.

Skeeter was born and raised in New York City. According to his younger brother, Andre Broadnax, Skeeter loved sports and music, though he wasn't especially adept at playing either. However, over the years he developed a deep appreciation for jazz, which he passed on to his kid brother.

"He definitely got me onto that: Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong," said Andre, who lives in Maryland with his wife and three children.

After high school, Skeeter studied journalism for a semester at a city college. When he was 19, his mother, Alice Alvin Braodnax, died at age 48 from congestive heart failure. (Years later, Skeeter's sister Gisele would also die at age 48 from the same condition. As a result, Skeeter rarely drank and never smoked.)

Soon after his mother's death, he left NYC for San Francisco, where he lived for 25 years.

"When his mom died, it did a number on him," said Skeeter's wife, Ellie Lawyer-Sanders, who lives in Hinesburg. She added that Skeeter's mother gave him his nickname because he was so tiny as a child, like a mosquito.

His move west following his mother's death "was also when he came out of the closet," she continued, explaining that her late husband identified as bisexual.

Skeeter moved to Vermont in the late 1990s, which is when, according to Ellie, "he reluctantly had to learn how to drive." She said he never quite took to driving like he did to the radio.

"We had some hairy rides, that's for sure," she said, chuckling.

Skeeter and Ellie met through a dating website in 2006. The couple was handfasted, or betrothed, in May 2007 — Skeeter was a pagan, which Ellie described as "a lot of fun." They legally married that July.

Ellie noted that Skeeter "never made a cent" from producing "The Quiet Storm," though he did work as an overnight DJ at WNCS-FM the Point for three years. Instead, he took odd jobs to make ends meet and give him time for his show — he worked as a custodian at Saint Michael's College, in the warehouse at FedEx and as a cashier at Shaw's Supermarket, among other gigs. She described her husband as a "tried-and-true hippie," right down to his left-wing politics.

Skeeter was a frequent and passionate letter writer to Seven Days, riffing on everything from the strategic folly of local Democrats and Progressives to the nuances of sexual identity. For a time in the late 1990s he wrote a column for the now-defunct GLBT newspaper Out in the Mountains called "Skeeter Bites."

Skeeter's progressive worldview sometimes caused friction in their relationship, Ellie admitted. And, she added, their mixed-race marriage caused tension within her family. The couple separated in 2015 but never divorced.

"Skeeter loved me, I know that," said Ellie. "But he was a jazz guy from the city, and I'm a country girl."

The roots of "The Quiet Storm" can be traced to Skeeter's time in San Francisco. In an interview at Burlington community radio station WBTV-LP, where he also deejayed briefly, Skeeter said he created the show as an homage to two Bay Area stations he listened to most: one a smooth jazz station, the other a "24-hour quiet storm R&B format." His goal, he explained, was to fill what he saw as a disappearing niche for smooth jazz on commercial radio.

"It was the only smooth jazz and R&B program in Vermont, as far as we knew," said Gruen. "Skeeter brought an essential cultural piece to central Vermont, because his show wasn't just music; it was a lesson in an era and a style of mostly African American music that isn't talked about enough in Vermont."

Gruen, who has been at WGDR-WGDH since 2010, called Skeeter the most committed community radio programmer he's ever met — "a patron saint of GDR." He highlighted the DJ's "classic, smooth jazz voice," as well as his lyrical on-air approach. "He would deliver these quips, these small poems — it was over-the-top for community radio," said Gruen. "But it was also excellent, and we loved it. It comforted people to have his show there."

Among those people was Reuben Jackson. The former host of Vermont Public Radio's "Friday Night Jazz" program saw in Skeeter a kindred spirit — he even cohosted a show or two with him.

"Skeeter's program was my weekly letter from home," said Jackson, who now lives in Washington, D.C. He praised the show's range and the "autumn-cool delivery" of its host. "He had a generosity of spirit and a deep love for music, radio and people," Jackson continued. "Lucky us."

WGDR-WGDH operations manager Dave Ferland has been at the station since 1996. He called his friend "an affecting and affectionate presence" and noted that Skeeter was "a deep study of his craft." That professionalism shone through in his show, said Ferland, but it was merely a vehicle for something else: his heart.

According to Ferland, Skeeter signed off with the same outro for 20 years. "I'm pretty sure that means he meant every word," he said.

That closing riff is a bit long, but here's Skeeter signing off one last time:

"And so as I prepare to walk out the door, I'd like to say in parting that may each of you always walk in beauty and appreciate the great mystery of the Earth and the cosmos. May each of you be thankful and forgiving of yourselves and of others, not just today but every day of the year. May each of you go forward on your path of light in peace, living always by your hope and never by your fear. May each of you live for as long as you want and never want for as long as you live. May each of you live to be 100 years old and me 100, but minus a day, so that I'll never have to know that nice people like you have passed away."

— Dan Bolles

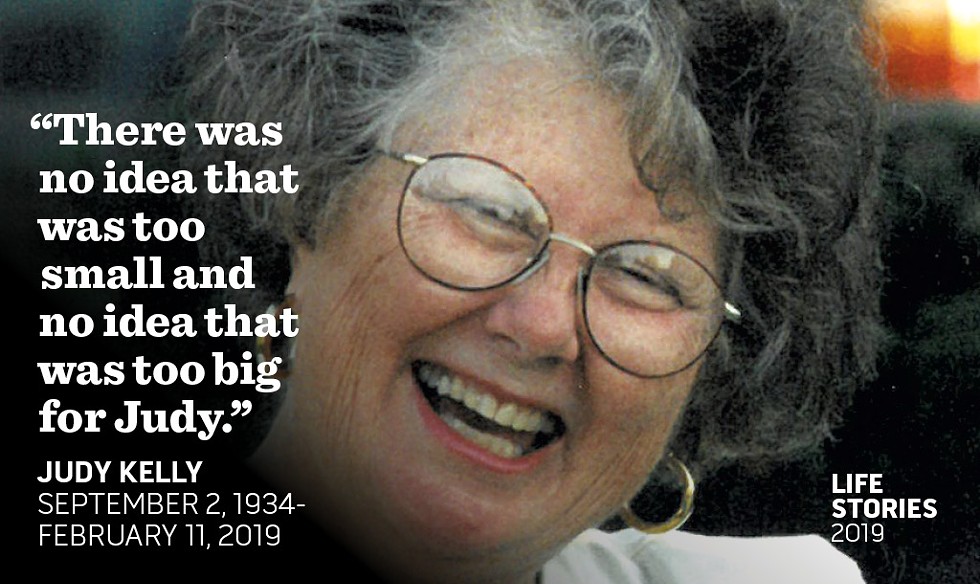

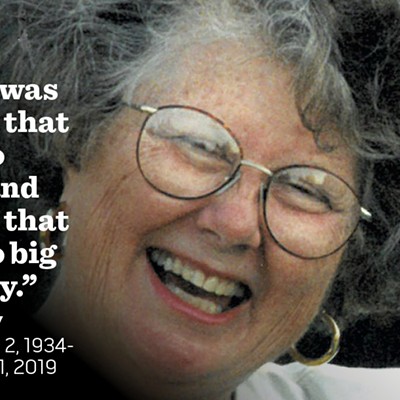

Judy Kelly

September 2, 1934-February 11, 2019

- Judy Kelly

In 1970, when Judy Saurman and her family moved to Vergennes from Chicago, she couldn't sleep at night. Cows kept her awake. The animals were unfamiliar and not entirely welcome neighbors.

"She was a city girl all the way," Judy's daughter, Ann Simon, said by telephone from Albuquerque, N.M. "Holsteins grazing [were] driving her crazy."

The Saurmans left the herd behind after a year, when they moved to Shelburne. The cows might've been the only living beings Judy Saurman Kelly didn't fully embrace.

In 49 years in Shelburne and Burlington, Judy Kelly amassed a large and devoted group of friends. (Her name became Judy Kelly in 1984, when she married Bill Kelly. Her first husband, Kenneth Saurman, died in 1980.) Friendships with Judy grew over egg salad sandwiches at her South End home, at meetings to establish Burlington City Arts, traveling overseas, painting watercolors and protesting war.

"Judy was everybody's friend," said Bill, her 87-year-old widower. "She valued friendships more than anything else." Judy died of pulmonary fibrosis on February 11, the Kellys' 35th wedding anniversary.

Judy taught art to a generation of middle school students in Shelburne and was the longest-serving board member of BCA. A political activist, she ran for public office twice, including as a Democratic candidate for alderman (a precursor to city councilor) in March 1985 in Burlington's Ward 6. She lost by 15 votes, according to city records. "There was a snowstorm the day of the polls," Simon said. "We blamed it on the snow."

Judy Belle Jewell was born into a creative family in Detroit in 1934. Her very name suggests she was spotlight-bound. "It was a perfect name for a burlesque marquee," Bill said.

Judy's father, James Jewell, ran a radio theater company, the Jewell Players, and was creative director for "The Lone Ranger" radio series and producer/director for "The Green Hornet" series, according to family members.

- Judy Kelly

When Judy was in high school, the Jewells moved to Evanston, Ill., where she studied radio and theater at Northwestern University. After graduating, she moved to Chicago for a job with NBC television, working her way up from copy assistant to the broadcast team, Simon said.

In 1970, Judy and Kenneth and their young kids, David and Ann, moved to Vermont, where Kenneth was a professor of education and social services at the University of Vermont. Judy earned her master's degree in education and began her teaching career in Shelburne. Students walked from school to the Shelburne Craft School for art classes.

"She was very vivacious and very much interested in the children," recalled Kathleen Speedy, who taught fourth and fifth grade in Shelburne for 25 years. "She was a very loving-type person" who made "every child feel like they were special in art and had something to contribute."

In 1980, after the death of her husband from cancer, Judy became a single working mother of two teenagers.

"She was totally freaking out," Ann said. "She had two college-bound kids, so she took on extra work and started teaching [as an adjunct] at the university."

In February 1983, Judy went on a date to a B.B. King concert at the Flynn Theatre with Bill Kelly, an associate dean at the University of Vermont College of Agriculture. A year later, they married and moved from their respective homes in Shelburne to Burlington.

Judy's work for the arts extended beyond the classroom to BCA, an organization she was instrumental in founding and of which she remained a devoted advocate, said executive director Doreen Kraft. Judy served on its two boards — the formative one and the one that guides the organization — for 30 years. Kraft said she's never known anybody "who cherished friendship as deeply" as Judy.

"She was fearless about diving in with two feet and working," Kraft said. "She always had 100 ideas, and she was just so generous, always saying, 'We could do this at my house.' There was no idea that was too small and no idea that was too big for Judy."

Her ideas and enthusiasm were a vital element of the Monet Mamas, a group she cofounded in 2001. Its half dozen or so friend-members still meet every Wednesday to make art and eat lunch, taking turns hosting the gathering.

Sometimes the women paint on their own. Other times they work together on projects, including making a cookbook of their Monet Mama soups. Kelly typically spearheaded the projects.

"We were like students of hers, and we had great fun together, a lot of laughs," said Roberta Whitmore, a Monet Mama and friend of Judy's. "She just radiated such energy."

Two years ago, Judy published a book that she wrote and illustrated, Where the Tar Road Ends, about living in Botswana with Bill in the early and mid-1990s. The volume is composed primarily of letters she wrote to friends and family from Africa. It concludes with two letters written in Burlington, including this excerpt from December 1997:

"Talking about the things I miss takes me into this Christmas season and the times past that I remember as being important to us: home, friends, generosity, kindness, and good times. That seems to be what it's all about, whether we are at home or away."

— Sally Pollak

Mary Anthony Cox Rowell

April 14, 1932-January 15, 2019

- ESY OF JOAN BARTON

- Mary Anthony Cox Rowell in the 1980s | Mary Anthony and her husband, Morris

Mary Anthony Cox Rowell was born an Alabama gentlewoman, trained in Paris as a concert pianist and became a legendary music teacher at the Juilliard School in New York City. But for 39 years, as she traveled and taught, her heart remained securely rooted in the village of East Craftsbury and her midlife marriage to a Vermont dairy farmer.

At Juilliard, Ms. Cox was the respected, even feared, chair of the ear-training department, an expert in the French method of solfège, or aural note recognition. Wynton Marsalis once recalled her as his most memorable Juilliard teacher. On her death in January, students swapped stories of her Southern wit and warmth — she often called them "honey" — and her demanding standards.

"Ms. Cox was very likely the best classroom teacher I've ever had," American composer Jonathan Newman wrote after her death. "She didn't just train your ear, she taught you how to be the best performing musician you could be, and she did it with sardonic wit and her unmistakable drawl," he continued. "She scared me witless, and I adored her, and I'll never forget what she did for me."

In Craftsbury, though, she was not Ms. Cox but Mary Anthony, the wife of Morris Rowell, stepmother to his five children and grandmother to their children. She was a founder and moving force behind the Craftsbury Chamber Players. And she was the host to a parade of performers who each summer filled the Rowells' seven-bedroom, three-piano farmhouse with music.

"Even though she was so busy, going all the time, she was really great at giving you undivided attention," Mary Anthony's granddaughter Annie Rowell recalled recently. "When you came into her house, she would say, 'Well, hello, my lady queen.' You felt very special when she called you that."

Mary Anthony Cox — don't dare call her "plain old Mary," one former student warned — was the only child of a genteel middle-aged couple in Montgomery, Ala. At 6, she demanded piano lessons of her pianist mother; by 12, she was teaching her own students. At 16, she moved to Paris and studied music theory with Nadia Boulanger, who is often described as the most influential music teacher of the 20th century.

Mary Anthony was nearing 30 when she enrolled at Juilliard in the early 1960s. She was recruited to teach ear training there even before earning her degree. The school soon became her permanent academic home.

In 1966, several New York-based summer residents of the Northeast Kingdom arranged for Mary Anthony and three equally cash-short fellow musicians to escape the city heat and spend a couple of months in a rent-free Craftsbury home. The friends began playing informal concerts in the Sterling College dining hall. They quickly attracted an audience, and the Chamber Players were born. The classical music group became a summer fixture in northern Vermont at a time when high-quality chamber music was a rarity in the state.

Among Mary Anthony's summer friends in Craftsbury were Morris Rowell, a dairy farmer and farm equipment dealer, and his music-loving wife, Carol. Mary Anthony taught the kids piano and, with her own mother, sometimes joined the Rowell family for Sunday dinner.

Carol Rowell died after a long illness in 1973; Mary Anthony and Morris Rowell married in 1974.

What seemed from the outside an unlikely union was built on Morris' gentle warmth and a similar generosity of spirit underlying Mary Anthony's formal manner and steely gaze, said David Rowell, her stepson.

They both loved music — not just Mary Anthony's classical repertoire but bebop and swing, which could be heard at venues around the Kingdom on a Saturday night.

"She was high mannered but not a snob," her stepdaughter Frances Rowell recalled. "They'd go out and dance like crazy."

From the date of her marriage to Rowell, Mary Anthony commuted weekly — for 35 years — during the school year from Craftsbury to New York City. She would head to the Burlington airport on Sunday evening and return on Wednesday or Thursday evening.

"I don't care if there was a blizzard, she was going to go. If the plane didn't fly, she'd take the bus. If the bus didn't go, she'd take the train," David said. "She was not going to be held down."

The couple's devotion was clear to all. Morris never missed a Chamber Players concert and often drove Mary Anthony to the airport and back. She telephoned him, morning and night, when she was in New York.

"I remember she said one time they were talking at night and he went to sleep, right on the phone," David recalled.

Together they helped two of Morris' daughters, Frances and Mary, finish the training they needed to become professional musicians. Together they hosted big midday Sunday dinners for family and friends, including the changing cast of musicians who made up the Chamber Players.

For more than 30 of its 53 years, the summer group was Mary Anthony's operation, down to the last detail. "She was a force of nature keeping things going," Frances said.

Mary Anthony assembled the concert programs by her own formula: one unfamiliar, sometimes challenging, piece of music sandwiched between masterworks from the classical repertoire. She invited the musicians, managed the volunteers and even monitored the dress of the teenage ushers — no untucked shirttails, please! Behind the scenes, Morris kept the musicians fed and housed, earning a reputation for his pies and hospitality.

In the years after 2010, Mary Anthony began to suffer dementia. She retired from Juilliard in 2013 after 49 years, just short of the 50 she had been determined to reach. In 2014, she stepped down from the musical leadership of the Chamber Players, to be succeeded by her stepdaughter Frances.

Morris cared for his wife as her illness deepened, until his own death from leukemia on December 28, 2017. She died 13 months later.

"Mary Anthony had drive and dedication, but she also valued a sense of community," said Ned Houston, a Craftsbury resident and longtime president of the Chamber Players board. "She was a person of the South and a New York person, yet she found a home here, a feeling of home. She enjoyed being a vital part of this northern Vermont community."

— Candace Page

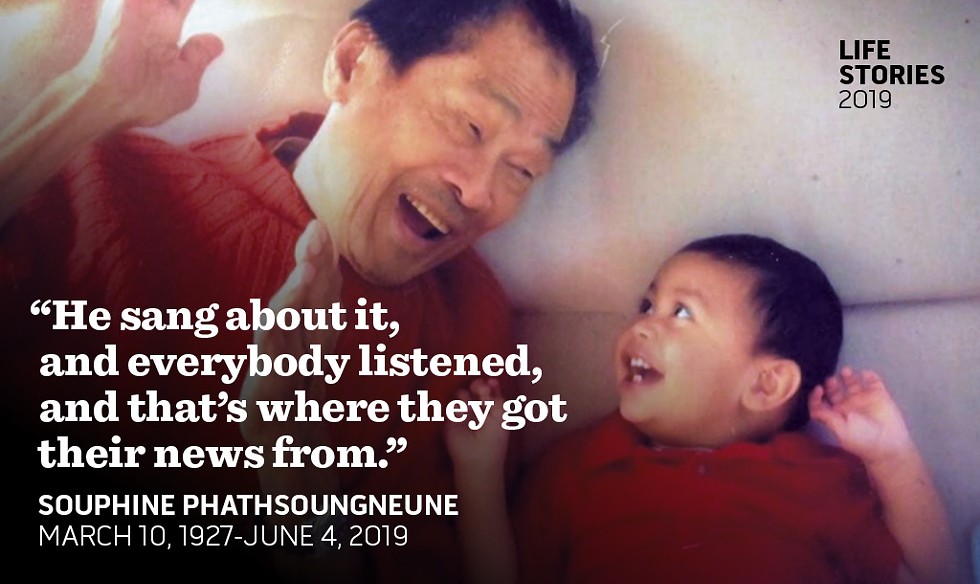

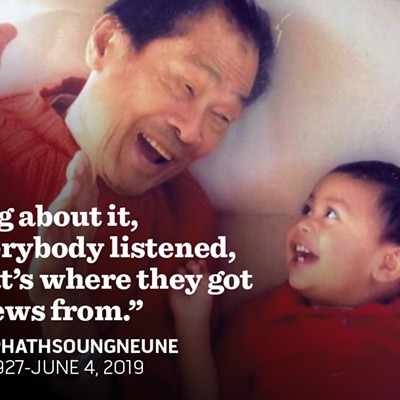

Souphine Phathsoungneune

March 10, 1927-June 4, 2019

- Souphine Phathsoungneune with his grandson Gabe

Most Vermonters wouldn't know it, but Souphine Phathsoungneune was famous. In his native Thailand and later in Laos, Souphine was a musician, singer and songwriter — comparable, according to his friends and family, to a rural Lao Elvis Presley. As a child, he taught himself to play the khene, a bamboo instrument, and began to sing and write music. He traveled throughout the country, singing Lao folk music and training other singers and musicians. The music is called lam, and Souphine was a master.

War came to Laos, and the broader region, in the 1950s. In a time when many Lao people were illiterate, Souphine's music was more than entertainment — folk music was the equivalent of a newspaper.

"His music was about what was going on with the war," said Souphine's daughter, Dokoi Sindi Phathsoungneune. "He sang about it, and everybody listened, and that's where they got their news from."

Eventually, life in Laos became too dangerous for Souphine and his wife, Phady. They left for a refugee camp in Thailand in 1972. Then, in 1980, they immigrated to the United States, while Phady was pregnant with Sindi, the couple's fourth daughter.

- Souphine Phathsoungneune

In a song written in 1995 and translated on the Vermont Folklife Center's website, Souphine described the experience of escaping Laos as refugees.

"We had to move out from our old land," he sang in Lao. "Aunts and uncles, grandmothers and grandfathers float in the Mae Khong River, float across to Thailand ... Everybody had to go by themselves and not see each other again. Everybody had to escape from death, and had nowhere to go."

The couple's first placement was in Chicago. Souphine and Phady didn't speak much English, and the transition was hard. But things improved for them in 1981 when they moved to Brattleboro, where the mountains felt more familiar.

"It really touched him and reminded him of back home," Sindi said of the southern Vermont landscape.

In Brattleboro, Souphine became an anchor of the Lao and Thai communities.

"My dad was respected, and everyone wanted to come and meet him. Also to have food," Sindi recalled. "Growing up, every weekend was filled with people. If we had any type of Buddhist parties, ceremonies, it would be held at our house."

Those gatherings weren't limited to just Lao people. Connie Woodberry, who was a caseworker with the Office of Refugee Resettlement, said Souphine and Phady's embodiment of Lao culture allowed many American-born Vermonters to experience it for the first time.

"You just felt like you were in Laos. He embodied the culture," Woodberry said. "It was really a rich experience ... for people who knew Lao culture and people who didn't."

- Souphine playing the khene

Even when it was just family, Sindi said, the house was full of music. Souphine would write music, and Phady would sing. Her father was also a painter, and Sindi remembered sitting with him watching Bob Ross on television — although her father would often paint something other than what Ross was painting.

"He really was an awesome artist. He would paint murals of anything that would come to mind. Mountains was his thing to paint," Sindi said. "He was like my go-to person. I was definitely Daddy's girl."

Souphine was also close with his two grandkids and two great-grandkids. Sindi's son, Gabe, was always greeted by a joyous hug from his grandfather. The two would swing together, eat popcorn and watch wrestling.

Souphine was also funny. Even people who didn't speak Lao and didn't understand many of his jokes found his animated manner hilarious.

"He's a storyteller. He also found humor in everything," Sindi said. "[Even if] you didn't understand him, you laugh with him. Because you just feel it." She added that her father's nickname was Banana, though she wasn't sure how he got it.

For years, Souphine's musical skills flew under the radar outside the Lao community. Despite his renown, he had to work several jobs to make a living in the U.S. He was, at various points, a dishwasher, maintenance man and janitor.

"We were fairly well off before the war. And then the war just turned their world upside down," Sindi explained. "No money, nothing. We had to go to a refugee camp ... The sacrifices that him and my mom made for our family, for their kids — that's what I'm grateful for."

Sindi said that her father had always encouraged her to get an education. When she was finally able to commit to getting a college degree, she was in her thirties and had a child, so she went part time.

Sindi said her father would joke, "Hey, when are you gonna finish school? You should be a doctor by now." But she said he always supported her. He was in hospice when she finished her bachelor's degree.

Sindi, Woodberry and others have said that upon return trips to Thailand and Laos, they encountered people who knew Souphine or had made music with him. Countless lam musicians count him as a trainer and mentor.

- Souphine Phathsoungneune

Souphine received grants from the Vermont Folklife Center and the Vermont Arts Council. With Phady and central Vermont poet Phayvanh Luekhamhan, he wrote a bilingual performance that combined his music with Luekhamhan's poetry, called "I Think of This Every Time I Think of Mountains."

Working with Souphine "helped to affirm my art when I was still exploring it," Luekhamhan said. "And he helped to make the bridge between [my art] and the rest of my Laotian community," she continued, adding that Souphine's renown in that community was beneficial to her, as was his humility.

Leslie Turpin, who teaches at the School for International Training Graduate Institute in Brattleboro, did her doctoral dissertation on memory in Lao American communities. In 2009, Turpin nominated Souphine for the Governor's Heritage Award, which he received.

Sindi said her father was key to carrying on traditions in Vermont's Lao American community. She's not sure what will happen now that he's gone and many of the children of Lao immigrants have scattered.

"I'm really so grateful that he was able to show the people of Vermont where he came from," Sindi said, "and the type of music that enriched his life, and how his music and his writing brought the community together."

— Margaret Grayson

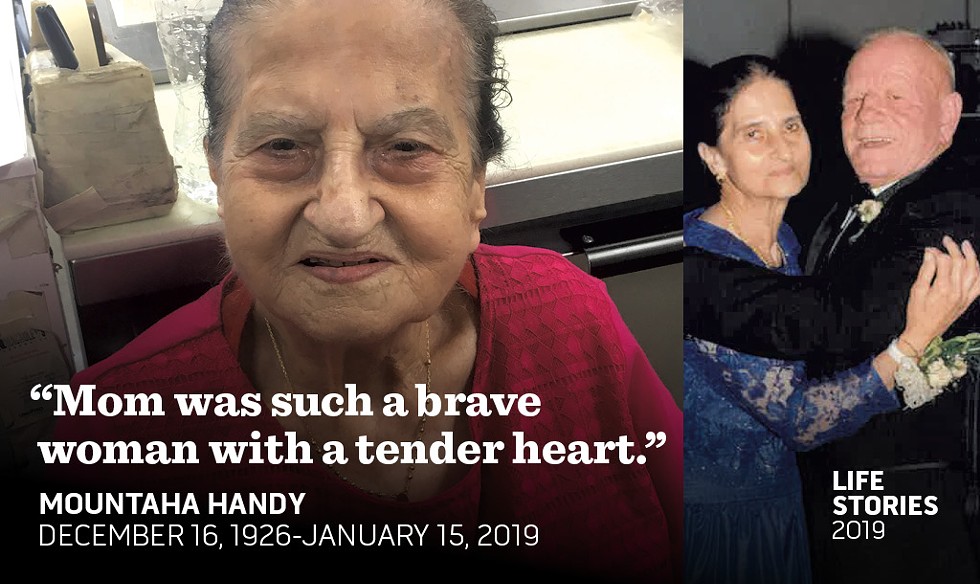

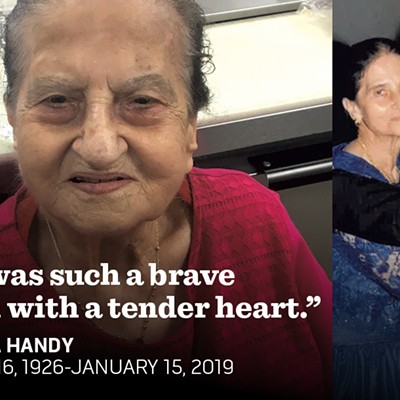

Mountaha Handy

December 16, 1926-January 15, 2019

- Mountaha Handy | Mountaha and her husband, Salamin

Family and friends remember Mountaha Handy of Colchester as a small, quiet woman who was as sweet as the candy she sold — until, that is, someone tried to steal from her store. Then she'd grab hold of them with the fierce persistence of an attack dog and not let go.

Burlington night owls who've frequented the Simon's Downtown Quick Stop & Deli, at 93 South Winooski Avenue, will likely remember Mountaha — known to many customers simply as "Mama" — who died in January at the age of 92 after a brief illness. Virtually every night of the week, from 11 p.m. until 6 a.m. for more than 30 years, Mountaha could be found alongside her older daughter, Joan Handy, sitting on a chair by the register, greeting patrons and bagging merchandise.

"She just loved being at the store," Joan said. "She got compliments on how beautiful she was and got her hands kissed I don't know how many times a night."

Though Mountaha occasionally napped during her overnight shift, mostly she kept a keen eye out for thieves.

"My gosh, could she catch shoplifters!" said her oldest son, Gabe Handy. "She once saw someone swipe two cartons of cigarettes and run out the door. She ran after him [and] hung on to his jacket, and he dragged her up the driveway. She wouldn't let go until some police officers rushed over and arrested the guy." The cops later confiscated the cartons as evidence.

"Up until a month before she died, she talked about how she never got those cigarettes back," Gabe added with a chuckle. "That was Mom."

Another time, Joan recalled, a man tried to rob the store, repeatedly saying, "I want the money!" and threatening Mountaha with a knife. Unfazed, she went after him with a police nightstick, which she kept behind the counter.

"She kept swinging it at him and saying, 'Go away!'" Joan said. When the police arrived and watched the security camera video, they got a good laugh out of it. "Mom was such a brave woman with a tender heart," she added.

Mountaha's silent strength likely was born from her poor upbringing in Ghadir, Lebanon. At age 13, she went to work in the tobacco fields of the Maronite Catholic Church, where she met her future husband, Salamin Handy. The couple married in 1951 and began raising a family. In the early 1960s, Mountaha helped Salamin run a small gasoline trucking company in Lebanon, which grew into a Mobil Oil distributorship for aviation fuel.

However, when war erupted between Lebanon and Israel in 1967, Salamin had to sell his business — all the jets and roads to the airport had been destroyed — and he immigrated to the United States in 1968. Mountaha joined him in Burlington the following year with their six children: Gabe, Charlie, Joseph, Joan, Tony and Laura.

Gabe, who was 16 at the time, remembers how his mom would bake Lebanese pita bread on an electric stove in their garage on Pleasant Avenue in the New North End. In those years, none of the local stores carried the Middle Eastern staple. The smell of baking pita bread attracted the neighborhood kids, who'd wait in line outside to get some.

- Mountaha (right) with her childhood friend Nadia Abdullah

"She didn't know how to speak ... English, but she knew how to please those kids, and she would pass out hot loaves of bread right out of the oven," Gabe remembered. "I think she gave out more than she kept for us. But she enjoyed it."

Salamin and Mountaha opened Handy's Texaco on South Winooski Avenue, which ultimately grew into the Simon's chain of convenience stores. A stay-at-home mother in the early years, Mountaha regularly cooked lunch and dinner for her husband and his family, who worked at the downtown gas station, Joan explained. Each day she would bring them Lebanese meals, which typically featured cut cucumbers, homemade stuffed grape leaves, kibbeh — a Lebanese dish made with ground meat, grains and onions — and kafta, or Middle Eastern meatballs.

Though Mountaha enjoyed visiting with people, Gabe said, sometimes her hospitable nature worked to their detriment. Once, his father hired a contractor to add a room to the back of their house.

"That was supposed to be maybe a 30-day job. That guy was there for four months," he remembered. "My mother would keep him busy talking to her, [and] she would feed him lunch and dinner. They probably had five or six cups of coffee a day."

But if Mountaha took the time to visit with the people, that was just fine with George Burnes. As owner of the Capital Candy Company in Barre, Burnes, 71, sold sweets and other merchandise to Mountaha for about 40 years and said he always looked forward to seeing "Mrs. Handy" in the store late at night. Especially during the Easter and Christmas holidays, he said, she'd come to him to buy special treats for her grandchildren.

"I really never met anyone like her in my life," Burnes added. "She was kind of the glue that held the family together."

— Ken Picard

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.