- Luke Eastman

Nadav Mille faced a difficult choice when he got a break from being questioned as a prospective juror a Newport courthouse last February. He and others in the jury pool were being asked hypothetical questions about child molestation. Mille, who has post-traumatic stress disorder, felt a growing sense of dread and said he needed a place to smoke the medical marijuana he uses to stave off panic attacks.

But Vermont law bans all public consumption of marijuana — medical and recreational — and Mille lived 40 minutes away, in Craftsbury. He didn't know anyone in town, and his only private space was his car. Smoking there, he feared, could lead to more serious trouble.

"It was either freaking out and having a panic attack, getting a DUI, or getting a ticket for smoking in public," Mille recalled in an interview last week. "The lesser of all those evils was getting a ticket for smoking in public."

He tried to find a quiet, out-of-the-way spot near the courthouse on Main Street, then he lit up a spliff — pot mixed with tobacco, meant to mask the odor of weed. And later, during a lunch break, Mille went outside to light up again.

That's when Newport Det. Nick Rivers walked up and wrote him a ticket for public consumption of marijuana, a civil offense that carries a $100 fine.

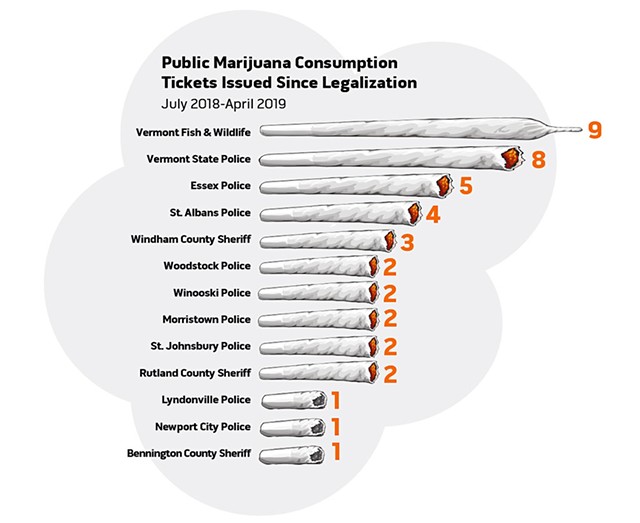

The ticket was one of 42 that Vermont police have issued since July 1, 2018, the day that Act 86 went into effect. The law legalized recreational possession and cultivation of cannabis. But it also made public consumption a civil offense. It didn't take long for someone to violate the prohibition: A game warden issued the first ticket the very day the law took effect.

Cannabis advocates have differing views on public consumption restrictions. Some consider them a political necessity as marijuana laws evolve. Others believe cases such as Mille's highlight the absurdity of bans. But to cops, the law is the law, even if that means writing a ticket to someone who is on the medical marijuana registry.

"Just because you have a card doesn't mean you could do that anywhere," Rivers said in an interview last week.

Before Act 86 went into effect, someone caught smoking in public would likely have been ticketed for misdemeanor marijuana possession, according to Tim Fair, a lawyer at Vermont Cannabis Solutions. He agrees that the law should limit where people can smoke pot. But he said Mille's situation shows why the complete ban on public consumption is a concern, especially for medical users.

"Can you think of any other patient taking any other medication that would be subject to this type of potential criminal liability, civil liability — liability, period — just for trying to take his medication?" Fair said. "It just makes absolutely no sense."

Vermont officials don't need to look far to find a more sensible policy, Fair opined. Québec allows cannabis consumption in the same places cigarette smoking is permitted, though municipalities can ban it.

According to data from the Vermont Judicial Bureau, which handles civil offenses such as speeding tickets, police issued 25 public consumption tickets during the second half of 2018, and 17 more during the first four months of 2019.

Local police wrote 19 of the 42 tickets. County sheriffs' departments wrote six; the Vermont State Police doled out eight. Another statewide agency was responsible for more tickets than any division of law enforcement: the Department of Fish & Wildlife, which issued nine.

Senior Game Warden Robert Currier said that makes sense. He and other wardens spend a lot of their time in rural places where people "more readily" smoke in public.

"We're not out specifically looking for marijuana consumption violations," he said. "We usually encounter it in addition to our duty as game wardens. Most of the times that we're issuing a ticket would be when there's other people around, to include children."

As state pot laws become more permissive, some wonder why the cops bother.

"Isn't there anything better that the Newport police have to do with their time except come look for someone who's smoking pot on the street?" Mille said.

Sen. Dick Sears (D-Bennington) chairs the Senate Judiciary Committee, which had a major role in shaping the 2018 legislation. He said the ban on public consumption was aimed at disruptive behavior.

"What we were trying to stop was people congregating outside in a public place and numbers of people smoking pot, like back when they used to have April 20th at UVM," he said of the notorious annual celebration at Vermont's state university.

The majority of the citations for public smoking have been one-offs — a single ticket instead of a number of fines at once. The busiest day was August 22, 2018, when, according to Capt. Ron Hoague, Essex police came upon a quartet of toking minors and issued four public consumption tickets.

Not every citation went to someone caught in the act. Fair represents Tyler Pelican, 25, who was ticketed last October by a cop in St. Albans for allegedly puffing pot in a car. Pelican claims he merely had a pipe that smelled like weed and hadn't actually toked in the vehicle.

Pelican is appealing a fine. Fair said he hopes the case will go to a jury of a dozen Vermonters who might see things differently.

"Most people are understanding. It is unfortunately a reality that not all [are]," Fair said, adding that police are "among the least empathetic" when it comes to cannabis.

Pelican agrees.

"I think people are being taken advantage of," he said. Instead of officers using their discretion to apply the law reasonably, Pelican thinks some are "going to try to give every ticket possible."

Matt Simon, the New England political director for the pro-pot Marijuana Policy Project, takes a wider view. He said his group understands the need for civil fines for public smoking as "a political compromise."

"A lot of people are deeply opposed to marijuana use, don't want to see it, don't want to smell it," he said, "... so having a fine to deter that in most cases gets people not to do it in public."

But Simon also recognizes the awkward situations that people such as Mille face.

"At the same time, where do they go?" Simon said. "It's now legal to consume."

Mille wonders the same thing. He said his situation went bad well before he lit up.

As soon as he was summoned for jury duty, Mille explained on a court questionnaire that he has PTSD. He was born in the U.S. but raised in Israel, where he served as a soldier of the Israeli Defense Force and, later, as a cop in Jerusalem. He quit the police force soon after he found a severed finger with a wedding ring on it at the scene of a bombing.

He later moved with his family to New York State so he could train to become a chef at the Culinary Institute of America.

"Whatever sanity I had left, I tried to preserve," he said.

Mille worried that hearing about violence or sexual abuse could cause a mental health crisis, and he asked repeatedly to be relieved.

"I was denied. So it was my civic duty; I went," he said.

At the courthouse, he told attorneys repeatedly that he would "absolutely not" be able to remain objective as a juror. The idea of sitting through a trial about something such as child abuse was overwhelming to him. Still, Mille was asked to stay.

As he returned from the lunch break on his third day in the jury pool, ticket in hand, a bailiff approached Mille and told him that lawyers had asked that he be excused — not owing to his medical concerns but because he got caught smoking weed.

Comments (13)

Showing 1-13 of 13

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.