Later this month, the Burlington City Council will debate the most substantial rezoning proposal the city has seen in 30 years.

If approved, the BTV Neighborhood Code would allow people to build multifamily homes where they're currently banned — including in their own backyards. Buildings would be allowed to take up a greater portion of a lot and, in some cases, could be taller.

Over the next decade, such infill development might create hundreds of homes in Burlington, where the demand for housing outruns the supply and the rental vacancy rate is less than 1 percent. But the proposal is getting pushback from residents who fear that denser development would eat up green space and overcrowd neighborhoods, particularly those already packed with college students.

City councilors seem to be listening. Last week, two councilors introduced amendments to make the changes more palatable. They'll debate the whole package on March 25, a week before a new mayor and handful of city councilors take office.

Outgoing Mayor Miro Weinberger, who championed the Neighborhood Code as part of a 10-point housing plan, hopes the proposal passes. The new zoning, he said, would reverse decades of constrictive housing policy.

"Name a Vermont problem, and housing is the solution," he told Seven Days. "Every neighborhood needs to be part of the solution."

Burlington's first zoning ordinance, adopted in 1947, allowed any type of housing to be built anywhere. That changed in the 1970s, when most residential streets were effectively limited to single-family homes and duplexes. In the 1990s, regulations became even more restrictive: Many neighborhoods were zoned for low density, and duplexes were banned in those areas. Minimum lot sizes got bigger, discouraging dense development.

Some of those rules have been repealed, but they've had lasting effects. In some neighborhoods, a single home occupies a large lot that has room for additional buildings. City officials say space on existing lots could be filled with housing types that Burlington lacks, including what are known as "missing middle" homes, such as triplexes and townhomes.

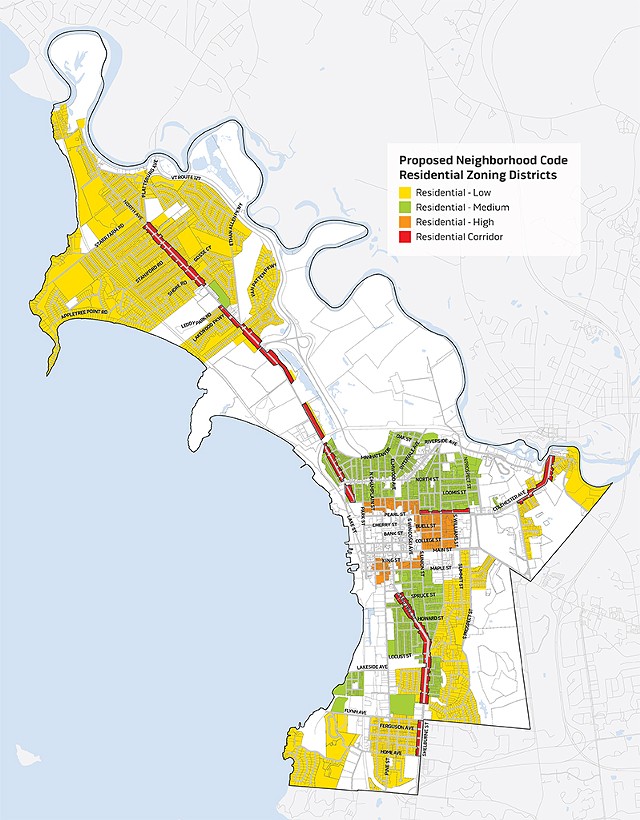

The Neighborhood Code "upzones" every area of the city — that is, it allows for denser development — including the 70 percent of residential lots that are now zoned for low density: the New North End, a good portion of the South End, and a chunk of what's known as the Old East End around East Avenue and Chase and Grove streets.

The proposed code would permit buildings to take up 45 percent of a lot in areas zoned for low density, compared to the 35 percent allowed now. In medium-density-zoned areas such as parts of the Old North End, allowable lot coverage would increase from 40 to 60 percent. In newly created "residential corridors" — swaths along traffic-heavy Shelburne Street, North Avenue and Pearl Street — a single building could occupy up to 80 percent of its lot, with no limit on the number of units.

Many Burlington lots have long, narrow backyards, thanks to strict "rear setback" standards. The new rules would shrink those setbacks, making it possible in some cases to add another building on the property. In a section of downtown that would be rezoned, buildings could grow from three stories to four.

But the change that's caused the most consternation is one that would allow two separate structures to occupy the same lot — a development pattern now largely banned everywhere in the city. On low- and medium-density lots, current zoning allows for single-family homes and, in some cases, duplexes. Under the proposed Neighborhood Code, two buildings with a max of four units apiece could be built on a low-density lot. Same for a medium-zoned lot, but with 10 total units instead of eight.

In other words, even what's considered low density now would become a whole lot denser. Five neighborhoods would go from the old low density to the new medium density — a "double upzoning" that some residents say goes too far.

That includes the Ward 1 neighborhood bounded by Mansfield Avenue and Pearl, North Willard, and Archibald streets, an area heavily populated by University of Vermont students but also a significant number of single-family homes. Homeowners fear that developers would scoop up those properties, raze the homes and build large student apartment buildings, further disrupting the balance of transient undergrads to long-term residents. They argue that their neighborhood is more vulnerable to overcrowding than the other areas that would move from low to medium density, all of them in the South End: Five Sisters, Lakeside, and the areas around Hoover and Clymer streets and South Union to South Willard.

Ward 1 residents have voiced their displeasure on Front Porch Forum, in letters to the editor and at city council meetings. They've labeled the proposal "frightening," "draconian" and "dystopian" — characterizations that proponents say amount to NIMBYism.

Sharon Bushor, a former longtime city councilor in Ward 1, says squeezing eight units into backyards is too much anywhere, not just in her neighborhood. She worries that losing backyards to buildings will worsen stormwater runoff and aggravate climate change.

The proposed Neighborhood Code isn't about the "missing middle," Bushor said. "This is density at all costs."

City planners disagree. Graphics generated by the department show that most of the lots in the Ward 1 neighborhood — and in every other area slated for a similar change — already exceed today's low-density standards. About a third of the lots in the Ward 1 area would still be more densely developed than the new standards would allow.

That's not really "double upzoning," as some critics assert, Burlington planning director Meagan Tuttle said.

"It's about better aligning zoning with what has existed," she said. "We were trying to recognize how the Neighborhood Code could be implemented given those existing patterns."

Nonetheless, councilors have introduced amendments to address the Ward 1 concerns. Outgoing Councilor Zoraya Hightower (P-Ward 1) has proposed slightly reducing the amount of land that buildings could occupy, leaving more room for green space, and cutting the allowable total units from 10 to eight. Councilor Tim Doherty (D-East District) wants the area zoned for low density instead of medium.

Councilor Melo Grant (P-Central District), meantime, thinks every neighborhood should be upzoned to medium. Under the current proposal, the wealthier, whiter areas of the city — the Hill Section and New North and South Ends — would be zoned for low density whereas the poorer, more racially diverse Old North End would be zoned for medium.

Using medium density as a baseline would not only address equity issues, it would create more housing, Grant said.

"Do we want to be a city or not?" she asked. "There are people that are prepared for that, and there are people that are not."

None of the councilors' amendments would appease Paul Bierman, a Ward 1 resident and UVM environmental science professor. First, he thinks Burlington should be building up, not out. And he thinks the city needs to rein in the student housing problem before adopting zoning that could worsen it. The city is negotiating a deal with UVM under which the university would build up to 1,500 new student beds on three campus lots. The city, in turn, would modify zoning to make the build-out possible. Councilors have raised concerns about the proposal and haven't scheduled a vote on it.

Bierman says Burlington should take the time to get the rezoning right.

"We can have an urban core that is both high density, offers affordable housing to those who need it and still protects our environment," he said. "There's no reason to hurry."

Ashton MacKenzie, however, feels a sense of urgency. The New North End resident shares a small townhome with two other people and would consider buying a triplex if one were available — and legal to build. The Neighborhood Code would create more of those housing options, MacKenzie said, freeing up his townhouse for one of the many people who want to live in Burlington but can't find a place.

"There's so much need for housing in Burlington," he said. "It's ridiculous that we have this situation where you literally can't build anything, anywhere."

Of course, the code's success would depend on whether people could afford to use it. Developing a new apartment building, especially on a smaller scale, is costly, from the permits to the lumber and labor, both of which are more expensive these days. That's why Weinberger thinks the change would be more gradual and perhaps not as dramatic as some residents think.

He compared the Neighborhood Code to the city's recent rezoning to encourage the building of accessory dwelling units — tiny homes that people add to their property to rent out or use as "mother-in-law" apartments. Burlington permitted an annual average of three ADUs in the 16 years before the reform passed in 2019. Since then, an average of 13 have popped up each year. Similar reforms in California have been so effective that ADUs now comprise one of every six new housing units permitted in the state.

Weinberger thinks the Neighborhood Code could play out in a similar fashion.

He predicted, "People are going to figure it out over time."

Correction, March 7, 2024: An earlier version of this story inaccurately described the number of units that would be allowed in a low-density district. It also misstated what part of the proposal councilors delayed voting on.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.