- Matthew Thorsen

- Christine Kemp Longmore (Offender Workforce Development Program), Gary De Carolis (Turning Point Center of Chittenden County), Alicia Sherman (Aspenti Health), Chris Powell (Aspenti Health), Amy Boyd Austin (Catamount Recovery Program)

But at 13, she hurt her knee. After surgery, her doctor prescribed Percocet to help relieve the pain. It was her introduction to opiates. For the first time, she experienced a kind of numbness — what she now calls “the feeling of being outside of yourself.” She liked it.

- Matthew Thorsen

- Alicia Sherman, Aspenti Health

“I wasn’t able to be a good friend,” she says of those years. “I wasn’t able to be a good daughter. I wasn’t able to show up for life.”

When she was 28, Sherman came down with Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, a deadly, antibiotic-resistant infection related to her IV drug use. It’s not an exaggeration to say that it saved her life.

“I didn’t mean to get sober,” she remembers. But treating MRSA requires a lengthy hospital stay. Sherman was in the hospital for three months, during which she got clean and resolved to stay that way.

Fast-forward four years: Sherman has turned her life around. Today she owns a house, a car and “two amazing dogs.” On September 5, she celebrated her fourth year of sobriety. A few days later, she got married. “September is a good month,” she says with a smile.

It also happens to be National Recovery Month — a time dedicated to celebrating and supporting people, like Sherman, who are in recovery from substance use disorder.

“People have this idea that we’re under the bridge,” she says, “drinking out of paper bags.”

“We’re real people,” she says with conviction. “We do recover.”

It’s a message that resonates now more than ever. It seems nearly everyone has a connection to someone — a friend, neighbor, family member, classmate or coworker — who’s struggling with substance use disorder. Often, as in Sherman’s case, it starts with prescription painkillers.

Not all of these stories have happy endings. Across the country, drug-related deaths are on the rise. In 2016, about 64,000 people in the U.S. died from drug overdoses — now the number-one cause of death for Americans under 50. The rise in overdoses related to heroin and other opioids such as fentanyl and oxycodone is fueling the trend. In August, President Donald Trump declared the opiate crisis a national emergency.

Helping drug users get and stay clean has become an urgent national priority. Sherman is involved in that effort now, too, through her employer, Aspenti Health.

Simply put, Aspenti is a Burlington-based drug-testing company, but its commitment to helping those in recovery extends far beyond the bottom line. Aspenti doesn’t just provide state-of-the-art clinical testing — the company also encourages, supports and employs people in recovery, like Sherman. And it’s creating new public-private partnerships to address the opiate crisis.

- Matthew Thorsen

- Chris Powell, Aspenti Health

Powell came to Aspenti after being CEO of a health care technology company. Before that, he worked as a vice president of sales and marketing for GE Healthcare, and, before that, its local predecessor, IDX Systems. Gregarious and ambitious, Powell says he was drawn to Aspenti because it presented a chance to “make a real difference” in a “massive epidemic.”

As a testing company, Aspenti interacts with three different but important groups: health care providers who request drug tests; insurance companies that pay for them, and the patients who take them. “We touch all three,” Powell notes. The company can educate, collaborate and affect change with them all. Aspenti works closely with providers to understand the results of the drug screens, and is leveraging drug collection data in new ways to help providers improve patient care.

In honor of National Recovery Month, Aspenti is leading a larger community effort to fight the stigma attached to substance use disorder. This initiative includes “The Change Corridor,” a recovery-themed exhibit at Burlington International Airport that aims to reframe the discussion around substance use disorder in Vermont.

Designed in close partnership with local leaders on the front lines of the opioid epidemic, The Change Corridor will address the roots of opioid addiction — a disease that hijacks the brain, not a lifestyle choice. It will build compassion for those with opioid use disorder, which affects every neighborhood, community and income level. It will challenge people to think about their own biases, and The Change Corridor will leave those who experience it willing to learn more.

Can’t make it to the airport? Read on to learn more about a few of Aspenti’s community partners. Aspenti is shining a light on them in hopes their stories will inspire others to pitch in and get involved.

The ‘Air-Traffic Controller’

Technically, Alicia Sherman’s job title at Aspenti is “strategic client advisor.” Practically, she says she’s more like an “air-traffic controller.” She communicates with numerous providers, insurers and patients on a daily basis and helps guide them through Aspenti’s process.The word “strategic” in Sherman’s title is an indication that she’s managing some of the company’s most valuable accounts and relationships, according to Aimee Marti, vice president of branding and corporate social responsibility.

It’s a role for which Sherman says she feels “uniquely qualified,” because she has “a deep understanding of the patient population and how best to serve them.”

It’s hard to believe that, just a few years ago, she couldn’t find anyone to hire her.

When she got out of the hospital after battling the MRSA infection, Sherman got a room at the Oxford House, a sober living group home in Burlington. “I moved in with two plastic bags full of my stuff,” she remembers.

To stay, she had to find a job — within two weeks. “I hit the streets of Burlington, looking,” she says. But once she checked the box on applications indicating she’d been arrested, no one would even give her an interview; her job search happened before July 1, 2017, when it became illegal for Vermont employers to request this information on applications. Finally, Sherman lied about her criminal past and landed a retail job, which she kept for a year.

Then she applied at the drug-testing company that is now Aspenti. “I was honest,” she says. “I told them, ‘I have a past.’ They met me face-to-face and met me as a person.”

In 2014, Sherman was hired as an account manager. She’s since been promoted a few times to her current role — a rewarding job that she loves. “Access to meaningful employment can save lives,” she says.

Over the years, she’s assisted others in recovery in various ways: by volunteering as a mentor at Oxford House and serving as the chairperson of the Step Into Action Recovery Walk from 2014 to 2016. Lately, she’s been speaking publicly about her past. She testified during an opiate-focused town-hall meeting in Burlington, which lead Mayor Miro Weinberger to cite her in his 2017 State of the City address. She spoke before the governor’s coordinating council on opiate abuse, and talked with national “drug czar” Richard Baum during his visit to Vermont in June.

Sherman says speaking out about her recovery is not part of her job at Aspenti. “I do it because I think it’s the right thing to do,” she says. “I want people to see me and say, ‘If she can do it, I can do it.’”

Advocating for Offenders

- Matthew Thorsen

- Christine Kemp Longmore, Offender Workforce Development

Working out of the Community Justice Center at the city's Community and Economic Development Office, she’d be helping convicted criminals get hired after their release from prison.

You’ve got to be kidding me, she remembers thinking on the way home from the interview. That’s a hard sell.

But she was up for the challenge. When the job offer came, she took it.

Twelve years later, she’s still at. “It’s really satisfying,” says Longmore, who is technically a contracted employee of the Vermont Association of Business Industry and Rehabilitation who works at the CJC. It’s expensive to incarcerate people, she notes, and newly employed workers contribute to the economy when they’re earning money and paying taxes. If she finds jobs for two offenders a month, she essentially covers the cost of her salary.

The majority of Longmore’s clients have done time for drug-related offenses, whether possession, distribution or property crimes driven by addiction. She doesn’t keep hard data but estimates that number is “exponentially higher” now than it was when she started her job.

Putting these individuals to work doesn’t just make economic sense — it helps them stay clean and stay out of jail. “A lot of free time is not good,” she observes. And, “if they have a job, then they have something to lose.

Longmore meets with offenders as a group on Tuesdays, conducting mock interviews and giving job search tips. She also coaches them one-on-one and teaches them to advocate for themselves. Though she’s small in stature — whippet thin and just over five feet tall — she’s feisty, funny and irresistibly enthusiastic.

Some clients are former drug dealers. She’s told a few of them to “put on a shirt and tie and go down to the car dealerships on Shelburne Road,” she says. At least three of those followed her advice to full-time employment.

“I tell them, ‘Listen, you’re a salesperson,’” she explains. “People laugh when I say that, but it’s true! It’s such a transferrable skill.”

Over the years, Longmore has developed relationships with hundreds of area employers. She says most have become more willing to hire recently released offenders. She attributes that, in part, to a shortage of workers, though she’s also noticed employers are more willing to accommodate employees in recovery — for example, allowing them to leave work to get methadone or suboxone treatments.

More than a year ago, she placed a client with a heroin addiction at a local grocery store. When he relapsed and enrolled in a residential treatment program, management treated it as a medical leave. “I was like, oh my god, if we could get employers to do that, it would be a total game changer,” she gushes.

The employee returned after a stint in rehab. He did eventually leave his job, but, she says, “he left appropriately” and can still use his supervisor as a reference.

“Professionally,” she says, “it was a huge win.”

Longmore has gotten more involved with criminal justice issues. She’s now the chair of the Burlington Police Commission and serves on both the Vermont State Police Fair and Impartial Policing Committee and the Vermont Attorney General’s Racial Disparities in the Criminal Justice System panel.

She hasn’t worked with Aspenti much, but Longmore is “very encouraged” by the company’s commitment to de-stigmatizing recovery and substance use disorder.

Her motivation is not just professional.

Two years ago, a drug overdose claimed a young man who was “like a stepson” to Longmore. She was with him when he died. "He was in my arms at one point, because we were trying to help him breathe," she recalls. “It was the most horrible experience. To have that happen up close and personal like that was pretty devastating.” He was an athlete, she says, good-looking and funny. “It was a really scary thing to see all these young people mourning this 21-year-old kid.”

She pauses, then adds: “We have to figure out a way to get everybody mobilized.”

“A Port in the Storm”

- Matthew Thorsen

- Gary De Carolis, Turning Point Center of Chittenden County

“And,” he adds, “we’ll help you get the job.”

Turning Point is a downtown recovery center located just steps from the Church Street Marketplace in Burlington — it’s one of 12 nonprofit Turning Point centers in Vermont. This safe, clean space dedicated to sober living is open to the public from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. every single day of the year, including holidays. “Those days when people are very susceptible to relapse and are down, we’re open,” explains De Carolis.

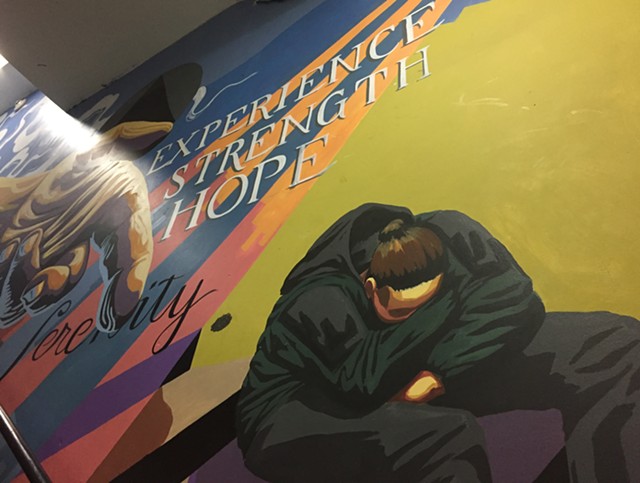

Visitors — De Carolis calls them “guests” — access the center through a street-level entrance, then climb a flight of stairs to reach the second-floor center. A mural greets guests in the stairwell: It depicts a person dressed in gray slouching dejectedly, arms crossed, head down. On an adjacent wall, in elegant script, are the words “You are no longer alone.”

- Don Eggert

- The stairway mural at The Turning Point Center of Chittenden County

All of the center’s volunteers, peer support workers and operations staff are in recovery — except De Carolis. He ended up at Turning Point almost by accident.

A New Jersey native, De Carolis came to Vermont in the 1970s after graduating from Kean University with a bachelor of arts in social welfare. After earning a master’s degree in counseling from the University of Vermont, he gravitated to government and policy work: He served as a Burlington city counselor from 1981 to 1987 and worked for the state’s Department of Developmental Disabilities and Mental Health, eventually rising to deputy commissioner. Then he moved to Washington, D.C., where he spent nearly a decade overseeing child and adolescent mental health programs for the U.S. Department of Health. He returned to Vermont in 2002, to work as a leadership consultant. Five years ago, he started a side business giving Burlington history tours.

Around that time, a Turning Point board member called De Carolis and asked him to fill in as interim executive director while the board searched for a new leader.

De Carolis says he knew almost immediately that he wanted the job himself. “When I walked through the door,” he remembers, “I could see this place saved lives, helped people rebuild their lives, gave people hope who had lost hope.”

When he first arrived at the center, he recalls, some guests were using drugs in the stairwell and in the bathrooms. “It was not a safe place,” he says. Since then, he’s kicked out guests who were using, stabilized the center financially, and added programs. New traffic and usage data shows roughly 2,500 visits a month. Roughly 65 percent of Turning Point guests are in their first year of recovery. Half of guests identify alcohol as their “drug of choice;” for the other half, it’s heroin.

De Carolis also surveyed guests about their biggest concerns, aside from substance use. The top three? Anxiety, depression and oral health. He used that information to get a dentist to visit the center four times a year.

His latest project is a capital campaign. Turning Point hopes to raise $500,000 for a down payment on a new, larger downtown space — a professional-looking brochure outlines plans for a place with multiple meeting spaces, a fitness room and a dedicated area for moms and infants. Along with statistics, the pamphlet includes guest testimonials. “The Turning Point Center is a ‘port in the storm’ for many of us,” writes guest Jim W., “a place to congregate, share, heal, learn and laugh.”

Below the quote are dozens of cardboard houses, representing Turning Point’s hoped-for new home — guests have decorated them with stars, flowers, rainbows and, occasionally, words. “Love, Hope, Dream, Recovery,” reads one.

Says De Carolis: “These are amazing people who walk through this door.”

Majoring in Recovery

- Matthew Thorsen

- Amy Boyd Austin, Catamount Recovery Program

Generally, she says, college students in recovery “feel absolutely invisible and not valued.”

Austin is working to change that. She started the Catamount Recovery Program seven years ago, after several years working with UVM’s Office of Health Promotion. Funded by a student health fee, CRP offers yoga classes, a weekly lunch gathering, sober social activities and drop-in hours when students can just hang out in a substance-free space. Austin also organizes field trips, and plans events around “traditional drinking times,” she says. Think sober Super Bowl Party. Students also agree to take a one-credit class for two semesters, as an orientation to the recovery community.

CRP doesn’t yet have its own space — Austin works out of a cubicle in the Living Well office on the first floor of the Davis Student Center. It holds meetings, events and drop-in hours in an adjacent studio space that the group shares with other Living Well programs. UVM offers substance-free housing on its Trinity campus.

In CRP’s first year, Austin worked with five students. Last year, that number had grown to between 25 and 30. About 60 percent had had experience with opiates.

The growth in participation doesn’t necessarily indicate that more students are using, Austin says; it means that more of them are finding their way to recovery. Due to the stigma associated with substance use disorders, and even recovery, some students receive numerous referrals over multiple years before seeking help.

“I think a lot of students white-knuckle it through abstinence,” she says — meaning they try to make it on their own, possibly afraid to admit their struggle, or unaware that there is a community of support available.

The ones who make it into the group tend to perform as well or better than the average UVM student, Austin notes. A flyer advertising the program points out that group members maintain an average GPA of 3.3 and a 92 percent graduation rate.

A quote from an anonymous student sums up the group’s appeal: “Without the CRP I never would have stayed sober or stayed in school. It provided recovery support and a sense of community that saved my life.”

“The students who are working a program of recovery are some of the most amazing students on this campus,” says the CRP director.

Austin herself is exceptional. Though CRP is the only campus recovery program in Vermont, there are 150 of them around the country. They all belong to a national association; Austin is currently serving a term as the organization's president. In 2016, she received its lifetime achievement award for “exceptional commitment to advancing collegiate recovery.”

It's work she finds rewarding — in part because Austin knows her efforts are helping her students succeed in their struggles with substance use disorder. "It is surmountable," she insists.

And watching them make progress, she says, "is a privilege."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.