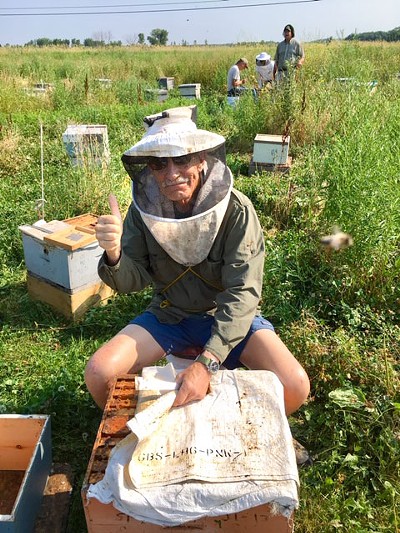

- Caleb Kenna

- Andrew Munkres inspecting a hive at Lemon Fair Honeyworks in Cornwall, Vt.

Shortly after the sun begins to rise in Cornwall, the bees get to work. Thousands of them exit the apiary at Lemon Fair Honeyworks and pass the electric fence that keeps out bears. Then they fly across the landscape and harvest nectar and pollen from a variety of trees and wildflowers.

The bees return to the hive with glistening stomachs full of nectar and balls of pollen attached to their tiny thighs like bright yellow saddlebags. Their hard work fills the boxes in the apiary with hundreds of pounds of golden honey — far more than they would be able to consume themselves.

That’s where Lemon Fair owner Andrew Munkres comes in.

Munkres became interested in beekeeping 20 years ago, after he stopped raising livestock on his farm. Now he has more bees in his apiary than there are people in the state of Vermont.

When he goes out to check on the bees wearing his veil and coveralls, Munkres blows smoke into the hives to dilute the scent of pheromones, the substance bees excrete to communicate danger. Then he lifts a box that looks like a filing cabinet with a beehive inside.

- © Lkordela | Dreamstime

- A honey bee showing pollen collected on its hind legs, perched on a blue aster

Extremely comfortable around the bees despite getting stung nearly every day, he brushes a few of them away with his bare hands. Munkres reaches in to pick up one of the bees lightly between his fingers as calmly as moviegoers grab popcorn out of a bucket. “See that, there?” he says, exposing the underside of the bee’s abdomen. “Inside is the honey stomach. It’s like a second stomach where they can store nectar.”

After returning the bee to the hive, Munkres swipes a tool that resembles a palette knife across the top of a waxy, sealed honeycomb. Dark gold liquid oozes out of the box, ready to eat. The fresh honey is chewy — it still contains bits of raw honeycomb. It’s full of strong, sweet flavor and much richer than any clear-colored generic brand you’d buy at the grocery store.

Munkres is one of Vermont’s 15 full-time beekeepers, or apiculturists. The state is also home to hundreds of part-timers and hobbyists. They’re part of a sweet beekeeping tradition that dates to the 18th century.

- Caleb Kenna

- Andrew Munkres, owner of Lemon Fair Honeyworks in Cornwall, Vt.

Vermont’s apiculturists have worked hand in hand with the dairy industry and helped pollinate the variety of flora and vegetation across the Green Mountain State. Laura Johnson, a pollinator specialist with the University of Vermont, said the beekeeping community is an important part of local agriculture. “We live in such a small state, and there’s a small community, but there’s an amazing level of pride in the production of Vermont honey,” she said.

It frequently wins worldwide awards and is known for its unique multifloral flavors from plants grown on the rich soil of the Champlain Valley.

Beekeeper James Key of Stockbridge has won some of those awards. “When people eat Vermont honey, they have no words to describe it. It’s the best they’ve ever had,” he said.

Unique to Vermont

- Courtesy

- Laura Johnson harvesting honey

Johnson’s interest in honeybees came from her childhood in Vermont's Upper Valley. Beekeeping was her mom’s favorite hobby; she’d spend many hours in the yard with her boxes of bees. Johnson didn’t think about bees in the context of her own career until she started working for the Peace Corps. She lived on a farm in Paraguay, where she worked with honeybees.

“I always had a lot of different types of interactions with the honeybee world,” she said. “But actually working with them day in and day out like that made me think about it differently.” After that experience, she went to New Mexico State University, where she got a degree in horticulture.

When she returned to Vermont, Johnson started keeping bees of her own and selling honey on a small scale to a farm stand. She calls herself a “hobby beekeeper.”

In her role at UVM, Johnson provides technical assistance and applied research in partnership with Vermont farms and consults with them about when, where and what to plant to support pollination. She also monitors blooms on farms around the state and facilitates relationships between the bees and Vermont farms and orchards.

“It’s a great opportunity for beekeepers during apple bloom, which feeds the bees, and the orchards benefit from having honeybees working the blossoms to ensure good yields and a good crop,” she said.

Johnson said something that makes Vermont unique is the natural diversity of the landscape. “We have flatland, hilly land and mountainous land,” she said. “This creates a variability in types of flowers, which you can taste in the honey crop.”

- Sergey Kolesnikov | Dreamstime

Buying local honey, Johnson said, directly contributes to Vermont’s economy and the success of its agriculture.

“When you buy local honey, you get to taste Vermont's unique floral resources,” she explained, adding that a lot of store-bought honey comes from bees that harvest nectar from a single crop. Another point of difference is that many local beekeepers do not heat their honey before sale, which preserves both flavor and enzymes that are believed to be good for the immune system. “There is something to be said about the diversity of our honey’s flavor profile,” she said. “It’s beneficial on many levels.”

A Growing Community

- Courtesy

- Bill Mares catching queen bees

Burlington beekeeper Bill Mares refers to Vermont as "the land of milk and honey.” In fact, that’s the title of the book that he and his friend, fellow beekeeper Ross Conrad, wrote about the history of beekeeping in Vermont. The book chronicles the state’s apicultural tradition, including both struggles and achievements.

According to Mares, Vermont’s principal dairy farming area is also its primary beekeeping area — Addison County. To produce forage to feed the cattle, you need pollination from bees, and those bees need the nectar. It’s a symbiotic relationship.

“Without the pastures and open fields for farms, the bees wouldn’t have the forage to make honey,” said Munkres.

Mares started beekeeping 50 years ago. “I tried a lot of hobbies, and this was the one that stuck,” he said. Since then, he’s taught classes, written two books, and served as the president of the Vermont Beekeepers Association.

Initially formed as the Champlain Valley Beekeepers Association in 1875, the group changed its name to the Vermont Beekeepers Association in 1886. Since then, it has grown into a community of more than 500 beekeepers. It offers educational opportunities, camaraderie, and a forum to air issues and challenges.

It’s a bigger group today than it was when Mares joined, in 1980. “It’s grown from a village to a metropolis,” he said.

Mares has taught classes at his apiary in Burlington’s Intervale, and he and others have taught more than 1,000 prospective beekeepers in the ACCESS program at Champlain Valley Union High School in Hinesburg.

The association always welcomes new members. The way Mares sees it, beekeeping is as essential and unique to Vermont as cheese or dairy production.

“One of the things that’s special about Vermont honey is the variety of nectars that get mixed into it,” Mares explained. “It’s not a single flavor. People can even taste a difference between Addison County and Chittenden County because we have different floral sources other states don’t have. That kind of variety is pretty incredible for such a small state.”

A Delicious, Award-Winning Crop

- Courtesy

- Shots from James Key's Instagram account

The Center for Honeybee Research's Black Jar Honey Contest is a big deal. It’s the largest contest of its kind in the world, and the judges spend months deliberating over honey from across the globe. Vermont honey has made the cut on more than one occasion: In 2022, Worcester's Rick and Genevieve Drutchas won the grand prize, and this year James Key was a finalist.

Key started thinking about keeping bees on his Westford farm six years ago for a simple reason: “I wasn’t seeing any bees in my garden,” he said.

Key, who has since moved to Stockbridge, attended the Northeast Organic Farming Association conference at UVM in 2017, where he met Conrad, who agreed to be his mentor. Key then enrolled in classes and bought his first hive from Munkres.

As Vermont’s first Black beekeeper, Key said, “It’s pretty nice to make history.” He relishes the challenge of maintaining his hives. Key relies on Mother Nature rather than anything synthetic to take care of his bees, which he said is a big part of his practice. For example, he grows plants with certain medicinal values for the bees to pollinate, hoping to find natural ways to keep out one of the biggest pests — the varroa mite.

- Courtesy

- Rick Drutchas inspecting colonies of honeybees in Worcester

Drutchas has been a beekeeper since 1973. He’s developed a reputation over the years; it’s not unusual for people to knock on the door of his Worcester home, looking to purchase his honey.

Drutchas got into the field on a whim. When a friend was unable to take care of his hives, Drutchas took over. What started as a curiosity became a lifelong occupation.

“It was something I discovered I could do,” he said. “I was pretty successful, so I just stuck with it. And it’s always interesting. You never stop learning, and you’re looking at flowers all the time. What could be so bad about that?”

Drutchas has helped farmers and growers throughout the state by pollinating apple orchards and pumpkin patches, as well as clover and hay crops for dairy farmers. “Farmers like to have bees around,” he said.

Beekeeping has taken Drutchas across the country. He worked with a bee breeder in Alabama for a few years before returning to Vermont to take a position as the state apiculturist. After 10 years of working for the state, he bought a friend’s full-time operation, spending his days outdoors at Bee Haven Honey Farm, where he works with his wife, Genevieve. These days, Drutchas has cut back to part time.

He said the secret to his award-winning product comes from the land he harvests it from. “We have a bunch of sweet Champlain Valley soil, and that makes for some really nice flowers and legumes, some of the really good honey-producing plants,” he explained. “I’ve now had honey from all over the world, and Vermont honey is just the best.”

To learn more about where to buy Vermont honey, visit vermonthoney.org.

Recipe: Honey Mustard Garlic Dressing

By Ross Conrad

- © Elena Veselova | Dreamstime

Heating honey changes its flavor, so to savor the delicate floral flavors of my honey, I prefer honey recipes that do not require cooking. Here is one for a honey mustard garlic salad dressing:

Ingredients:

- 1 tablespoon mustard

- 1 tablespoon honey

- 4 tablespoons apple cider vinegar

- 1 cup olive oil

- Garlic cloves, minced

Directions:

Mix mustard, honey and vinegar until fully combined. Slowly pour olive oil into the mixture while stirring. Continue pouring and stirring until the mixture emulsifies, changes texture and becomes uniform in appearance. Add as much minced garlic as you can stand. Taste is best if dressing is left to sit for at least half an hour before use.