- Courtesy Of Brian Jenkins/Beta Technologies

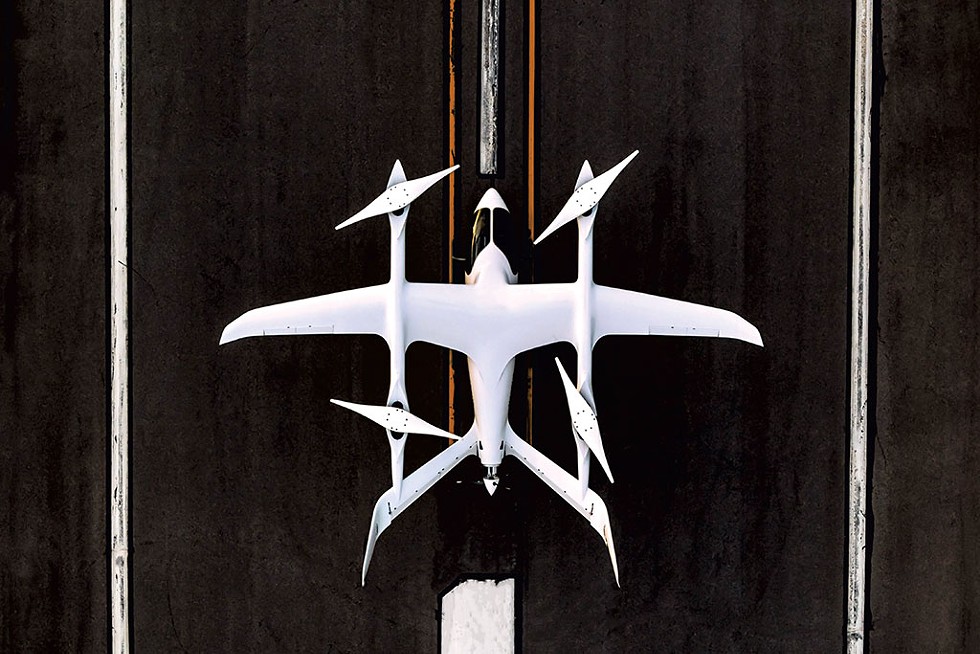

- The Alia aircraft

You can't not see the planes. Beta Technologies' two prized prototypes take up the center of its bustling headquarters inside a hangar at Burlington International Airport. Around the upper rim of the airy space, employee workstations overlook the lustrous white machines through long walls of glass. During a recent tour, a group of engineers studied aircraft designs on a projection screen in one conference room. Next door, two others played Ping-Pong.

The open office layout isn't to imitate Silicon Valley, or even to show off Beta's aircraft, founder and CEO Kyle Clark insisted. He thinks the glass helps get engineers talking to each other, which leads to a better plane. And Clark is obsessed with building a better plane.

The prototypes parked in the hangar are the first two iterations of Beta's latest, most promising design. With a 50-foot wingspan and a tall V-shaped tail, the aircraft dubbed Alia uses four propellers to lift like a drone and a fifth to fly forward like a plane. It's designed to carry six people or three pallets of cargo up to 250 miles, powered entirely by rechargeable electric batteries.

Alia represents an aviation breakthrough-in-waiting, physical evidence of how the far-off vision of flight without fossil fuel has become tantalizingly close.

For many, the nascent electric aviation field is synonymous with a fascination for flying cars. A new class of experimental aircraft called electric vertical takeoff and landing (eVTOL), which includes Alia, promises quiet, efficient propulsion and the nimbleness of a helicopter. Add in advances toward pilotless operation, and the aircraft could usher in radically different skyscapes and personal transportation networks, the thinking goes. Accordingly, Silicon Valley has jumped in to fuel a race to create the first big electric air taxi company.

Beta, homegrown in the less-vaunted Champlain Valley, has leapt toward the front of the pack by charting a different flight path. Since founding the startup in 2017, Clark has been focused not on the Jetsons but on the planet. The quickest way to begin moving air travel away from fossil fuels, Clark said at a recent conference, is to build "insanely reliable" aircraft that are capable of more straightforward uses, such as transporting cargo.

Much of the work to achieve that goal takes place in labs on the South Burlington hangar's first floor, where there's considerably less glass than the trendy office space above. Here, Beta's engineers continue to refine the cutting-edge electric motors and control systems they've been developing quietly for the last few years.

- Oliver Parini

- The hangar at Beta Technologies

Between an electronics lab and the 3D printing shop is a pair of rooms that Clark — a slightly scruffy, six-foot-six engineer, serial entrepreneur and former pro hockey draft pick — introduces with a mechanic's charm as the "torture chambers."

In these tiny thunderdomes, Beta's most precious components get stuffed into cages and pushed toward their breaking point. They're cooked and frozen and shocked with the same voltage as a lightning strike. They're also strapped to a vibration table and rattled according to computer-programmed frequencies, "maybe a Metallica song, or maybe an airplane vibration modal spectrum," Clark said. In separate containers on airport grounds, Beta's electric motors spin on 13 testing devices called dynamometers to gauge their durability.

"We just beat the shit out of motors continuously," Clark said.

The company's first-things-first approach is beginning to pay off. Since its unveiling last June, Alia has undertaken some of the most advanced flight testing in the industry and now regularly flies 100-mile practice routes over Chittenden County. Last week, the U.S. Air Force granted Alia approval to fly on behalf of the military, only the second electric aircraft authorized to do so.

In April, Beta signed a deal to sell at least 10 of its roughly $4 million aircraft to United Parcel Service by 2024; UPS says it will use them on some of its regional express delivery routes, flying packages between warehouses instead of airports. Beta's also committed to delivering up to 20 planes to Blade, a company that currently offers $800 helicopter rides from Manhattan to the Hamptons. Beta's workforce has grown from 75 employees a year ago to more than 230 and counting, as the company plans a big push toward flight certification and production.

On the cusp of pioneering commercial electric aviation, Beta could quickly become one of Vermont's largest companies if it can successfully compete in a new global market. Clark and his wife, Katie, met in middle school in Essex and dream of their community becoming a "green aviation stronghold." But the startup is far from alone in its quest, and its flurry of achievements comes as competitors have raked in gobs of investor cash — more than $4 billion in 2021 so far.

Beta raised $143 million in new private capital in March and was in the process of raising $190 million more, according to a U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission disclosure filed April 1 but unreported until now. Some industry analysts believe the cost to bring a new plane to market is even greater, but they nonetheless consider Beta a top contender because of its tangible progress in a speculative industry.

"It's a program that's more likely to make it than others," said Brian Foley, a longtime aerospace consultant, offering a levelheaded assessment. "But it's still, like many of them, somewhat precarious."

'You're On'

- Oliver Parini

- Kyle Clark

Clark, 41, has been imagining different ways of flying for a long time. As a senior at Harvard University in 2004, he exuded confidence when his thesis project was named best in his engineering class. The young airplane and motorcycle enthusiast built a flight simulator based on a motorcycle chassis that could more intuitively match the roll and pitch pilots experience while flying. "I have every intention of taking this project through to completion," he told the university's newswire, the Harvard Gazette.

By "completion," Clark meant producing a functional aircraft that the pilot can roll a sport bike into, use it to pilot the plane, and upon landing ride it out — in other words, a flying motorcycle. "The feasibility study is complete, and the concept is indeed realistic," he was quoted as saying.

The project didn't materialize, nor did his other ambition, professional hockey. The Washington Capitals drafted the Harvard winger in 1999. He played a couple of seasons on its minor league affiliates but proved a better enforcer than goal scorer.

The Clarks moved back to Vermont, where Kyle cofounded iTherm Technologies, a maker of induction heating power supplies, in Colchester. He sold the company to Dynapower in South Burlington and became that company's director of engineering, working on power electronics and battery systems. He and another Dynapower alum later started Designbook, now Venture.co, as a social networking and investment-seeking platform for tech entrepreneurs. Kyle's collegiate "cycleplane" concept resurfaced as the example he liked to use of a business venture that could benefit from Designbook.

In March 2017, Clark was giving a presentation on batteries for an aviation company in Philadelphia when someone in the audience stopped him. "Who are you, and why are you here?" Clark recalled being asked.

His interrogator was Martine Rothblatt, the author, entrepreneur and futurist who is one of the more interesting rich people in the world. Rothblatt, who has a home in Vermont, founded Sirius Satellite Radio and, after her daughter was diagnosed with pulmonary arterial hypertension, started the now-publicly traded biotechnology company United Therapeutics to cure her disease. As a trans woman, Rothblatt has advocated for the rights of trans and gender-nonconforming people. She and her wife, Bina Aspen, launched the Terasem Movement, a group of educational and religious organizations that seek to transplant human consciousness through technology and that operate out of Lincoln. One of Terasem's projects involved replicating Bina as an artificial intelligence robot named Bina48.

Rothblatt took note of Clark's enthusiasm and their shared Vermont ties and invited him for coffee the next time she was around. She wanted to know how he would go about developing an electric aircraft, Clark said.

Electric aviation was having a moment. In October 2016, the ride-hailing giant Uber issued a white paper that laid out a vision for a network of on-demand, pilotless electric air taxis within a decade. The small aircraft would be able to take off from and land on helipads atop buildings, shortening urban commutes.

Rothblatt, a helicopter pilot, was exploring electric flight, as well, but for her own reasons. She wanted a fleet of carbon-neutral aircraft that could transport the human organs that United Therapeutics hopes to manufacture before 2030. She'd worked with a team of California engineers in 2016 to test fly a conventional helicopter retrofitted with a rechargeable battery. That same year, United Therapeutics subsidiary Lung Biotechnology invested $10 million in a Chinese startup, EHang, that is developing eVTOL planes. But Rothblatt was still looking to place another bet. She was in Philadelphia that day, she told Seven Days, to hear from another company that was looking into the technology; Clark was there as one of its potential contractors.

"It's kind of my nature as a technologist to always have multiple shots on goal," she said.

Clark struck Rothblatt as having the "perfect mixture" of the skills she was looking for: "somebody who completely understands how to build and execute businesses for electric power," she recalled, "and somebody who is also a pilot and completely understands flying."

Their coffee date turned into a daylong visit and a request that Clark put some ideas in writing, he recalled. He returned to his Underhill home and drew up a business proposal, accenting it with watercolors to make it pop. The document, which he sent her at 4 a.m. the next day, asked United Therapeutics to put up $1.5 million in initial funding while Clark would contribute an equivalent value toward a rather conceptual goal: "elicit critical thinking in electric aviation."

Later that morning, he recalled, Rothblatt texted him: "You're on."

Rothblatt's backing helped Beta bring other investors and advisers aboard, including Dean Kamen, the New Hampshire-based creator of the Segway; Stone Point Capital CEO and Vermont native Charles Davis; and Boston Scientific cofounder and Shelburne resident John Abele. Clark was able to recruit top Vermont talent, including Steve Arms, founder of Williston sensor maker MicroStrain, who joined Beta in its first year. Clark also tapped locals, such as Ben Colbourn, who said he was working in Burlington's Generator maker space when Clark called looking for anyone knowledgeable about drones. Colbourn now oversees Beta's 3D printers, making sophisticated shapes from specialty materials at a rapid pace.

- Oliver Parini

- Benjamin Colbourn making scaled models of the Alia aircraft with a 3D printer

Early on, Clark approached Burlington International Airport in search of space for his startup. Airport director of aviation Gene Richards agreed to lease an aging hangar used by maintenance staff in exchange for repairs and improvements. To run flight tests, Beta also leased space across Lake Champlain at Plattsburgh International Airport, site of a former U.S. Air Force base.

Within 10 months, Beta's small team had designed, built and hovered its first eVTOL prototype in virtual secrecy. Ava, a somewhat spindly craft that wielded eight tilting propellers, served as a demonstration project. Its successful hover testing reeled in a $48 million contract from Rothblatt's company.

Once Ava was aloft, Clark said, he sent his first investor and potential customer sketches of what would become Alia. More importantly, Clark said, he pitched Rothblatt on his approach to making an aircraft that would have real-world use.

"It is focusing really deep into the motors, batteries, inverters, and being relatively conventional on the stuff that doesn't deserve innovation quite yet," he said late last month. "The materials science, the interiors, the avionics, the flight controls — those things are not going to take us from guzzling fuel in a jet engine to a new form of aviation. But the electric propulsion is."

Lift and Cruise

- Oliver Parini

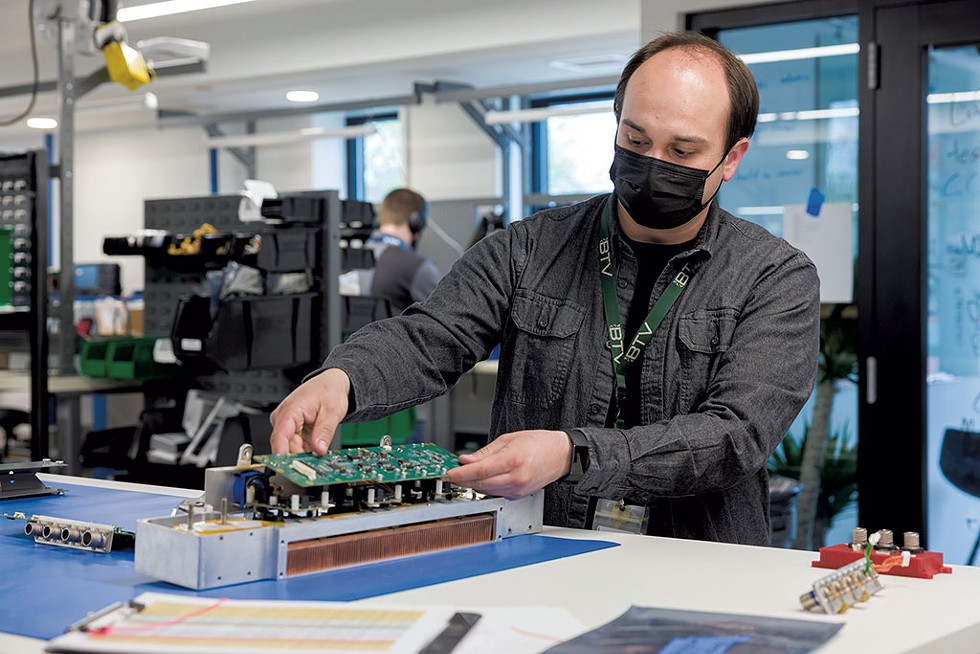

- Andrew Giroux working on air-cooled inverters

Commercial air travel accounts for roughly 3 percent of greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S., according to the Environmental Protection Agency. The relatively small figure is expected to grow, and unlike the auto industry, aviation hasn't had a clear path to renewable alternatives.

Electric flight is limited by both the amount of energy today's batteries can store relative to their weight — far less than jet fuel — and the immense power that aircraft need their propulsion systems to deliver to stay in the air.

Advancements in battery technology and the efficiency of electric motors in recent years have made electric-powered flight more plausible for small aircraft capable of carrying light loads for relatively short distances.

"The amount of power density you can get at any one time is better than it has been before, and the amount of power you need is less than it has been before," said Nicholas Roy, a professor of aeronautics and astronautics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. "So if the question is, 'Well, why now?,' it's the convergence of those two things. Do I think it has converged enough to really make this viable? That I don't know."

Beta has designed its electric propulsion system from the ground up. Alia uses powerful and efficient permanent magnet motors, the same family of motors used in today's electric cars. Clark said the company's 400-horsepower motors, which are air-cooled and don't require a gearbox, are capable of converting about 95 percent of electric energy into thrust.

"This is our core technology internally," Clark said as he showed off the motor's components.

Circuit boards for the inverters that control the motors are also designed in-house, while employees assemble massive battery packs from lithium-ion cells in a series of shipping containers next to the hangar.

Beta's decision to develop its own propulsion components distinguishes it from many of its competitors, who have partnered with legacy aviation firms such as Rolls-Royce and Safran, said Foley, the aviation analyst.

Alia's design takes advantage of Beta's in-house propulsion expertise. Whereas Ava, like many of the air taxis in development, used tiltable propellers to lift vertically and move forward, Alia has separate systems for lift and cruise that use motors specifically designed for each function. The design reflects Clark's emphasis on pragmatic thinking. "Real innovation happens as you say, 'How do I get that performance without increasing complexity?'" he said.

Alia is one of the largest, heaviest and most aerodynamic eVTOL designs to be built, said Mike Hirschberg, executive director of the Vertical Flight Society, a nonprofit industry educational group. Simplicity isn't typically a marker of strong performance in aviation, Hirschberg said, "but I think Beta has a nice balance." He considers the company one of the leading eVTOL developers, out of more than 200 who have put forward designs.

Last year, Beta got permission from the Federal Aviation Administration to begin initial test flights for Alia within a designated patch of airspace around the Plattsburgh airport.

Clark, who also serves as one of Beta's four test pilots, flew the prototype off airport property for the first time on New Year's Day this year. By March, the company had done enough successful testing that the FAA allowed Alia to fly beyond the initial flight area. Another pilot flew the aircraft across Lake Champlain back to BTV, where testing continues almost daily.

Most of the flight testing so far has been in fixed-wing mode, with the lift propellers detached and wheels installed under the fuselage. Alia had completed its 101st fixed-wing flight on the day that Clark took Seven Days for a tour of the hangar. Publicly available flight data from FlightAware tracked the aircraft flying more than 90 miles back and forth over Essex at a peak altitude of 5,900 feet and a top speed of 150 miles per hour.

Beta is one of the first companies working with the U.S. Air Force through an unusual public-private program intended to accelerate eVTOL development. Launched in 2020, Agility Prime makes Department of Defense funding and resources available to eVTOL developers and helps the Air Force evaluate whether the new forms of aircraft may have military applications. Knowing a homegrown company was working in the field, Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) helped funnel an extra $25 million into Agility Prime last year, his office said. The Air Force conducted ground tests on Alia last year to help establish its airworthiness, while Beta installed immersive flight simulators in Springfield, Ohio, and Washington, D.C., so officials can explore scenarios in which the aircraft might be useful.

With the military airworthiness authorization granted to Alia last month, the company can now conduct flight tests on the Air Force's dime as part of a contract that will pay Beta up to $44 million, Clark said. In a press release, Air Force Col. Nathan Diller said Beta's progress "shows the high level of maturity" of the company and emerging eVTOL technology.

Going to Market

- Courtesy Of Brian Jenkins/Beta Technologies

- The Alia flying over Burlington

Not everyone is sold. Richard Aboulafia, vice president of analysis at Virginia-based aerospace and defense analyst Teal Group, isn't necessarily skeptical about the progress in electric-aviation technology. He just thinks the notion that today's electric aircraft developers are revolutionizing travel is absurd.

Aboulafia is amused by what he considers an increasingly collective amnesia about the lessons of aviation's past. At the turn of the millennium, Eclipse Aviation, a dot-com-era darling, attracted hundreds of millions in investment to develop superlight, inexpensive personal jets that promised to democratize flight. The jets, it turned out, were not so cheap to make, and the company collapsed with $1 billion in debt.

To Aboulafia, today's ventures seem awfully familiar. Electric air taxi proponents, he argues, are overstating the market for a product that's still incredibly expensive to build. Helicopters are a niche industry, and it's hard to see electric equivalents — even though they are quieter and cheaper to maintain — expanding the market as dramatically as tech futurists and the people who give them money imagine.

"This is a recipe for carnage," he said. "Absolute carnage."

The last few months have seen a massive acceleration in funding for flying car startups, according to Robin Riedel, a more bullish analyst for McKinsey & Company. The consulting firm has tracked more than $4 billion in eVTOL investment so far in 2021, far more than last year or the $1 billion that was publicly disclosed in 2019.

Most of the recent capital has been provided through Wall Street's latest craze: special-purpose acquisition companies. SPACs, sometimes called blank-check companies, are publicly traded shells that exist solely to find a private company with which to merge. In the last couple of years they've become attractive as shortcuts to a traditional public offering. Three eVTOL makers have used the tool since February to raise as much as $1.6 billion each.

McKinsey projects that the global market for passenger eVTOL flights could be at least $300 billion annually. Others have estimated even larger revenue potential. "The investments that are going into this are reasonable," Riedel said, "if that is actually the market."

All that cash is crucial for startups to get a new kind of aircraft certified by the FAA and into production for commercial flight, which likely would cost more than $750 million, several analysts told Seven Days. Some eVTOL makers have said they can get it done within the next two to three years.

Clark asserts that Beta doesn't need as much money as the other companies because it has a clearer, quicker path to regulatory approval and a more straightforward business model. Unlike some other companies, Beta isn't trying to also establish a new passenger airline — it's just selling aircraft.

Asked during an interview in late April whether he was considering taking the company public to raise more money, Clark said that doing so would bring a "whole boatload of disadvantages," namely the requirement to communicate with public investors.

"We have the fortunate advantage of only having to convince our customers and the FAA that we have a safe, reliable aircraft that serves our mission," he said. "Not only do you get deposits and down payments from the customers, but you get credibility with alternative sources of funds."

Though Alia can be outfitted for pilotless urban travel, Beta is working primarily with UPS and United Therapeutics for regional piloted flights. Clark expects that the barriers to using the aircraft for cargo will be significantly lower. Its contract with UPS has an option to expand to 150 aircraft; Rothblatt said her company is seeking to deploy 60 aircraft in 2026.

eVTOL developers focusing on cargo uses have yet to attract investors to the same degree as those working on passenger applications, Riedel noted. Part of the reason is that planes are currently a small part of logistics and shipping businesses; the time they save usually isn't worth the cost.

"The cargo case really requires much more of a shift that is unknown," he said.

United Therapeutics is looking for planes that can fulfill organ delivery missions, but Rothblatt said the company's primary interest in eVTOL designs stems from its commitment to sustainability.

"It's no sense for us to be saving people's lives with organ transplants if we're trashing the whole world environment," she said.

Of her several bets on eVTOL, Rothblatt said Beta is poised to offer the longest flight range with a feasible route to certification.

"Kyle has designed a path for Beta which is challenging to get the FAA certification but definitely doable," she said. "And when he gets it, his aircraft will have the best performance characteristics, in my opinion, of any of the others."

Building Out

- Oliver Parini

- Kyle Clark (left) operating the flight simulator as reporter Derek Brouwer watches

Rothblatt's backing, Clark said, has allowed him to design the company according to his own vision, with a culture to reflect it.

Some aspects of Beta's organizational ethos can seem like tech startup gimmicks. Beta's many job postings seek engineers and technicians but also "gurus" and "ninjas." Yet once they join the company, employees refer to their job titles almost universally as "teammate." Clark insists there's merit to the idea. For example, taking time off doesn't hinge on supervisor approval but on teammates' agreement that the absence of a fellow worker won't leave them in the lurch.

The result is a cadre of entrepreneurial employees who, Clark said, "just care a whole hell of a lot about what they're doing, as opposed to a bunch of people that are trying to follow instructions or conform to something or climb the corporate ladder."

Since the beginning, Beta has encouraged all of its "teammates" to attain a pilot's license on company time under the tutelage of its several certified instructors. More than 30 have licenses, and 100 more are in training. The program has helped instill broader affection for and understanding of aviation, which leads, Clark believes, to smarter design.

Katie Clark oversees marketing, though she recently refashioned the marketing meetings as "band practice" to avoid boxing in their thinking. She hired a local chef to make lunch each day for the growing staff, who on a recent Wednesday stood in the rain for lunch at the company food truck. Katie and Kyle's four children, whom they homeschool, spend a lot of time at the office, too. Their 18-year-old daughter, Willa, has been working at Beta since she was 16. She said she started flying planes before she learned to drive.

As flight testing continues, the company is also gearing up to attain FAA certification and to manufacture Alia. Last fall Beta hired Matt Cherouny, a 35-year-old manufacturing engineer, to assess how to bring Alia into production. Cherouny grew up in South Burlington, attended the University of Vermont and worked for Green Mountain Coffee Roasters before going to work for Tesla in California several years ago. He's one of many Beta engineers who earned their degrees in Vermont.

"Visiting Beta made me realize I can move back to Vermont and I don't have to sacrifice my career and my personal beliefs" about sustainability, Cherouny said. He piloted his first solo flight last month, which was celebrated according to aviation tradition: by cutting off a piece of the shirt he was wearing.

Beta has not yet decided where to set up manufacturing operations, though it may well be at BTV. Vermont Business Magazine recently quoted a local contractor who said the company was eyeing a manufacturing facility there. Airport director Richards said Beta has an option to expand onto an open, nearly 40-acre parcel at the south end of the property. He confirmed "informal negotiations" with Beta about using it.

Clark's goal, he said, is to continue growing the business in Vermont, the home state of both his family and more than half of Beta's employees. He sees advantages to locating manufacturing operations near the engineering, so long as it also makes business sense. "Obviously, that requires everything from local community support to political support to financial reasons to make all that happen," he said.

Public officials are eager to help. Beta was approved over the winter for a Vermont Employment Growth Incentive payment of up to $2.8 million, according to state records. Burlington Mayor Miro Weinberger said in an interview that Beta is on track to have a "very significant economic impact" in the region doing work that dovetails with the city's climate priorities. "We will work hard to make the opportunity right when Beta is ready to make that decision," he said.

After Leahy visited Beta last week, a spokesperson said he will urge Congress to consider boosting the country's electric aircraft industry through President Joe Biden's proposed infrastructure bill.

"Beta has a very bright future," Leahy said in a statement, "and I want that future to be based right here in Vermont."

In the meantime, Beta is laying the literal groundwork to support its vision of electric flight. Like electric cars, an electric air network requires places to charge.

The company has devised an all-in-one landing and recharging system that can be installed at airports, warehouses and other locations. The units can charge any kind of electric vehicle and use battery banks to limit how much energy is pulled from the grid at any given time. Alia can be recharged in less than an hour, Beta says.

The company has already built out a network of recharging stations from Burlington to Springfield, Ohio, through small airports in western New York State that will enable Alia to make a longer trek. Clark plans to expand the network up and down the East and West coasts and eventually establish landing and recharging infrastructure nationwide.

A Beta-funded project to electrify Rutland's airport was under way last month, state aviation manager Dan Delabruere said. Some regional governments are already considering pursuing federal funds to add infrastructure to support electric aircraft.

The recharging stations, constructed in Williston, feature a landing deck perched above four containers that provide resting quarters, battery supply and a repair shop. The interior spaces are created from recycled shipping containers — a characteristically resourceful touch.

The station at BTV is visible along Airport Drive to motorists heading to the airport terminal. It looks cool, if a little provisional. Most people probably didn't imagine flying cars would be parked atop salvaged steel boxes. But Beta's clunky pads could be where that future finally gets off the ground.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.