- Courtesy of Ana Cuba

- Nico Muhly

Nico Muhly is not big on expectations. The lazy explanation for this would be because he so frequently defies them. Muhly, 35, is a globally lauded composer whose works traverse, blend and sometimes transcend the boundaries of contemporary classical, minimalist, experimental and pop music. He's scored films; counts Philip Glass as a friend, collaborator and mentor; and has worked with likes of Björk, Grizzly Bear, Joanna Newsome and Sufjan Stevens, to name a few. He is the youngest composer to have had an opera — 2011's acclaimed Two Boys — commissioned by the Metropolitan Opera. He has a deep and abiding love for sacred choral music.

Muhly's canon is diverse and unpredictable. But the real reason this former Vermonter balks at expectations is simpler: He has little use for them.

"A question a lot of people ask in advance of concerts is, 'What can we expect?'" Muhly says in a recent phone interview from his New York City studio — shortly after a reporter, um, asked him what to expect from his upcoming concert in White River Junction.

"I sometimes bristle at that one, because it's like, 'What the fuck are you expecting?' I'm not going to pull an elephant out of something," he continues. But then Muhly offers some advice: "You should expect to go to the concert, have a glass of white wine, have a great time and get the fuck out. When I go to a concert, that's what I expect."

On Friday, August 25, Muhly and his longtime friend and collaborator violist Nadia Sirota present "Drones & Ornaments; Strings & Hammers" at the Barrette Center for the Arts. The concert is the centerpiece of a larger celebration for the nearby Main Street Museum's 25th anniversary, which includes performances by Burlington's anarchist street band the Brass Balagan, Boston-based Tropicália-folk duo Só Sol and Upper Valley songwriter H. Seano Whitecloud — the latter as part of a bonfire party.

What is a man the Los Angeles Times has called "one of the leading classical composers of his generation" doing at a funky celebration for an even funkier museum in a small Vermont town?

For one thing, the MSM is something like the embodiment of Muhly's own creative worldview.

The curiosity-style museum, whose quirky catalog includes such items as "dehydrated" cats, Richard Nixon masks and mysterious things preserved in bottles, "is the perfect cultural gem for that city," he says. "It's a combination of style, DIY, humor, immersive art, specific art, obsession, collection, curation. It's all the things I try to do in my own music, just physicalized."

Muhly was born in Randolph and split his childhood years between Providence, R.I., and the Green Mountains. His parents are artists. His father, Frank Muhly, is a documentary filmmaker. His mother, Bunny Harvey, is a painter whose exhibition "Lost & Found" is on display at the MSM through September.

Comparing their art to that of the Main Street Museum, Muhly says, "My mother and my father have a very similar, perverse curatorial sense. The house is filled with little collections of, like, eggbeaters and this and that. I look around my house, and I realize I do the same thing: I have a piece of bad taxidermy; some weird, slightly pornographic Japanese finger cot; a stuffed bird; five Bread and Puppet posters."

Muhly's artistic output certainly reflects that eclectic curiosity.

"One wants one's music to feel like a joyful curation, a whimsical archive," he says.

His work is also, naturally, a reflection of himself. In conversation, Muhly speaks at a rapid pace; he's excitable, bordering on frantic. He's also deeply thoughtful, funny and sensitive. And he's insightful on a range of topics, from sacred music to artistic process to 1980s fantasy films.

"He's ebullient," says folk musician Sam Amidon, also a Vermont native and a longtime friend and frequent collaborator of Muhly's. "He's funny and overwhelming and intriguing. But he's a community-oriented person, as well as being a force of nature."

Amidon cites Muhly's need for friendship and community as key to understanding his artistic eclecticism.

"It's a combination of his extreme brilliance, linguistically and musically, and his desire for connection with other people," says Amidon. "It's not like he's some mad genius isolated in a room somewhere. He's so intense and so intelligent and this classic polymath. But, at the same time, he has this generosity, and he's committed to the social element of life being reflected in his art."

There might not be a better example of that sentiment than Planetarium, the recently released album Muhly composed and recorded with his friends: indie songwriter Stevens, Bryce Dessner of indie rockers the National and drummer James McAlister. It's a sweeping work, sonically and thematically, whose mysteries and grandeur reflect not just the cosmos but the Greek and Roman mythology that informed the project. Muhly's contributions to the record present almost as an anthology of his myriad musical pursuits: baroque-esque strings, droning, minimalist synths and seven bombastic trombones.

"I like the old-world tonality of his music," says Anne Decker, founder of local contemporary chamber ensemble TURNmusic. That group performed Muhly's "Drones, Variations, Ornaments" at its first concert in 2014. "And I like his minimalist vibe, hanging out in one place but having a groove to hang on to," she adds. "He has music that will really stretch your ears but is accessible."

Vermont audiences will soon discover Muhly's ear- and mind-opening charms for themselves. Ahead of Muhly's performance in White River Junction, Seven Days caught up with the composer by phone to ask him about, among other things, his childhood in Vermont, the making of Planetarium and his possible obsession with trombones.

- Courtesy of Ana Cuba

- Nico Muhly

SEVEN DAYS: Your parents are both artists. How did they figure into your artistic development?

NICO MUHLY: I was a relatively late bloomer as a musician. I didn't start until I was 9 or 10. Making art was an important thing in our house. My mother does it every day. It's part of her practice. In Vermont, particularly, it's this endless relationship — making art in the garden, in the studio, in the house. It's making the spaces work together. And that's where I learned how to do that. It's hard to describe, because one's musical DNA isn't ever as easy as it seems.

SD: Do you think being a late bloomer was in some ways advantageous?

NM: I do, actually. I have a lot of friends who are extraordinary musicians and were handed a violin at, like, 3. But for me, because I was exposed to a lot of different worlds and different ideas, really the world of ideas — basically not being hyper-focused as a child, growing up in a house with a lot of different kinds of people coming in and out — what that translated to later, as a direct result, was realizing that it's not just about being a musician. Reading things and thinking about stuff and studying other languages and learning about things that you're randomly and obliquely interested in is much more productive to making music.

SD: Do you thrive working on a deadline?

NM: I do. I was talking to some composer friends the other day, and we all have different relationships to deadlines. I have friends who need to start the paper before it's due, and they'll turn out amazing, detailed work. The adrenaline soothes them.

I'm the opposite. I tend to get ahead of things and then finish projects under pressure. It's sort of like filling up your freezer with stock: You know that there is at least some option stored.

SD: Working under constant deadline pressure, one of my biggest fears is writer's block. Do you ever have the musical equivalent?

NM: I find the pressure forces me to have an idea. Knock on wood, I've never experienced what I'd call traditional writer's block, yet. I've had moments where I've been frustrated by limited time, which is why I start things so early and have sketches and permutations of the work for myself. It's like a little gift you give yourself, in case you find yourself up against the wall. Which, of course, you will.

SD: As a composer, what's it like hearing other people bring your ideas to life?

NM: I imagine it's like a playwright and hearing other people do your thing. It's exhilarating. The hardest drug I know of is the first two seconds when an orchestra plays your work. It's a crazy feeling. And it's a feeling I always chase. Massed sound is an amazing experience; it's magic.

SD: Are you ever disappointed? Like, "Well, that's not what I was going for."

NM: I think because I'm also a performer, I never have that feeling of, "Oh, no, you're messing it up!" And it's because there are so many situations in which I do have total control. Also, I write for other people that stretch them in ways that I, as a performer, couldn't be stretched. I haven't taken a piano lesson since 1999. I practice, but only when I have to do something. So, one of the ways I can learn is by sitting back and watching other people maneuver through the challenges of it.

SD: You've spoken about the idea of "vanishing," that being invisible as a performer is one way you know you've done your job, particularly when performing sacred music. What do you mean by that?

NM: When you think about the role of sacred music — and I'm oversimplifying this — it can and should be as emotionally present in the act of worship as, for instance, a building. Yes, you can go out in a field and worship alone. But, in the Anglican tradition that I come from, it's about having this music in a beautiful and consecrated space, with a certain amount of ritual to it. And, taken together, that should — should — equal an experience that effaces all of the individual elements and adds up to this larger-than-life experience.

Three days ago, I was in Winchester, outside of London, and I popped into Evensong. There were, like, 25 people in Winchester Cathedral, which is this enormous, fabulous thing. And the music is enormous and fabulous. And you don't really think about how it works; you think about the experience — as opposed to a Beethoven concert. Beethoven is great. You care about Beethoven, his intent, the liner notes, the musicians. Whereas, in the Lord's house, none of that matters.

SD: Planetarium was originally conceived as a live work. How much did it change when you put it on record?

NM: Enormously. It was originally conceived as this outrageous concert piece with seven trombones and a string quartet and this crazy visual element. And then, when it came time to record it, we took it deeply apart. And there was a huge lag, like six years from when we made it to when it came out. And in that time we all grew enormously as artists. So, it changed a lot, and I think that's a good thing.

Many of the sounds are completely new. Chords got changed, and there are more electronic and acoustic instruments. I don't want to say it's a remix, but it's a reassembly of how we built it.

SD: Can you identify any specific ways in which it changed?

NM: A good example would be "Saturn." It's like a club banger and much harder. Though we went out and played it recently and sort of made it a hybrid of what we've done live and what's on the album. And that was fun, too.

That's the fun of working in that way, for me. Because, in notated music, the text is the text. You don't go around making new versions of everything for a different batch of shows — the viola concerto is the viola concerto. So, it's a luxury for me to work that way.

SD: Do you have a trombone fetish? Why seven?

NM: [Laughs.] No. There's the practical reason and the funny reason. We made this piece as part of a commission. I had to be a composer-in-residence in this town in the Netherlands called Eindhoven. I was thinking about what would be kind of fun to do while playing with Dutch government money. And large, massed sound is really fun to me. So, large homophonic ensembles are something I don't really get to play around with that often.

No. 2, I thought for the boys it would be a step away from the way they normally orchestrate their music. So, for Bryce, who does many of the arrangements for the National, it's like three or four horns and strings — it's intricate. And for Sufjan, it's a lot of high end, a lot of piccolo, a lot of bright, brilliant things. I thought it would be fun to take all the muscularity of the music and insist on it with the trombones. And it worked.

Seven trombones is such a fabulous sound that you don't hear often. And it's otherworldly to me. It feels like something that you recognize, but don't quite.

SD: I was surprised to learn that one of the inspirations for Planetarium was 1982 fantasy film The Dark Crystal.

NM: If you listen to any of those movies from that time — Labyrinth, for example — any kind of otherworldly music that happened [in the 1980s], sci-fi or fantasy, it really has that synth base.

If you posit that Howard Shore's scores for The Lord of the Rings or The Hobbit are the best examples of [otherworldly film music] we have — they're epic and symphonic and recognize the sweep of things. With the exception of Star Wars, the way we create that is through synthesized sounds. So, the Wagnerian realism in something like Lord of the Rings or, indeed, Star Wars is one approach to a sweeping narrative. Another is decidedly synthesized.

Also, have you watched Labyrinth or The Dark Crystal recently?

SD: Actually, yes.

NM: That shit is crazy! I don't think you could get away with making that for kids these days. That scene [in The Dark Crystal] where they strip that Skeksis down to his bare skeleton, I still think about that. And, funnily enough, since we were talking about church, if you go to a high church and they have all those robes and shit, sometimes your mind goes there, doesn't it? Like there's all this shit crusted on everyone in this sumptuary way. But it was very human, I thought, the denuding of the Skeskis. I wanted to sympathize.

SD: Sufjan has talked about how the lyrics were intentionally left open to interpretation — I think he's used the term "word salad." As someone who quite literally interpreted what he was writing, how much did you use the lyrics as a reference point?

NM: It's funny you say that. The way that we built [Planetarium] was so palimpsestic that sometimes the music came first, and the lyrics came way afterwards. But, for me, some of the more poignant lyrical moments helped me to play things better. For example, in "Mercury," at the end of the beginning section before it goes wordless, there's a poetry that I found very [moving]: "Where do you run to, carrier friend?"

It's such a beautiful line, with so many possibilities. It's very him but also very abstract. And it's very Greek and very Roman. And you can picture Mercury and the helmet and the wings. When we're playing it live, I always wait for it and always get quite moved.

SD: When I interpret what Sufjan is writing, or try to, I see the album as exploring the intersection of faith and science. It's about Roman and Greek mythology, but also the cosmos. So it's interesting to me that this album comes at a time when faith and science increasingly feel divorced.

NM: Half of Tumblr is dedicated to figuring out what Sufjan is talking about. I think I'm the wrong person to ask. I'm too close to the eye of the storm.

But I do think that a great piece of writing is timely no matter what else is going on. It's easy to retrofit art into a political moment, which I don't feel is a particularly useful way to think about it. You're more than welcome to. It's just not part of my process.

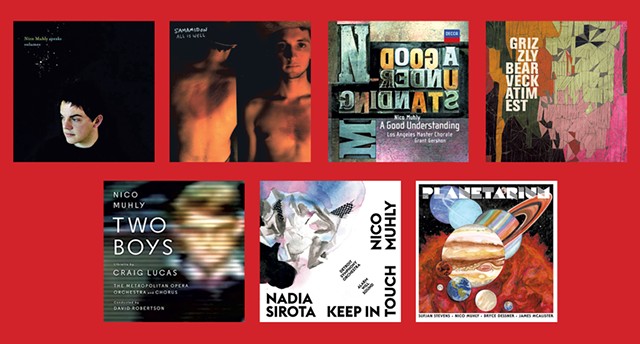

Nico Muhly: A Selected Discography

Nico Muhly's recorded catalog is as voluminous as it is fascinating. As such, it's hard to know where a curious listener should begin.To get you started, here are seven choice recordings highlighting both his solo works and collaborative projects.

Speaks Volumes, Nico Muhly (2006)

Muhly's debut solo album was widely hailed as foreshadowing a sea change in modern classical and chamber music. It's an elegant and melancholy collection of suites for small ensembles that treats electronic and acoustic instruments with equal affection.

All Is Well, Sam Amidon (2008)

Amidon's second album, a collection of deconstructed Appalachian folk music, is remarkable in its own right. But Muhly's contributions give it an extra layer of gothic sonic intrigue.

A Good Understanding, Nico Muhly, the Los Angeles Master Chorale (2010)

This is a stirring example of what Muhly can do with a mass of voices. The album sets familiar Christian texts — and one secular piece by Walt Whitman — to compositions that merge the aesthetics and tonality of sacred choral music with modern techniques that nod to minimalist masters such as Steve Reich.

Veckatimest, Grizzly Bear (2009)

Grizzly Bear's 2009 album was the indie-rock band's breakout. The swirling warmth of Muhly's arrangements on numerous tracks certainly doesn't hurt.

Two Boys, Nico Muhly (2014)

Performed by the Metropolitan Opera and released on Nonesuch Records, this album of Muhly's acclaimed, and mildly controversial, opera is a dramatic exercise in moody minimalism.

Keep in Touch, Nico Muhly & Nadia Sirota (2016)

Muhly and Sirota have been friends and collaborators since they were teenagers at the Juilliard School. Keep in Touch, recorded with the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, is a tender, dizzying meditation on friendship. It's affecting both for its opaque themes and for the brilliant construction — and performance — of its sensational viola concerto.

Planetarium, Sufjan Stevens, Nico Muhly, Bryce Dessner and James McAlister (2017)

One word: otherworldly. A few more: a perfect gateway to Muhly for more pop-inclined ears.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.