- Oliver Parini

- Duck with toasted polenta, a blueberry glaze and sunchoke chips at Sweetwaters

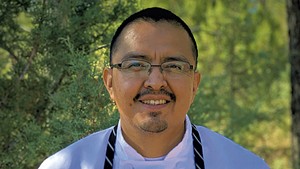

Seated in the dining room of Sweetwaters on a recent afternoon, the Burlington restaurant's executive chef, Jessee Lawyer, pulled two tribal identification cards out of his wallet.

One had a photo of Lawyer's serious, bearded face in the top left corner. Text printed to the right said: "The card certifies citizenship in the St. Francis/Sokoki Band of the Abenaki Nation of the Missisquoi."

The second card, yellowed with age, had a photo of Lawyer's late father, John, his broad smile framed by long, dark hair.

Lawyer had just cooked a three-course demonstration meal featuring many traditional Abenaki ingredients: seared duck breast with toasted cornmeal polenta, blueberry glaze and sunchoke chips; maple-brûléed squash with smoked-squash broth, wild rice and roasted squash seeds; and a sunflower seed- and cornmeal-crusted squash pie with blueberry sauce.

According to the chef, the inspiration for the duck was an Abenaki legend in which the hero distracts an evil wizard with dried meat boiled with blueberries and maple sugar.

The duck dish became a weekend special with a mention of its indigenous connection. This meal is not what one might expect at Sweetwaters, a Church Street standby known more for burgers, nachos and salads. But since the beginning of summer, Lawyer has been offering Abenaki specials about once a week, combining traditional ingredients with indigenous and European cooking techniques.

"If you just do what was done hundreds of years ago, it's not a living, breathing culture. There needs to be growth," explained Lawyer, 32. "I just want people to recognize that this is an actual type of food. We are reclaiming and decolonizing our foodways, not only for ourselves but for the general public."

Decolonizing involves the rediscovery and honoring of indigenous traditions that have been devalued, stifled or prohibited due to colonial oppression and its aftermath.

- Oliver Parini

- Squash three ways at Sweetwaters

During the eugenics movement of the first half of the 20th century, both in Vermont and nationwide, those with Native American blood were among the groups obliged to hide their heritage to avoid persecution, institutionalization and even forced sterilization.

Unlike many among the older generations, Lawyer's father, John, openly claimed his Abenaki identity. "In my family," Lawyer recalled, "it wasn't hidden as much. My dad told me my grandmother hid it but my grandfather didn't."

Lawyer's father grew up in Alburgh and Burlington in the 1940s and '50s. He wasn't always proud of his roots, something he later told his son he regretted. "It really wasn't cool to be Native back then," Lawyer noted with understatement.

According to the website of the Vermont Commission on Native American Affairs, at least 1,700 Vermonters claim to be direct descendants of indigenous Native communities.

Starting in the 1990s, John became active in the effort to gain recognition for Native Americans in Vermont. The legislature eventually established a state process for recognizing Native American Indian tribes in 2010.

Subsequent official recognition of four tribes within the Abenaki Nation — including the St. Francis/Sokoki Band, to which the Lawyers belong — prompted renewed efforts to preserve and share their history and traditions.

During his own childhood, Lawyer said, food traditions were less a focus than the Abenaki art skills of his father, which earned him a living and local acclaim.

Shortly before John passed away in 2013, Lawyer became interested in his heritage, including the foodways.

"I was in New York State working in a pizza shop. I hadn't really begun to think of indigenous foods," he recalled. "We went up to a tribal council meeting together. Dad said, 'Learn as much as you can from Fred Wiseman.'"

Wiseman is an ethnobotanist and retired professor who lives in Swanton. He has Abenaki lineage on his paternal mother's side and had worked with John over the years advocating for tribal recognition.

In 2012, Wiseman started a project called the Seeds of Renewal to find and preserve seeds cultivated by the Abenaki and other regional Native communities. He has gathered about 50 different seeds through networking. They range beyond the "three sisters" of corn, squash and beans — a popular culture understanding of Native American agriculture — to include sunflowers, Jerusalem artichokes and ground cherries. Tobacco was also grown for ceremonial purposes.

Varieties have been named for the towns in which they were saved, such as the Morrisville sunflower and the Hardwick ground cherry, or sometimes after a specific tribe, such as Koas corn. Wiseman is working with the Intervale Center, the Ethan Allen Homestead Museum and Sterling College to catalog and protect the seeds.

But seed saving is just the start, he emphasized. Wiseman's goal is to build a complete understanding of traditional agricultural practices. His research indicates that the Abenaki practiced complex soil-management systems; seasonal ceremonies and cooking techniques were also integral.

"In Native society," Wiseman explained, "dances like the sun dance, rain dance and green corn dance are a very important part of the food system. We believe you cannot nurture seeds with human energy alone."

Wiseman helped start a recently established nonprofit called Alnôbaiwi, an intertribal organization of people with Abenaki and other Native American heritage. The word means "in the Abenaki way," explained the group's cochair Kerry Wood during a mid-August tour of a garden in Burlington's Intervale that was planted with seeds from Wiseman's project.

"I didn't know I was Abenaki until I was well into high school," said Wood, 56. "My great aunt says her mother would not teach her the Abenaki language. Families would say, 'Don't talk about it. It's not safe.'"

The group is dedicated to building community around revitalizing and celebrating Abenaki culture, she explained: "If we don't [do that], then the assimilation is complete."

Alnôbaiwi partnered with Ethan Allen Homestead to host a traditional green corn celebration on September 14. It was exceptionally windy as Wiseman guided more than 75 people through traditional dances and other activities to honor the harvest of fresh corn on the cob. The corn was later roasted and eaten.

An impressive wigwam structure built from hand-hewn cedar lodge poles reached to the sky; its canvas cover had not been put on due to the weather. The outdoor kitchen was centered around a stone-bordered fire, flanked by colorful pumpkins, including the Abenaki varieties, Penobscot and Worcester.

- Oliver Parini

- Sweetwaters chef Jessee Lawyer

Maine yellow eye beans, another traditional seed, had been cooking for hours in a bean hole dug three feet deep. They were seasoned with salt pork and maple syrup — but would have been made with bear grease and maple sugar before European contact, Wiseman explained.

Many tribal members from around Vermont came to share their expertise and stories. Shirly Hook, Doug Bent and Colin Wood were seated by another in-ground oven in which a turkey was cooking near a fire over which an elk and vegetable stew was simmering.

Hook and Wood are cochiefs of the Koasek of the Koas Abenaki Nation. Bent's great-great-grandmother was Native American, though he's not sure which tribe.

Hook, who is Bent's partner, grew up in Chelsea. "My brother found a letter from 1932," she recounted. "It was from two cousins, children, who had been taken to the Brandon Training School where they did a lot of the sterilization. They tried to telegram back to the family, but it came too late."

Hook and Bent cultivate a large garden at their Braintree home, including many varieties from the Seeds of Renewal project. In turn, they contributed the Koas corn to the effort. "We have 200 ears hanging to dry from the rafters back at the house," Bent said.

Lawyer is a member of the Alnôbaiwi group, too, but he was working the day of the green corn ceremony. He knows Hook and Bent and hopes they will save him some Koas corn cobs to use for smoking ingredients.

The chef continues to work on honoring the foodways of his ancestors by researching, reading and experimenting. In May at Dartmouth College, he cooked alongside a leader in Native American cuisine: Sean Sherman, a James Beard Award-winning chef from Minneapolis. In addition to continued specials at Sweetwaters, Lawyer has also made guest appearances at other local restaurants; he'll be at the Great Northern in Burlington in early December.

Lawyer appreciates the opportunity to apply his professional skills in such a personal way. Since Samuel de Champlain arrived in Québec in 1608, he said, "Our numbers have been decimated, the language is almost gone, the food crops almost lost. But we're still here; we've stood the test of time. Without practicing our culture, we become extinct."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.