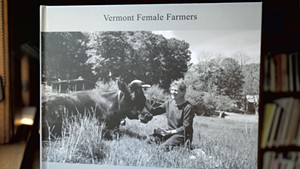

- JuanCarlos Gonzalez

- SUSU CommUNITY Farm cofounders Amber Arnold (bottom) and naomi doe moody (top) with field and farm director Kyana Ferro

The small, temporary sign stuck into the grass in front of the former Maple Row Farm in Newfane heralds something simultaneously new and deeply historic.

A dark-brown hand reminiscent of the Black Power fist holds aloft sweet potatoes with their greens. The text informs visitors they have arrived at SUSU CommUNITY Farm, which is "sowing seeds of liberation in Vermont."

In mid-April, SUSU cofounders Amber Arnold and naomi doe moody signed a lease for the 37-acre farm, which the Vermont Land Trust purchased at the end of March for about $500,000.

SUSU's seven-member team is in the final stages of establishing the organization as an independent nonprofit and plans to buy the farm from the land trust once that is finalized. It is currently raising funds for the purchase and to build farm infrastructure.

Walking the path back from the West River to the farm's lower field on a recent June afternoon, Arnold said she was not surprised by how far she and doe moody have come since they cofounded their original SUSU Healing Collective in 2019.

"This is what our ancestors told us was going to happen — and it's happening," Arnold said.

Ancestral wisdom is core to everything Arnold and doe moody do. It is the key, they explained, to healing from the deep racial trauma that goes back to colonialism and the transatlantic slave trade. They build strength from "connecting back with our ancestors and lineages and practices that we've been disconnected from," Arnold said.

The name SUSU pays homage to sou-sou, the West African word for a money-lending circle. "Members of the community come together. They pool money, and each person in turn gets to receive the pool of money," doe moody explained.

Such informal savings and loan programs have long served to raise money for those with limited access to bank loans. While SUSU has not used this practice, doe moody said it embodies the same spirit of mutual aid and reciprocity.

"It's a community effort to bring the farm to life. People can come together to create this beautiful thing," doe moody said.

"We're taking care of each other," Arnold added.

- Courtesy Of Susu Community Farm

- Jarmal Arnold

Arnold, 30, and doe moody, 44, met in 2018 at the inaugural BIPOC Caucus statewide retreat. The following year, the pair cofounded the SUSU Healing Collective in Brattleboro. It offered yoga, sound and energy healing, herbal consultations, and a botanica integrating traditional African and Indigenous practices. Those activities now fall under the umbrella of what they call "an Afro-Indigenous-stewarded farm and land-based healing center."

COVID-19 closed the healing collective's physical space. But the pandemic and the nationwide wave of racial justice protests in 2020 further emphasized the need for healing and reparations.

Arnold and doe moody responded to the pandemic-related spike in food insecurity by launching a crowdfunding campaign to buy community-supported agriculture farm shares for Windham County BIPOC residents.

"You were hearing people say things like, 'Oh, we're so lucky. We live in Vermont; we have so much access to all of this [local food]'," doe moody said. "It was just like, But who does? Because I could really use a CSA right now, and there's no way I could afford one."

While acknowledging the severity of police violence, Arnold explained that barriers to fresh, healthy food are another insidious form of violence against people of color.

"There's a big correlation between the foods that we put in our bodies and overall health," Arnold noted. "We believe that food is a birthright and not a commodity. Everyone should have access to nourishing, life-giving food."

- Courtesy Of Susu Community Farm

- Jarmal Arnold with daughter, Leylani, in 2021

Within four days, the SUSU Healing Collective raised more than $20,000 to purchase 25 farm shares from Circle Mountain Farm in Guilford and a farm in Massachusetts. These "boxes of resilience" were free to households that included a self-identified person of color. Now in its third year, the program has grown to 60 shares.

Participant Dora Urujeni is originally from Rwanda and moved to Brattleboro in 2017 to earn a master's degree from the School for International Training. The case manager for the Community Asylum Seekers Project has a 6-year-old son; she met Arnold at their children's preschool.

When Arnold first told her about the resilience boxes, Urujeni said she was very grateful. "It was such a hard time. People were struggling," the single parent said in a phone interview. She especially valued how Arnold emphasized that "this box is not a gift," Urujeni recalled. "It's your right."

In addition, Urujeni said, "Getting food from a sister, somebody [with whom] you share identity and history, it's an added value. It's like liberation."

In its second year, SUSU continued to source food from other farms while growing 1,400 pounds of produce, including okra, hot peppers and collards, at Brattleboro's Retreat Farm.

The cofounders also started looking for their own land. Buoyed by the strong support and response to what they were doing, Arnold and doe moody saw an opportunity to act upon the advice of their elders.

"What does Fannie Lou Hamer say?" Arnold asked rhetorically, referencing the legendary civil rights activist. "If you give a man food, he'll eat it. But if you give him land, he'll grow his own food."

All told, SUSU's original GoFundMe effort raised close to $200,000. "The money just kept coming," doe moody said. "People were invested in trying to change something."

- Juancarlos Gonzalez

- From left: Amber Arnold, naomi doe moody and Kyana Ferro

Nick Richardson, Vermont Land Trust's president and CEO, recognized that SUSU was "a really powerful organization" building "connections and community and relationships in the southern part of the state around issues of BIPOC land assets, ownership and management."

The land trust has partnered closely with the SUSU team to understand and support its goals, eventually helping to facilitate the Newfane farm purchase.

Doe moody pointed out that for many Black Americans and other people of color, however, working the land comes with heavy baggage.

Speaking as someone who "comes from sharecroppers and enslaved people, just the act of farming in itself is not healing for me," doe moody said. "It has to be a very intentional reclamation of ancestral practice in order to do that work."

Growing traditional African crops is critical. "They wove the seeds into their hair to bring here for us," doe moody said.

This year, the SUSU team had hoped to grow much of the 20-week farm share on the Newfane farm, but potable water issues on the property delayed the closing.

The team has collaborated with Circle Mountain Farm to grow produce, including Cherokee moon and star watermelons, Alabama blue collards, egusi melons, and West African spinach. Other items are purchased from or donated by local farms and food producers.

- Courtesy Of Susu Community Farm

- SUSU CommUNITY Farm volunteer Mikaela Simms in 2021

But the SUSU team and volunteers are making up for lost time. Over the last two months, they have planted a two-acre orchard with hundreds of trees and bushes, including apples, persimmons, pawpaws, pecans and elderberries. They've started building soil fertility and garden beds, and they've hosted weekly farm share pickups and events, such as a recent plant walk.

In the lower field, co-land steward Kegan Refalo was completing work on the first circular quarter-acre garden plot, layering rich compost over cardboard.

SUSU's agricultural approach has been carefully conceived to benefit the environment and draw on ancestral models. The farm is no-till and deploys methods such as sheet mulching that doe moody said reflect Indigenous practices.

The circle design represents a sacred medicine wheel, doe moody explained, used by the Dagara, an Indigenous people of West Africa. The wheel encompasses the cycle of life, including different elements and energies.

To the north, for example, is water, "which is about reconciliation and peacemaking," doe moody said. "In today's terms, you could say things like 'restorative justice.'"

The center is Earth, which represents mutual aid and reciprocity: "the energy of giving and receiving; it's the sou-sou," doe moody continued.

Other points on the wheel hold nature and the wisdom of ancestors. Together, doe moody said, they all combine into "the universal life force that connects us to everything," including the nonhuman world. The medicine wheel reminds humans that "We're a part of it, not apart from it."

SUSU also offers a range of workshops on topics including understanding white supremacist culture and healing from trauma. "These things are all interconnected," Arnold said. "There is no separation between spirituality, food, land, healing, living, having children."

- Juancarlos Gonzalez

- The first SUSU CommUNITY Farm garden plot, representing a Dagara medicine wheel

The cofounders each live with their families in the property's rambling blue farmhouse. A swing hangs from a majestic maple tree, and their kids bike up and down the driveway between the house, a cupola-topped red barn and several outbuildings, including a sugarhouse.

Future plans include building a farmstand, a hoop house, a botanica and an education center. This spring, a group of 30 New York City middle schoolers visited the farm. The students helped build garden beds, harvested red clover from the meadow and saw a bear swimming in the river.

A few CSA members trickled through to pick up their shares. Only about 15 of the 60 members opt to come to the farm; the rest receive home delivery, eliminating another barrier, Arnold and doe moody said.

A father and his young son arrived and chatted for a while with Jarmal Arnold, Amber Arnold's husband and SUSU's co-land steward. They took home eggs, chard, lettuce, bok choy, radishes, bread and strawberries, as well as herbal tinctures and natural sunscreen. The boy carefully carried a six-pack of zinnia starts back to the car.

Urujeni receives home delivery, but she recently volunteered for several hours to help build the gardens. "Land is very important," she said. "You feel like: This is where I belong. This is really what belongs to me."

Her son, she said, loves all of the food that comes in their share. "Being able to grow something from the land and then having that food on the table, it's something really wonderful to feel," Urujeni said.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.