- David Shaw

- Peter Dixon

Peter Dixon leans over the textbook he wrote, Farmstead Cheesemaking Collection, and peers at his calculations. "How thick are the mycelium?" he asks his student, a Jersey cow farmer. "You look at that chart and see how powerful each of these mold cultures are."

This may sound like white-coat science, but Dixon's analysis is taking place in his cheese house in Westminster West, not a laboratory. The cheese he's examining has been aging for a month and a half, and his work will result in several wheels of Brie.

Dixon, 57, may not be as recognizable as some of Vermont's culinary movers and shakers, but he should be: Over a 32-year career, he helped to create many of Vermont's most important cheeses, from Shelburne Farms cheddar to Vermont Creamery chèvre to Taylor Farm's Gouda.

"We are all so familiar with his cheeses," says Meghan Sheradin, executive director of the Vermont Fresh Network. She considers Dixon "the king of cheese."

Indeed, his résumé reads like a history of small-scale cheese production in Vermont. The son of a dairy farmer, Dixon began his cheesemaking career in 1983, the same year the American Cheese Society was born. He augmented his knowledge of home-style traditions with European expertise. In time, he became an internationally in-demand consultant and a teacher whose influence has helped put the artisan in the Vermont cheese movement.

Of course, Dixon drew upon a long history of local cheesemaking. Hard, English-style cheeses began showing up in New England 20 years after the pilgrims arrived at Plymouth Rock, according to Jeff Roberts, Montpelier-based author of The Atlas of American Artisan Cheese. Through the ensuing centuries, women crafted farmstead cheese from the milk their husbands provided. Not until the 1850s did cheesemaking outside the home gain a foothold.

- David Shaw

- Caciocavallos, hanging and sliced (below)

And then it wasn't long before cheese became a factory-made commodity. In his research, Roberts was able to identify only 39 small cheesemakers operating in the U.S. in 1950, for example. But in the 1980s, farmers began to return to the tradition, hoping to find customers willing to eschew the Kraft and Velveeta products that had taken over the American table.

One of those farmers was John Dixon, Peter Dixon's father, who was seeking a new income source to replace his raw-milk bottling business. In the 1970s, Vermont farms with special licenses had been able to sell raw milk, but the program ended in 1982 after a related illness made the agriculture department rethink the practice.

The senior Dixon looked to cheese production as a way to save the farm and perhaps support the family — while bringing his grown children back into the fold.

Peter Dixon's brother, Sam, had obvious credentials: He was already studying animal science at the University of Vermont. (Today, Sam is the dairy manager at Shelburne Farms.) Peter's calling was less obvious. "I was playing rock and roll in Portland, Maine, just bumming around," he recalls. "I realized I didn't want to be a professional musician. So I thought, I'll be a cheesemaker."

French Connections

If you remember the 1980s, you remember the Brie. Having a wheel of the oozing cheese on the counter at a party was a symbol of sophistication akin to eating sushi or satay. But that Brie, Dixon points out, bore little resemblance to the real French item. "All Americans knew was supermarket Brie," he says. "American consumers want a mild cheese, and the French knew that, so when they started creating a Brie for Americans, they designed it to be very mild and white."

- David Shaw

- Humble Herdsman

Not so the Brie the Dixons set out to create under their new brand, Guilford Cheese Company. After mastering a Neufchâtel-style fromage blanc, they set their sights on a piquant, French-style Brie made from pasteurized American milk. Peter Dixon headed to Ontario's University of Guelph, where he learned to make Camembert and 10 other types of cheese. His education contributed to two cheeses for Guilford: Mont-Brie and Mont-Bert, pasteurized approximations of the French originals.

Vermont-based writer Marialisa Calta chronicled the Dixons' results in a 1986 New York Times story called "An Experiment in Cheese-Making: Brie From Vermont." At a University of Vermont tasting, the third-generation owner of France's award-winning Fromagerie Renard-Gillard "sniffed" the Dixons' cheese and "squinted at the rind through a magnifying glass. Occasionally, he even tasted," Calta wrote.

At length, Jean-Francois Renard pronounced himself "not totally satisfied" with this upstart American Brie. But, he conceded through an interpreter, the Dixons were "willing to work very hard. The project will continue."

It was the beginning of a loose exchange program that allowed Peter Dixon to study traditional cheesemaking in France. Back in the U.S., he continued to learn French-style production from Marie-Claude Chaleix, a consultant who had partnered with Dixon's stepmother, Anne. "It was really with [Chaleix] that I got an educational window into French cheesemaking," he says.

Artisan Pioneers

Anne Dixon and Marie-Claude Chaleix were selling cheese in a very different culinary climate from today's. "There were no farmers markets, and hardly any restaurants were using Brie of any quality," Peter Dixon recalls.

In a 2013 interview with Seven Days, Paul Kindstedt, a UVM cheese scientist and author of Cheese and Culture: A History or Cheese and its Place in Western Civilization, remembered his first impressions of the artisan cheese movement. Back in the 1980s, Kindstedt focused his studies on large-scale mozzarella production and viewed artisan cheese as "a passing fad. It's hippies," he recalled thinking. Then, he said, "I watched the hippies grow up, basically."

- David Shaw

That countercultural coming of age didn't come soon enough to save Guilford Cheese Company, which closed in the late 1980s. "We had financial trouble," Dixon explains. "We were pioneering in this business at a weird time."

The failure didn't diminish his ardor for creating cheese. Dixon enrolled in the dairy-science program at UVM and became a cheesemaker at Shelburne Farms. There, he focused on the farm's enduringly popular cheddar, but, he says, "I didn't just stick with making cheddar." That's an understatement.

In the mid-1990s, Dixon turned his attention to Websterville's Vermont Creamery, then called Vermont Butter & Cheese Company, which was looking to grow beyond the chèvre that had made its name. He conceived a fontina for the company, then a white-rinded goat cheese called Chevrier. Neither cheese lasted, but the latter lives on in an evocative description from famed chef Judy Rodgers' The Zuni Café Cookbook: "It has a mellow, round flavor with notes of field mushroom."

In 1997, Dixon became a consultant, making regular stops in such places as Macedonia, Albania and Armenia. In more recent years, he has developed cheeses for Ambrosia Dairy in Shanghai.

- David Shaw

- West West Brie

But Dixon prefers to stick closer to his home in Westminster West. "I can do that [consulting] here because we have a burgeoning artisan cheese movement now," he says. "It's not like when I was with my family, and it was just a bunch of pioneers who don't know an awful lot. Now it's a lot more people who don't know an awful lot."

Self-deprecation aside, Dixon has made a career of spreading his own knowledge far and wide. Today, more than 150 varieties of cheese are made in Vermont — which means many cheesemakers seek help from Dixon as a consultant or teacher.

"He was one of those guys who was out there really helping so many cheesemakers come up with their recipes," says Sheradin of the Vermont Fresh Network. She attests to Dixon's hands-on educational approach: "He is in the vat, making the cheese and the recipes right on-site."

The results speak for themselves. Take the case of the Taylor Farm in Londonderry. At the turn of this century, sibling owners Jonathan and Mimi Wright had plans to make provolone or Swiss, but that changed when they enlisted Dixon's help. With his guidance, "We experimented, and we went to visit farms and see what they were doing," Mimi recalls. The Wrights found "plenty of cheddars," so they decided to carve out a different niche: "The Gouda worked right from the start," Mimi says. The farm still makes Vermont's only version of the Dutch cheese.

Without Dixon, Vermont would have a very different cheese landscape — no Taylor Farm Gouda, no Cobb Hill Cheese Ascutney Mountain, no Woodcock Farm goat or cow cheeses. But his greatest success of the new millennium — before he started his Parish Hill Creamery with his wife, Rachel Fritz Schaal, in 2013 — was the creation of Consider Bardwell Farm's cheeses. Dixon spent six years with the West Pawlet operation, first as a consultant, then as head cheesemaker. In that time, his big wheels, named for nearby towns such as Dorset and Manchester, racked up equally sizable awards.

Cheese Ed

Dixon's greatest legacy may be as an educator. One of his successful pupils is Leslie Goff, Consider Bardwell's current cheesemaker; she was just 17 when she made her first cheese alongside Dixon while working with the farm's goats. "I kind of fell into the cheesemaking one winter because Peter needed more help washing the cheese," she says. "He showed me the ropes." A decade later, Goff is crafting her own cheeses for the farm.

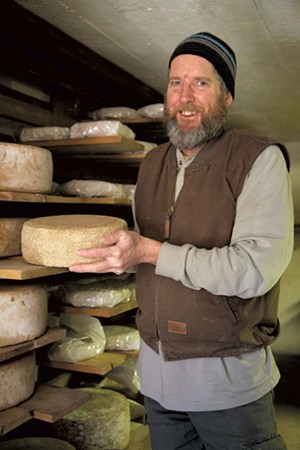

- David Shaw

- Peter Dixon in his Westminster West cheese cave

Goff had the advantage of proximity to Dixon, but many fledgling cheesemakers who come to study at Parish Hill's tiny plant and cave are undaunted by traveling great distances.

Under the name Westminster Artisan Cheesemaking, Dixon teaches introductory and advanced courses on every aspect of cheesemaking, from aging the curds to writing up hazard analysis and critical control points (HACCP) plans.

- David Shaw

- Reverie

Alissa Shethar came from the West Coast to study with Dixon and later settled in Vermont on Bridport's Fairy Tale Farm. She was hardly the farthest-flung of his students. "We've had people from India, Puerto Rico, Mexico," Dixon says.

"We've had several queries [from] Africa and the Middle East," Schaal adds.

"And Palestine," says Dixon.

They're all welcome to come to Westminster West, but Dixon has turned down many opportunities involving travel in order to follow his greatest passion: making his own cheese.

Parish Hill Creamery provides a new lease on life for the Italian-style cheeses that Dixon began making under the name Westminster Creamery, a company he ran from 2000 to 2004. "I continue to love the Italian cheese," says Schaal. "Because of the flavor. I also love that they're not necessarily as fussy."

Though Parish Hill also trades in the tommes and Gruyères so prevalent in the Green Mountains, its finest cheeses have no parallels in Vermont. The Vermont Herdsman is a sharp, Asiago-style cheese. The Suffolk Punch is a creamy, tangy version of Italian caciocavallo — literally "cheese on horseback" — named for its gourd-like shape that resembles a horse and its rider. Its brother provolone, called Kashar, is made in a more typical drum shape.

- David Shaw

The cheese derives from cows that graze the fields of Dixon's alma mater, the Putney School, five miles from the cheese house. Until recently, Parish Hill aged its cheeses at Crown Finish Caves in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, but now he and Schaal endeavor to do all their products' affinage in Westminster West.

The couple's cheeses are all-Vermont products, but relatively few are available here. Parish Hill sells its cheese through Provisions International in White River Junction, and most of it lands in Boston or New York City. The only Vermont retail outlets are City Market/Onion River Co-op in Burlington, Middlebury Natural Foods Co-op and the Grafton Village Cheese store in Brattleboro. Parish Hill cheese also shows up in dishes at the Essex Resort & Spa and American Flatbread in Waitsfield.

Though not many Vermonters have sampled cheeses bearing the name of Dixon's farm, many have tasted the results of his decades of patient study, mentoring and tutelage.

Tom Bivins, executive director of the Vermont Cheese Council, often features Parish Hill's West West Blue, a Gorgonzola dolce-style cheese, at the tastings he hosts. "I think Peter Dixon has definitely been a major component of the growth of cheese in Vermont," he says.

If Dixon is the "king of cheese," he's no Ozymandias, erecting self-glorifying monuments. Instead, his subtle power is felt all over his realm. For most cheese lovers, a taste of his handiwork will suffice to demonstrate that the crown is well earned.

If Vermont has prevailed as a cheesemaking David among Goliaths such as Wisconsin and California, many personalities are responsible for turning it into a force to be reckoned with. Peter Dixon has helped steer the state’s artisan cheesemaking since its first stirrings in the 1980s, but he’s far from the sole pioneer of that movement. The following list is not comprehensive and includes only companies still in operation, thus omitting certain key players, such as the scientists behind the Vermont Institute for Artisan Cheese. But if Vermont had a cheese pantheon, all these makers would be enshrined there.

Mateo and Andy Kehler, Cellars at Jasper Hill

These brothers completed their seven caves in Greensboro Bend in 2008. Now an experienced team uses their setup to age countless award-winning cheeses. The Cellars are also home to the brothers’ own famous Bayley Hazen Blue, Constant Bliss and Winnimere.

Laini Fondiller, Lazy Lady Farm

Her cheese names — think Barick Obama — match this goat farmer’s reputation for taking on the powers that be. Fondiller made waves with her high-profile 1993 battle with Vermont’s ag department over the need for separate areas to pasteurize milk and manufacture cheese. She lost the case, but alerted state officials to a growing need to work better with small farms. Today, combining those areas is legal.

Allison Hooper and Bob Reese, Vermont Creamery

This company was founded in 1984 as Vermont Butter & Cheese Company in Hooper’s barn. Since then, the pair’s goat cheeses have won numerous World Cheese Awards golds and gained the favor of chefs nationally and abroad.

David and Cindy Major, Vermont Shepherd

Many experts say Vermont Shepherd did for sheep what Vermont Creamery did for goats. In 2000, the company’s sheep’s-milk cheese won best-in-show at the American Cheese Society, kick-starting a vogue for the less common curds.

Winfield Crowley, Crowley Cheese

The factory Crowley built in 1882 still operates in Mt. Holly, and his family’s cheesemaking history goes back even farther, to 1824. Crowley’s cheeses were clothbound long before Cabot began borrowing the trick, just one of the debts larger-scale Vermont operations owe to this early pioneer.

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.