- Stefan Hard

- Critter Meadows Farm fire in 2014

On the evening of Sunday, August 2, Dawn and Dan Boucher wrapped up dinner in their home at the edge of the Boucher Family Farm in Highgate. They may have turned on a movie, but Dawn doesn't remember now.

In the background, the couple heard popping noises. "It sounded like tires burning," Dawn recalled afterward. At the time, she didn't think much of it. Minutes later, an ambulance drove up to her father-in-law's house next door.

Then the phone rang: "Your barn's on fire," the caller said. They rushed outside to see smoke coming from the back corner of the farm's main barn complex, which housed calves, pigs and beef cows, two machine shops, and extensive storage for feed, seed and fertilizer.

Dan sped off toward the barn in a Gator. Dawn called the fire department, helpless to do more since she was nursing a broken foot that made walking difficult.

Firefighters flooded in from several area departments. A neighbor drove an excavator over, pulling down the building to keep the fire away from an adjacent workshop. Black smoke billowed in a long column, carried west by the wind.

Sunday drivers stopped to look. "When the silo came down, we had about 40 people in the driveway," Dawn said, "just watching."

She watched too, taking photos of the mayhem.

When the animals started screaming, she had to go inside. "I've never heard anything like it," Dawn said. "I've heard pigs dying in a slaughterhouse, but this was different."

- Stefan Hard

- Critter Meadows Farm fire in 2014

Most of the animals escaped with their lives, but the Bouchers lost eight pigs, five calves and several buildings, totaling $350,000. The thousands of pounds of meat inventory, feed, fertilizer, seed and equipment lost will likely total hundreds of thousands more.

It's not the Bouchers' first fire: The original dairy barn burned in 1979. Now, facing their second fire in as many generations, the family — Dan and Denis, who manage the dairy operation; Gilbert and Patrick, who run the fertilizer company; and Dawn, who runs the cheese and meat business with Dan — convened for a meeting the morning after the burn.

Still in shock and low on sleep, Dawn pondered whether — not how — they would start over. "At 50, you consider these things," she said. But for the others, the meeting was about design. What would they rebuild in the space?

Three separate insurance policies ensure the farm will recover. Last week the area still smelled of burnt feed and manure, but a $20,000 insurance advance jump-started cleanup and rebuilding. "It's coming along," Gilbert said, as Dawn surveyed the turned-up rocks and metal scrap piled in the yard. "Every day we're gaining on it."

In time, the barn will rise again, and the Bouchers plan to build it better and more efficient than before. For now, Dawn has suspended cheesemaking and paused her weekly market trips to Burlington, which will halve 2015 earnings for the meat-and-cheese end of the business.

"We've had to stop everything," she said.

Farming depends on countless moving parts — livestock, machinery, weather, personnel. When essential infrastructure disappears, snags such as damaged fences, tractor breakdowns and animal injuries become complicated ordeals.

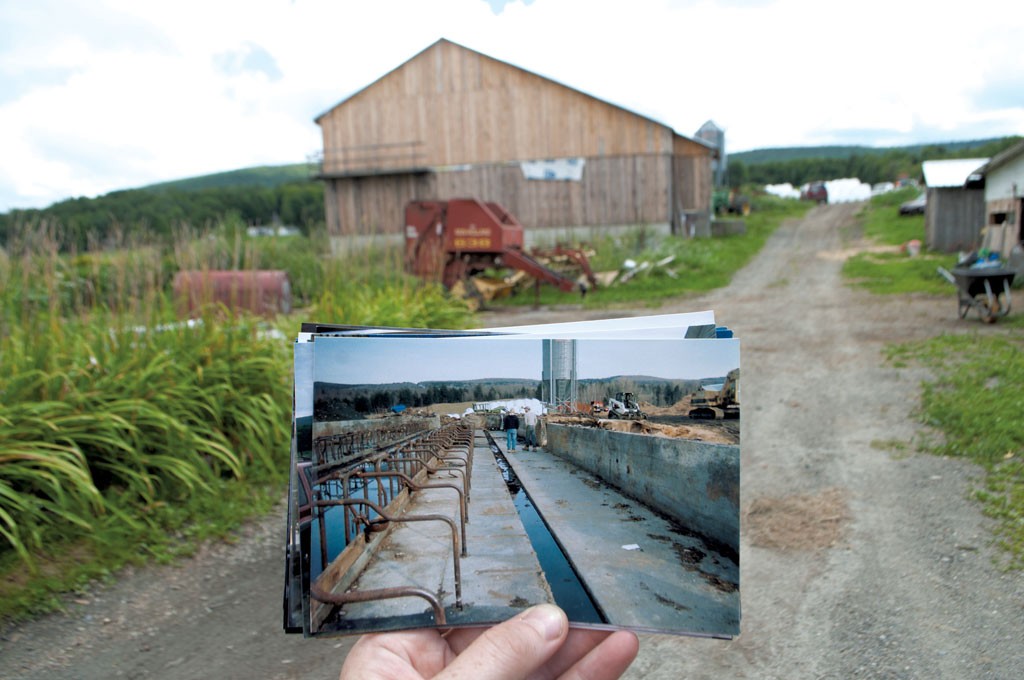

- Courtesy Of Dawn Boucher

- Boucher Family Farm

"Those little things start to bother you," Dawn said. "That last shoe keeps dropping."

State fire safety education and information chief Micheal Greenia says many farms never recover. "Nothing can bring a farm to its knees in a single, decisive blow faster than a fire," he said in a phone interview.

Greenia is a member of the Vermont Barn Fire Prevention Task Force, a group of farmers, firefighters, insurance workers and reps from state agencies, the University of Vermont Extension and the state's congressional delegation that works to educate farmers on fire prevention and mitigation.

Hard data on barn fires are tough to pin down, but Greenia estimated that Vermont farms suffered 109 structure fires in 2014. Local fire departments responded to nearly 600 agricultural structure fires between 2010 and 2014.

"We've seen the loss of so many barns and farms to fire in the last 30 years," said task force member Jenny Nelson, agriculture policy adviser to Sen. Bernie Sanders. "You lose your barn, and you really think twice about whether you want to get back into farming."

Anecdotal evidence suggests that many agricultural properties are under- or uninsured. With an aging farmer population, fires can be a death knell for many operations.

In early 2014, Critter Meadows Farm owners Merri and Dan Paquin chose to purchase winter heating fuel over insurance for their Williamstown organic dairy. "[Insurance] was the last thing I felt I could cut," Merri said, wringing her wrists at her kitchen table last week. "I just figured, I could pause it and pick it back up after the winter and we would be OK."

- Hannah Palmer Egan

- Merri Paquin in the new barn

The Paquins bought their herd in the 1980s, then bounced around north-central Vermont, mostly as tenant farmers, until 2007, when they landed at an old dairy in Williamstown. They dubbed the place Critter Meadows and purchased the property a few years later.

Finally settled, the farm began to diversify. They added meat ducks, rabbits and goats to the business. "We felt like, for the first time ever, we were going to be in the clear," Merri recalled. Then, on a frigid March night just days before the ag inspector was scheduled to sign off on the meat operation, the Paquins' barn burned.

The farmers saved 58 of their 117 cattle. Of these — badly burned and ailing from the smoke — 30 perished within two weeks. Twenty-three of the farm's 27 bred heifers, all due to calf the following month, aborted their babies. That spring, the four calves born on the farm were stunted and sickly.

No one conducted a damage assessment (this usually happens during the insurance claim), but the Paquins estimated the loss at more than $500,000.

Merri said representatives from Organic Valley (the farm's milk co-op) and officials from Vermont's ag department pressured her to send the remaining cows to slaughter and buy new stock. But the farmers held tight to what was left of the herd they'd been working with for three decades.

"These animals survived for a reason," Merri said. "We've invested time and money into them. They're part of our family." Still, she added, "you start to wonder, Why not ship them for beef? Would it be more humane? You're torn with those thoughts."

A neighbor offered his barn, and the Paquins moved their cows down the road. Outfitting the building for milking cost $18,000, but it worked as a stopgap measure. Though the barn has no pasture access — a requirement for certified organic milk — the farmers cut fresh grass and bring it to the cows daily. They take them out for exercise and are slowly nurturing the burned animals back to health.

- Hannah Palmer Egan

- Critter Meadow's new barn sitting on the old barn's foundation

Meanwhile, the farmers cobbled together a new home barn on a shoestring budget with the help of friends, family and a hired hand, who was also injured in the blaze.

This spring, seven of the Paquins' eight new calves were strong, healthy heifers that will join the milking stock in years to come.

"At first it was like, Oh, my God, what have I done?" Merri said. "I made a conscious decision to not have insurance."

Apparently, a lot of farmers make the same call. Merri said 114 dairy farmers came to offer support in the days following the fire. Nearly all of them told her that they, too, lacked adequate insurance.

- Courtesy Of Dawn Boucher

- After the fire at Boucher Family Farm

Average insurance premiums for a farm with 115 milkers cost $3,000 to $7,000 per year, according to Kevin Bourdon, a farm safety specialist at Co-operative Insurance Companies in Middlebury. Co-operative is the leading farm insurer in Vermont and, though the company wouldn't disclose how many agricultural policies it carries, Bourdon said they insure "approximately 75 percent of Vermont's existing dairies." Basic math suggests the company covers about 650 of Vermont's 868 milk producers, and hundreds of non-dairy operations.

In the last year, Bourdon said Co-op handled nine barn fires totaling more than $100,000 each, and that average years bring six or seven barn-fire claims. While Co-op is not Vermont's only farm insurer (other companies were similarly mum about their numbers), it seems safe to conclude that when the state's dominant farm insurer handles fewer than 10 of the state's annual 100-plus farm-related structure fires, many of those fires never see an insurance claim.

But not all on-farm structure fires are barn fires, and not all barn fires involve animals. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture's national census, Vermont is currently home to 7,300 farms — more than 6,400 of them non-dairy. In recent years, Maple Wind Farm (vegetables and meat) lost a barn in Richmond, as did Pete's Greens (vegetables) in Craftsbury. But particularly when livestock are involved, fallout from the fire can cause farms to fail long after the smoke clears.

Earlier this month, Organic Valley moved Critter Meadows' milk onto a nonorganic truck, citing the Paquins' lack of pasture access as a breach of organic practice. The co-op will reassess the farm on October 1, but if the family can't finish the milk room, pump room and a four-stall milking area in their new barn, it could lose its primary source of income.

That's a tight deadline, and Merri Paquin is rethinking her business model. She's looking for other co-op options to pursue if they can't stay with Organic Valley. She's researching on-site processing that would enable Critter Meadows to sell milk independently. And they're chipping away at the new barn that will bring their cows home. "If we're making progress every week," Merri said, "then we're making progress."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.