- Caleb Kenna

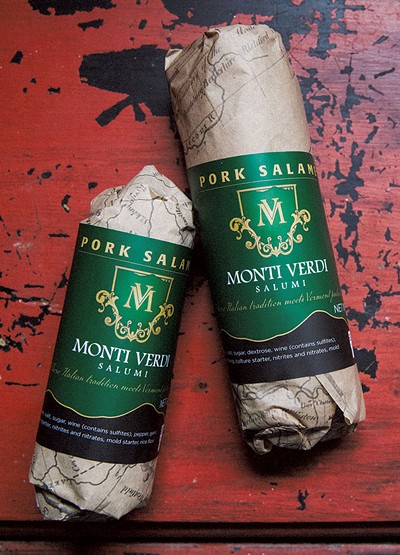

- Monti Verdi salami curing at the company's Middlebury production facility

Around the wooden farmhouse table, a small group chatted in English and Italian, sipping wine and espresso and nibbling on slices of sweet, lard-enriched pizza dolce cake and salami made with the farm's pastured pork.

Despite appearances, this recent afternoon gathering wasn't in Italy but at Agricola Farm in Panton.

Italians did outnumber Americans at the table, though. Agricola co-owners and partners Alessandra Rellini and Stefano Pinna, originally from northern Italy, were hosting the regional consul general of Italy, Federica Sereni, and two of her colleagues. The Boston-based trio was on a tour organized by the Vermont Italian Cultural Association, a nonprofit dedicated to preserving and promoting Italian culture in Vermont.

Rellini, 47, and Pinna, 33, live and work together on the 60-acre former dairy farm where they raise pigs, sheep, chickens and ducks. They also throw multicourse, farm-sourced Italian dinners and sell a variety of farm-grown and farm-made foods, including their Monti Verdi Salumi.

The farmers and four team members manage every step of the process, from breeding the pigs to hand-tying the salami. The latter takes place in their small U.S. Department of Agriculture-inspected production facility in Middlebury. Within the next month, the Monti Verdi team is poised to expand its cured meat line beyond salami.

"It is a lot — between the farm and the salumeria," Pinna acknowledged.

"But thank God we did it," Rellini added. "Fresh pork was not going to cut it financially."

- Courtesy Of Clare Barboza

- Alessandra Rellini and Stefano Pinna with their heritage-breed, pastured sows in 2020

Though they still sell some fresh and frozen pork directly to consumers and through local stores, the farmers have been making salami from their pastured animals under the Monti Verdi label since 2019. The name is a nod to both their heritage and their current home in the Green Mountain State.

In October 2021, more than 150 donors contributed to a successful $33,000 crowdfunding campaign to support the next phase of Monti Verdi's salumi business: curing whole cuts of pork.

Salumi, the Italian word for cured meats, encompasses salami made from ground meat and cured in sausage-shaped casings. It also includes cured whole muscles, such as pork shoulders and fresh hams, which become sliced meats such as coppa and prosciutto, respectively.

Any day now, Rellini and Pinna expect equipment and USDA approval of their new processing plans, but it will be a while before people can taste those products. Their salami cure for 45 days; the whole-muscle meats take four to nine months.

"It's a very slow process," Rellini conceded. "It obviously affects our bottom line."

But the farmers take it slow for good reason. With Monti Verdi, Rellini and Pinna aim to honor time-tested Italian salumi traditions and to develop a business model that works for small-scale, sustainable agriculture in Vermont.

Rellini and Pinna have maxed out Agricola's acreage, raising 160 to 180 pigs annually. It takes 10 to 12 months to raise their heritage-breed, pastured pigs from birth to slaughter weight — 220 to 280 pounds. That's about twice the lifespan of a typical American commodity pig.

Their growth will also involve the slow process of developing partnerships with other Vermont farmers to source more pork raised to Monti Verdi specifications.

They send 10 to 12 pigs to slaughter monthly. "Our goal is going to be 50 pigs a month in three years or so," Rellini said. "We are talking about training other farms to do the same things that we do."

Rellini and Pinna expect their value-added product line to allow them to pay farmers at least four times the going commodity pork price.

- Courtesy Of Clare Barboza

- Agricola Farm in 2020

So far, the couple has funded Monti Verdi's startup with $350,000, mostly from grants. In 2020, they received a $204,000 USDA value-added producer grant, for which Rellini and Pinna applied with technical and business planning support from the Vermont Housing & Conservation Board's Farm & Forest Viability Program.

"They have built an amazing business slowly and deliberately," said Farm & Forest director Liz Gleason. She elaborated that deep knowledge of farming and meat curing and careful evaluation of the market opportunity distinguish Monti Verdi's approach. "Value-added is an incredibly important part of the working landscape," Gleason said.

Rellini is an unlikely agricultural entrepreneur. She first came to the U.S. at age 15 as an exchange student in Ohio. After briefly returning to Italy, she came back to the U.S. for college and graduate school. She moved to Vermont in 2007 for a job at the University of Vermont and has been an associate professor of clinical psychology since 2012.

The teacher and researcher did not plan to add a second full-time career, but, she said, "When I came here, like every Italian, I think you miss your food tremendously." Everyone around the Agricola Farm table heartily agreed.

Rellini began by raising a few backyard pigs. In 2012, she returned to Italy to do research as a Fulbright scholar. "On the weekend, I would go and hang out with the farmers and norcini to learn," she said.

Norcini, Rellini explained later, are specialized butchers for cured meats named for the town of Norcia in Umbria.

She founded Agricola in Williston in 2013 and moved to Panton in 2014. "Now, boom, I have 60 acres. If you have 60 acres, you need to have more pigs," Rellini said. "And then I needed more help."

In 2015, she advertised for a farm assistant. Pinna, who had just graduated from the University of Turin with a master's degree in agricultural science, stumbled upon the opportunity.

"I found the ad in the dark web," he joked, "and I ended up in the dark Vermont in a tiny, tiny town."

Pinna wanted to learn English and see a different side of agriculture, he explained. After three months at Agricola, he went home only to soon return — "for love," he said, smiling over at Rellini. "We like working together."

- Courtesy Of Clare Barboza

- Monti Verdi salumi

Replicating the Italian approach to salumi in Vermont under USDA food-safety requirements has proven challenging, the couple noted. Overall, Rellini said of the Monti Verdi line, "I think it's a good product. It's as authentic as we are allowed to make."

"Are the rules very different?" asked Sereni, the Italian consul.

"It's been a nightmare," Rellini responded before hedging. "Not a nightmare, but it's been very complicated to navigate."

Pinna gave a quick rundown on the four varieties of salami the visitors were sampling. Classico recently won a 2022 Good Food Award. "We make it the traditional Piedmontese way with garlic, nutmeg, black pepper and this wine, barbera," he said, gesturing to the bottle on the table.

Aromatico is based on a traditional Tuscan Finocchiona with fennel and nontraditional smoked paprika — "a blasphemy," Pinna said, laughing. Piccante, a Puglian recipe from a friend's grandmother, includes Calabrian peppers. Delicato is made with wine infused with whole juniper berries, cloves and nutmeg, along with dried herbs.

These kinds of salami are among the foods she missed the most from Italy, Rellini said later. Pinna recalled taking summer Sunday hikes as a child with his family in the Alps near Turin.

"You walk by all these little huts where they're making and aging cheese. You just knock on the door and they cut cheese for you out of big wheels two feet around," he said. "You can get salami, too. It's not really USDA-compliant," he added, dryly.

On April 11, a week after the farm visit, Pinna was working with Monti Verdi senior butcher Josh Glosser in the 1,000-square-foot, USDA-compliant salumi facility on Middlebury's Exchange Street.

They receive five pigs every other week from their contracted slaughterhouse. Starting with half carcasses, the butchers remove and package what will be sold as loins, chops, ribs and other cuts.

The shoulders and fresh hams are hung in the cooler and processed gradually for salami. It takes all day to break down six or seven of them by hand. "We need to separate each individual muscle," Pinna explained as he worked. The butchers also carefully select the fat. "The fat closer to the skin is harder; that is the one we want for salami," he said.

Softer fat smears when ground and, because fat repels water, if it is dispersed too much, the salami will be dry and crumbly.

- Caleb Kenna

- Tying salami

Just by looking at a carcass, Pinna can tell what the pigs have eaten. During the growing season, Agricola's pigs get 25 to 30 percent of their nutrition from pasture. The also eat some corn, spent grains from local breweries, oats, wheat fiber, and a smattering of other grains, seeds and legumes.

The animals' diet is critical. Especially with the simpler whole-muscle cures, "all those flavors from the fields, you can taste them," Pinna said. Raising pigs from birth is more work, he added, "but we have more control on every step."

After the meat and fat are seasoned and mixed and the salami stuffed and tied, they spend a week in temperature- and humidity-controlled curing cabinets bought in Italy for $30,000 each. Low-tech pieces of lined shower curtains cover the glass doors to keep out light. Another several weeks in a walk-in aging cave pass before the 4- to 6-ounce salami are ready to sell for $7 to $11.75.

Among the Vermont retailers who carry Monti Verdi salami are the Dedalus wine shops and markets in Burlington, Middlebury and Stowe. Dedalus market buyer Rich Morillo has a deep Italian food background after a decade working for Di Bruno Bros., a specialty grocery founded by Italian immigrants in Philadelphia in 1939.

Morillo's first tastes of Monti Verdi salami convinced him that Dedalus should carry them. A visit to the farm was the cherry on top.

"It's a pretty magical place and incredibly well thought-out," Morillo said, "from the genetics of the pork to a real commitment to thinking holistically about how to farm sustainably."

He's excited to taste the forthcoming products. "A Vermont prosciutto would be nuts if they execute it as well as everything else they do," Morillo said.

Rellini and Pinna have every intention of meeting his expectations. They dream of the day when Monti Verdi Salumi can support a network of Vermont farms producing pork in a way that is sustainable for the Earth and economically sustainable for the farmers.

Perhaps, Pinna mused, Monti Verdi's version of the famed prosciutto di Parma might be called prosciutto di Champlain.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.