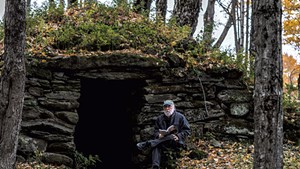

Located on the outskirts of Northfield, the place locals call the Devil’s Washbowl is a basin-shaped terrain of streams and caves full of fallen, moss-covered rocks. Some people might go there for a hike. Burlington’s Joe Citro went in search of Pigman.

And just who is Pigman? His story came to light more than a decade ago, when Citro was giving a talk in Northfield. A man by the name of Jeff Hatch stood up to ask if the intrepid local folklorist, author of several books about Vermont legends, had ever heard of a creature that terrorized his high school dance back in 1971. On that memorable night, a group of boys returned from a sandpit adjacent to the cemetery behind the school — where they’d stashed some beers — “scared and literally crying,” recalls Hatch. “They were really shook up.”

The whole group reported having seen a humanlike creature covered in white hair bound over the hill, kicking up sand. When Hatch and other partygoers followed the pack to the pit, “of course we didn’t see anything,” he says. Except for cloven markings in the sand.

Around this same time, Hatch says, “people’s dogs and cats started coming up missing.” One resident of Turkey Hill, a part of Paine Mountain, reported hearing something rattling around in his trash can. According to Hatch, the fellow expected to shoo away raccoons. Instead, when “the thing stood up it was all white and covered in hair.” Reports gathered by Hatch place the creature at somewhere between 5-foot-5 and 6 feet, with a piglike snout and beady eyes.

Around the time of the first Pigman sightings, rumor has it a fair-haired teenage boy disappeared from Darby Farm in Northfield. Some say he became Pigman, others that he became Pigman’s dinner. No one seems to have a name for him.

Is Pigman a monster, a farmboy gone feral, or a figment of country folks’ intoxicated imaginations? Whatever his status in reality, he’s one of the stars of Citro’s new book, The Vermont Monster Guide, which features illustrations by his longtime friend Steve Bissette. The book showcases 60 more bizarre beasts, and was conceived as a way for Citro and Bissette to collaborate for the first time since 2000’s The Vermont Ghost Guide.

Bissette, now an instructor at the Center for Cartoon Studies in White River Junction, is well known to modern horror and comic fans worldwide. He’s the nice guy from Vermont who collaborated with notoriously volatile British graphic-novel god Alan Moore (Watchmen, V for Vendetta). Together, Moore and Bissette reinvented Swamp Thing in the nihilistic 1980s series The Saga of the Swamp Thing, and Bissette published the original versions of Moore’s From Hell and Lost Girls in the noted anthology series Taboo, put out by his company, SpiderBaby.

On his own, Bissette created the series Tyrant, a wordless journey through the life of a T. Rex. He did all this while raising his two kids in southern Vermont, using FedEx and, later, high-speed Internet to collaborate with writers and artists around the world.

Bissette met Citro at a 1987 Horror Writers Association convention; they were introduced by Stanley Wiater, a writer whom Radio-TV Interview Report has called “the world’s leading authority on horror filmmakers and authors.” Citro and Bissette — who have similar bushy beards and share a fondness for hats — were both lifelong Vermonters: Bissette grew up in the Duxbury area; Citro in Chester.

Their tastes aligned. Independently, both men mention their youthful obsession with a 1940 Scholastic Paperbacks collection of esoterica called Strangely Enough! by C.B. Colby. (Bissette says its images strongly influenced the “raw, rough and ready” art style that he used in Monster Guide.) Both men are longtime fans and reliable encyclopedias of horror movies, from The Cat and the Canary (1927) to The Orphanage (2007). As Citro puts it, “We were kind of growing up together, but we never really knew each other.”

Bissette came up with the idea of a monster book. Citro protested at first, fearing there would not be enough creatures for the collection. But, realizing he had already profiled multiple monsters in his earlier works, he wrote five entries on spec. Bissette, meanwhile, created several original ink-and-brush critters on a cardboard background. Then he used his prior experience to seek and negotiate with publishers. (Neither man has an agent.) Bissette says he knew he had a score when Richard Pult of University Press of New England told him his younger son “had taken photocopies of the pictures to bed with him.”

That’s exactly the audience Bissette had in mind. With UPNE’s release of the book, “We hope that we mark and traumatize a whole generation of Vermont kids,” he says.

His illustrations are on the right track. With the motto “nature is messy” at the back of his mind, Bissette proves it with such images as Dummerston’s Vampire Vine creeping into coffins, eating the eyes and binding the limbs of the dead. Flies buzz around the heads of his trash-swilling Pigman and Bloomfield’s pocket-sized fuzzy dinosaur, Steggy. “I try to capture that buggy, messy outdoors in Vermont,” explains Bissette. “I tend to put in flies and other things that people link to my style.”

Citro came up with the idea for the striking cover, which pictures Champ rising from Lake Champlain in the form of a question mark, dotted by the reflection of the moon in the water. Bissette completed the ink-and-brush drawing, but another cartoonist, Cayetano “Cat” Garza — hailed as a pioneer of web comics, and now an advisor and web specialist at the Center for Cartoon Studies — added the shimmering, nearly incandescent color.

Though Bissette says his process involves “doing research, then forgetting what you researched and start[ing] fresh and in a lot of cases just pull[ing] it out of my ass,” Citro claims his friend does “really meticulous research.”

Citro himself certainly does. From August 2008 to the book’s completion in May 2009, he solicited stories from every historical society in Vermont. He acknowledges the help of the Green Mountain Folklore Society and the University of Vermont Archives of Folklore and Oral History in preparing the book, and he boasts a massive personal collection of Vermont maps and history volumes.

But Citro does a lot of his research by just talking to folks. “Since I’ve become recognizable as someone interested in these sorts of things,” he says, “people bring me stuff, and that makes it really easy.”

Halloween is a busy time for Citro. Nearly every night of October brings another speaking engagement for Vermont’s emperor of the esoteric. With a packed schedule that includes a show in his native Chester, Citro is rarely home when autumn leaves start to fall. But he’s glad to share his passion — and, more importantly, to get fresh material.

It was at such a gathering that Citro met Jeff Hatch, now 54. Though the Northfield resident has never personally spied the beast, Citro refers to him as “the Pigman historian,” adding, “It’s very likely that, if not for Jeff Hatch, the story of Pigman would never have gotten out at all.”

When he was in high school, Hatch’s favorite “party” spot was Bean’s pig farm, an abandoned assemblage of barns that was once home to what he describes as “500-pound monster pigs.” It was not uncommon, he says, to see “something” run into the brush while he was hanging out there.

Just up the road is Devil’s Washbowl, where Hatch had his most immediate Pigman experience. He describes it as “a nice drive, especially at night. The trees overhang the road and it’s dark and creepy — the perfect place for this story to take place.” Hiking the area at night, he believes he found what he was seeking: “Pigman’s lair.” A bed of straw in one corner was surrounded by piles of small animal bones, “like cats’ and dogs’.” That night and on other occasions, Hatch says he heard “a real high-pitched screech” that “would kind of circle you.”

Naturally, Citro had to see this place for himself. He even promised to take a reporter along on his Pigman hunt, but a broken toe and an assuredly coincidental bout of swine flu derailed the plan. Citro does show Seven Days photos he took in the Washbowl, which he says “do nothing to convey its utter weirdness.” Its temperature, he says, is “misaligned with the rest of the world.”

But Pigman failed to show his face, or howl, when Citro was around. “I … felt something weird, but nothing really tangible,” the writer admits. “I was just so programmed at that point that there would be something weird, I was on my guard.”

Though The Vermont Monster Guide lists Pigman as active from 1971 to the present, neither Citro nor Hatch is aware of recent sightings. As the book brings Pigman publicity, that may change — Citro suggests, “He’s much more likely to be heard or spotted if people know about him.”

Does that say something about the power of suggestion in shaping a legend? Citro shies away from debunking or strenuously doubting the tales he collects, whether they concern Pigman or “long-leggedy cats” that an acquaintance spotted at the site on Shelburne Road now occupied by KFC. He says that, while Pigman may or may not exist, “the fear and wonder [of people who saw him] was legitimate,” and he’s proud to “have the Pigman exclusive.”

Not that Citro doesn’t make any judgments — he says he’d place the “Porcine Peculiarity” somewhere in the middle of his “continuum that starts with the absolutely true and ends with the fanciful, like the Man-Eating Stone.” The Monster Guide also covers “monsters” that are perfectly real, just odd enough to be startling. There’s an entry for catamounts, once thought to have vacated the state. Citro believes he’s seen one of the big cats himself. He also calls Champ “a smidgen away from being real,” noting accounts he’s heard from reliable friends and the work of bioacoustician Elizabeth von Muggenthaler, which suggests there’s something strange in the lake.

But never mind whether they exist — which monster is the coolest? Bissette, whose high school nickname was Spider, gravitates toward lower life-forms such as Insectosaurus, a giant inchworm reported in Alburgh in the 1980s. Citro says naming his favorite monster “depends when you ask me,” though he does mention Sidehill Cronchers as a recent highlight of his talks. The deer/boar hybrids, which have been spotted on Mount Mansfield and in Bridgewater and Stockbridge, are said to have shorter legs on one side to help them navigate their mountainous landscapes. This adaptation makes coupling difficult; hence the species’ rarity. “That cracks me up,” says Citro.

Not that the business of tall tales is all laughs. Citro considers himself a conservationist who thrives on “bringing the stories back from the dead and keeping them alive.” That’s why he tells ghost as well as creature stories, though he admits the former interest audiences more than they do him. (Citro’s not a fan of what he calls the “new spiritualism” that has made the occult popular again.) He tells audiences at his shows that “just listening keeps [the tales] alive. They tell part of our history and who we are.”

For their next collaboration, Citro and Bissette are currently shopping a monster book that covers the whole U.S. Citro is quick to note that he will avoid widespread classics such as lake monsters and Bigfoot variations, preferring to convey the “shared sense of place” that imbues each local monster.

Which cryptic critter will represent Vermont? Citro tips his hat to the one who never did show his face to the researcher in Devil’s Washbowl. “I don’t know,” he says with a shrug. “It might be Pigman again.”

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.