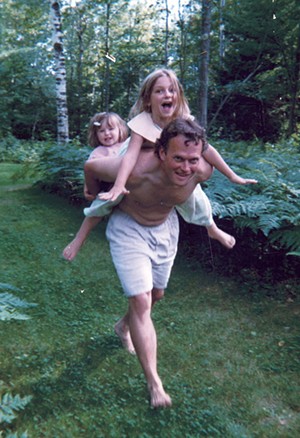

- Courtesy

- Willem Jewett and his daughters, Anneke (front) and Abi circa 2002

In the days before Willem Jewett (August 23, 1963-January 12, 2022 ) died last winter, he was too sick to eat more than a few nibbles or drink more than a sip. His wife was concerned that Willem, who was terminally ill, might be unable to swallow the physician-prescribed medication he intended to drink to end his life.

When the palliative care doctor arrived at the Jewetts' Ripton home on the afternoon of January 12, Ellen McKay Jewett checked with her husband: "Do you really want to do this?" she recalled asking him.

"Forza," he answered. The Italian word means "force" or "strength"; it also means "Let's go."

Willem swallowed the four ounces of medication, a multidrug concoction, in one gulp from a Citizen Cider glass, Ellen said. (He wondered why he couldn't drink a good beer with it.) Then he settled himself on his pillow and got comfortable in his bed. He formed the shape of a heart with his hands and pointed the symbol at his two daughters. Family members on the bed with Willem held his hand and touched him in his final moments.

"It was the most graceful, courageous, beautiful way to go," Ellen said.

Willem died in about 15 minutes as his brother, Joe, a professional violinist, played the third movement of Johann Sebastian Bach's Violin Sonata No. 3 in C Major. Willem had asked his sole sibling to "play me out."

"It was kind of challenging," Joe, 63, said. "He's my brother dying, and I'm playing music."

But the people who assembled at Jewett's house that winter day were honoring the choice and wishes of their husband, father, brother, friend and patient.

"We were doing what we knew he wanted to do. He had made his intentions clear, and things moved along," Joe said. "It just proceeded as we knew he wanted it to go."

Willem, who died at 58, was an Addison County state representative from 2003 to 2017. During his term as house majority leader from 2013 to 2014, he helped enact Act 39 – the Patient Choice and Control at End of Life Act — which gives terminally ill Vermonters with a prognosis of less than six months to live the option to end their lives with prescription medication. Willem's decision to utilize the law roughly 14 months after he was diagnosed with mucosal melanoma was consistent with "who he was as a human," Joe said.

"He was very practical," Joe said. "It was all about moving forward with plans and doing things. He was a real doer."

Willem was an attorney, a lawmaker, a father, and a driven and talented athlete with a passion for cycling and skiing. He was captain of the ski team at Bowdoin College in Maine. On a snowy day in 1994, he showed up for his job interview at a small Middlebury law firm on a bike. Years later, he occasionally pedaled his road bike from his Ripton home to the Statehouse — pushing the pace the whole hilly way. He was a gravel biker before gravel biking was a thing.

"Willem was one of these people: If he was going in, he was going all in," said Mike Hussey, his close friend and manager of the Middlebury College Snow Bowl. "If he had to sort something out, he'd get on his bike or put his skis on and crank his heart rate up. For a seemingly unassuming guy, he definitely pushed the pace."

He and Ellen, his second wife, had been together for four years and married just six months when he died. They got engaged in November 2020, two weeks before his cancer diagnosis. Their relationship would never have blossomed, she said, if plans for their second date had gone differently. The two had decided to go snowshoeing, and when Willem asked Ellen how long she wanted to be out, she replied, "About two hours." She later realized that if she'd answered "half an hour," their dating would've faltered.

They snowshoed that February day in 2018, and then Willem — a marvelous cook, family and friends said — served Ellen potato-leek soup and toasted cheese sandwiches made in his fireplace. That was that.

"I felt like I had found the needle in the haystack," said Ellen, 59, administrative program coordinator for the Charles P. Scott Center for Spiritual and Religious Life at Middlebury College.

In their four years together, they traveled to Iceland and Utah, rowed an Adirondack guide boat on the Connecticut River after one of his cancer treatments at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center and toured the countryside on motorcycles. They rode bicycles, too: On an electric bike, she barely kept pace with Willem on a nonmotorized one.

"He was the guy you always wanted in the room," Ellen said. "The [person] with the energy and the sparkle and the wit and the know-how and the hard work."

Willem was born in Larchmont, N.Y., and raised in Westport, Conn., the second son of Marianne van Hoorn and Joseph Jewett. He was an adorable baby, his brother said, a little boy that people oohed and aahed over. The year he was born, his parents bought four acres and built a cabin on Tucker Hill Road in Waitsfield, where Willem developed his love for the outdoors and recreation.

He and his family spent weekends and vacations in the Mad River Valley, where the choice on a winter Saturday was whether to ski at Mad River Glen or Sugarbush Resort. (Mad River usually won out.)

- Courtesy

- Willem and Ellen Jewett (center) with family and friends at their June 2021 wedding

Willem's father was a chemical engineer who commuted to New York City for work; he died when Willem was 9. His mother remarried about a year later. In the 1970s, Willem left home for the Loomis Chaffee School, a day and boarding prep school in Windsor, Conn. After college, he moved to his family's Waitsfield cabin, where he worked seasonal jobs — pounding nails and teaching sailboarding in the summer, coaching skiing in the winter. He then headed to Portland, Ore., to attend Lewis & Clark Law School and graduated in 1994.

He returned to Vermont, and Dick Foote hired him to practice in Foote's Middlebury law firm. They worked together for 23 years, during which time Willem raised his daughters with his first wife, artist Jean Cherouny, and served in the legislature.

"He was very committed to his own values," Foote said. "And they were made manifest to anyone who worked with or against him."

When Act 39 was introduced, the proposed legislation was "high profile and sensitive," said Shap Smith, a lawyer in Morrisville who was speaker of the house at the time. Disputes arose between the House and Senate and the leadership of both bodies, he said. Passage of the bill involved "a very complicated negotiation," according to Smith.

"Willem, me and the assistant majority leader were all involved on a day-to-day basis in making sure that the bill could pass," Smith said. "I think that it was an issue that [Willem] really felt strongly about, from a choice perspective."

Almost 10 years later, as Willem faced his own death, he advocated for changes to the law in the last months and days of his life.

"I talked to him two days before he died," said Rep. Ann Pugh (D-South Burlington), chair of the House Committee on Human Services. "The things he felt strongly about, he let us know."

Modifications to the bill included removing a two-day waiting period to receive the prescription and allowing one of two doctor visits to occur via telehealth rather than in person.

Willem's friend Sen. Ruth Hardy (D-Addison) worked on the revised bill. In her January 26 Statehouse blog, posted two weeks after his death, she wrote: "I asked my senate colleagues to vote for the bill in [Willem's] memory."

In April, Gov. Phil Scott signed the bill into law.

Though it's not necessary for a doctor to be present when a person ingests the medication, Diana Barnard, a palliative care physician in Middlebury, was at Willem's house.

"He was Willem," Barnard said. "He was resolute and determined and at peace with what needed to happen."

Act 39, also known as the Death With Dignity Law, can offer comfort and security to people who are nearing the end of their lives, Barnard said, including those undergoing treatments with uncertain outcomes and debilitating side effects.

"Most people that I see want to live as long as possible and as well as possible," Barnard continued. "Most people also want to have some kind of say or control over what happens at the end.

"When we have an opportunity to see that death is coming and plan for it and have the most important people in our lives present," she added, "that truly is a spiritual moment."

After Willem died, he remained for six or seven hours in the house he had designed and helped build, Ellen said. His family changed his clothes and tucked him back into bed. People came and went from his bedroom to visit with him. They lit a candle by his bedside and made a fire in the fireplace downstairs. They played music and ate food.

When the cremation service staff arrived, six friends and family members carried Willem downstairs.

"They were six of your strongest warriors," Ellen said. "And he was like a chieftain."

His family put a hat on Willem before he was taken out into the winter night.

Living and Dying Together: Calais Couple Opts for 'Death With Dignity'

- Courtesy

- Elaine and Stanley Fitch

The summer day when Stanley and Elaine Fitch died at their Calais farmhouse was a "very loving experience," their eldest daughter, Donna Fitch, said. The couple were with their three daughters, their daughters' partners and some of their grandchildren. Stan was 99; Elaine was 93. They were seated in their kitchen, looking out the window at Spruce Mountain in Plainfield.

"They sat together every day in their two chairs," Donna said. "And that's where they died."

On August 30, in the final act of their 71-year marriage, the Fitches used Vermont's Patient Choice and Control at End of Life Act to end their lives. Known as the Death With Dignity Law, it allows terminally ill patients with less than six months to live to choose to die with medical assistance.

The Fitches were pillars of their central Vermont community, where he was a farmer and she was a teacher. They raised their kids in a Kents Corner farmhouse situated on a rise between a sawmill and a cemetery — the same farmhouse where Stan was born in 1923.

They died by drinking physician-prescribed medication, mixed with apple juice, that was delivered to their house by a Rutland pharmacist. Dying together "meant everything" to her parents, Donna said. Neither had to watch the other die nor live without their partner of seven decades.

"They both wanted this option," Donna said, "so it just made sense for them to do it together."

The Fitch family heard about the Death With Dignity Law from a friend, Donna said. They raised the option with Stan and Elaine's hospice nurses. In accordance with the law, the Fitches had appointments with two doctors, who affirmed their eligibility for Death With Dignity. Though the law allows one appointment to be remote, both physicians made house calls to the Fitches, according to Donna, who declined to share her parents' specific diagnoses.

"We're surprised that more people don't know about it," Donna, 70, said. "We're curious why it isn't offered as an option. We really hope that more people can know about this."

According to the Vermont Department of Health, from May 31, 2013, through October 7, 2022, 163 Vermonters used the state's Death With Dignity Law. A fraction of that number died from "underlying disease" before self-administering the medication, according to the health department. In January, Willem Jewett, a lawmaker from Ripton who helped enact the law, made use of the law to hasten his own death. (See page 44.)

The Fitches, whom Donna described as open-minded people, had made it clear to their family that they didn't want to linger. They also didn't want to be a burden on their daughters, Donna said.

Their last day alive was full of "love and laughter and sharing of memories," Donna said. "It was an absolutely wonderful experience."

"They were not scared at all" to die, she said. "They were so ready. They had a long, wonderful life, and they were loved by the community."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.