- Courtesy

- Cassandra Johnston (right) with her mom, Susan Duchnycz

Cassandra Johnston is hoping chemotherapy helps her beat breast cancer and live a long, fulfilling life. The 38-year-old emergency planning manager from Clifton Park, N.Y., said the treatments she's been receiving for three months are "rough" but represent her best shot at getting healthy.

"With stage III, you don't know which way it's going to go," Johnston told Seven Days last week.

If the battle doesn't go her way, Johnston said, she needs to know she will have some control over how she dies, something the State of New York does not give her.

"When you read all the terrible stories about ways that people have suffered, to be denied medical aid in dying is pretty upsetting," she said.

She's urging New York lawmakers to pass a bill allowing physician-assisted suicide in her state. If they don't, she's hoping Vermont will open its doors to nonresidents such as her.

"I'm keeping my fingers crossed every single day that Vermont lawmakers really view us as people who are suffering," she said. "We're being denied this right in our own states, and we're desperate."

A decade after Vermont passed its landmark medical aid-in-dying law — known as Act 39 — the state is considering lifting the residency requirement so terminally ill people from other states could travel to Vermont to use it, too. Advocates say the change is needed by people who can't receive life-ending medication in their home states.

"I don't think it's fair to allow a state border to decide who gets care and who doesn't get care," Toni Kaeding, cochair of the board of the nonprofit Patient Choices Vermont, told senators last week. "I think it's not fair to deny out-of-state patients access to the peace that is possible through Act 39."

The bill, H.190, received approval in the House of Representatives in February following a unanimous vote in the House Committee on Human Services. It's now under consideration by the Senate Committee on Health and Welfare, which is expected to back the change this week.

"There is simply no justification to put residency parameters on end-of-life care," the bill's lead sponsor, Rep. Rey Garofano (D-Essex), told colleagues.

The push to lift the residency restriction has broad support from lawmakers, owing to a potent combination of advocacy and legal pressure by groups trying to lower barriers for terminally ill patients seeking such care.

It's also taking place against the backdrop of a national abortion debate that is underscoring the deep inequities in health care options for women based on where they live. While deep-red states are outlawing abortion, Vermont has enshrined it in the state's constitution — and is advancing legislation to protect health care providers who treat patients from other states.

Vermont was the first state in the nation to pass an assisted suicide law through a legislative process. Oregon and Washington passed similar laws through ballot measures, and a Montana court authorized the practice. Today, 10 states and Washington, D.C., allow what advocates call "death with dignity" in some form.

The national advocacy group Compassion & Choices filed a federal lawsuit in 2021 over Oregon's residency requirement, arguing that it unfairly discriminated against people from other states. The state settled in 2022 and agreed not to enforce the residency provision.

The organization then set its sights on Vermont, where regional health care providers such as the University of Vermont Health Network, which has hospitals in New York, serve many patients across state lines.

The group sued the state in August, arguing that its residency requirement was unconstitutional because it denied residents of other states equal treatment under the law. It sued on behalf of Lynda Bluestein, a cancer patient living in Bridgeport, Conn., and Diana Barnard, a UVM hospice doctor in Middlebury who also treats patients living New York.

The state settled the case last month, agreeing to allow Bluestein to receive end-of-life care in Vermont if she followed all the law's requirements, including receiving care in the state and, if needed, taking the fatal dose here.

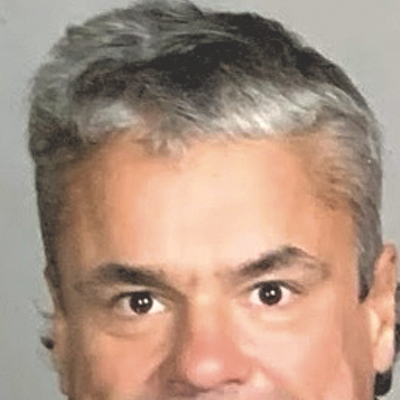

- Courtesy

- Cassandra Johnston

The law, officially known as the Patient Choice and Control at End of Life Act, already contains significant safeguards. To use the law, a person must be at least 18 years old, have less than six months to live and be able to make their own health care decisions. The person also has to make the request of a Vermont doctor twice, at least two weeks apart, and in writing before two witnesses. A second consulting doctor must also confirm the patient's terminal diagnosis, and the patient must be able to take the drugs themself.

If all those criteria were met, then a pharmacist could fill the prescription, typically a mix of five drugs. When mixed with juice, the cocktail is swallowed by the patient, who goes to sleep within 10 minutes and in most cases dies within two hours, Kaeding explained.

The legal settlement only applies to Bluestein, who would have to travel to Vermont to use the drugs. For it to apply to others, the residency requirement would need to be lifted by the legislature. The legal settlement requires the state Department of Health to support such a change this session. David Englander, a department analyst, told senators that Act 39 is the only health care law with a residency requirement and that removing it was appropriate.

"Being able to receive medical care irrespective of zip code is a necessary component of health equity," he said.

Since the law first passed, 173 people have been prescribed drugs by Vermont physicians to end their lives, according to Englander. Most of those — 77 percent — had cancer, while others had neurodegenerative disorders such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS, according to a 2022 state report. About 60 percent of the patients used the drugs they were prescribed, while most others died without taking them, the report said.

The law was updated last year to allow consultations with doctors by telemedicine and to remove a final 48-hour delay before a prescription could be written, which advocates said was burdensome.

Opposition to the current bill appears limited. Mary Hahn Beerworth, executive director of the anti-abortion group Vermont Right to Life Committee, argues that the in-state restriction is important.

The legislature was "deeply divided" about the issue back in 2013, and "legitimate and serious concerns" about assisted suicide persist, she said.

"It isn't something that is to be taken lightly, nor is it simple," she testified.

The residency requirement was one of the law's few protections against abuse, and removing it would be a "slippery slope," she said.

"The erosion of safeguards was predicted in 2013, and the question is, will that erosion continue until ... the lethal combination of drugs are available to anyone of any age or circumstance who requests them?" Beerworth said.

In an interview, Beerworth warned of risks, such as vulnerable people being coerced into hastening their death by greedy family members hoping to inherit some wealth, or people coming to Vermont to acquire the drugs only to take them back to uncontrolled settings in their home states.

Betsy Walkerman, president of Patient Choices Vermont, said opponents raised such issues during the yearslong debate running up to the law's passage.

"This law has been in effect for 10 years," she told Seven Days, "and none of their fears have come true."

The idea that Vermont would become a destination for large numbers of people from across the nation looking to end their lives is unfounded, Walkerman said. Patients would still face hurdles such as the expense, finding a physician who would provide treatment and getting a place to stay, she said.

Barnard, the UVM physician and plaintiff in the recent case, agrees that few out-of-staters would take advantage of the process in Vermont, partly because of the difficulty of finding a physician.

"I don't think we have to be overly concerned about opening the floodgates for people coming here for this," she said.

Most people at that final stage of life want to be around family, and the prospect of traveling, potentially multiple times, to Vermont would be a significant barrier, Barnard said.

But some people facing a terminal diagnosis can summon remarkable fortitude, whether to seek extraordinary experimental care or to prepare to die on their own terms, she said. Having such plans in place, in the end, can make their transition more humane, Barnard added.

"Once they know they have that, they can focus more on living well for as long as possible," she said.

By the time Johnston was diagnosed last fall, the cancer had spread to her lymph nodes. Still, she wouldn't qualify to receive the drugs in Vermont even if the residency requirement were lifted. That's because she's receiving treatment that could prove effective.

But she's not going to wait until the disease makes her so weak that she couldn't come to Vermont if needed. As soon as lawmakers act, she said, so will she.

"I don't like to leave things up to chance," she said.

Correction, April 23, 2023: A previous version of this story misreported the House committee that approved the bill.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.