- Matthew Thorsen

- Sandrine Kibuey, Aline Mukiza and Isra Kassim

There's an African saying that if you educate a man, you educate an individual. But if you educate a woman, you educate a nation. To pay homage to Women's History Month, Seven Days spoke with three African women who have made Vermont their home and represent an emerging female leadership in our multicultural community.

The women vary in age and country of origin, but they have a common goal: to make the Green Mountain State a better place to live. And the benefits of their work extend beyond particular ethnic communities. Sandrine Kibuey focuses on improving the living conditions of anyone in need. Aline Mukiza helps young Burundians preserve their cultural identity while adapting to their new home. Isra Kassim brings her strong voice to the antiracism movement. All three are making new history in Vermont.

Giving Hope

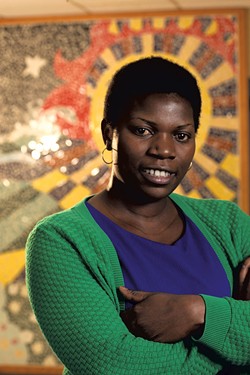

- Matthew Thorsen

- Sandrine Kibuey

Sandrine Kibuey recalls playing with a Rubik's Cube when it first came out in the 1980s. "That was a pain, man, to get the same colors," she says. "But I loved it."

While Kibuey, now 43, no longer plays with the Rubik's Cube, she hasn't stopped solving problems. As the associate director of Chittenden Community Action at the Champlain Valley Office of Economic Opportunity — a job she's had for four years — she says she's in the "crisis sector." Her clients include the homeless, former inmates, refugees and asylum seekers.

"We help people make ends meet when it comes to housing, fuel, food assistance, anything else," Kibuey says. "To find a solution to a problem — this is what I love doing."

The outgoing Congolese, who's been in Vermont for a decade, is one of just a few middle managers in the state's nonprofit sector to have a multicultural background. Yet service providers are more effective when their workplace reflects the diversity of the community they serve, Kibuey says: "For people to come to you, they need to be able to see themselves in you."

Diversity in the Vermont workplace is still "a work in progress," she observes. But as a growing number of children from multicultural families graduate from local colleges, there will be "more [like] me in this position, more in higher positions, I'm sure," Kibuey says.

Kibuey was born in Paris, where her father was a graduate student. After he completed his PhD, when Kibuey was 15, the family returned to Kinshasa, Congo's capital. In 1998, Kibuey went to study in Washington, D.C. The "change in regime and oppression of people" made it unsafe for her to return to Congo, she says, so she applied for asylum two years later in New Hampshire.

One of Kibuey's first jobs in the U.S. was at a Dunkin' Donuts, where she practiced speaking English. She moved to Vermont in 2006, shortly before completing a master's degree in community economic development at Southern New Hampshire University.* Today, Kibuey is a mother of two with family in both Vermont and Congo.

It took her a couple of years to find a job that involved both collaborative work and community development. "I pushed and pushed myself," Kibuey recalls.

The sci-fi and adventure-movie fan says her life experience helps her to connect with clients, some of whom are asylum seekers and don't qualify for most benefits. "If you never went through this [hardship], it's very difficult to comprehend. You can't," Kibuey explains. But she offers more than empathy. "You can be the definition of support and help because you've been through it. You know how hard it is," she reasons.

Kibuey believes her presence gives hope to clients who are former refugees or asylum seekers. Many arrived in the U.S. with a "survival mode" mentality, focused on finding jobs so they could provide for their families. "You can keep on working without even knowing that you can do better," Kibuey laments. She works to show these clients how to tap into resources that will help ensure that their children are not trapped in the same cycle.

"The fact that I'm here and could help them gives them the hope that, Yes, one day, I might be able to be in that position, or my children might be in that position, helping others," Kibuey says.

Preserving Culture

- Matthew Thorsen

- Aline Mukiza

According to another African saying, it takes a village to raise a child. Back in Burundi, if Aline Mukiza saw a child roaming the streets aimlessly, she'd tell him or her to go home. "I consider a child from my community mine," she says. The polyglot spent seven years as a multilingual liaison for the Burlington School District and will soon take up a new job as a family service coordinator at the Vermont Family Network.

Burundians began to arrive in the Green Mountain State less than a decade ago. Political instability and ethnic conflicts had forced most to spend years shuttling between refugee camps in the African Great Lakes region. Many were deprived of an education. But Mukiza, who's in her early thirties, had the opportunity to attend schools and earn a degree in Tanzania. "I was lucky," she says.

That good fortune instilled in her a sense of duty to serve her community and be a role model. "Getting a degree without helping others is not a good thing," Mukiza stresses.

Though she fled her native country more than 20 years ago, Mukiza uses her work in Vermont to promote the traditional Burundian value of collective responsibility for child rearing. In addition to her position at Vermont Family Network, she's the coordinator of the Heritage Learning Program, a project of the Burundian American Association of Vermont, which offers Kirundi and French language lessons, math tutoring, and social studies classes to children.

The BAA, launched in 2008, started the Heritage program in 2011 to address a problem: Burundian families had noticed their children were losing fluency in their native languages as they acquired English-language skills. The difficulty of communicating with their parents led to family conflicts, and the loss of Kirundi language put Burundian culture at risk of disappearing.

Nurturing Burundian identity and Christian values in children while they're young is the best way to ensure they preserve that heritage while integrating successfully into mainstream American society, Mukiza says. She quotes a saying: "Igiti kigororwa kikiri gito." (A tree is only straightened while it is still young.)

The program currently has four teachers, including Mukiza, and 25 Congolese and Burundian students who meet every Saturday at Burlington High School. Students who attend the program for at least three years will earn a half credit at Winooski or Burlington high schools, Mukiza says.

Over the years, the Heritage Learning Program has received various grants of $2,000 to $3,000, which it uses to buy Kirundi and French books from the Republic of Burundi, compensate students' transportation costs, and provide small stipends to teachers. Since 2015, members of the Refugee Outreach Club, a nonprofit started by Champlain Valley Union High School student Natalie Meyer, have been tutoring the students in math and organizing fundraisers.

As coordinator, Mukiza writes grants, transports students, picks up snacks, and liaises with teachers and volunteers. She also teaches traditional Burundian dance to girls and women. The troupe, Twibukanye, doesn't hold regular practice sessions, she says, but members get together whenever they receive invitations to perform.

About 30 Burundian families live in the Burlington area, Mukiza says. Though they are "here to stay," they haven't forgotten friends and family in their African homeland, especially children who have lost their parents to the country's AIDS epidemic. One day, the BAA hopes to send school uniforms to Burundi and support the education of the nation's orphans, Mukiza says. She adds, "Children feel comforted knowing other people care for them."

Fighting Injustice

- Matthew Thorsen

- Isra Kassim

Isra Kassim's email signature includes a quote from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.: "Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere." The 24-year-old Somali Bantu, a member of the local chapter of Black Lives Matter, names the leader of the 1960s civil rights movement as her inspiration.

Kassim is a rarity among Somali Bantu women in that she's involved in community activism.

"Some people, especially the refugees, don't want to be involved in this kind of thing. Some feel that American people are the ones who brought them here and they shouldn't be ungrateful," Kassim says of Black Lives Matter. But she thinks differently: "We were told this is a free country and it's the land of opportunities. We're not getting those opportunities, and we have to fight."

During the day, Kassim works as a program specialist for the Association of Africans Living in Vermont. Her duties include helping clients apply for citizenship and running outreach programs. But her main passion is pushing for equal education rights for black children. Recently, she participated in a march in St. Albans to decry racism in the schools.

"People think we're trying to cause problems. But we're not. What's wrong with standing up for your rights?" Kassim asks. "If you don't have the education that you need, then you can't meet the needs that you want for your family, or whatever it is that you want for your life."

Kassim arrived in the U.S. from Kakuma Refugee Camp in Kenya in October 2006. As a freshman, she enrolled in the English Language Learner program at Burlington High School. At the end of her sophomore year, she had to argue her way out of the program to take regular classes. "I didn't want to get stuck in ELL classes. I wanted to go to college. And you can't go to college with elementary math," says Kassim. She graduated from Champlain College last year with a degree in business administration.

Kassim recalls experiencing personal mistreatment at school and overhearing the staff make disparaging remarks about her refugee community. Though some told her she was "different," that gave her little comfort, she says. "If you're talking about Somali Bantu, you're talking about me, 'cause I'm part of them," she remembers telling a teacher. "It's not fair of you to be putting them down."

Her desire to help her family — and, by extension, her community — is a major motivation for Kassim. "A lot of kids are graduating from Chittenden County schools not knowing how to read, and it's very, very upsetting," she says. "These kids don't know how to advocate for themselves, and their parents don't want to get involved because they're afraid they're going to be targeted, things are going to happen."

The political persecution that Bantus experienced in Somalia contributes to this fear. But Kassim has no qualms about standing at the forefront of civil rights activism. She wants to "finish the job that Martin Luther King Jr. and others started."

Ensuring that no child is left behind isn't Kassim's only passion. She's also involved in groups that seek to address health disparities among Vermonters and youth incarceration. "We can't all sit here and say, 'Who wants to lead?'" Kassim says. "Even if it's a little change, it's still something."

*Correction March 9, 2016: An earlier version of this story misreported the order in which Kibuey moved to Vermont and completed her master's degree. In fact, she moved just before she finished her degree.

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.