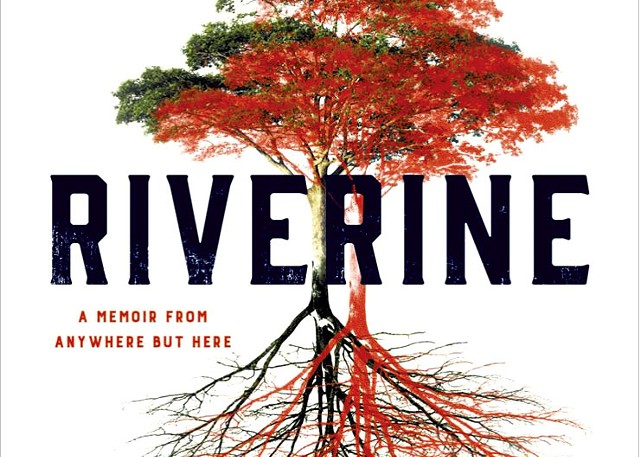

Burlington writer Angela Palm's Riverine: A Memoir From Anywhere But Here won the influential annual Nonfiction Prize from her publisher, Graywolf Press. It arrives this month garlanded with advance praise, including starred reviews in Publishers Weekly and Kirkus Reviews and a Best Book commendation from Apple iBooks. A professional editor and writing coach, Palm is the founder of Ink + Lead Literary Services in Burlington, and she's taught creative writing at Champlain College and the New England Young Writers' Conference.

Readers love memoirs, which offer not only the sensation of walking in someone else's shoes but sometimes even that of slipping into another person's very thoughts. The essential ingredients of a memoir are engrossing life circumstances and a narrative voice that sounds convincingly immediate. We experience a memoir's storytelling as we do that of a first-person speaker in a novel, but we're invited never to forget that the events recounted truly happened.

The narrative elements of Riverine are compelling. Palm was born and grew up in a rural Indiana farming community where a river had been forcibly rerouted. From time to time, the water would reclaim its ancient bed, flooding the countryside and destroying any pretense of permanence. When Palm was a teenager, her best friend was Corey, a next-door boy whose family perils and troubles at school led to more and more egregious misbehaviors. They culminated in the stabbing murders of two elderly neighbors and a life sentence in prison without parole.

- Riverine: A Memoir From Anywhere But Here by Angela Palm, Graywolf Press, 272 pages. $16.

After college and various events, Palm's narrator marries and becomes a parent; then she and her husband decide that they need to "reboot" their lives by moving to Vermont. From her new home, Palm reaches out to the incarcerated Corey, to whom she's been writing unsent letters for years. (She shares none of these with the reader.) Eventually, Palm returns to Indiana to visit him in prison. The impact of their first encounter as adults affirms the childhood friends' ineffaceable connection. That visit also results in their mutual acceptance that they will live their lives separately as a consequence of unpardonable Corey's crimes.

Some memoirs, such as Mary Karr's powerful The Liars' Club, shift their perspective to show a narrator responding from different vantage points in maturity to events that are sequenced dramatically but not necessarily "chronologically." By contrast, Palm's narrative moves step by step from childhood. Riverine also differs from memoirs that aim to convey the volatile perceptions of a younger person (as Frank McCourt did in Angela's Ashes): Palm's chronicler is positioned throughout as a present-day adult, looking back with running commentary.

Essayistic prose is such a flexible vehicle, able to turn rapidly or float steadily — like a magic carpet. Yet, while there's enchantment in reverie, the magical conveyance also needs to be aerodynamically sound, and too often Palm's narration seems drafty, too loosely fashioned and aimed. Since her chapters don't really stand as self-contained essays, the story's year-by-year progression can meander and stall in places, its pacing settling into, "Then this happened, then this, and then this." And, because Palm has a penchant for summarizing events and relationships instead of dramatizing them, some stretches of the book read like ruminations scribbled in a journal, such as this one:

I didn't hear from Corey for a few months after that visit at the new house. He could have called, but didn't, and he had no phone at the new place he was staying. By then he'd been in enough trouble that dating him would have been out of the question — my parents wouldn't have allowed it. When it became clear that nothing would happen with Corey, I dated the first boy I came across. I'd been hanging out with a girl named Kelly, and Trevor was her boyfriend's best friend. It was a convenience match. He was cute and nice, so sure. Fine by me. I would project all that Corey love onto him.

In some places, Palm uses conceptual devices to strengthen her narrative structure. A chapter titled "Dispatches From Anywhere But Here," echoing the book's subtitle, is scaffolded on the names of criminal-justice theories that Palm studied in college: "Broken Windows Theory," "Routine Activities Theory," "Biological Theory of Deviance" and so on. But the chapter suffers from repeated references to people who aren't introduced or vividly developed. We gain little understanding of how this young woman discovered (and invented) herself during the years that followed those unexplained murders committed by Corey, who remains a cipher though his name appears here and there in the chapter.

The most powerful sections of the book involve Palm's visits to the Indiana prison — first with her mother to see an uncle who's been locked up for attempted murder, then later to see Corey for the first time in 16 years. In these more fully dramatized scenes, Palm uses quoted dialogue and intently observed details to bring her reader into the room and into the enormity of feelings at stake.

The account of that climactic visit to Corey in prison pivots on a set of rules, stated without arty fanfare, that propel the personal narrative forward:

1. On a contact visit in prison, you may briefly embrace when the inmate enters the room.

2. On a contact visit in prison, you may bring up to twenty dollars in quarters in a clear plastic bag. The inmate may not touch the quarters.

3. On a contact visit in prison, you may not wear any jewelry.

In this chapter, Palm is finally able to communicate the tremendous and lasting power of time spent with a childhood intimate, while being specific and informative about the conditions of prison life. By holding her focus closely on the story, which here unfolds in a conversation under surveillance by guards, she allows us to see and feel much more than she could with a disjointed, years-later summary. As the two friends recall how, as teenagers, they would watch each other's adjacent houses at night, a reader can apprehend what's been lost, never to be recovered.

"We would have met in the middle," I told Corey. "Half-bad, half-good. Half-reckless, half-restrained. Maybe we would have saved each other."

He started to cry at that, but I watched him silently talk himself down from it. "You know, I used to watch you, too," he told me. "From my window."

"No way," I said. "Really?"

"I did. Your room was always such a mess. I used to watch you brushing your hair or reading your books."

"That's all?" I asked, remembering how I'd dressed in front of the window each night after my shower.

He laughed and blushed. "No, that's not all. My mom caught me once."

"So we were doing the same thing. And it wasn't just me."

Every memoir is idiosyncratic, reflecting an author's particular perceptions and manner of relating to the ingredients of a life over time. Palm is enamored of analogies for Riverine's form, and she proffers several, calling her structure "digressive" and "segmented" and comparing the book to a "patch-quilt" and "collage." Yet her most moving and reverberating passages resist this habit of veering into digressions that summarize or philosophize.

Unlike an autobiography, a memoir has no obligation to be comprehensive and lifelong. Yet page after page of Riverine seems to miss opportunities, wandering across the years and rarely focusing on what happened to Corey, or the impact of his crimes and incarceration on the narrator. The book would be more penetrating if its storytelling strategy had been more selective, concentrating on the question of how one childhood friend ended up imprisoned for life while the other wonders what might have been.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.