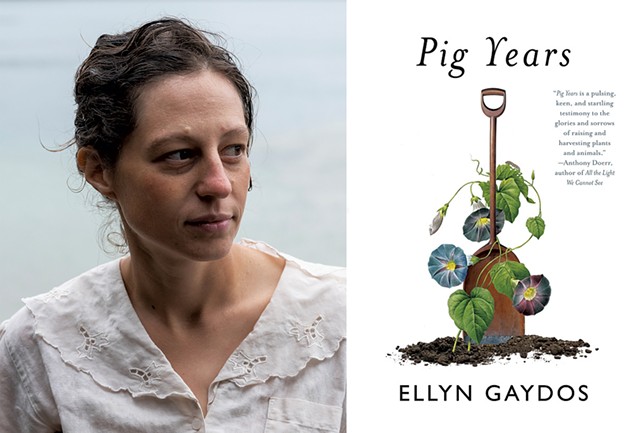

- portrait courtesy 0f Shane Lavalette

- Ellyn Gaydos |

Pig Years, by Ellyn Gaydos, Knopf, 212 pages. $27.

Vegetarians and skeptics of the cloven-hoofed, beware: Ellyn Gaydos' stellar debut memoir, Pig Years, might have you salivating.

Lovers of sumptuous prose, rejoice. Pig Years delivers an intimate look inside the world of young, semi-itinerant farmers in Vermont and upstate New York. Or rather, worlds — because that group, composed of neither children of hardscrabble farm families nor immigrant laborers, is too diverse to be summed up neatly as a subculture. Gaydos and her comrades farm because of their love for meaningful, elemental work and the relative freedom it allows — and because of their unease with society and uncertainty about the future, which simmer just below the surface.

Early in the book, Gaydos sees a "Help Wanted" sign and realizes she could earn more money in the Price Chopper deli than as a farmhand. She swiftly dismisses the possibility, preferring to remain "as answerable to weather or bugs" as to a boss. She acknowledges hers as a privileged choice, writing with a keen (and downright refreshing) awareness of class.

Neither a journalist parachuting into the barnyard nor an upper-cruster cosplaying as a noble peasant, Gaydos was born and raised in Vermont and started working on a beef and vegetable farm at age 18. Since then, in addition to farming, she's won the Richard J. Margolis Award for writers of social justice journalism and graduated from the Columbia University MFA Writing Program.

Gaydos' lush descriptions tend toward rhapsody, and her language is fresh, torqued throughout with poetic turns of phrase. After long hours of sausage making, she writes:

My fingers, soft with fat, smell faintly of iron and the crisp oil of lovage and bitter parsley, the diesel of thyme and oregano, so sensual that I unabashedly pass the softened and perfumed palms of my hands over my nose and cheeks, sniffing politely as one who does not deserve that which I am given and that which I have taken away.

Her tone can turn blunt, though, when detailing the inherent violence of farming. "Once, I slaughtered some unwanted rooster for a farmer and didn't realize till hours later my face was splattered in dried blood," she writes.

The book began as notes the author jotted down while working, and it brims with devotion. Gaydos' eye drinks deep of everything she encounters, filling with earnestness, love and wonder. Into the narrative she weaves threads of her personal life, obscure bits of pig wisdom (such as an equation for calculating a pig's weight without a scale), and a constant awareness of how the cyclical realities of nature, its "attendant bloom and rot," extend beyond a farm's property line.

The result is a memoir that sizzles with immediacy, composed mostly in present tense and structured chronologically as a journal. The chapter titles announce seasonal shifts and the author's moves from farm to farm. She follows a combination of instinct and financial necessity, traveling mostly among farms in Barre, Vt., and New Lebanon, N.Y. The grit and struggle of both of those towns, with their peeling Victorian houses and off-track gambling bars, contrast vividly with the sumptuous fertility of springtime planting, the dizzying bounty of fall and the urgency of preparing for winter.

The book's main personal strands are established early on. Gaydos describes the thrill of falling for Graham, her somewhat less earthy but loving partner, while making it clear that farming will always come first for her. "How could you trade the sky, the water, or the mountains for a single heart?" she asks herself. As the book unfolds, however, the author's nurturing spirit (not to mention all the animal husbandry going on) sparks a growing desire for motherhood.

A revolving cast of farmhands populates Gaydos' world and occasionally blends together, never fully entering into the narrative. The book tracks the author's deepening romance with Graham, who comes in and out of her farming life, but as a character he remains fairly opaque, absent or at the fringes of the story. Family members also make appearances and provide a window into the author's upbringing, though that window never opens particularly wide.

Perhaps these limits are for the best. The real engine of the book is the author's own mind: restless, observant and almost extrasensorially empathic. The creatures she nurtures and befriends she also renders, both on the page and with a very sharp knife. A sacred, funereal air haunts the slaughtering scenes, especially when they follow a description of Gaydos baking the pigs' cakes for their last meal, which she serves to them with a 40-ounce of malt liquor.

The chapter called "Luke" introduces the book's most complex character: a fellow farmhand who's always down on his luck. We are given to understand that Luke, a struggling yet tender soul, is addicted to alcohol and pain medication and conflicted about his gender. He was recently fired for stealing money from the farm's coffers.

This portrait generates a juicy tension, which Gaydos cuts short by folding Luke's character into the book's elemental ruminations on abundance and loss, crops ruined by insects and the slaughter of beloved pigs. There's an inherent lack of sentimentality in Mother Nature, with whom Gaydos is becoming more and more intimately acquainted — but Luke's fate rattles her in a different way.

The rhapsodic descriptions of nature's vitality in the first section give way to profound meditations on loss and destruction as the book continues. Gaydos finds intriguing and original entry points for her musings: nursing pigs through illness, watching Gov. Phil Scott race at Thunder Road in Barre, reading journal entries of the doomed Shaker community on whose former property she's farming. Ultimately, she herself experiences nature's brutal impassivity in wrenching, personal ways.

The prose in Pig Years crackles all the way through. At once an insider's look at the scrappy world of small farming and the story of a young writer's restless devotion and grief, Gaydos' debut announces her as a major new voice in nonfiction. You might find yourself devouring the book in one sitting, as this reviewer did. Just don't try it on an empty stomach.

From Pig Years

In the heart of the summer, Diana, Lee, Sam, Bet, Chris, and I are dwarfed by the farm, the sheer life force of it, pulled by the demands of plants and animals, pressed like blunt objects into the ground, buried in the work we have wrought. A dairy farmer told me cows — meaning milking cows twice a day every day — can either turn a person mean or make them nice. I believe this is true. You either like a cow's touch, are quick to recognize the good in their temperament, or you dock their tails for swatting your face like a fly, hate the smell of your own sweat, as if it were their manure. With vegetables, perhaps either you go into the earth and are softened by it, or you come out like thistle. It is labor that is either heart opening or hateful, but sometimes unavoidably both.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.