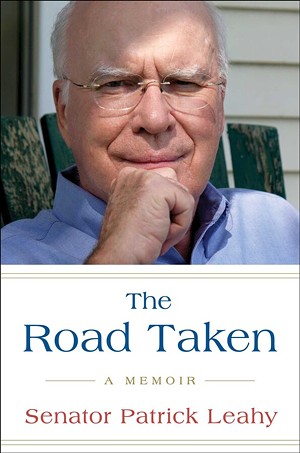

- Courtesy of Simon & Schuster

It’s an incredible ride, with stops at some of the most important events in American politics of the late 20th and early 21st centuries — from the first Senate race that Leahy won as one of several “Watergate baby” Democrats elected the year after Richard Nixon resigned the presidency to the insurrection of January 6, 2021, when Donald Trump’s supporters stormed the Capitol to “Stop the Steal” and tried to prevent Joe Biden from assuming the presidency.

Leahy doesn’t hold back in his criticisms of some of his Republican Senate colleagues, including Mitch McConnell, Ted Cruz, Lindsey Graham and Rand Paul. He also bemoans the loss of civility, honor and collegiality in an institution he clearly reveres and always has, from the wide-eyed, pinch-me days when he served as the wet-behind-the-ears bartender for his colleagues in majority leader Mike Mansfield’s backroom chamber to his final years as the body’s longest-serving current member and Senate president pro tempore, third in line for the presidency.

The highlight reel is extensive. We read about Leahy’s 1975 vote to end the funding for the Vietnam War, his dogged efforts to ban land mines as weapons of war, and the threat on his life from an anthrax attack. We get an inside view of some of the 18 U.S. Supreme Court confirmation hearings during his tenure, several of which Leahy oversaw as chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee; of his work as chair of the powerful Senate Appropriations Committee; and of the nine U.S presidents with whom he interacted during his six decades in Washington, D.C. He also tosses in his childhood memories of riding his tricycle through the Vermont Statehouse.

Leahy’s well-known healthy ego and occasional chest thumping don’t detract from the charming stories he tells. And his love and appreciation for his wife, Marcelle, to whom he gives half the credit for his political success, shine through in the 448-page tome. She embodies the overused description of a spouse as “my better half,” and at the end of the book, you want to hug her as much as you want to shake the senator’s hand for a job well done.

Marcelle is clearly Leahy’s rock and conscience; when he describes his service in the Senate as a “partnership,” it’s not trite but true. As he notes, her counsel was so important and their bond so strong that Marcelle — a registered nurse who supported the couple by working with veterans while Patrick attended Georgetown Law School — could have easily been listed as the memoir’s co-author.

The book is not without faults. Leahy makes no mention of his unauthorized release of a Senate Intelligence Committee report during the Ronald Reagan-era Iran-Contra scandal, a move that earned him the nickname “Leaky Leahy” from detractors and the media. The omission is unfortunate. The incident could have been an opportunity for Leahy to demonstrate self-reflection on a black mark in an otherwise scandal-free political career.

There is zero discussion of Leahy’s huge role in the decision to base F-35 fighter jets in Vermont, a decision that would bring roaring engines to Burlington and generate significant opposition and controversy. Leahy also doesn’t bring up the betrayal he felt when Vermont developers, including his friend Bill Stenger, abused the EB-5 investor program that Leahy had championed (and later helped reform).

Leahy also comes across as overly dismissive when he goes on for pages about his first reelection campaign in 1980, a nail-biter he won by some 2,400 votes, and only identifies his opponent, Republican Stewart Ledbetter, near the conclusion. In addition, he doesn’t even bother to name the opponents he drubbed in his last two landslide reelections.

Leahy is quick to admit that the Senate lacked diversity when he arrived in 1975: It was all male with only one Black member, Edward Brooke of Massachusetts. He notes that the 1992 election of several women provided a welcome breath of fresh air. But his pining for the spirit of his early days — more collegial, less partisan, with deals sometimes brokered behind closed doors — might strike some readers as too nostalgic, clubby and out of step with today’s more woke world.

Leahy doesn’t amplify his reasons for stepping aside, other than making passing references to wanting to see a new generation take over; to witnessing the increased dysfunction of the world’s greatest deliberative chamber; and to wanting to go out on top, unlike predecessors who hung on too long, such as Strom Thurmond. He makes no mention of Marcelle’s 2019 leukemia diagnosis, leaving us to wonder whether and to what extent her illness might have played a role in his decision not to seek another term.

But Leahy’s omissions, slights and choice not to discuss personal health matters are outweighed by the wonderful stories he tells in The Road Taken. We hear about being trapped in a stuck elevator with Supreme Court nominee Sandra Day O’Connor; about his warm friendship and inside jokes with president Barack Obama; about his love for Teddy Kennedy and mentor Hubert Humphrey; and about his relationship with Sen. Bernie Sanders and his decisions whether to endorse the latter’s 2016 and 2020 presidential runs.

Leahy also speaks eloquently of the palpable relief he felt when visiting the family farm in Middlesex, of spending time with his three children and grandchildren, and of having been born blind in one eye.

Of his relationship with Obama, he writes:

The following week, we were back together again in the gym.

“Pat, I noticed something. Your wife calls you Patrick.”

“Yes, she does,” I said, curious as to where this was going.

“Michelle calls you Patrick too, because she got that from Marcelle.”

“Okay.”

“What do you prefer?”

“Well, in my family, people who know me best do call me Patrick.”

“Not Pat.”

“As an elected official, Barack, people could call me a lot worse than Pat, but yes, my friends call me Patrick.”

“Well, Patrick — we still need to get rid of those ugly sneakers.”

It was Barack and Patrick from that day forward. But I wasn’t relenting on the footwear.

The Road Taken is a who’s who of American politicians of the last half century, with Leahy at the center of so many key historical events that only Forrest Gump could rival him. His descriptions of McConnell and Trump alone are worth the $30 list price.

Invoking the state’s first poet laureate, Robert Frost, is a bold move for any Vermont writer. But Leahy’s political career is so chock full of achievements that Frost could only have been proud the senator used a play on one of his most famous poems for the title of his memoir.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.