- Matthew Thorsen

- A Hindu gathering last week

On Sunday mornings at the Burlington Friends Meeting House, a small gathering of Vermont Quakers communes in silence with God. This has been a familiar scene in New England for a few hundred years. The congregation that worships in the adjacent Bassett House on North Prospect Street is much livelier.

Since mid-July, the Vermont Hindu Temple — an organization seeking to build its own gathering place — has been holding services as part of weekly meetings in the historic home that once belonged to Mary Martha Fletcher, namesake of Burlington's library and, until recently, its hospital.

At the beginning of the group's first meeting in July, a Hindu priest set up a small altar on a fireplace mantle. Beneath a framed print of animals filing into Noah's ark, he placed a small painting of the four-armed Hindu god Vishnu, a miniature statue of the elephant god Ganesha, candles, a coconut husk and two vases of flowers. Two helpers handed out more flowers to the group of nearly four dozen worshippers. Most of them were Bhutanese men in their fifties and sixties who came to the United States in recent years from refugee camps in Nepal. Many wore long cream or beige tunics and Dhaka topis, traditional Nepali hats.

The priest then led the group in worship in Nepali. They prayed for peace and health and honored their ancestors. At the end of the ritual, the devotees placed their flowers at the altar.

The somber mood gave way to joy as the group began its kirtan session — meditative singing of devotional hymns. They clapped their hands as they chanted the names of Hindu gods and goddesses, sang about them and praised their qualities. They sang:

Gopala Gopala, Devakinandana Gopala. Devakinandana Gopala. Devakinandana Gopala.

Translated from Sanskrit, it means: "Baby Krishna, baby Krishna, is the joy of his mother."

Guitar, harmonium and flute players accompanied the rising and falling voices, along with a percussionist on the tabla, a traditional hand drum. The tabla player's face glistened with sweat as he matched the tempo of the chanting.

Although most of these Hindus have a private altar at home, they still wanted to come together to pray. In Vermont, that's not always possible. The nearest Hindu temple is in Albany, N.Y., and only a fraction of the area's current Hindu worshippers can fit in their new weekly meeting spot at the Bassett House.

In an interview before the initial, mid-July service, Basu Dhakal, a member of the Vermont Hindu Temple's interim executive committee, explained that for the first meeting, they invited 30 pandits, or priests. These were the people who would ultimately run the temple. Others had wanted to attend that gathering — and they may be able to attend future meetings — but the space is limited.

"We couldn't even invite our own mothers," Dhakal said.

Dhakal is an enthusiastic 33-year-old nursing student who lives in Burlington. A Bhutanese Hindu, he came to Vermont in 2012 and is active in the newly organized effort to establish a temple in the area, a place where the community's elderly can socialize and carry out religious practices at any time of the day, and where the younger generation can learn the Nepali language and customs.

The Bhutanese aren't alone in wanting to find a place that can be used to fulfill their religious, cultural and educational needs. Tibetans in Vermont are seeking to build their own community center, too.

Both groups arrived in the Green Mountain State from the Himalayan region of southern Asia, though at different times and for different reasons. They've established businesses and restaurants — Seven Days food writers reviewed five of them last week — and have woven themselves into the fabric of the community, especially in the Burlington area. Now they're seeking to build spaces of their own.

Raising the Temple

- Kymelya Sari

- The Vermont Hindu Temple in Bassett

Bhutanese refugees began arriving in Vermont in the last decade. Most of them are descendants of ethnic Nepalis who settled in Bhutan in the 19th century to cultivate the land. They developed the area and prospered, with some becoming high-ranking government officials. The Citizenship Act of 1958 granted them citizenship rights.

But in 1989, King Jigme Singye Wangchuck implemented the "One Nation, One People" policy, as fear of the burgeoning Nepali community grew. He imposed the culture and religion of the local majority, the Buddhist Drukpas, on the Nepali settlers. Tens of thousands of ethnic Nepalis were stripped of their Bhutanese nationality and expelled from Bhutan, and an entire generation was born and raised in refugee camps in Nepal and India.

The refugee crisis lasted 16 years before, in 2006, the U.S. offered to resettle the refugees; other countries including Canada and Australia subsequently followed suit. Between 2008 and 2013, Bhutanese refugees were one of the three largest groups to be resettled in the U.S. To date, the U.S. Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration said about 80,000 Bhutanese refugees have been admitted to the country.

The Vermont Refugee Resettlement Program puts the local number at 1,653.* But because refugees often relocate to be closer to family members, the temple group estimates there are about 2,200 Bhutanese in the state.

And that's expected to grow — VRRP is anticipating resettling additional Bhutanese refugees in Vermont, in particular those whose family members are already here.

Some of these new arrivals are Buddhist and Christian, but most are Hindu. For these Hindus, their daily life, culture and religion are intrinsically linked — just like "nail and flesh," said Bidur Dahal, another member of the Hindu temple's executive team. Dahal, 40, arrived in Vermont in 2012 and lives in Colchester. He works as a medical case manager and interpreter at VRRP. "If there is no temple in the community, the life of the people will be difficult and spiritually hollow," he said.

The temple will fulfill multiple needs — spiritual, social and cultural — in ways that nonprofit groups can't, Dahal said. The temple will be particularly important to the elderly Bhutanese, who tend to spend most of their time indoors and feel isolated, especially during Vermont's long winter months.

Even so, Dhakal emphasized that the temple isn't just for the Bhutanese. Although the refugee community is spearheading the creation of the Vermont Hindu Temple, the executive team welcomes all Hindus and anyone who's interested in Hinduism.

He pointed out that the Bhutanese organizers invited members of local kirtan groups to participate in the temple's inaugural service. One of them, Jeffrey Reicker, gushed about leading the group while being accompanied on guitar. He said the experience was "wonderful."

State Rep. Kesha Ram (D-Burlington), who works as a public engagement specialist for Burlington's Community and Economic Development Office, is also Hindu. In her spare time, she serves as a volunteer adviser for the temple. Ram, who attended multiple temples while growing up in Los Angeles, came to Burlington in 2004 to study at the University of Vermont. She said it is important for the Bhutanese to have their own space.

"For many Hindus, particularly for those who are new to the U.S, it's difficult to separate their cultural and social needs from their religious and spiritual ones," Ram said. "The temple is also a civic gathering place for people."

Building a temple will require serious fundraising. Ram expects it will take five to 10 years.

Constructing a Center

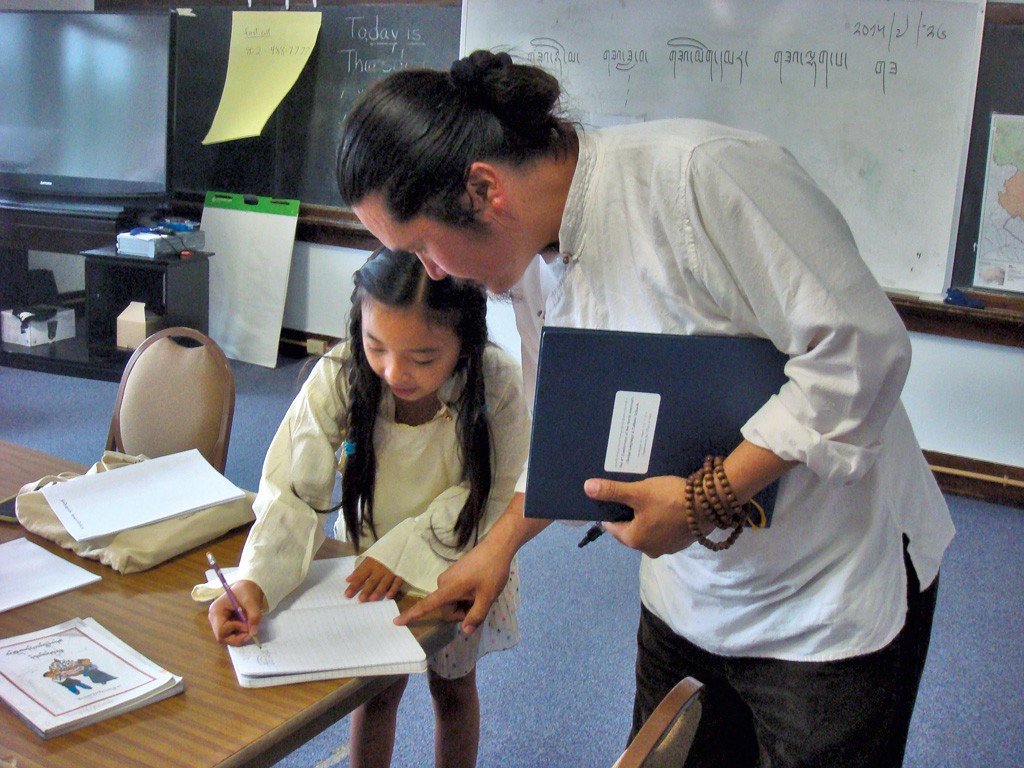

- Kymelya Sari

- Tseten Anak with a student

Compared with the Bhutanese community, Vermont's Tibetan group is smaller — albeit more established. Many Tibetans have been in the state for two decades.

A crackdown by the Chinese government against a Tibetan uprising in 1959 forced thousands into exile, including the Dalai Lama, the spiritual leader of six million Tibetans. Under the Immigration Act of 1990 and through a Tibetan lottery, 1,000 Tibetan exiles in Nepal, India and Bhutan received U.S. visas. Twenty-six of them immigrated to Burlington in 1993.

However, unlike other immigrants who arrived in Vermont as refugees, the Tibetans were classified as "displaced people" and did not receive financial assistance from the U.S government. Rather, Burlington's nonprofit Tibetan Resettlement Project was created in 1992 to help them get established. The community now consists of about 160 individuals — close to 40 families.

The Tibetan Resettlement Project is now defunct. Its former director, Jim Kelley, a science teacher at Edmunds Middle School, is cochair of the Tibetan Association of Vermont committee tasked with establishing a community center.

Although the Tibetans have used the Burlington Shambhala Center and the Vajra Dakini Nunnery in Lincoln, they still want a space of their own.

A gathering space will give the Tibetans "a sense of permanence," said Kelley, whose wife, Yangchen, is Tibetan. "People have to have a place to do things together to keep [them] alive."

With the help of a local architect, Kelley's committee now has a blueprint for a proposed facility. It also has a three-phase plan and is looking to buy a plot of land. With that, it could begin constructing outbuildings, such as a pavilion, and a main structure with a classroom, prayer hall and shrine. The space will be modeled on those found in India, where the community can gather to pray, have tea, catch up on news, and dance and sing traditional songs.

"We feel good about our plan," Kelley said, adding that he expects the committee's efforts to take between 10 and 15 years to come to fruition.

Even before the Tibetans rallied around the idea of building a community center, they were already working toward preserving their culture. In January 2011, the Tibetan Association of Vermont started a weekend school so that the younger generation could learn Tibetan language and traditions. Today, the school has 12 pupils in pre-K and second grade. Wearing variations of the traditional Tibetan dress, mostly brought from India, the students meet every Sunday at the Association for Africans Living in Vermont, at 20 Allen Street next to St. Joseph's Co-Cathedral.

In late July, during their last class before the summer break, the children started their morning by singing the Tibetan national anthem. Sitting upright, with their palms facing each other and resting against their chests, they then chanted Buddhist mantras and prayed for the Dalai Lama's health. A teacher intermittently called out students' names, and they would immediately straighten their backs and bring their slackening hands closer. Most of the girls wore ankle-length robes bound at the waist by a sash, while the boys wore bell-sleeved shirts to go with their less-than-traditional athletic shorts.

The pre-K pupils traced letters of the Tibetan alphabet, while those in second grade practiced writing the days of the week. The students conversed with one another in English, though they mostly spoke in Tibetan with their instructor, Tseten Anak. Born and raised in a Tibetan settlement near Mysore in southern India, he now lives in South Burlington and works as a nursing assistant. Anak is vice president of the Tibetan Association of Vermont. "At school," he said, speaking in his measured voice, "it's a reminder of where they came from."

Merging Multiple Identities

- Kymelya Sari

- The students in the Tibetan Association of Vermont's weekend school

While the Tibetan and Bhutanese groups are keen to preserve their cultures, they are not trying to remain distinct and separate from American society.

Although cultural preservation may be "seen as a sign of separation," that's "not really the case," said Noriko Matsumoto, an immigration scholar in the sociology department at the University of Vermont. Matsumoto explained that current scholarship views preservation of one's native culture and assimilation into a new society as being consistent with each other. "The maintenance of ethnicity is compatible with being American," he said.

Tenzin Lhakhang, secretary of the Tibetan Association of Vermont, credits the U.S. for "helping us when we couldn't stand on our own." But, he said, "We need to remember we are Tibetans."

Using the Jewish population and its cultural centers as an example, Lhakhang said it's possible for any individual to have multiple identities. A person can be Jewish and American. Kesha Ram is Hindu and Jewish; she calls herself a "HinJew." In the same way, a person can be Tibetan or Buddhist and American.

The older Tibetans came to the U.S with their customs and want to pass them on to their children. They're aware they need to learn the ways of their new country, too.

Both the Tibetan and Bhutanese groups said that the new spaces they envision will serve as hubs of cultural exchange — other communities would be welcome to use them. That's the long-term vision. For now, they know a huge task lies ahead: achieving financial solvency. Both communities plan to hold fundraising events and seek private donations to bolster those from their own members.

Although assuming the burden of a mortgage is a "scary undertaking," according to Kelley, the Tibetans said the project is worthwhile because the community center would be theirs.

Dahal, speaking for the Bhutanese executive team, said the temple would mark an end to what he describes as the Bhutanese refugees' "spiritual homelessness."

There is clearly a demand within the community. Although the Hindu Temple group restricted attendance at its inaugural service, a few extra congregants tagged along. Eighty-three-year-old Ganga Maya Dahal was one of them. Through a translator, she said she enjoyed the gathering. "We had many people," she said. "We were together and it felt nice."

Correction 12/14/15: An earlier version of this story misstated the name of the Vermont Refugee Resettlement Program.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.