- Yogeswari Khadka

About 60 people gathered at the Elmwood Meunier Funeral Home in Burlington's Old North End on October 18 to mourn the violent death of Yogeswari Khadka, a 32-year-old woman who was killed a week earlier just a few blocks away. Bhutanese business owners, an elementary school teacher, mental health professionals and staffers from organizations that provide services to refugees were among those who attended the wake, where Khadka's open casket was on display in the Hindu tradition. Some wore purple ribbons in support of domestic violence awareness.

Khadka's husband, Aita Gurung, allegedly hacked her to death with a meat cleaver. He used the same weapon to seriously injure his mother-in-law, Tulasa Rimal, 54.

Chandra Sharma, secretary of the Green Mountain Bhutanese Organization, read Khadka's obituary aloud in Nepali: name, date of birth, date of death, where she lived, the names of family members. Basu Dhakal, president of the Bhutanese-led Vermont Hindu Temple, translated the just-the-facts account into English for the benefit of non-Nepali speakers.

Later, a convoy of vehicles accompanied Khadka's body to a crematorium in South Burlington, where a Buddhist monk conducted funeral rites in an adjoining function room. Gurung's family is Buddhist; Khadka's family is Hindu. Bhutanese of all faiths, including Christians and Kiratis, were represented.

So was the Burlington Police Department. Dedicated domestic violence investigator Nikki Moyer attended the service.

"Everybody is shocked," Dhakal told Seven Days a few hours before the funeral. "Not only the Bhutanese living in Vermont, but everybody in the United States."

A confluence of factors — alcohol abuse, mental illness, problems adjusting to a new culture and environment — may have contributed to the attack. But trying to understand what made Gurung snap is complicated because many Bhutanese people don't talk openly about their personal problems. Even Khadka's father, who lived with the couple, couldn't say for sure if the husband and wife were having marital difficulties.

Gurung's younger brother, Suk, has a bit more insight. On the last day of September, he visited Gurung at his Burlington home during Dashain, a religious festival that the Nepali Bhutanese community celebrates. But the joyous occasion took a dark turn when Gurung told his brother that he was ill and didn't have long to live, according to Suk.

Alarmed, Suk suggested to his now-deceased sister-in-law that she check Gurung into a "mental rehab." But Khadka reassured Suk that her husband was taking medication.

"He doesn't like to take medication, but I'm forcing him," Khadka said, according to Suk.

Two weeks later, on October 12, Gurung allegedly killed his wife in broad daylight. The brutal, bloody attack spilled outside the family's Hyde Street home, where neighbors and passersby tried to intervene before police arrived and arrested the 34-year-old suspect. Gurung has been charged with first-degree murder and first-degree attempted murder and is in custody, awaiting mental competency and sanity evaluations.

"I never thought that was going to happen," Suk told Seven Days through an interpreter. He said he learned of the crime from Gurung's father-in-law, Khadka Rimal, who is now caring for his 8-year-old granddaughter. She was at an after-school program when her mother was slain.

Suk said his brother's mental health issues predated the incident. He said Gurung tried to hang himself in 2015, a few months after arriving in the U.S. with his wife and daughter. Gurung also once confided that he felt anxious and heard voices, even when no one was around. But, eventually, Gurung stopped sharing his feelings with his brother and became withdrawn.

"I know he has a mental problem," Suk said.

- Kymelya Sari

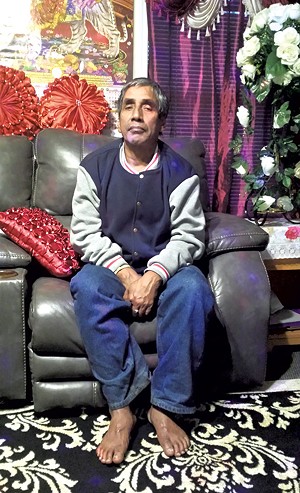

- Khadka Rimal

Gurung's personal struggle was likely exacerbated by cultural issues. "I personally have been involved with other families in the Bhutanese community to talk about mental health and domestic violence," said Dhakal, a registered nurse at the University of Vermont Medical Center.

"Our mothers and sisters have been affected by it, and they don't speak up," he said.

Traditionally, Bhutanese families don't seek help for domestic problems because they're concerned about family honor and prestige, explained Bidur Dahal, secretary of the Vermont Hindu Temple. "They don't go outside and seek help unless it's critical," he added. Going to the police, he continued, would be a last resort.

There is a reason for the mistrust of police among the Bhutanese community, Dahal explained. In the early 1990s, the Bhutanese king expelled about 100,000 Bhutanese citizens of ethnic-Nepali origin, also known as Lhotsampa, from the country. The army and police committed atrocities against the Nepali population, which included torture, killing and rape, according to Dahal.

The Lhotsampa fled to Nepal, where they lived in squalid and overcrowded refugee camps for about two decades. There, the Nepali police "were not friendly with the people," said Dahal. "They never spoke nicely. They were always arrogant."

Khadka and Gurung — and her parents, Khadka and Tulasa Rimal — lived in close proximity in one such Nepali camp. But they were separated two years ago, when the younger couple came to Vermont as part of U.S. refugee resettlement efforts. The Rimals arrived in January 2017. Two months later, they moved in with their daughter, son-in-law and granddaughter.

Khadka and Gurung used to get into physical fights when they were in Nepal, according to Khadka Rimal, 59. He never saw that happen in Vermont but said the young couple quarreled.

"We don't know what was happening in their room," Rimal said through an interpreter. "Sometimes, it seemed like they were having a physical fight. But they never told us what was going on."

Rimal did say Gurung had become a "regular drinker" in the U.S.

"He always wanted beer," Rimal said of Gurung. "If the beer was not at home, he would constantly bother Khadka."

According to Rimal, Gurung's cleaver attack on Khadka happened after she refused to "bring beer." Rimal's wife was injured as she tried to shield their daughter.

Rimal also explained that several days before the attack, Gurung had wanted to go to work with Khadka, though the older man did not know why. She left without him, and Gurung went to the police to tell them that he was a "criminal" and "terrorist" because he was living off his wife's income. Nepali society is patriarchal, and the man is expected to be the breadwinner.

Police confirmed that on the day in question, Gurung entered an Old North End deli and said he needed the police because he had committed an act of domestic violence the previous day and was having mental health issues.

Officers investigated, searching the couple's Old North End home for signs of violence. They also interviewed Khadka at the Shelburne Road hotel where she worked, Police Chief Brandon del Pozo said. Khadka said her husband could be "slipping off his meds," del Pozo said. She said she didn't think Gurung had committed a crime against her the night before, and she had no visible injuries.

Gurung, meanwhile, asked police to take him to the UVM Medical Center, and they did, according to del Pozo.

A spokesperson from the medical center declined to discuss Gurung's hospital stay, citing federal privacy statutes. Del Pozo has said the attack occurred shortly after Gurung, who was voluntarily admitted, asked to leave the hospital. Khadka came and picked him up, according to the police chief.

Officer Moyer said there were no pending criminal charges against Gurung prior to the cleaver attack. Speaking broadly, she said she's noticed that Bhutanese men accused of domestic violence frequently also abuse alcohol.

By Suk's account, Gurung, who worked in construction in Nepal, had been looking forward to being resettled in the U.S. But his behavior changed just a few months after he arrived in Vermont. "He didn't talk about how hard life in the United States was," Suk said. "But he just started feeling scared of people."

Mental health screening is part of the medical assessment that all refugees undergo overseas before being resettled, said Martha Friedman, the refugee health and health equity coordinator at the Vermont Department of Health. Once they're in Vermont, they undergo another round, Friedman said.

A group of physicians conduct the evaluation based on the standards set by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. "Studies have shown a high prevalence of depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, panic attacks, somatization and traumatic brain injuries in refugees," the CDC says on its website.

Bhutanese refugees in particular seem prone to self-harm, according to Jonah Meyerhoff, a doctoral student of clinical psychology at UVM. CDC data from 2012 show that the suicide rate among Bhutanese refugees resettled in the U.S. is 20.3 per 100,000 — nearly double that of the rest of the U.S. population.

Gurung was hospitalized for a couple of weeks after he tried to end his life in November 2015, according to Suk. After being discharged, Suk added, Gurung found it hard to hold a steady job.

At one time, he had been doing seasonal work at Shelburne Farms. Son Gurung, Suk's mother-in-law, worked with Gurung there and recalled that he was very quiet. "He was such a nice guy in Nepal ... I don't know what changed him," she said.

At a previous job — at a coat factory in St. Albans — Gurung didn't talk to anyone, avoided eye contact and would sometimes cry, a coworker told Dhakal.

"Everybody was scared to ask, so nobody spoke to him," Dhakal said, recounting what he had been told.

Khadka had participated in some events organized by the Vermont Hindu Temple, Dhakal said, and some Bhutanese business owners in the Old North End knew her. There was no indication — from the people Seven Days interviewed — that she ever sought professional help. Connecting Cultures, a clinic based on the UVM campus, provides specialized mental health services for refugees. The Community Health Centers of Burlington recently started a group therapy program for Nepali women.

As for Gurung? "We don't know anything about this gentleman," Dhakal said.

Since the attack, community members have rallied around the surviving family members. The manager at the hotel where Rimal works started a GoFundMe page to raise money for the family. Dahal praised Chandra Sharma and his wife, Purnima, for taking Rimal and his granddaughter into their home even though they didn't know each other. Rimal's wife was discharged last week and is now recuperating at the Sharma home. She has started to eat "a little bit of food," and the visiting nurses are treating her wounds, said Rimal.

"It's very important that we help this family transition out of this," Dhakal said.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.