- File: Derek Brouwer

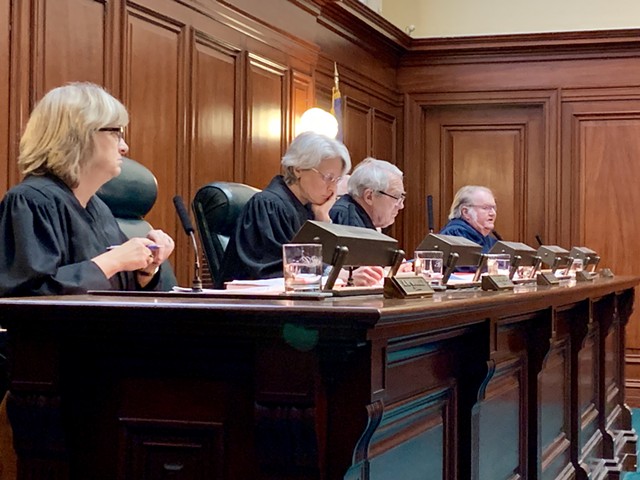

- The Vermont Supreme Court earlier this year

The Vermont Supreme Court has sided with a man who sued the Burlington Police Department for charging him a fee to view an officer’s body camera footage.

In its 3-2 ruling, the state’s highest court reversed a decision by Washington Superior Court Judge Mary Miles Teachout, sided with Burlington man Reed Doyle and declared “that state agencies may not charge for staff time spent responding to requests to inspect public records pursuant to the [Public Records Act].”

In 2017, Doyle claimed to have witnessed a Queen City officer use excessive force against young teens in Roosevelt Park. He sought a court order requiring the department to let him view body camera footage from the incident without charge.

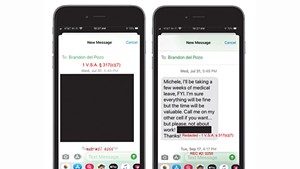

But the department denied the request. When Doyle appealed the decision, Burlington Police Chief Brandon del Pozo agreed to let him view a redacted version of the video. But altering the footage would require making a copy of the original. That would require staff time for which Doyle would need to pay, del Pozo said at the time.

The American Civil Liberties Union of Vermont sued on Doyle’s behalf, but Teachout found in favor of the police department in August 2018. The ACLU appealed the decision to the Supreme Court in October that year. The organization even picked up support from Secretary of State Jim Condos, Vermont's primary public records custodian.

In the amicus brief he filed in January, Condos contended that the lower court ruling would "embolden" public agencies to levy even more charges on those who want to inspect records — including media outlets.

"Pricing out the press," he wrote, would "render transactions of government more invisible, further diminishing accountability."

In interpreting both the public records act, and legislative intent, the high court appeared to agree.

“Furthermore, the PRA explicitly directs courts to ‘liberally construe…’ the Act to ‘provide for free and open examination of records,’” the majority wrote, citing state statute. “‘[T]he Act represents a strong policy favoring access to public documents and records.’”

Chief Justice Paul Reiber, recently retired justice Marilyn Skoglund and retired justice Brian Burgess formed the majority. Burgess was sitting in for Justice Beth Robinson.

Justices Harold Eaton and Karen Carroll dissented.

"I find little, if any, support for plaintiff’s and the majority’s position that reimbursement for staff time is unavailable when a requester seeks to inspect a record without obtaining a personal copy of the record, irrespective of the amount of time it takes agency staff to redact exempt information from the requested record and create a copy,” Eaton wrote in his dissent. “In either case, the request requires the production of a copy.”

That was Chief del Pozo’s original argument, too. In order to respect the privacy of children and minors, del Pozo said in January, his department followed the ACLU's model policy for redacting body camera footage, which states that the department should retain an unedited version of the video. In other words, the redacted version is a copy of the record, he said, and should therefore be treated as such under public record law.

But the majority interpreted the public records act to mean a copy is "a record that the requester could keep and review wherever and whenever the requester chooses."

Inspecting a record is different, the court ruled.

In a written statement issued by the ACLU, Doyle applauded the decision.

"Body cameras are meant to hold police officers accountable for their actions — but we can’t do that if we put up roadblocks that limit people’s ability to review the footage," he said. "The Court’s decision restores my trust in our ability to keep public officials accountable."

ACLU staff attorney Lia Ernst echoed Doyle's sentiment.

“This decision is an affirmation of the core values we as Vermonters hold dear — that our democracy requires government transparency and accountability," she said in the written statement. "Too often, state agencies fail to abide by those values and the letter of the law in denying members of the public access to public records."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.