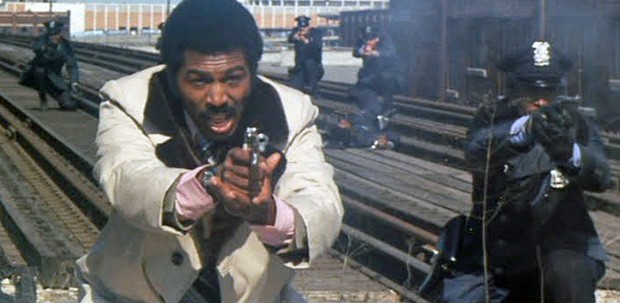

- General Film Corporation / Rolling Thunder Pictures

- Hari Rhodes in the climactic scene of Detroit 9000

That’s not to say that Tarantino hadn’t already made a point of impressing his rich and diverse tastes in cinema on his audience. Few other filmmakers so self-consciously quote from and refer to other movies; indeed, that referentiality is a key aspect of Tarantino’s directorial signature. Part of what makes Tarantino such a fascinating and important director is that he’s as likely to quote from a European art film from 1962 as he is to cite an obscure 1970s American B-movie or a Hong Kong martial-arts film.

I’m on the fence about Tarantino (I like as many of his films as I dislike), but I strongly admire the way that he blurs the artificial line between “high” and “low” art. I believe he borrows this technique from Jean-Luc Godard, one of his great inspirations and probably the greatest cinematic magpie of them all. In almost any given Godard film, the director manages to cite everything from post-Impressionist painting to obscure Hanna-Barbera cartoon characters. Both Godard and Tarantino are essentially, and very intelligently, postmodern in this way, implicitly arguing that any and every element of international culture is fair game for all artists.

As far as I know, Tarantino does not specifically cite Detroit 9000 in any of his films, though he does include a memorable line of its dialogue on the soundtrack to Jackie Brown. Clearly, though, he admires the film, as he hand-picked it for rerelease under the Rolling Thunder banner.

And, though this was never really in doubt, I must say that the man has some good taste. I’ve seen five of the six Rolling Thunder rereleases, and three of them are bone fide masterpieces: Lucio Fulci’s The Beyond, Takeshi Kitano’s Sonatine and Wong Kar-Wai’s Chungking Express. I like Jack Hill’s Switchblade Sisters, too, as well as Detroit 9000 itself. I still haven’t gotten around to seeing the 1977 Shaw Brothers monster movie The Mighty Peking Man, but I’ll get to it one of these days.

Nor is it particularly visually distinguished. In its lighting, cinematography and editing, it resembles nothing so much as an episode of a 1970s cop show like "Starsky & Hutch" or "Baretta." No surprise, as director Arthur Marks helmed several episodes of various cop shows in the ’70s.

Yet Detroit 9000 possesses a couple of unexpected flourishes, one narrative and one thematic, and I’d hazard to say these are the qualities that make it a favorite film of Tarantino’s.

Sometimes lumped into the quasi-genre of “blaxploitation,” Detroit 9000 certainly does not fit that category. Structurally, it has more in common with film noir, most crucially because its story would not cohere without the information revealed in a flashback — and a film can’t be noir without a flashback. Not that flashbacks are particularly difficult to pull off, but this one represents a certain level of thoughtfulness in story structure that is fairly uncommon in cop films of the 1970s.

Another, and more striking, quality that Detroit 9000 shares with film noir is its tone of grim ambiguity. (Spoilers follow, but the film is 43 years old, people.) When the film ends, it deliberately leaves open a very important question: Was Detective Danny Bassett, one of the protagonists, about to crack the case he was working on, or was he about to abscond with a suitcase filled with half a million dollars in jewels? The question remains unanswered because Bassett dies before he can reveal his intentions.

I was very surprised by this ending, given that cop/detective films like this one rarely fail to answer such important narrative questions. In its embrace of ambiguity, Detroit 9000 resembles the European art films that have inspired Tarantino.

As I suggest above, the film is also notable for foregrounding — and being unusually plainspoken about — the fractious nature of American racial relations in the 1970s.

The story revolves around the heist of the war chest belonging to a black politician who has just announced his candidacy for Michigan’s governorship. One black and one white policeman are assigned to the case, and they spend as much time discussing the racial politics of the crime as they do following up on leads.

Bassett, the white cop, says at one point that he’s operating a race-blind investigation, because a felony is a felony; he catches flak for this from his gruff supervisor. Characters joke that the mixed-race team of criminals is “integrated”; racial slurs are bandied about in both friendly and unfriendly ways. The film presents the issue of race as a complex, ever-shifting, insoluble one that informs nearly everything that takes place in the city of Detroit. In the 1970s, that probably wasn’t far from the truth.

- General Film Corporation / Rolling Thunder Pictures

- Looks like every police station in every 1970s cop movie, doesn't it?

And this seems correct to me. Every one of Tarantino’s films takes on racial matters head-on, often to the point where they make audiences uncomfortable. Django Unchained is the most obvious example, but there’s not a film that Tarantino has directed that doesn’t address, in one way or another, the issue of racial tension in America. I haven’t been able to find a statement from QT about why he chose Detroit 9000 for reissue, but I’d bet it has a great deal to do with its candor about race.

I realize that I’m viewing Detroit 9000 strictly though a Tarantinian lens, which isn’t quite fair. Though I’ve remarked that the film is stylistically unexceptional, that’s not entirely true. On reflection, I found an unusual and compelling editing pattern in the movie, though I can’t be sure that I’m not Reading Too Much Into It.

Detroit 9000 opens with the heist. Marks cuts back and forth between two events: people gathering in a hotel ballroom for a gala event; and the team of crooks silently spreading through that same hotel to cut the power, tie up security guards and so forth. This back-and-forth method is usually called alternating editing or parallel editing, and it’s often (semi-accurately) attributed to D.W. Griffith, who, like Marks in this case, uses it to create narrative tension. It grants a certain omniscience to the viewer, who can see two events unspooling into eventual conflict. It’s an old but effective trick.

Toward the end of the film, when the cops have finally tracked down the criminals in their hideout, Marks uses the “opposite” method of editing in a striking manner. Four criminals, holed up in an abandoned building near a railyard, run in four different directions as soon as the cops show up and give chase. Rather than alternating among some or all of the four, to show each of these chases unfolding at the same time, Marks chooses to show each chase in full, one at a time. Criminal A runs, hides, shoots and is apprehended, and then we see roughly the same order of events for Criminals B, C and D in succession.

- General Film Corporation / Rolling Thunder Pictures

- Alex Rocco and Hari Rhodes on a stakeout in Detroit 9000

Yet I liked the “one at a time” editing method in this case, in part precisely because it shows the director avoiding the temptation to repeat a fairly straightforward pattern. The two editing methods impart a certain variety to the film’s storytelling.

As well, I found that the “one at a time” method did, to my surprise, create narrative tension — that tension simply had a different object or end. Watching scenes that use alternating editing, we ask, “When are these two actions going to collide?” Watching the method Marks uses for the capture of the four criminals, we instead ask, “OK, they got this guy — but can they get the next? And the next? And the next? What happens if any one of them evades capture?” It’s a different kind of mounting tension and, in this case, an effective one.

For better or worse, Detroit 9000 will probably always be viewed through the Tarantinian lens. His presence is too strong and his reputation as a tastemaker too important for it to be otherwise. Yet the film is sufficiently unusual and well made to stand on its own.

Speaking of...

-

Student Film Documents Failed Plan to Cut Books From Vermont State University Libraries

Apr 29, 2024 -

A New Film Explores Vermont’s Unsung Modernist Buildings

Mar 20, 2024 -

A Film Critic Pays Final Respects to the Palace 9

Nov 11, 2023 -

Director Jay Craven Wins 10th Annual Herb Lockwood Prize

Oct 21, 2023 -

Book Review: 'Save Me a Seat! A Life With Movies,' Rick Winston

Aug 30, 2023 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.