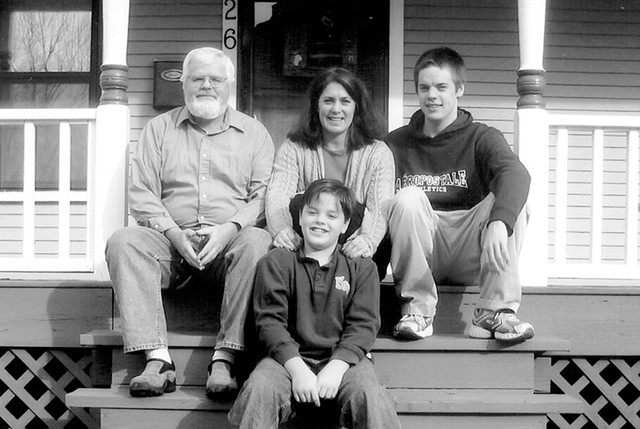

- Courtesy Of Bill Hickok

- Clockwise from top left: Bill Hickok, Patti Rooney, Justin Hickok and James Hickok

It took Bill Hickok five days to write his wife's obituary. Sitting with pen and paper at the kitchen table in his Burlington home, Hickok wiped away tears as he revised it again and again. But there's one thing he never changed. He defied convention and was brutally honest about how she died.

"Patricia A. Rooney, 57, of 26 Fletcher Pl., died by her own hand, on December 13, 2017," reads the account, published April 22.

It describes Rooney's struggle with depression and anxiety that set in suddenly about three years ago. Fear and gloom ate away at the Burlington native, who had been the beating heart of a huge network of family and friends. Treatment did not help.

"Patti was one of those that was resistant to all the new drugs," the obit read. "For 2 and 1/2 years Patti fought a giant adversary and at the end was exhausted and left defeated. The family is not ashamed; we are proud."

In an interview, Hickok said, "I wasn't willing to have the end of her life be a euphemism. It seemed like lying to me. It's a part of life. There's a lot of ways people die, and this is one of the ways, except it's often accompanied by shame."

Rooney's family and friends have told him they loved the unusually candid obit. Mental health experts noticed, too.

"It's very brave of this family to do that," said Laurie Emerson, executive director of the Vermont chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness. "Once you get to that acceptance stage and can start talking about it, that's what's really healing for people. They've opened that door so that people will feel it's OK to talk about it."

The obit also resonated with members of the public. Hickok got a snail mail card from an Essex Junction woman he doesn't know, telling him she was moved by what she had read.

Others chimed in online.

"While I don't know your family, or Patti, I applaud you for so bravely talking about her illness," one commenter wrote on Legacy.com. "It affects more families than we know, and I hope by sharing you have helped another person and their family."

Suicide has long been a leading cause of death. But it is seldom discussed, and few suicides get media attention. In 2015, 102 people killed themselves in Vermont, according to the most recent Department of Health report. It said the state has a higher rate of suicide, 14.3 annually per 100,000 residents, than the 13.7 national average.

Experts say there are signs that the stigma is eroding. JoEllen Tarallo-Falk, executive director of the Vermont Suicide Prevention Center, said she has seen a few obituaries in recent months that included details of the deceased's mental health problems.

"It makes it a lot easier for everybody who loves that person and was in that network — nobody has to play guessing games," Tarallo-Falk said. "You can readily show compassion and caring for the people who are most affected, without worrying about saying something wrong."

A similar trend in obituaries has spread the word about drug abuse. As Seven Days reported in April 2016, some families have used them to document fatal drug overdoses in an effort to erase the stigma of addiction.

Three days after the Burlington Free Press published Rooney's obituary, Seven Days ran the obituary of 35-year-old Waitsfield native Kate Nicholson, whose body was found on April 9 in the water at Texas Falls in Hancock. Her mother, Marsha VanLeeuwen, wrote her obituary. It says Nicholson did well in high school and college until "mental illness began invading her mind and took over her aspirations."

"Always a fighter, she didn't want this illness to get the best of her, but it did, and she struggled with that knowledge every day," the obituary reads.

Like Nicholson, Rooney had good years before her mental health deteriorated. Growing up in Burlington, Rooney was a straightlaced kid who made friends easily, said her younger sister, Laurie. She got good grades and was always home for curfew. When a youthful Laurie once snuck into the family's second-floor window after a late-night party, Rooney lightly scolded her: "You smell like alcohol."

"She was my protector," said Laurie, whose last name is now Kotorman.

Rooney graduated from Burlington High School in 1978 and took a job at the Burlington branch of the insurance and investment firm Mutual of New York, where Hickok was a hotshot salesman. She reminded him of a young Liz Taylor. During an after-hours gathering of coworkers, they found themselves the last two at the end of the night.

Soon, they were inseparable. The couple wed in 1986 and had two sons: Justin, now 31, and James, 22.

Rooney went on to work full time for 31 years as an office manager at what is now the Cain Associates Financial Group. At home, she doted on her boys, cleaned the house, baked cupcakes for countless birthdays and documented everything in jam-packed scrapbooks, family members said.

She was irrepressible and gregarious, the life of any party. Hickok teased her about her unwillingness to embrace her constitutional "right to remain silent." When they went out, she was quick to chat up old friends or even strangers.

And then, seemingly overnight about three years ago, Rooney's light went dark. She withdrew from her friends, sometimes didn't answer her sister's calls and spent most of her time at home. Her frequent Facebook updates ceased. Friends began contacting Kotorman, asking what was wrong.

Rooney had no outward history of mental illness, but the anxiety and depression that set in at age 55 morphed into full-blown psychosis; she suffered delusions, Hickok said.

Her family has means. And the University of Vermont Medical Center is visible from the couple's living room window. And yet, a succession of doctors and their endless combinations of medicines couldn't fix Rooney.

Hickok remembers his wife telling him a couple of summers ago that she had tried to drown herself in the bathtub and inhaled water. She feared she'd damaged her lungs and said she needed to be checked out at the hospital.

That prompted a 90-day inpatient stay at UVM. Rooney underwent electric shock treatment, a last-ditch measure intended to trigger brief seizures to ease symptoms of severe depression.

She was released in October 2016, and it seemed at first as if she had made a miraculous recovery: Rooney was back to her old self. In mid-December, she and her family spent a day chopping down a Christmas tree, one of her favorite traditions. But the next day, Hickok said, the switch flipped once more.

The following year was full of doctor's appointments. Rooney grew more sullen and quiet, almost "shutting down," Hickok remembered.

On the afternoon of December 14, 2017, Hickok couldn't find his wife. He checked the bedroom; it was empty. Hickok called Kotorman and asked, "Have you seen Patti?"

Police searched on foot and by helicopter. Within the first few hours, Hickok instinctively told himself, "Patti is in the Winooski River."

Police posted missing-person flyers around Burlington and issued press releases. Her image appeared on the evening news.

Months passed before Rooney's body was found in the Intervale on April 11. Authorities think she jumped from the bridge linking the Onion City to Burlington and was swept away in the Winooski River's icy current. She had left home without a coat or hat.

Her family still grasps for answers. They suspect that some combination of years of stress and the hormonal changes brought on by menopause started the problem. But they accept that they will never know.

If they couldn't say exactly why she died, they were determined to be up-front about how it happened.

Kotorman read Hickok's draft obit and approved of the disclosure. She added the years Rooney graduated high school and got married. She also slid in additional details, noting that Rooney had a "very large heart" and "great style and flair."

But it was Hickok's voice in the obit.

Writing it "started out as a responsibility, then it became part of the grieving process," he said. "It ended up being a love letter to my wife."

After five days of revisions, Hickok finally thought he was done. But suddenly, one final line came to him. So he sat back down and revised the ending.

In the following weeks, friends would tell him it was their favorite part.

It read: "Au revoir, dear Patti."

Comments (3)

Showing 1-3 of 3

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.