- Sean Metcalf

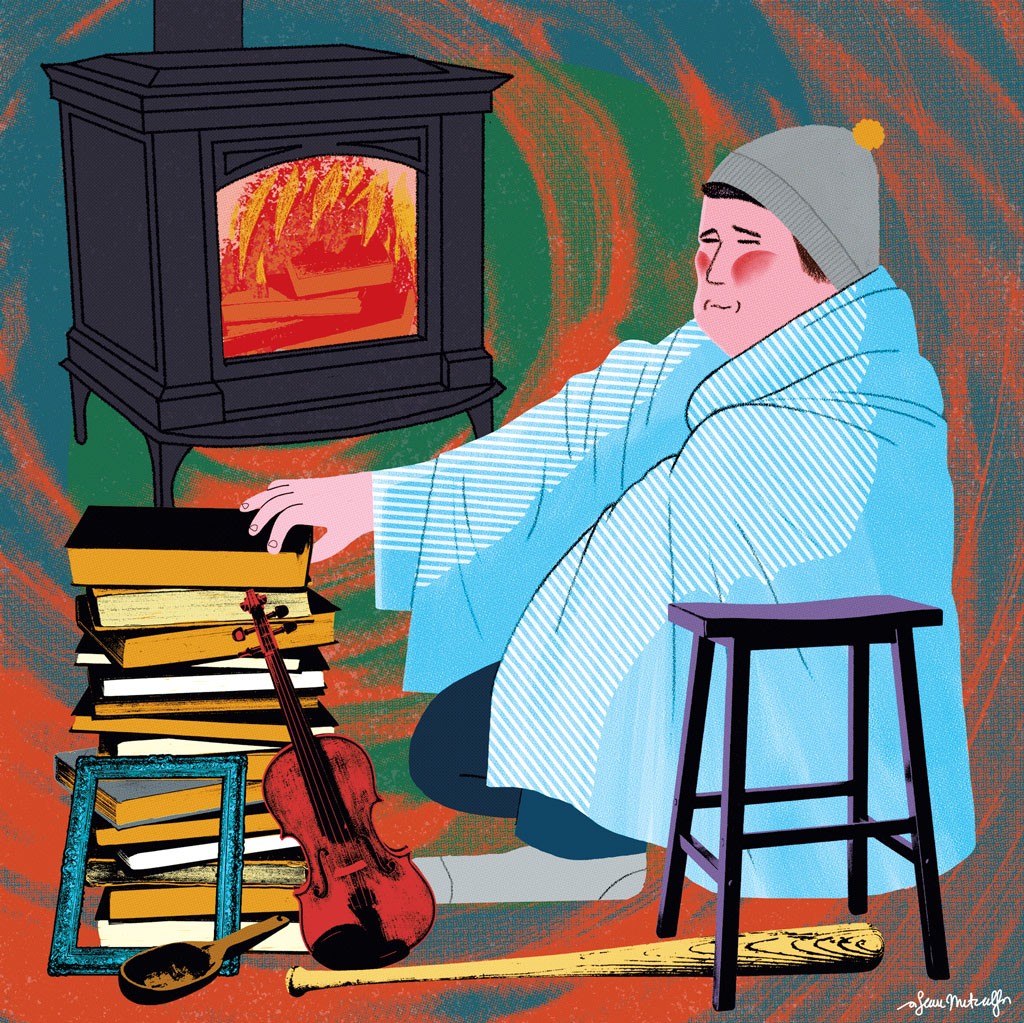

Last June, my family and I moved from Colchester to Charlotte, which took us off the natural-gas pipeline and into the land of propane tanks and woodpiles. As I admired my neighbors' impressive stockpiles of split and seasoned cordwood, all stacked with architectural precision, most told me they heat their homes with a combination of propane and wood, relying more heavily on the latter whenever propane prices soar.

Heating with wood isn't preferable just because it's local, renewable, eco-friendly and pleasing to the eye; it's also cheaper. At least, normally it is, when supplies are abundant.

And it's a popular option in these parts. With more than 80 percent of Vermont covered in trees, many of them hardwoods, the Green Mountain State is a veritable Saudi Arabia of biomass. Not surprisingly, Vermont has the highest per-capita reliance on wood as a primary heating source of any state in the country. This year, more than one in three K-12 students in Vermont began the school year in a building heated with wood.

Hence I was stunned to learn, upon purchasing a new woodstove in August, that seasoned firewood isn't just pricier this fall than it's been in years. It's also harder to find. Much harder.

What happened? Has the emerald ash borer, which has killed tens of millions of ash trees from northern Québec to southern Georgia, finally gained a foothold in our verdant woods?

Nothing of the sort. By all reports, Vermont's forests are as healthy and productive as ever. According to Paul Frederick, a wood utilization forester with the Vermont Division of Forestry, in the past five years Vermont has harvested, on average, more than 8,000 cords annually from state lands alone.

After many fruitless phone calls and emails, I learned that a confluence of other factors has left me heading into the winter without two sticks to rub together. They include last year's longer, colder winter; higher prices being offered at regional pulp mills; the opening of new wood-pellet factories and biomass plants; and a shrinking workforce of loggers, who increasingly resemble the membership ranks of AARP.

Going DIY and burning freshly cut wood wasn't an option. As my salesman at the Chimney Sweep Fireplace Shop in Shelburne reminded me, that's a surefire way to choke my neighbors in an acrid cloud, set off my smoke detectors and eventually accumulate enough creosote in the chimney to burn my house to the ground.

Marshaling my investigative skills to gather firewood intel, I turned to Vermont's hyperlocal source of neighborhood info, Front Porch Forum. I put out the e-word that I was looking to score at least a cord that had been seasoned at least one year. Instead, I got back half a dozen emails from fellow Charlotte residents who all said, in effect, "If you find some, let us know. We're out, too!"

One neighbor suggested I contact Larry Hamilton, Charlotte's tree warden since 1996. Hamilton spent 30 years teaching forestry at Cornell University and another 13 years at a tropical forestry institute in Hawaii. He knows the location of nearly every tree in Charlotte that's more than 80 years old and has planted more than 400 roadside saplings over the past six years. No wonder he's become Charlotte's de facto adviser on all things arboreal.

I wasn't the first person to tap him for firewood connections. A few years ago, after years of replying to individual inquiries, Hamilton finally compiled a list of local suppliers and posted it on Front Porch Forum. He promptly forwarded it to me, along with seemingly encouraging news.

"A lot of people have gotten into the firewood business in the last two years," Hamilton reported. "Four or five years ago, there were maybe five people in Charlotte [selling it]. Now, there's a lot of them." He said I could expect to pay $250 to $275 for a "short cord" or "stove cord." That's similar to a standard cord — four feet wide, four feet tall and eight feet long — only the logs are cut shorter, to 16 inches, to fit in a typical woodstove.

But as I rapidly burned through Hamilton's long list of dealers, coming up empty each time, it became apparent that price would be less of an obstacle than availability. Hoping to avoid my least desirable option — buying kiln-dried wood from a local lumberyard at nearly $500 a cord, including delivery — I widened my search radius to include some regional loggers. Surely, if anyone had wood, they would.

It's time for a word about one of Vermont's largest but arguably least-appreciated industries: forest products. Milk, cheese, maple syrup and Ben & Jerry's ice cream may be Vermont's iconic commodities, along with patchouli-scented Phish fans and socialist presidential wannabes. But Vermont's timber industry contributes more to the state's gross domestic product than even agriculture — not including the illegal marijuana trade, which, technically speaking, could be considered a forest product, too, as that's where much of it is surreptitiously grown.

In fact, when measured collectively, Vermont's wood-products industry is second only to electronics in total manufacturing revenues, and pays the highest manufacturing wages outside Chittenden County. Need further convincing of its importance? As the bumper stickers I often saw while living in Montana put it, "Don't like logging? Try wiping with a pine cone."

Yet, for all their contributions to the state's economy, loggers don't get their due respect, especially considering the hazards of their job. According to 2014 figures from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, work-related fatalities among loggers in 2013 were the highest since 2008 and the highest that year, per capita, of any industry in the country — exceeding commercial fishing, mining, construction and aviation.

What's all this got to do with my inability to build a crackling fire? Turns out, more than half of Vermont's timber workers are older than 45; one in four is older than 55. And as all those graying woodchucks retire, very few are being replaced by younger bucks who can drop the trees that will feed Vermont's growing number of woodstoves.

Forester Frederick confirmed that, because fewer loggers headed into the woods this year to cut timber, supplies were smaller than they've been in the past. Exacerbating the problem was the long, cold 2013-14 winter, which caused suppliers to burn through their back inventories.

"Last winter, everyone burned everything they owned," noted David Bessette, a 51-year-old Williston logger. "They were just about ready to start chopping up the back wall of the barn and throwing the furniture in there, too."

As a result, many eager beavers snapped up extra cords this summer.

Bessette, who's been logging for more than 25 years, has heard from frustrated customers who can't find firewood this year. He explained that loggers are seeing increasing competition for low-grade lumber from regional pulp mills such as International Paper in Ticonderoga, N.Y. Also hungry for wood are biomass plants, including Burlington Electric Department's Joseph C. McNeil Generating Station; a new 75-megawatt biomass energy plant in Berlin, N.H.; and a new chip-burning boiler in Fort Drum, N.Y.

"They're chewing up wood that wasn't being chewed up before," Bessette added. "And they're trying to buy the same wood you're trying to buy."

Adam Sherman, of the Biomass Energy Resource Center in Burlington, wasn't convinced that new biomass plants were cutting into my potential woodpile. But he did confirm Bessette's observation about the paper mills.

"In the last six months, we've seen a pretty dramatic uptick in the hardwood pulp demand," Sherman said, "which is a competing supply to the firewood market."

Bessette told me he'd gladly sell me a cord if he had one (he didn't), but he admitted that he has reasons for favoring larger markets. In his business, when he's got a truckload of low-grade timber and a paper or pellet mill willing to weigh his truck and pay him for the entire load, that's an easy sell.

By contrast, selling firewood to a homeowner involves more sorting and segregating so Bessette can give his customer "that most picture-perfect, hand-splittable wood, with no mud or dirt on it." Add in the time and hassle of backing a logging truck down a long, winding driveway, where he runs the risk of caving the front lawn into the septic tank, and it's easy to understand why peddling firewood isn't high on many loggers' to-do lists.

Since I kept coming up empty, I finally reached out to the one fallback source everyone had recommended: A. Johnson Company lumberyard in Bristol, which sells kiln-dried firewood. Dave Johnson, a fifth-generation wood supplier, confirmed that the dwindling number of loggers in the woods has "positively" affected his inventory. While lower supplies and higher demand mean higher prices for Johnson's products right now, he said he's troubled by the potential consequences of the wood shortage down the road.

"We've got a number of customers," Johnson said, "who have told us that if we stop [selling firewood], unless they can find a replacement supplier, they'd get rid of their stove."

Personally, I'm not ready to go to such extremes yet — or bite the bullet and shell out $400 for a cord of kiln-dried, certified emerald ash borer-free timber. After all, the damn woodstove hasn't even been installed yet.

But if you've got any, I'll be the one standing along Route 7 with a tongue-twister sign that reads, "How much for a truck of woodchuck's wood?"

This Stuck in Vermont video features Pat Stanley, a firewood dealer in Vermont for 24 years.

Comments (9)

Showing 1-9 of 9

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.