- Tim Newcomb

Martha Staskus first visited a clearing half a mile up a dirt road in Stamford to assess whether the remote southern Vermont property would be suitable for a solar array. Looking south across the forested valley, Staskus, the chief development officer for Norwich Solar, sensed another opportunity.

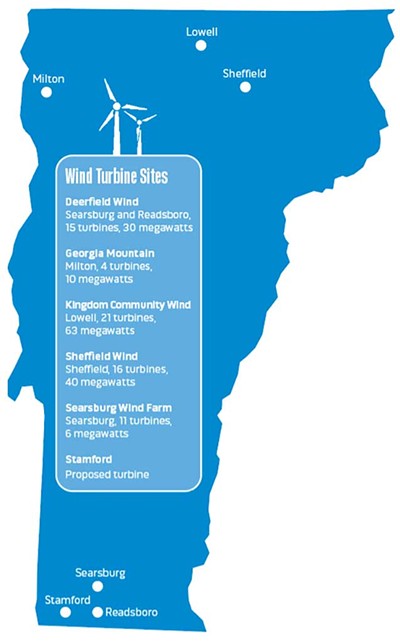

She surveyed with pride the 19 turbines of the Hoosac Wind Power Project just over the state line in Massachusetts. While working for a different company, Staskus helped develop Hoosac, as well as 26 Vermont turbines nearby, in Deerfield and Searsburg.

So she knew that strong, steady winds buffet the mountainous area. She told her boss, Norwich Solar CEO Jim Merriam, "Man, it would be nice to do a wind project there," she recalled.

Nearly two years later, Staskus is preparing to ask regulators to allow the construction of a 2.2-megawatt wind turbine on a knoll just north of that forest clearing. The 500-foot-tall turbine, which would provide enough power for about 925 homes, would be the tallest structure of any kind in Vermont.

There hasn't been a new utility-scale wind project permitted or built in Vermont since Deerfield's 15 turbines began spinning in 2017. Several subsequent proposals have stalled, which wind advocates blame on a hostile political and regulatory climate.

In 2020, David Blittersdorf, the chief executive officer of AllEarth Renewables, declared wind energy development all but dead in Vermont when he couldn't secure a permit for a 2.2-megawatt turbine on a farm in the Northeast Kingdom.

"We are in real trouble as a state if we can't build a single wind turbine in a flat cornfield, hosted by a dairy farmer that wants the project built to help keep the farm going," Blittersdorf said at the time.

The Stamford project represents a new test of Blittersdorf's wind-is-dead prediction.

Staskus argues that the powerful turbine would reduce the burning of fossil fuels for electricity, generate needed tax revenue for the town and have limited impact on neighbors.

"Wind energy in the southwest part of Vermont has been demonstrated to be an important resource contributing to the state's renewable energy goals," she said. "Here is an opportunity for Stamford to continue to be part of that movement benefiting all Vermonters."

The company has already secured a long-term contract for the electricity under the state's Standard Offer Program, which creates incentives for renewable energy projects by requiring Vermont utilities to purchase the power at a specific, desirable rate. Staskus declined to say what the Stamford project would cost but said it would be limited to a single turbine. Though it would not enjoy the same economies of scale as multi-turbine installations, "At this point, it pencils," she said.

She is now preparing to seek formal approval from the state Public Utility Commission. Her application, due by December 15, will kick off a public process expected to stretch well into next year.

Norwich Solar shared preliminary details of the project over the summer with town officials and neighbors — quickly prompting a litany of objections that echo those raised about past wind proposals.

Neighbors wonder whether their sleep would be disrupted, their views marred and their property values deflated. Town officials decry the turbine as too close to homes and out of step with the town plan. Others worry about harm to the fragile hillside ecosystem and wildlife habitat from the steep, 1.5-mile access road that would need to be built to reach the knoll. Activist Annette Smith, executive director of Vermonters for a Clean Environment, is counseling residents on the most effective ways to make their objections known.

"These turbines are too big," Smith said of contemporary wind development. "The amount of environmental damage and community division and aftereffects they create are all massive for what the benefits are."

The fervid opposition to a single, remote turbine underscores the headwinds that wind energy development faces despite the state's commitment to sharply reducing emissions from fossil fuels.

Wind power advocates say the industry has been stalled by political opposition — Gov. Phil Scott is not a fan of ridgeline wind — and by unnecessarily strict permitting rules, including some of the nation's toughest limits on turbine noise.

"Wind is in a coma in Vermont," said Nicholas Laskovski, senior manager of wind energy operations for Greenbacker Renewable Energy, a New York-based investment company. Greenbacker owns Georgia Mountain Community Wind's four turbines on a ridge northeast of Milton.

Sound rules imposed on new wind projects in 2017 have suppressed wind development, he said. The rules require that turbine noise measured 100 feet from a home must not exceed 42 decibels during the day and 39 at night. Forty decibels is about the sound level of a quiet library or the hum of a refrigerator.

Those rules would need to be relaxed if wind is to be harnessed on the scale needed to limit climate change, according to Peter Sterling, executive director of Renewable Energy Vermont.

"With a wind sound rule that is quieter than a library, we are not able to build wind in Vermont in a way that would meaningfully help us meet the load demand," he said.

Wind power complements solar by operating well in winter, when days are shorter, and at night, Sterling said. Demand for cheap, clean electricity is only going to increase as more people switch to driving electric cars and heating their homes and businesses with electric heat pumps.

But how turbines look, as much as how they sound, will continue to drive opposition to their installation. Until that changes, the industry will likely be relegated to remote corners of the state, Laskovski said.

"I think Vermonters in general have a very protective spirit of their ridgelines and mountains," he said.

Staskus is betting that her project would not be visually jarring to residents of Stamford, in part because there are lots of turbines there already.

A visual simulation the company prepared from Route 8, three miles south of the turbine site, shows the slender white blades barely peeking over a distant stand of trees. Additional simulations will likely be required for the Public Utility Commission process.

The fact that Stamford is surrounded by wind turbines is cold comfort to some residents who worry their town is already shouldering more than its share of the renewable energy burden.

"You look to the left — windmills. You look to the right — windmills. It's just crazy," said Lisa Gramlin, who lives a little more than a kilometer from the turbine site. "No matter which way we turn, we're already surrounded."

Most frustrating for Gramlin, a writer who lives in the Alpenwald Village subdivision closest to the project, is that the town and Bennington County have planning documents that attempt to bar large turbines from within one kilometer of homes. About nine homes in Alpenwald Village are within that one-kilometer buffer zone, and the developer's decision to push forward with a plan anyway has left many in town feeling steamrolled, Gramlin said.

"Now the town feels like, Wow, we spent two years writing this plan, and now you're not going to even respect it?" she said.

In a letter to the PUC, the Stamford Selectboard objected to the turbine and noted that it had received more than 100 messages of opposition and none of support.

Bill Colvin, the executive director of the Bennington County Regional Commission, said he met with the developers in the spring and "flagged as potentially problematic" the town's one-kilometer rule.

Because Stamford adopted what is referred to as an "enhanced energy plan" in its town plan in 2019, the PUC is required to give "substantial deference" to the town's input, he explained.

Staskus acknowledged that the town plan's residential buffer represents a "potential constraint" but denied that the zone was an absolute prohibition on turbines in those areas. She cited a line from a 2017 version of the plan that says "the need for a drastic shift in current energy trends is undeniable."

Bennington's regional plan calls for 18 to 34 megawatts of new wind power capacity to be built in the county by 2050 to help the state reach its energy goals. Wind maps suggest that Stamford, with its windy peaks and proximity to transmission lines, could carry much of that load. "Not every town has these high ridges that make sense for wind generation," Colvin said.

T.J. Poor, the director of the Department of Public Service's Regulated Utility Planning Division, agrees that wind will need to be part of the state's transition to renewables. But Vermont can avoid erecting lots of new wind turbines on its ridgelines, he said.

"Those goals can be met other ways," Poor said, such as importing wind-generated electricity from elsewhere in the region, including from offshore turbines in the Atlantic Ocean.

Advocates say that may be a pipe dream. A number of those offshore projects are stalled or have been abandoned as interest rates and construction costs soar.

Those setbacks reinforce Blittersdorf's conviction that Vermonters need to look not to Québec or Cape Cod for their renewable energy needs, but right at home.

"We're slow-walking our way off an energy cliff," he said. "And we're going to be destitute if we don't produce our own energy."

Meanwhile, Staskus is hopeful her Stamford proposal will demonstrate that wind development is still possible in Vermont.

Sound and other studies are under way and will be submitted with the PUC application. She hopes the community and regulators can then have an informed discussion about the impacts of the turbine, including the benefits.

"I hope that this is a step in shifting the conversation for more wind in the state," she said.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.