- Rob Donnelly

Believe it or not, I still remember my first Zoom meeting. That's primarily because it was less a meeting and more a virtual dance party hosted by a good friend and DJ. It was very early in the lockdown of 2020, and I was one of dozens of virtual attendees who were all too excited to collectively dance our anxieties away in front of a computer.

It wasn't long before attendees discovered they could easily change their Zoom backgrounds, adding a new level of absurdity. Suddenly we were no longer trapped in our apartments but dancing in the vastness of the Milky Way galaxy. I found myself holding an illustrated book of cat breeds up to my webcam to create the illusion that several felines had crashed our party. By the end of the night, much of the animal kingdom was in attendance, and, for a few fleeting moments, the unbearable uncertainty of the early pandemic slipped from my mind.

In the weeks that followed, Zoom and other online platforms rapidly shifted from a novel way to connect with others to an unavoidable part of daily life. For Vermonters fortunate enough to have robust and reliable internet, the online world replaced offices, classrooms and other gathering spaces.

Performing artists and cultural organizations, hit particularly hard during the pandemic, also had to embrace serving audiences virtually. Events that once took place in packed venues were performed in empty rooms and viewed on the same devices that people used to check email and argue with strangers on social media.

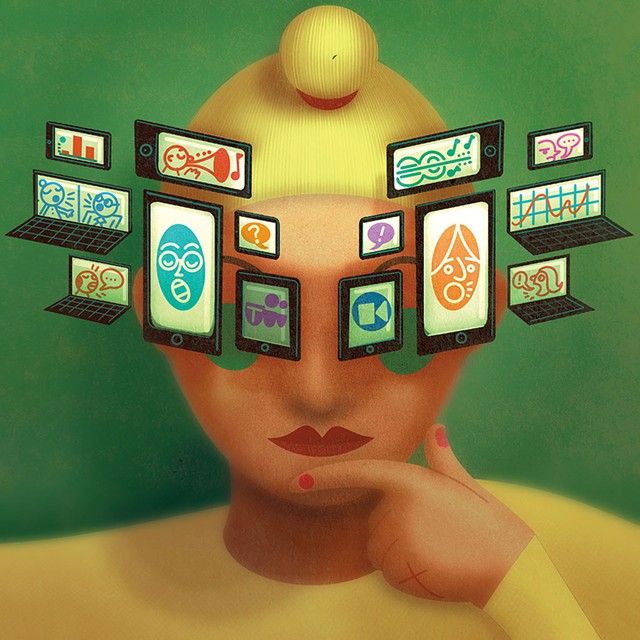

Almost overnight, our relationship with technology drastically changed.

Nineteen months later, what have we learned, and why do many of us feel so damned tired after an online meeting?

It's not just you: "Zoom fatigue" is a thing. In a peer-reviewed study published in February 2021, Stanford University communications professor Jeremy N. Bailenson identified key sources of "nonverbal overload" that can cause exhaustion during virtual meetings.

Imagine an in-person meeting in which everyone is standing right in front of you, looking directly in your eyes. Now imagine that one of them holds up a mirror so you're forced to look at yourself nonstop. Though this could be a scene from a psychological thriller, it's essentially what we experience in every online meeting.

The excessive close eye contact is intense, and seeing oneself for hours at a time is highly unnatural, Bailenson wrote. We also have limited mobility when sitting in front of a webcam, and it's harder to send and receive nonverbal cues, he found.

The cumulative effect is that we're exerting much more mental energy than we realize while videoconferencing. It can cause exhaustion — and could explain why some people still haven't learned to unmute themselves before talking.

Bailenson suggests a number of solutions, such as reducing the size of your virtual meeting window to minimize face size, using an external keyboard to gain distance from the screen, using an option to hide yourself from view, and turning off your camera for a moment and moving around the room.

Want to help the climate while you're at it? An April 2021 study by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Purdue and Yale universities found that turning off your camera can reduce your environmental footprint during a meeting by 96 percent.

Minimizing emissions while potentially improving the mental health and energy levels of employees? I'm no manager, but that seems like a no-brainer.

Vermont arts and culture organizations have learned some other surprising things during the age of virtual gatherings. In April of last year, the Vermont International Film Foundation launched its Virtual Cinema, an online platform that allows users to stream full-length films for a limited time.

"We started offering several new releases a month, and at the beginning people were very, very excited," recalled VTIFF executive director Orly Yadin.

As the months progressed, however, Yadin noticed viewership declining. "People were beginning to get used to the fact that they were just stuck at home viewing," she said. "They were tired of streaming, basically."

Viewers told Yadin that when they did stream content at home, they opted for undemanding things that offered an escape — not the types of carefully curated films associated with film festivals. As someone who rewatched both "Breaking Bad" and "The Sopranos" during lockdown, I certainly understood that choice.

But when VTIFF held an all-virtual festival in October 2020, viewership once again increased. "That showed us that just regular streaming of a title here or there attracts less attention than if you create a whole event around it," Yadin explained. "We have to work extra hard to get people to watch our online offerings."

Last week VTIFF held its latest festival, a hybrid of in-person and virtual screenings. Yadin said in-person turnout was even higher than expected and that virtual screenings accounted for about 20 percent of tickets sales.

Streaming fatigue didn't seem to impact the Vermont Symphony Orchestra, which offered several virtual small ensemble concerts last season. According to executive director Elise Brunelle, each virtual event sold more tickets than the one before it, something she partially credits to commissioning new works.

"A lot of it is around how you market it and how you reach different audiences," Brunelle said. "The big question is, are they going to follow us now to the full orchestra performances?"

The VSO will find out on Saturday, October 30, when it returns to the Flynn Main Stage in Burlington for its first live indoor concert since the pandemic began.

Instead of livestreaming the event, the orchestra plans to release a streamable, edited version two weeks after the concert.

"The most important thing that I've heard was that people really value quality recording," Brunelle said. "If we're going to invest our time and effort in a quality musical performance, it's just as important that we do that with the quality of the audio and video. It's a whole other layer of responsibility."

White River Junction-based theater company Northern Stage has experimented with a variety of virtual offerings during the pandemic, ranging from live readings and discussions to a fully interactive play.

"It was a very meaningful experience for us," said producing artistic director Carol Dunne. "We found that we got a lot closer to a lot of our audience members."

The company, which held its last Zoom event in March, has no plans to return to streaming. "It was a beautiful way to keep people connected to theater during the pandemic," said Dunne, "but it doesn't replace live theater."

Northern Stage hasn't abandoned technology entirely, however. The company's latest production, Junction, is a site-specific "walking play," during which audience members use a cellphone and headphones to be guided to various scenes in White River Junction.

Dunne also noted that many auditions still occur over Zoom.

Every presenter I spoke with said virtual programming helped bring their work to a wider audience. Assuming this impact applies to all patrons, I asked Inclusive Arts Vermont executive director Katie Miller whether she thought that streaming was making the arts more accessible. "Actually, no," she responded in a devastating blow to my preconceived notions of access.

Miller acknowledged that streaming has eliminated transportation barriers and been hugely beneficial to immunocompromised individuals, but she emphasized that technological challenges can be greater for people who live with disabilities.

"There are many things about the online space that are inherently inaccessible," Miller said. "It is almost an entirely visual world."

For people who are visually impaired, it's particularly challenging to navigate virtual events, a difficulty that's compounded if they are hearing screen-reading software while listening to presenters or performers, Miller added. Her organization is partnering with the Vermont Arts Council to offer a nine-month series that starts on November 2 about improving digital access to arts programming for people with disabilities.

Despite their challenges — including the capacity to exhaust us — virtual gatherings seem here to stay. As we continue to find ways to improve our experiences, I'm confident that life may get a little better for us all.

As Miller eloquently put it, "Any accommodation feature that's good for one person is usually good for lots of people."

On that note, I'm off to stare at something other than a screen for a while.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.