- File: Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

Sunlight filtered through the canopy of leaves, illuminating the Hinesburg Town Forest in a soft green glow. The branches of the birch and maple trees stirred in the breeze. Only the occasional warble of a bird broke the stillness.

Chittenden County forester Ethan Tapper surveyed the scene with dismay. The woodland was "a little ecological disaster zone," he declared.

White-tailed deer had ravaged the area, Tapper said as he crouched to examine a cluster of three-inch-high ash saplings in a thicket of ferns. Hungry deer had munched them down to the ground repeatedly, he said. The acres of maple and ash seedlings all around him had been decimated.

As a result, no understory of trees is growing to replace the overstory of 80-year-old maples. The forest is open to an invasion of buckthorn, honeysuckle and other nuisance species. As climate change brings more severe windstorms and invasive bugs, the lack of diversity of native species means the forest will be less likely to rebound after damage, he said.

Anything that impedes a forest's ability to regenerate "is an existential threat," Tapper said. Today, in some parts of Vermont, the state's native white-tailed deer population is one of those threats.

A dramatic 40-year decline in the number of hunters and the spread of "no trespassing" signs barring them from land have allowed the Vermont herd to grow beyond desirable levels in about half the state. The mild winters linked to climate change have boosted the population as well, reducing the winter kill that kept deer numbers in check.

Deer population density

Source: Vermont Fish and Wildlife, Vermont Agency of Natural Resources

Roughly 150,000 deer roam Vermont's woodlands, but they are more concentrated in some areas. In places such as suburban Chittenden County, Grand Isle County and parts of southern Vermont, the combination of a moderate climate, fewer hunters and limited access to hunting grounds has allowed white-tails to thrive.

In those regions, the diagnosis is clear. "We have way too many deer, and we know it," said Nick Fortin, deer project leader at the Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department.

Vermont's herd is not the biggest it's ever been; it spiked to a quarter million in the 1960s. But this time, it might be more difficult to reduce the population to keep it in balance with the natural habitat and human preference. Demographic and cultural shifts have left state officials with increasingly limited options to control the size of the deer herd.

Vermont's bow-and-arrow deer season opens on October 6, and the 16-day rifle season will start on November 10. As hunters prepare to head for the woods, biologists and policy makers are experimenting with a laundry list of deer-management strategies — with mixed success.

In the most deer-dense areas, the stakes for Vermont's landscape are high. Said Fortin: "We need to reduce the deer populations sooner rather than later, or it's going to have long-term impacts."

'It's a Dying Sport'

- Sarah Priestap

- Ray Royce Jr.

Norwich offers a town-size view of what's been happening in Vermont. The Windsor County community has big clapboard houses along Main Street and rural dirt roads where well-to-do retirees rub elbows with professors from Dartmouth College in nearby New Hampshire.

Norwich has the second-highest median income in Vermont — and the most parcels of land posted to prohibit hunting. The area also falls squarely in one of the regions where Fish & Wildlife has identified an overabundance of white-tails.

According to Ray Royce Jr., the town has evolved in gradual but fundamental ways.

Once upon a time, when he drove along the back roads during deer season, the Norwich hunter would see 40 or 50 parked trucks belonging to hunters. Now, he'll spot just three or four.

"You can definitely see it's a dying sport," said Royce, 64, as he sat by a glowing woodstove in his log cabin home one recent afternoon.

A bear pelt and two mounted bucks adorned the walls, along with family photos of men in hunting camouflage. Royce has bagged deer in all but 10 or so of the 52 years he's hunted, he said, but over the decades, he's become less enthralled by the trophy than he is by the less flashy aspects of the tradition.

He recalled with pleasure an afternoon he spent in the woods enticing a mouse onto his lap with bits of sandwich as he awaited a buck. Another day, he was startled to find that coyotes had snuck up on him.

"The things you see in the woods, they stay with you all your life," he said.

His extended family has long gathered for November rifle season as reliably as for funerals and weddings. His deer season crew, some of whom drive up from Connecticut, peaked at two dozen a decade or so ago; last year, about 16 made the trip. The group has gotten older; four have died, and others struggle to stay in the frigid woods for long periods.

And while Royce doesn't yet have grandkids, when they arrive he's not sure they'll be hunters. He'll encourage them, he said, but "kids have a choice."

His family's shift mirrors Vermont's. The number of seasonal hunting licenses declined by 40 percent statewide since 1990, from 105,333 to 62,813 in 2017, according to state data.

Vermont's aging population is partly to blame; fewer young hunters are picking up the sport. Only 10 percent of 20-year-olds bought licenses in 2015, compared to nearly 30 percent of those in their late forties, according to Fish & Wildlife.

Many Norwich families are relatively new to Vermont and come from more urban areas where hunting was not part of the culture, according to Lindsay Putnam, who works for Dartmouth College's Outdoor Programs Office and teaches environmental education at Marion Cross School in Norwich. She's also a hunter.

"There's just not a comfort level or familiarity with hunting," she said. "It's not part of their family culture, and they don't teach their kids how to hunt."

The result is a growing fissure in the town. Hunting has made Dakota Hanchett an outsider, the high school senior wrote in an op-ed in the New York Times in March.

"Going to school can be hard because most kids don't understand how I live," he wrote. "Sometimes I get the feeling ... kids are afraid of me because I own firearms."

Fewer kids are spending time outside at all, Putnam said, pointing to the 2005 book Last Child in the Woods, in which author Richard Louv noted a rise in what he called "nature-deficit disorder" among children.

At the same time, Vermonters are slowly losing access to large undeveloped natural areas. Old farms and forestland are being subdivided into smaller and smaller plots, often with houses and lawns. Between 2004 and 2016, plots of land of fewer than 50 acres with homes on them increased by more than 20,000 parcels — nearly 9 percent, according to Jamey Fidel, forest and wildlife program director for the Vermont Natural Resources Council.

Urban centers, especially in Chittenden County, are sprawling into surrounding rural towns. Grand Isle does not have any privately owned undeveloped forests of more than 50 acres, Fidel said.

That leaves fewer places for kids to experience the natural world, the first step in building interest in hunting, according to Putnam.

The reality — in Norwich and elsewhere — is that "people have a huge amount of land, and they go to the gym," she said.

As the number of hunters has dropped, Royce has also seen attitudes toward hunting shift around Norwich.

When he was a kid, Royce said, his family members would congregate with other hunters each evening at Dan & Whit's general store in town to show off their bucks and trade stories about the day's hunts. These days, he said, the family stays home and butchers their deer in Royce's yard.

People in town "don't like seeing blood," he said.

From Dirt Road to 'Gold Coast'

- Katie Jickling

- A sign on posted land

High up on Bragg Hill Road above Norwich village, it is easy to see the cultural changes that have gone hand in hand with alterations to the physical landscape.

Small farms along the road began failing in the 1960s. Their owners sold and subdivided their land. Forest reclaimed some of the fields, and the new mix of open and wooded land brought more deer. Newcomers moved into the old farmhouses or built new ones. Bragg Hill became the town's "gold coast," as resident Antoinette Jacobson put it, home to doctors, professors and seasonal residents.

Almost all the land along the road is now posted, she said.

Last year, Jacobson, whose 91-year-old mother, Gerry, bought their land on Bragg Hill in 1938, added her 59 acres to the list. A family with young children rents a house on the property; they grew nervous after they saw a hunter fire at a turkey near their chicken coop. Jacobson gives permission to the occasional hunter who asks, but she restricts access to strangers, she said, as "a matter of safety."

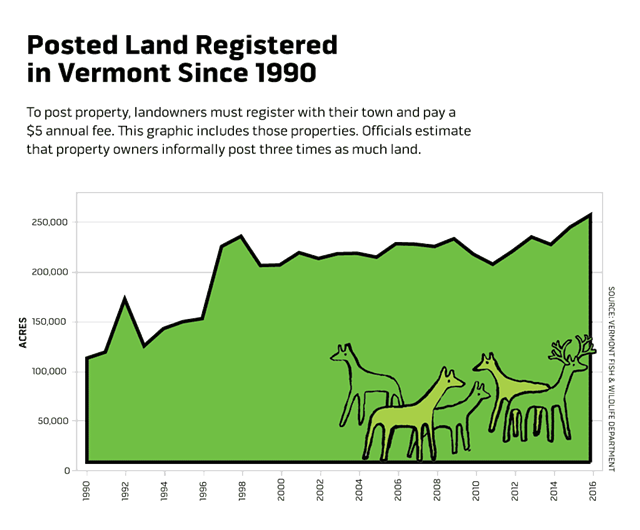

Jacobson is one of 47 Norwich landowners who have posted their land according to the state's rules — hanging signed, dated "no trespassing" notices less than 400 feet apart, and plunking down a $5 annual fee to register with their town. They have plenty of company: Between 1969 and 2016, the number of posted acres in Vermont more than doubled, from 106,000 to 262,000 acres, according to state data.

Fish & Wildlife Commissioner Louis Porter estimated that at least three times as many acres are improperly or informally posted by landowners who don't register their property at a town office or correctly label the signs.

In Norwich, posted lots range in size from a single acre to 400 acres. Among the reasons listed on landowners' forms? Safety, privacy, bad experiences with hunters and, in one case, "LOVE ANIMALS."

Norwich Town Clerk Bonnie Munday said some newcomers "don't educate themselves about why there's a sports season in Vermont." For them, the thought of a hunter parading across their land with a rifle doesn't leave a "warm and fuzzy feeling."

Charlotte Metcalf posted her 400 acres east of the village a decade ago, after two separate hunters shot into her fenced fields of animals on the same day, she said.

She continues to allow about 40 people she knows to hunt on the property. Metcalf said she's sensed increasing frustration from hunters who can't find a place to hunt. Some trespass or poach in protest, she said — which in turn leads to more land getting posted.

"There's an attitude of desperation from people who need that deer in the freezer," she said. "That's understandable, but it's not fair to landowners who want their wishes to be respected."

No Big Chill

- File: Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

Fish & Wildlife information specialist John Hall vividly recalls his survey of a Hyde Park deer wintering yard after a hard winter in the 1970s. More than 40 emaciated fawns lay dead. When he cracked open their thigh bones, gelatinous red marrow poured out, a sign the deer had starved to death.

In past decades, severe winters complemented hunting as the primary checks on a burgeoning deer herd. During one of the worst years in the 1970s, Fish & Wildlife workers found 117 dead deer per square mile in some of the animals' wintering areas that were surveyed, recounted Mark Scott, the department's director of wildlife.

Now, in large swaths of the state, the deep snow and frigid temperatures that lead to starvation are less common. In Chittenden County, Fortin guessed that only one winter in the last decade has been cold and snowy enough to thin the herd.

Together, the milder climate and reduced hunting pressure have allowed the herd to grow to nuisance levels in places such as Grand Isle County, which is now home to 28 deer per square mile, about 50 percent higher than the number recommended by the state.

Residents have experienced the consequences. Allen Hall, owner of Hall's Orchard on Isle La Motte, holds a permit that allows him to shoot four additional deer a year when he catches them eating his apples.

Three years ago, deer ate roughly 30 percent of Bob Buermann's six acres of sunflowers in South Hero. The next year, he planted double the acreage, just in case.

Jane Pomykala, co-owner of Pomykala Farm in Grand Isle, said she always tries to fence her crops in time but has found that in spite of her efforts, deer occasionally manage to devastate her rows of beets or beans.

There are so many deer that the area regularly has the highest success rate for hunters, according to Fish & Wildlife statistics.

Deer are climate change "winners," Fortin said. In turn, they exacerbate the impact of climate change on humans. A larger deer herd, for example, is linked to higher rates of Lyme disease, because deer ticks, which carry the bacteria that causes Lyme, lay eggs and reproduce on deer.

Deer prefer to chow down on native species, which leaves room for invasive plants moving north as the temperature warms. The result is a forest such as the one in Hinesburg — where the trees are all mature and roughly the same size, said Tapper, the Chittenden County forester. In such a deer-ravaged forest, a disease or a storm that can topple a single tree can fell them all.

Hunting for Answers

In Montpelier, policy makers at Fish & Wildlife have a multipronged approach to reducing the deer herd: encouraging people not to post land, nurturing a new generation of hunters and making changes to deer season to increase the take, particularly of female deer.

Eight years ago, the state and the nonprofit group Vermont Coverts teamed up to offer goody bags to new landowners who purchase at least 25 acres. The "welcome wagon kits" include birding CDs, a cutting board, information about wildlife management and land conservation, and some "hunting by permission only" signs.

They hoped to entice property owners to open their land to some hunters, Fortin said.

After eight years, about 50 kits have been distributed, said lands and habitat program manager John Austin.

In 2014, the department went further, implementing a rule that allows game wardens to enforce "hunting by permission only" signs as strictly as traditional "no trespassing" signs.

Hunters have tried to help, as well. When Ed Gallo, vice president of the Hunters Anglers Trappers Association of Vermont, teaches a hunter safety course, he instructs students to ask the landowner for permission — regardless of whether the land is posted. It's part of his effort to minimize bad behavior, he said.

This year, wildlife officials plan to reinvigorate a program that would pair landowners with hunters who need a place to hunt. In the first iteration of the program, Fortin said, hunters were eager to participate, but few landowners volunteered.

Scott, the director of wildlife, acknowledged that the department's efforts to keep land open to hunters have so far proved unsuccessful. The staff has learned how to work with foresters, hunters and landowners, he said, but, "We have not cracked the nut yet of people who want to post the land."

Vermont has long tried to encourage new young hunters with, for example, a Youth Deer Weekend in early November, when hunters younger than 16 may shoot a buck or a doe.

But in the immediate future, the state's most effective deer management strategy is likely to be changing the rules of Vermont's fall deer hunting season.

Current regulations allow a determined hunter to bag up to three deer, two of which can be bucks. Those kills can include a buck with two or more points on an antler during the 16-day rifle season, up to two of either sex during bow season, and a buck in December with a muzzleloader.

Hunters can also apply for an antlerless permit to shoot a doe during muzzleloader season. State biologists determine a set number of permits by region with population goals in mind and distribute them to hunters via lottery. In the areas with the most deer, antlerless permits often outnumber hunters, according to Fortin.

Fish & Wildlife is considering changes that would come into effect around 2022: allowing hunters of all ages to use the easier-to-shoot crossbow during bow season (currently, that's restricted to hunters older than 50), adding a muzzleloading season before the rifle season and increasing bag limits for bow hunters.

Commissioner Porter said he'd also like to expand and promote bow-and-arrow hunting in areas such as Chittenden County, where many homeowners have 10 to 20 acres of land suitable for hunting but not for shooting rifles.

He hopes to entice urban millennials to start hunting, touting the sport as a means "to get local, lean, hormone-free meat" and appealing to their environmentalism by teaching them the importance of deer control.

Hunters no longer have to go to a rural hunting camp to take down a deer; after all, Porter said, the joke among hunters has always been, "You drive by 20 deer in your front yard, and you drive to camp and don't see any deer for a week."

"We have a rare opportunity in Vermont with a group of Vermonters who don't come from hunting backgrounds," he said.

One strategy he said is not on the table: a regular rifle season on antlerless deer — females and yearling bucks. It's a management tool used by other states where deer are hunted. Vermont is the only one, in fact, without an antlerless rifle season. But the issue has a fraught political history in the Green Mountains.

When the deer population peaked in the 1960s, the state allowed the hunting of does to reduce the herd. Hunters pushed back with vehemence, arguing that the deer population wasn't too large and that shooting does would limit the future population and hunting opportunities.

An Eden Selectboard member, Ernest "Stub" Earle, led a campaign in 1969 to get landowners to post their land and allow access only to hunters who pledged not to shoot does. The acres of posted land across the state skyrocketed. Earle won a seat in the Vermont House the next year and later chaired the Fish and Game Committee.

At the largest Fish & Wildlife meeting of that period, Hall said, 1,300 hunters crowded into the Lamoille Union High School gym, red-faced and shouting angrily in protest of hunting does.

Since then, Scott added, the department has learned its lesson: Enacting hunting rules is "a much bigger social challenge than it is biological," he said.

The department invested heavily in the 1980s in training its staff to engage the public.

"We really had to change how we did business. It was no longer just science," Scott said. Ultimately, the change led to a more cooperative and educated public, he said.

These days, the public and the regulation-writing Fish & Wildlife Board, which is composed primarily of hunters, gives "huge deference" to biologists' recommendations, he said.

Nonetheless, the board and the department must control the size of the deer herd while also balancing the often-conflicting desires of landowners and hunters, and of those within the hunting community itself.

Foresters such as Nancy Patch, who works in Franklin and Grand Isle counties, believe the state needs a rifle season for does. Some hunters prefer a policy that ensures there will be plenty of deer to increase their chances of bagging one. Other hunters, according to Gallo of the Hunters Anglers Trappers Association, want management that results in fewer but larger deer.

Porter maintains that the existing strategy of varying the annual number of antlerless permits during muzzleloading season is sufficient to control the deer population in the majority of the state. In the areas where the herd continues to grow, the problem is not the hunters but the amount of posted land, he said.

In 2015, he lobbied the legislature to mandate that landowners who want the full tax break for keeping their land undeveloped be barred from posting their land.

Porter's effort fell flat. "The foresters and other landowners and legislators told me to get lost," he said.

What is clear is that the state will need to do something.

"Obviously, climate change is here to stay," Porter said. "Urban deer populations are here to stay. The decline in hunting numbers ... is likely here to stay, likely because of demographics of the state changing in terms of age. We're going to make sure we can manage the herd, taking those factors into account."

If the deer herd should continue to grow, Vermont can look to other states to understand the potentially drastic implications.

In Pennsylvania and parts of New York's Hudson Valley, heavy deer grazing means that forests may not regenerate at all — leaving no woods or just pine, said Tom Rawinski, a botanist for the U.S. Forest Service. With no trees replacing those that die, the forests "are living on borrowed time," he said.

Vermont doesn't yet face such acute overpopulation, Rawinski added, which allows the opportunity to head off more dire impacts. But, he added, "There are enough complaints across Vermont, especially from the forestry communities, that we need some serious action," he said.

Tapper, the Chittenden County forester, is doing what he can to control deer in the woods he owns in Bolton. He hunts with a rifle, has obtained a muzzleloader permit and is preparing to get a bow-hunting license. He aims to maximize the number of deer he can kill each year.

"I have literally become a hunter to deal with this issue," he said.

He invites local kids to his land on the youth hunting weekend in the hope that they'll kill some of the does that are eating his oak saplings.

When he explains his reasoning, some people raise their eyebrows. "People are like, 'You're approaching this in a really weird way,'" he said.

But Tapper remains determined.

"I'm doing population control," he responds. "I have to cull the herd on my land."

Comments (26)

Showing 1-25 of 26

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.