- File: Matthew Thorsen

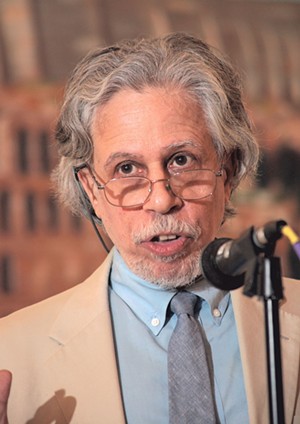

- Burlington Mayor Miro Weinberger

At 2 p.m. on November 20, a cadre of politicians flanked Burlington Mayor Miro Weinberger as he announced a $200 million redevelopment project in Vermont's largest city. They lauded the public-private partnership that would remake the sorry, single-story downtown mall into an urban complex of much-needed housing, retail shops and a hotel.

Roughly an hour earlier, two miles away, a small group of residents in Burlington's only mobile home park huddled outside, discussing a letter the mailman had just dropped off. It was from the park owner, notifying them that the prime real estate on which their houses sit was for sale.

The next day, Progressive City Councilor Jane Knodell commented on Facebook about what she called an "astonishing & disturbing contrast between the Mayor's 100% support for the redeveloper of BTV Town Center, and noncommittal remarks re preserving Farrington Mobile Home Park."

She was referring to a Burlington Free Press story, which stated that Weinberger had declined to comment on the situation at Farrington's because he hadn't been fully briefed.

The mayor responded swiftly, writing on Knodell's wall, "The City will work to protect these families, preserve Farrington's as an affordable housing resource, and improve the park's infrastructure conditions." And, he continued, "I am not blindly supporting the redeveloper, or at this point, any specific plan."

- Matthew Thorsen

- Steve Goodkind

Since then, Weinberger has taken care to show his support for the mobile home park residents, who are organizing to purchase the land as a cooperative.

But he hasn't managed to escape claims that he's cheerleading for development without due regard for the Queen City's most vulnerable residents.

In fact, that charge has become a central theme of the Burlington mayor's race. In his eagerness to grow Vermont's largest city, is Weinberger selling out the values that make it so famously livable?

Progressive Past

Democrat Weinberger has two challengers from the left, both of whom have been in Burlington since Bernie Sanders took over city hall in 1981. Progressive candidate Steve Goodkind was hired by the self-described socialist and eventually became director of public works — a job he held under five different mayors before retiring last year.

An engineer by trade, Goodkind is criticizing his most recent ex-boss for paving the way for developers to turn Burlington into an "enclave for the wealthy."

Long before Sanders was elected, leftist activist Greg Guma was advocating for rent control and other measures to combat gentrification in Burlington. Then he became editor of the Vermont Vanguard Press, which covered the Sanders administration and that of his Progressive successor, Peter Clavelle, until the alternative weekly folded in 1990.

- Matthew Thorsen

- Greg Guma

(Loyal Ploof, a Libertarian and repeat candidate for city offices, is also running for the city's top seat.)

Despite aggressively trying to distinguish himself from Goodkind, Guma is sounding the same alarm. At a sparsely attended press conference in the Big Heavy World radio studio last Friday, he slammed the mayor for trying to "turn the city into a resort town" and "promoting an anything-goes building boom."

Both Goodkind and Guma — who refer to the incumbent as "developer-in-chief" — are hoping to garner support among people who are alarmed by a visible increase in downtown development and plans to encourage more. Last spring, Seven Days documented seven projects under way, plus 11 more in the permitting process. Since then, one of the largest tracts of open land in the city has fallen into the hands of a developer who wants to build several hundred housing units there. Guma and Goodkind have decried the proposal and knocked the incumbent for failing to use his clout to stop the sale of the stunning lakeside acreage.

Weinberger didn't weigh in until a month after the announcement. When he did, the mayor adopted Clavelle's stance — that the city should promote mixed-income housing and a "generous amount" of open space on the site. As Clavelle's position shows, Burlington's Progressives have not been reflexively antidevelopment over the years.

- Matthew Thorsen

- Loyal Ploof

Beginning with Sanders, Burlington's city leaders have focused on creating perpetually affordable housing for low-income residents. The Queen City was one of the first municipalities in the country to adopt an inclusionary zoning ordinance, which ensures that 15 percent of units in every housing project remain affordable.

Sanders established Burlington's Community and Economic Development Office to implement his vision, according to Brian Pine, who worked there for 18 years, most recently as assistant director for housing. "Bernie had an unflagging commitment to the notion that government should be a tool for allocating resources and developing the environment to eliminate the great inequalities of wealth and power in our society, rather than to maintain and justify the status quo," Pine said in a speech at his going-away party last month.

According to Pine, that tradition carried on through the next three decades of predominantly Progressive rule. His city hall farewell bash, which had a distinct, end-of-an-era feel to it, attracted many former CEDO employees, including MC Michael Monte and his boss, Champlain Housing Trust director Brenda Torpy.

Also in the audience: CEDO's current director, Peter Owens, an urban designer and entrepreneur. He worked in California and the Upper Valley before Weinberger recruited him to jump-start economic growth in the Queen City.

Cleaning Up the Mess

Values aside, Weinberger did not inherit a walk in the park when he took office in 2012. He replaced Progressive Bob Kiss, who left the city's finances in shambles. Making matters worse: Citibank was suing Burlington for $33.5 million over the mismanagement of Burlington Telecom. Burlington's infrastructure was ailing, too — sidewalks, parking lots, municipal buildings and parks had fallen into disrepair.

During his first term, Weinberger brokered a settlement with Citibank that is expected to increase the city's overall credit rating. He eliminated deficits in the sewer and water funds. Credit ratings at the airport and the electrical department have improved on his watch. The city received a "clean" audit for 2014, and Weinberger announced that the city was in the black for the first time since 2009. Weinberger created a committee to examine the severely underfunded pension fund, though his administration has yet to propose a fix.

Weinberger has also overseen 61 city park upgrades, bike path renovations, sidewalk improvements and a face-lift for Waterfront Park.

Here's how he summarized his own achievements to the Democrats who recently endorsed him for a second term: "In short, the foundation of our city's greatness and prosperity was eroding. As we gather here today, Burlington faces a much different, and much brighter, future."

Attendees of the Burlington Business Association's annual summit at the Hilton last month embraced that pro-growth approach. The theme was housing, and a panel of developers, realtors and experts discussed how high housing costs strain the Queen City's economy.

"There is no boom," said Redstone Commercial Group developer Erik Hoekstra. His colleagues have attributed most of the new construction to rock-bottom interest rates and overall economic conditions rather than the man in charge.

- Matthew Thorsen

- Weinberger at the Burlington Town Center redevelopment announcement in November

During his turn at the podium that morning, Weinberger described a "renaissance" of downtowns across the country, on which Burlington has missed out. He spoke of young professionals leaving town and businesses failing to recruit employees. The culprit: a broken housing market that makes it nearly impossible for people to build downtown.

To illustrate the need for zoning changes and other reforms, the mayor recounted his own experience as a developer with the Hartland Group. Weinberger described the "harrowing" 10-year process of turning a "hated industrial warehouse" on Lakeview Terrace into a modern housing development called the Packard Lofts. Neighbors fought the project every step of the way, but Weinberger's group finally prevailed. "I hope it shows something about the persistence and stick-to-it-ness of this administration."

The mayor has already made some headway. For instance, he eliminated the costly "50/50 rule," which required developers to devote at least 50 percent of the square footage of downtown projects to commercial space.

But he's shooting for more sweeping changes during a second term.

At Weinberger's request, private consultants produced a report last May that analyzed the city's housing affordability crisis and suggested possible reforms. Based on that, CEDO developed a 17-point action plan. Although it hasn't been finalized, the administration is already laying the groundwork for a number of the recommendations. They include simplifying the building code, reducing zoning and permitting fees, and revaluating — and perhaps relaxing — historical preservation standards.

The impending housing plan also calls for eliminating the requirement that downtown developments include a minimum number of parking spaces. Weinberger, who tried to convince the council to do away with it last year, will continue to lobby for the change. The downtown already has plenty of parking spots, he's argued, and eliminating the rule would reduce the cost of building there.

That includes student housing. Weinberger supports the idea of housing more college kids in the city center as a way of preserving residential neighborhoods around it.

Goodkind has been especially critical of a proposal to build 1,500 units of student housing downtown.* His solution? Force the colleges to house all of their students on campus. College officials have previously dismissed similar proposals as untenable.

Meanwhile, the planning and zoning department has been introducing citizens and city officials to "form-based code." If adopted, it could radically transform how the city controls downtown development. As long as a building meets a standard set of requirements governing its physical appearance — height, setback, etc. — it would win approval. The new zoning code would leave much less up to the discretion of the development review board, and unlike the current ordinance, it wouldn't dictate which "uses" — commercial, industrial, residential — go where.

Both Guma and Goodkind caution that form-based code could bring on something else: fast-track development projects.

Go South

The mayor often points to planBTV — a multiyear community planning process for the downtown and waterfront that included input from more than 1,300 residents — as proof that his effort to promote investments in those parts of the city is consistent with what his constituents want.

Hoping to arrive at a similar consensus, Weinberger has launched another planBTV specifically for the South End, where a group of artists and business owners are concerned that possible zoning changes could price them out of their studios and work spaces, and sanitize the neighborhood's funky, gritty spirit.

In other words, they're worried about gentrification. Weinberger's challengers have capitalized on this fear, too. Guma dismissed the planning processes as a strategy to "engineer consent" for the administration's goals.

That's what it feels like to South End-based artist Genese Grill, who accuses city officials of "pretending that they are conducting an open community engagement process to find out what we want in the South End" when they "already have pretty clear directives and agendas."

CEDO director Owens has said the city has an obligation to at least consider rezoning the South End to allow for more housing. The consultants' report from last May strongly recommended it.

Bruce Seifer, a South End resident who worked in CEDO for three decades, said he believes the current administration is overly focused on increasing the city's housing stock. Building housing is more lucrative for developers, but Seifer warns that it could crowd out businesses in the South End.

Weinberger, who said he shares concerns about gentrification, stressed that no decisions have been made about whether the Enterprise Zone — a stretch of Pine Street that's become a hub for small businesses and artist studios — will be rezoned to allow for housing.

Guma and Goodkind have already come out against it.

Amey Radcliff has run her company, Gotham City Graphics, in the South End for the past two decades. She said Goodkind's philosophy — that Burlington has always developed "organically" and should continue that approach — resonates with her.

"We obviously have to do it in a smart way," Owens said of striking the right balance in the South End. "We have to do it in a way that respects the character and vibe of Burlington, but we can do that. That's fun stuff!"

The Price of Progress

Concerns about gentrification extend beyond the South End. After the mayor's announcement about the mall redevelopment, Progressive councilors immediately started asking for assurances that the project would include more than high-end apartments and luxury stores. It wasn't the first time they had publicly prodded Weinberger to consider the impacts of his policy proposals on low-income people.

"To me, that's the single biggest differentiating factor between Burlington Progressives and the mayor," Knodell said. For him, she said, "It's an afterthought."

Some affordable-housing advocates agree that Weinberger seems less attuned to the needs of Burlington's lowest-income residents. Neil Mickenberg, a retired Burlington lawyer who represented affordable housing organizations, said, "I think the mayor and the people in CEDO are thoughtful, and I think they are smart, but for reasons I don't understand, I don't think there has been as much emphasis on the needs of providing affordable housing for low-income people as there was under the Clavelle administration and the Sanders administration."

Amy Wright, a housing consultant and former CEDO employee, offered a similar assessment: "I just think the city was pretty remarkable at aggressively and proactively looking at affordable housing, and I'm not seeing that in the current administration, and I just want to make sure the protections stay strong."

During an interview last week, Weinberger insisted, "There's nothing about the policies we've put forward that would in any way step away from Burlington's proud, righteous history of developing affordable low-income housing, and, in fact, we are proposing to expand those resources."

He was referring to his housing plan's recommendations to restore funding to a city trust fund used to preserve housing for low-income residents, and to promote a "housing first" model for homeless people. The annual contribution to the trust fund would increase from $190,000 to $360,000.

The plan also proposes revisiting the inclusionary zoning requirement, noting that it can make projects "more difficult or unworkable" for developers.

Affordable housing advocates acknowledge that it could be time to tweak the city's 25-year-old ordinance, but they resent the way it's described in the housing plan — as a cost to developers rather than an effective tool for reducing social service costs elsewhere. And they emphasize that federal funding for affordable housing has been decimated during recent years, making it all the more important to preserve local support.

Both Goodkind and Guma say they'd do more to prioritize low-income residents. If he's elected mayor on March 3, Guma said, he would consider instituting a rent stabilization policy.

Weinberger acknowledged that his administration is paying more attention to people who aren't poor. "I think there has, to some degree, been a difference in emphasis on saying the city needs to be involved in more than worrying about just housing for the vulnerable residents," he said.

The mayor pointed out that the average Burlington resident spends 44 percent of his or her income on rent — proof that it's not just low-income people who are at risk of being priced out of the city. His housing plan also emphasizes this: "The lack of supply has profound negative consequences for Burlington. Instead of attracting young professionals eager to engage in the city's vibrant tech sector, for example, Burlington saw the percentage of such households actually fall by 10 percent between 2000 and 2012."

He cited what he called a "jarring" statistic: During a recent 12-year period, developers built a mere 18 market-rate housing units in Burlington.

"Out of 2,000 in the county," added Owens. "That meant that those other houses are out in farm fields having huge environmental impacts."

Growing Pains

Early in the campaign, Goodkind predicted, "I'll be the mayor's biggest fundraiser" — meaning his slow-growth talk would scare developers into ponying up for his opponent.

In truth, local developers were giving to Weinberger long before Goodkind threw his hat in the ring. Since he took office, the mayor has raised $93,000 from a donor list that includes many in the real estate business. Goodkind had raised $3,000 as of February 1, while Guma says he's collected roughly $5,500.

Both opponents are banking on what they say is a rising tide of discontent with Weinberger. Of course, if they're right, they are still competing to represent the dissatisfied ranks.

Both men attended a meeting at city hall last month that attracted hundreds who pledged to preserve the lakeside acreage behind Burlington College. Guma, who had not yet declared his candidacy, was on the panel. Looking professorial in a beige suit, with his glasses resting on the end of his nose, he delivered a speech that was part lecture, part call to arms. Wearing a sweater, work pants and his signature fur hat, Goodkind gave a campaign speech during the Q&A.

Weinberger, who had traveled to Washington, D.C., for a mayors' conference, was attending a fundraising event for his campaign while the meeting took place.

The mayor, who's adopted the campaign slogan "Moving Forward," has made it clear he thinks he's got the will of the people behind him. And he contends that when it comes to development, his past profession makes him best suited to "defend and promote the interest of Burlingtonians when we are working with other sophisticated financial parties."

Weinberger has been especially critical of Goodkind, suggesting that he managed the department of public works poorly and that his leadership would return Burlington to the "ways of the past."

But Weinberger is more hesitant to outright reject the concerns about development that Goodkind and Guma have identified.

At Weinberger's campaign office, Owens dismissed the effort to preserve the 27 acres behind Burlington College. "I think the rhetoric that you hear is quite honestly sort of old-school. It's a dated idea that development is bad and green is good. In fact, development is green!"

Looking slightly uncomfortable, the mayor fumbled with a pair of earbuds as Owens spoke. Then, not for the first time, Weinberger jumped in to soften his CEDO director's edict.

"I believe there is a lot of ambivalence in this community about whether we should grow or not, and I respect that and I understand that," he said. "I'm welcoming the debate because I think it's more complicated than just saying development is bad. I think we have to have a more nuanced conversation."

*Correction 2/12/15: Mayor Weinberger has proposed putting 1,500 units of student housing downtown. A larger figure originally reported in this story was from an earlier draft of a housing action plan.

Comments (5)

Showing 1-5 of 5

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.