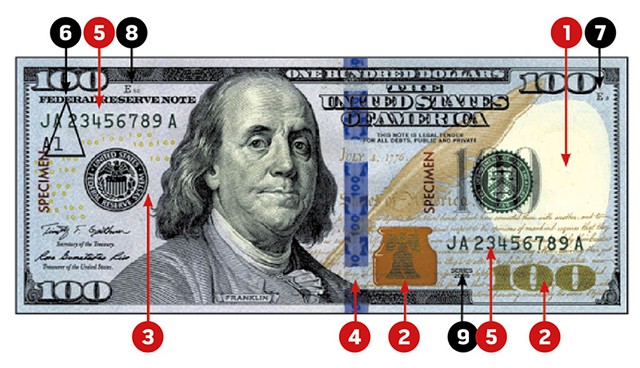

- KNOW YOUR MONEY

1. Watermark 2. Color-shifting ink 3. Security thread 4. 3D security ribbon 5. Serial numbers 6. Federal Reserve indicators 7. Note position and number 8. Face plate number 9. Series year 10. Back plate number (not shown)

On January 4 of this year, a Vermont State Police trooper stopped a vehicle on Interstate 89 in Royalton for a minor traffic offense. During the stop, police records indicate, the trooper discovered approximately $1,000 worth of counterfeit $20 bills in the vehicle. The driver, a 24-year-old tattoo artist from Brockton, Mass., was taken into custody for allegedly counterfeiting U.S. currency.

Although the federal offense carries a potential penalty of up to $250,000 in fines and 20 years in prison, the U.S. Secret Service, which investigates such cases, declined to prosecute, citing the relatively small quantity of phony bills seized. As state trooper Rich Slusser, who made the arrest, explains, Vermont statute only considers counterfeiting a crime if there's "intent to injure or defraud." As Slusser puts it, "It's not against the law to just have it."

In the age of global email phishing scams, online identity fraud, and the wholesale hacking and theft of millions of credit card numbers from national databases, there's something almost quaint about the crime of physically printing money at home. But cases like this aren't as rare as one might assume. While the rapid proliferation of online transactions has made it easier and faster for thieves to steal funds electronically, law enforcement agents charged with investigating financial crimes say that advances in digital technology have also made it much easier for forgers to get away with making their own dough.

And, while anecdotal evidence shows scant public awareness of counterfeiting in Vermont, the state isn't immune.

In August 2013, four men from Brooklyn, N.Y., were sentenced in U.S. District Court in Burlington for bleaching genuine $5 bills and digitally printing them with the image of a $100 bill. The men tried to pass their bogus Benjamins at convenience stores and gas stations on Shelburne Road in South Burlington. In a press release coinciding with their conviction, the U.S. attorney's office in Burlington described their criminal enterprise as a "counterfeiting caper."

While that word may conjure up images of A-list actors clowning around in Ocean's Eleven, the Secret Service takes the forgery of Federal Reserve notes very seriously. In fact, preventing it was the agency's original raison d'être. The Secret Service was created immediately after the Civil War to combat what had become a counterfeiting epidemic. It wasn't until the assassination of President William McKinley in 1901 that the agency assumed its better-known duty of protecting presidents, other federal officials and visiting foreign dignitaries.

Vermont has a long history of printing and engraving its own money, legit and otherwise. The American Revolution created a shortage of metal, and paper money was so likely to be counterfeit that many Vermonters eschewed it. For many years after the war, most Vermont business transactions were conducted using foreign coinage, generally that of England or Spain, according to Marjorie Strong, an assistant librarian at the Vermont Historical Society. For daily transactions, many Vermonters simply bartered. In fact, before it joined the Union in 1791, the Vermont Republic recognized cattle, beef, pork, sheep, wheat, rye and corn as legal tender. Why? Such commodities had their own intrinsic value, unlike bills that could be faked.

These days, Vermont's state and local police don't encounter counterfeit cash all that often. A state police representative says no one on staff has the expertise to work on such cases, which are generally turned over to the Secret Service office in Burlington. The Vermont Department of Financial Regulation doesn't even track the occurrence of counterfeiting.

In large urban centers such as New York City, counterfeiters routinely try to pass off phony $20, $50 and $100 bills in crowded, dimly lit bars and nightclubs. In Vermont, by contrast, bartenders aren't seeing many dodgy dollars. Bill Goggins, head of the education, licensing and enforcement division at the Department of Liquor Control, says that in his 25 years there, "I have never encountered a licensee who inadvertently took in counterfeit money."

Local bank tellers aren't finding many counterfeits, either. Christopher D'Elia, president and treasurer of the Vermont Bankers Association, says he can't remember the last time counterfeit cash posed a serious concern for the 20 banks doing business in the state. Likewise, Joe Bergeron, president of the Association of Vermont Credit Unions, says a survey of his 21 member institutions, conducted just a week ago, revealed that the incidence of counterfeit currency there is "virtually nonexistent."

Yet, while crooked cash may not appear in the first places one expects, it still turns up in the Green Mountain State with some frequency. Holly Fraumeni, resident agent in charge of the Manchester, N.H., office of the Secret Service, reports that, in 2015, criminals passed 913 treasury notes in Vermont with a total face value of $38,197. That figure was down from the previous year, when crooks spent or attempted to cash $44,668 worth of bogus bills in Vermont.

The problem is worse across the river in New Hampshire, Fraumeni adds, where 3,251 forged banknotes were passed in 2015, with a total face value of $215,992 — up from the previous year's $206,224.

Why the big disparity between Vermont and the Granite State? Fraumeni, who's worked for the Secret Service in various capacities for more than 25 years, suggests that New Hampshire's proximity to large population centers, and the routes that serve them, could be responsible. A common ploy, she explains, is for crooks to travel major highways with counterfeit bills, then try to spend or cash them along the way in malls, gas stations, rest stops and convenience stores, where busy or untrained clerks may not recognize the fakes.

Other people who handle money may actually be over-vigilant. Fraumeni says her office occasionally gets calls from young bank tellers who are unaccustomed to receiving banknotes minted before the 1990s. They may suspect forgery when someone turns in a crisp bill that's been sitting in a drawer for decades, such as a silver certificate from the 1920s or '30s. Fraumeni can pronounce those bills authentic — and calls them "beautiful pieces of art."

Where does New England's illegal tender tend to originate? For that answer, Fraumeni passes the buck to Robert Hoback, a 16-year veteran of the Secret Service who now works in the agency's Washington, D.C., headquarters. While Hoback can't speak specifically about New England's counterfeit supply, he points out that it represents only a drop in the bucket of the $146.5 million in counterfeit currency that was passed and seized globally in fiscal year 2014.

Of the $85.4 million in counterfeit currency that was seized within the United States that year, he reports, 61 percent was manufactured using digital printing technologies. The remaining 39 percent was produced using traditional or offset printing technologies, "like the kind used to print newspapers."

In the past decade, Hoback elaborates, the Secret Service has seen a big shift away from the relatively small number of high-skilled forgers who use traditional printing methods to produce large quantities of quality counterfeit notes — typically $50 and $100 bills. These days, most phony bills are made by unskilled counterfeiters using off-the-shelf digital printers. Contrary to what many might assume, Hoback says, most domestic counterfeit operations aren't linked to organized crime. They're more likely to be "an 18-year-old in his basement or garage just printing them off an ink-jet printer."

High-quality fakes are another story, Hoback adds, and typically originate outside the U.S. In May 2014, for example, large quantities of counterfeits began turning up in the Boston area; they were so convincing that even trained eyes had trouble detecting them.

Investigators from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police spent four years tracing those counterfeits back to a Canadian forger named Frank Bourassa, who used a four-color Heidelberg offset printer and the same recipe for the rag paper — 75 percent cotton and 25 percent linen — that the U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing uses for its notes. In an October 2014 story in GQ titled "The Great Paper Caper," by Wells Tower, Bourassa claims to have printed as much as $250 million before getting nabbed.

In recent years, Hoback notes, the Secret Service has opened offices in Colombia and Peru to crack down on organized counterfeit operations there. In 2014, the agency's Project South America seized $29.2 million, arrested 75 individuals and suppressed 12 counterfeit operations in those countries.

Outside the U.S., Hoback says, the $100 bill is both the most circulated and the most commonly forged. Domestically, the $20 bill is most frequently faked. And, notwithstanding Bourassa's seemingly genuine articles, Hoback says that most counterfeit bills aren't hard to discover, with the best tip-off being not their appearance but their texture.

The predominant problem, then, isn't the counterfeiters' expertise but the failure of those who receive the bills to notice. "Monopoly money passes, believe it or not," Hoback says. "And those big bills that say, 'For motion picture use only'? Those pass, too, all the time," he adds. "So, it all boils down to the store clerks in these places being educated a little more ... and just paying a little more attention to the money they're receiving."

That's advice you can take to the bank.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.